Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Procopius

View on WikipediaProcopius of Caesarea (/proʊˈkoʊpiəs/;[1] Ancient Greek: Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς Prokópios ho Kaisareús; Latin: Procopius Caesariensis; c. 500 – 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima.[2][3] Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Emperor Justinian's wars, Procopius became the principal historian of the 6th century, writing the History of the Wars, the Buildings, and the infamous Secret History.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Apart from his own writings, the main source for Procopius's life is an entry in the Suda,[4] a Byzantine Greek encyclopaedia written sometime after 975 which (based on older sources) discusses his early life. He was a native of Caesarea in the province of Palaestina Prima.[5] He would have received a conventional upper-class education in the Greek classics and rhetoric,[6] perhaps at the famous school at Gaza.[7] He may have attended law school, possibly at Berytus (present-day Beirut) or Constantinople (now Istanbul),[8][a] and became a lawyer (rhetor).[4] He evidently knew Latin, as was natural for a man with legal training.[b]

Career

[edit]In 527, the first year of the reign of the emperor Justinian I, Procopius became the legal adviser (adsessor) for Belisarius, a Roman general whom Justinian made his chief military commander in a great attempt to restore control over the lost western provinces of the empire.[c]

Procopius was with Belisarius on the eastern front until the latter was defeated at the Battle of Callinicum in 531[12] and recalled to Constantinople.[13] Procopius witnessed the Nika riots of January, 532, which Belisarius and his fellow general Mundus repressed with a massacre in the Hippodrome there.[14] In 533, he accompanied Belisarius on his victorious expedition against the Vandal kingdom in North Africa, took part in the capture of Carthage, and remained in Africa with Belisarius's successor Solomon the Eunuch when Belisarius returned east to the capital. Procopius recorded a few of the extreme weather events of 535–536, although these were presented as a backdrop to Byzantine military activities, such as a mutiny in and around Carthage.[15][d] He rejoined Belisarius for his campaign against the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy and experienced the Gothic siege of Rome that lasted a year and nine days, ending in mid-March 538. He witnessed Belisarius's entry into the Gothic capital, Ravenna, in 540. Both the Wars[16] and the Secret History suggest that his relationship with Belisarius cooled thereafter. Perhaps he accompanied the general once more to the Persian front in 542. When Belisarius was sent back to Italy in 544 to cope with a renewal of the war with the Goths, now led by the able king Totila, Procopius appears to have no longer been on Belisarius's staff.[citation needed]

As magister militum, Belisarius was an "illustrious man" (Latin: vir illustris; Ancient Greek: ἰλλούστριος, illoústrios); being his adsessor, Procopius must therefore have had at least the rank of a "visible man" (vir spectabilis). He thus belonged to the mid-ranking group of the senatorial order (ordo senatorius). However, the Suda, which is usually well-informed in such matters, also describes Procopius himself as one of the illustres. Should this information be correct, Procopius would have had a seat in Constantinople's senate, which was restricted to the illustres under Justinian.

Death

[edit]It is not certain when Procopius died. Many historians—including Howard-Johnson, Cameron, and Geoffrey Greatrex—date his death to 554, but there was an urban prefect of Constantinople (praefectus urbi Constantinopolitanae) who was called Procopius in 562. In that year, Belisarius was implicated in a conspiracy and was brought before this urban prefect.[17]

Writings

[edit]

The writings of Procopius are the primary source of information for the rule of the emperor Justinian I. Procopius was the author of a history in eight books on the wars prosecuted by Justinian, a panegyric on the emperor's public works projects throughout the empire, and a book known as the Secret History that claims to report the scandals that Procopius could not include in his officially sanctioned history for fear of angering the emperor, his wife, Belisarius, and the general's wife Antonia.

History of the Wars

[edit]Procopius's Wars or History of the Wars (Ancient Greek: Ὑπὲρ τῶν Πολέμων Λόγοι, Hypèr tōn Polémon Lógoi, "Words on the Wars"; Latin: De Bellis, "On the Wars") is his most important work, although less well known than the Secret History.[18] The first seven books seem to have been largely completed by 545 and may have been published as a set. They were, however, updated to mid-century before publication, with the latest mentioned event occurring in early 551. The eighth and final book brought the history to 553.

