Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to 549.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

from Wikipedia

| Years |

|---|

| Millennium |

| 1st millennium |

| Centuries |

| Decades |

| Years |

| 549 by topic |

|---|

| Leaders |

| Categories |

| Gregorian calendar | 549 DXLIX |

| Ab urbe condita | 1302 |

| Assyrian calendar | 5299 |

| Balinese saka calendar | 470–471 |

| Bengali calendar | −45 – −44 |

| Berber calendar | 1499 |

| Buddhist calendar | 1093 |

| Burmese calendar | −89 |

| Byzantine calendar | 6057–6058 |

| Chinese calendar | 戊辰年 (Earth Dragon) 3246 or 3039 — to — 己巳年 (Earth Snake) 3247 or 3040 |

| Coptic calendar | 265–266 |

| Discordian calendar | 1715 |

| Ethiopian calendar | 541–542 |

| Hebrew calendar | 4309–4310 |

| Hindu calendars | |

| - Vikram Samvat | 605–606 |

| - Shaka Samvat | 470–471 |

| - Kali Yuga | 3649–3650 |

| Holocene calendar | 10549 |

| Iranian calendar | 73 BP – 72 BP |

| Islamic calendar | 75 BH – 74 BH |

| Javanese calendar | 437–438 |

| Julian calendar | 549 DXLIX |

| Korean calendar | 2882 |

| Minguo calendar | 1363 before ROC 民前1363年 |

| Nanakshahi calendar | −919 |

| Seleucid era | 860/861 AG |

| Thai solar calendar | 1091–1092 |

| Tibetan calendar | ས་ཕོ་འབྲུག་ལོ་ (male Earth-Dragon) 675 or 294 or −478 — to — ས་མོ་སྦྲུལ་ལོ་ (female Earth-Snake) 676 or 295 or −477 |

Year 549 (DXLIX) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 549 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Events

[edit]By place

[edit]Byzantine Empire

[edit]- Siege of Rome: The Ostrogoths under Totila besiege Rome for the third time, after Belisarius has returned to Constantinople. He offers a peace agreement, but this is rejected by Emperor Justinian I.

- Totila conquers the city of Perugia (Central Italy) and stations a Gothic garrison. He takes bishop Herculanus prisoner, and orders him to be completely flayed. The Ostrogoth soldier asked to perform this gruesome execution shows pity, and decapitates Herculanus before the skin on every part of his body is removed.[1]

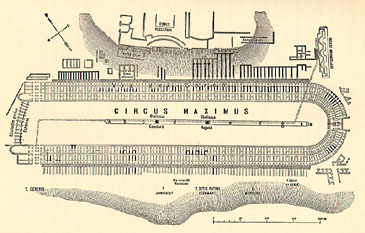

- In the Circus Maximus, first and largest circus in Rome, the last chariot races are held.[2]

Europe

[edit]- January - Battle of Ciiil Conaire, Ireland: Ailill Inbanda and his brother are defeated and killed.[3]

- Agila I succeeds Theudigisel as king of the Visigoths, after he is murdered by a group of conspirators during a banquet in Seville.[4]

Persia

[edit]- Spring – Lazic War: The Byzantine army under Bessas combines forces with King Gubazes II, and defeats the Persians in Lazica (modern Georgia) in a surprise attack. The survivors retreat into Caucasian Iberia.[5]

- The Romans unsuccessfully besiege Petra, Lazica.

Asia

[edit]- Jianwen Di succeeds his father Wu Di as emperor of the Liang Dynasty (China).

By topic

[edit]Religion

[edit]- c. 549–564 – Transfiguration of Christ, mosaic in the apse, Church of the Virgin, Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt, is made.

- Fifth Council of Orléans: Nine archbishops and forty-one bishops pronounce an anathema against the errors of Nestorius and Eutyches.[6]

- Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna consecrates the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe.

- The Roman Catholic Diocese of Ossory (which still exists) is founded in Ireland.

Births

[edit]Deaths

[edit]- January – Ailill Inbanda, king of Connacht (Ireland) (killed in battle)[3]

- February 16 – Zhu Yi, official of the Liang dynasty (b. 483)

- December 12 – Finnian of Clonard, Irish monastic saint (b. 470)

- exact date unknown

- Ciarán of Clonmacnoise, Irish monastic saint[7]

- Gao Cheng, official and regent of Eastern Wei (b. 521)[8]

- Herculanus, bishop of Perugia[9]

- Theudigisel, king of the Visigoths (assassinated)[10]

- Túathal Máelgarb, king of Tara (Ireland)[11]

- Wu Di, emperor of the Liang dynasty (b. 464)[12]

- Xiao Zhengde, prince of the Liang dynasty[13]

- Xu Zhaopei, princess of the Liang dynasty[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Saint of the Day, November 7: Herculanus of Perugia, archived by Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Donnell, James (2008). The Ruin of the Roman Empire. New York: HarperCollins. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-06-078737-0.

- ^ a b T. M. Charles-Edwards (2006). The Chronicle of Ireland: Introduction, text. Liverpool University Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-85323-959-8.

- ^ Isidore of Seville, Historia de regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum, chapter 44. Translation by Guido Donini and Gordon B. Ford, Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi, second revised edition (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1970), p.21

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 381–382

- ^ Council of Orléans Archived September 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ P.W. Joyce (March 22, 2018). A Concise History of Ireland. Charles River Editors. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-61430-701-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. September 22, 2014. p. 1697. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- ^ Anna Welch (October 15, 2015). Liturgy, Books and Franciscan Identity in Medieval Umbria. BRILL. p. 188. ISBN 978-90-04-30467-3.

- ^ Kenneth Baxter Wolf (1999). Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain. Liverpool University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-85323-554-5.

- ^ Pádraig Ó Riain (1985). Corpus genealogiarum sanctorum Hiberniae. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 9780901282804.

- ^ Peter Connolly; John Gillingham; John Lazenby (May 13, 2016). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-135-93674-7.

- ^ Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. September 22, 2014. p. 1552. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- ^ Wanton Women in Late-Imperial Chinese Literature: Models, Genres, Subversions and Traditions. BRILL. March 27, 2017. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-04-34062-6.

- Bibliography

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

from Grokipedia

Year 549 (DXLIX) was a common year of the Julian calendar, marked principally by military developments in the Gothic War between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantine Empire. Ostrogothic king Totila, having previously lost Rome to Byzantine forces under Belisarius in 547, laid siege to the city once more and retook it in late 549 through betrayal by some of the defenders, who opened the gates to his army.[1][2] To restore normalcy and bolster morale, Totila organized chariot races at the Circus Maximus, the last documented such event at the venue after nearly a millennium of use.[3][4] Concurrently, the Byzantine Empire initiated the Lazic War against the Sassanid Persians by besieging the fortress of Petra in Lazica, a conflict that would endure until 556.[5] In Iberia, Visigothic king Theudigisel was assassinated and succeeded by Agila amid internal strife.[6]