The first two books—often known as The Persian War (Latin: De Bello Persico)—deal with the conflict between the Romans and Sassanid Persia in Mesopotamia, Syria, Armenia, Lazica, and Iberia (present-day Georgia).[19] It details the campaigns of the Sassanid shah Kavadh I, the 532 'Nika' revolt, the war by Kavadh's successor Khosrau I in 540, his destruction of Antioch and deportation of its inhabitants to Mesopotamia, and the great plague that devastated the empire from 542. The Persian War also covers the early career of Procopius's patron Belisarius in some detail.[20]

The Wars’ next two books—known as The Vandal War or Vandalic War (Latin: De Bello Vandalico)—cover Belisarius's successful campaign against the Vandal kingdom that had occupied Rome's provinces in northwest Africa for the last century.

The final four books—known as The Gothic War (Latin: De Bello Gothico)—cover the Italian campaigns by Belisarius and others against the Ostrogoths. Procopius includes accounts of the 1st and 2nd sieges of Naples and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sieges of Rome. He also includes an account of the rise of the Franks (see Arborychoi). The last book describes the eunuch Narses's successful conclusion of the Italian campaign and includes some coverage of campaigns along the empire's eastern borders as well.

The War histories contain various longer excursions on different topics. These serve both literary and thematic purposes by providing the necessary background information as well as contextualising the acts of war described on different levels.[21][22] The Wars proved influential on later Byzantine historiography.[23] In the 570s Agathias wrote Histories, a continuation of Procopius's work in a similar style.

Secret History

[edit]

Procopius's now famous Anecdota, also known as Secret History (Ancient Greek: Ἀπόκρυφη Ἱστορία, Apókryphe Historía; Latin: Historia Arcana), was discovered centuries later at the Vatican Library in Rome[24] and published in Lyon by Niccolò Alamanni in 1623. Its existence was already known from the Suda, which referred to it as Procopius's "unpublished works" containing "comedy" and "invective" of Justinian, Theodora, Belisarius and Antonina. The Secret History covers roughly the same years as the first seven books of The History of the Wars and appears to have been written after they were published. Current consensus generally dates it to 550, or less commonly 558. Since no author seems to have been aware of this work for centuries, even though Procopius was widely read and quoted, the Secret History appears to have remained unknown for several generations. How and when the text was published is unknown.

In the eyes of many scholars, the Secret History reveals an author who had become deeply disillusioned with Emperor Justinian, his wife Theodora, the general Belisarius, and his wife Antonina. The work claims to expose the secret springs of their public actions, as well as the private lives of the emperor and his entourage. In recent years, however, other scholars have warned against confusing the account in the Secret History with Procopius' actual opinion.[25] Justinian is portrayed as cruel, venal, prodigal, and incompetent. In one passage, it is even claimed that he was possessed by demonic spirits or was himself a demon lord:

And some of those who have been with Justinian at the palace late at night, men who were pure of spirit, have thought they saw a strange demoniac form taking his place. One man said that the Emperor suddenly rose from his throne and walked about, and indeed he was never wont to remain sitting for long, and immediately Justinian's head vanished, while the rest of his body seemed to ebb and flow; whereat the beholder stood aghast and fearful, wondering if his eyes were deceiving him. But presently he perceived the vanished head filling out and joining the body again as strangely as it had left it.[26]

Similarly, the Theodora of the Secret History is a garish portrait of vulgarity and insatiable lust juxtaposed with cold-blooded self-interest, shrewishness, and envious and fearful mean-spiritedness. Throughout the Secret History, Procopius both reminds us of Theodora's humble origins and criticizes her lack of moral virtue, reputation, and education. [27] Among the more titillating (and dubious) revelations in the Secret History is Procopius's account of Theodora's thespian accomplishments:

Often, even in the theatre, in the sight of all the people, she removed her costume and stood nude in their midst, except for a girdle about the groin: not that she was abashed at revealing that, too, to the audience, but because there was a law against appearing altogether naked on the stage, without at least this much of a fig-leaf. Covered thus with a ribbon, she would sink to the stage floor and recline on her back. Slaves to whom the duty was entrusted would then scatter grains of barley from above into the calyx of this passion flower, whence geese, trained for the purpose, would next pick the grains one by one with their bills and eat.[28]

Justinian and Theodora are portrayed as the antithesis of good rulers, with each representing the opposite side of the emotional spectrum. Justinian was approachable and kindly, even while ordering property confiscations or people's destruction. Conversely, Theodora was described as irrational and driven by her anger, often by minor affronts.[29]

Furthermore, Secret History portrays Belisarius as a weak man completely emasculated by his wife, Antonina, who is portrayed in very similar terms to Theodora. They are both said to be former actresses and close friends. Procopius claimed Antonina worked as an agent for Theodora against Belisarius, and had an ongoing affair with Belisarius' godson, Theodosius.

The Buildings

[edit]

The Buildings (Ancient Greek: Περὶ Κτισμάτων, Perì Ktismáton; Latin: De Aedificiis, "On Buildings") is a panegyric on Justinian's public works projects throughout the empire.[30] The first book may date to before the collapse of the first dome of Hagia Sophia in 557, but some scholars think that it is possible that the work postdates the building of the bridge over the Sangarius in the late 550s.[31] Historians consider Buildings to be an incomplete work due to evidence of the surviving version being a draft with two possible redactions.[30][32]

Buildings was likely written at Justinian's behest, and it is doubtful that its sentiments expressed are sincere. It tells us nothing further about Belisarius, and it takes a sharply different attitude towards Justinian. He is presented as an idealised Christian emperor who built churches for the glory of God and defenses for the safety of his subjects. He is depicted showing particular concern for the water supply, building new aqueducts and restoring those that had fallen into disuse. Theodora, who was dead when this panegyric was written, is mentioned only briefly, but Procopius's praise of her beauty is fulsome.

Due to the panegyrical nature of Procopius's Buildings, historians have discovered several discrepancies between claims made by Procopius and accounts in other primary sources. A prime example is Procopius's starting the reign of Justinian in 518, which was the start of the reign of his uncle and predecessor Justin I. By treating the uncle's reign as part of his nephew's, Procopius was able to credit Justinian with buildings erected or begun under Justin's administration. Such works include renovation of the walls of Edessa after its 525 flood and consecration of several churches in the region. Similarly, Procopius falsely credits Justinian for the extensive refortification of the cities of Tomis and Histria in Scythia Minor. This had been carried out under Anastasius I, who reigned before Justin.[33]

Interpretations of Procopius' works

[edit]Procopius is generally believed to be aligned with the senatorial ranks that disagreed with Justinian's tax policy (Secret History 12.12-14).[34][35] Over time, Procopius' initial optimism may have been replaced by his disillusionment with Belisarius and increasing dislike of Justinian.[36]

Henning Börm has argued that Procopius prepared the Secret History as an exaggerated document out of fear that a conspiracy might overthrow Justinian's regime, which—as a kind of court historian—might be reckoned to include him. The unpublished manuscript would then have been an insurance that could be offered to the new ruler as a way to avoid punishment. If this hypothesis is correct, the Secret History would not be proof that Procopius hated Justinian or Theodora.[37]

Anthony Kaldellis suggests that the Secret History tells the dangers of "the rule of women". For Procopius, it was not that women could not lead an empire, but only women demonstrating masculine virtues could.[38] According to Averil Cameron, the definition of "feminine" behavior in the sixth century would be described as "intriguing" and "interfering".[39] At his core, Procopius wanted to preserve the social order.[e]

Averil Cameron makes a case that all of his works form a continuous, unified discourse, rather than being contradictory to one another.[41] In her view, Procopius was a better reporter than a historian, whose strength lay in descriptions rather than analyses.[42] She argues that his vision is too black-and-white and remains almost silent on theological and ecclesiastical debates.[43] However, Shaun Tougher notes Procopius' intention to write an ecclesiastical history, which may have provided a more holistic picture of his time, and argues that Procopius should not be assessed as negatively.[44]

Style

[edit]Procopius belongs to the school of late antique historians who continued the traditions of the Second Sophistic. They wrote in Attic Greek. Their models were Herodotus, Polybius and in particular Thucydides. Their subject matter was secular history. They avoided vocabulary unknown to Attic Greek and inserted an explanation when they had to use contemporary words. Thus Procopius includes glosses of monks ("the most temperate of Christians") and churches (as equivalent to a "temple" or "shrine"), since monasticism was unknown to the ancient Athenians and their ekklesía had been a popular assembly.[45]

The secular historians eschewed the history of the Christian church. Ecclesiastical history was left to a separate genre after Eusebius. Cameron has argued that Procopius's works reflect the tensions between the classical and Christian models of history in 6th-century Constantinople. This has been supported by Whitby's analysis of Procopius's depiction of the capital and its cathedral in comparison to contemporary pagan panegyrics.[46] Procopius can be seen as depicting Justinian as essentially God's vicegerent, making the case for buildings being a primarily religious panegyric.[47] Procopius indicates that he planned to write an ecclesiastical history himself[48] and, if he had, he would probably have followed the rules of that genre. As far as known, however, such an ecclesiastical history was never written.

Some historians have criticized Propocius's description of some barbarians, for example, he dehumanized the unfamiliar Moors as "not even properly human". This was, however, inline with Byzantine ethnographic practice in late antiquity.[49]

Legacy

[edit]A number of historical novels based on Procopius's works (along with other sources) have been written. Count Belisarius was written by poet and novelist Robert Graves in 1938. Procopius himself appears as a minor character in Felix Dahn's A Struggle for Rome and in L. Sprague de Camp's alternate history novel Lest Darkness Fall. The novel's main character, archaeologist Martin Padway, derives most of his knowledge of historical events from the Secret History.[50]

The narrator in Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick cites Procopius's description of a captured sea monster as evidence of the narrative's feasibility.[51] A fictionalized version of Procopius, named Pertennius, appears in the fantasy novelist Guy Gavriel Kay's duology The Sarantine Mosaic.

List of selected works

[edit]- J. Haury, ed. (1962–1964) [1905]. Procopii Caesariensis opera omnia (in Greek). Revised by G. Wirth. Leipzig: Teubner.

4 volumes

- Dewing, H. B., ed. (1914–1940). Procopius. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press and Hutchinson. Seven volumes, Greek text and English translation.

- Downey, G.; Dewing, Henry B., eds. (1940). Buildings of Justinian. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Procopius: The Secret History. Penguin Classics. Translated by Williamson, G. A. Revised by Peter Sarris. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 2007 [1966]. ISBN 978-0140455281.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) English translation of the Anecdota. - Prokopios: The Secret History. Translated by Anthony Kaldellis. Indianapolis: Hackett. 2010. ISBN 978-1603841801.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For an alternative reading of Procopius as a trained engineer, see Howard-Johnson.[9]

- ^ Procopius uses and translates a number of Latin words in his Wars. Börm suggests a possible acquaintance with Vergil and Sallust.[10]

- ^ Procopius speaks of becoming Belisarius's advisor (symboulos) in that year.[11]

- ^ Before modern times, European and Mediterranean historians, as far as weather is concerned, typically recorded only the extreme or major weather events for a year or a multi-year period, preferring to focus on the human activities of policymakers and warriors instead.

- ^ Henning Börm described this social order as a "social hierarchy: people stood over animals, freemen stood over slaves, men stood over eunuchs, and men stood over women. Whenever Procopius denounces the alleged breach of these rules, he is following the rules of historiography."[40]

References

[edit]- ^ "Procopius". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Morcillo, Jesús Muñoz; Robertson-von Trotha, Caroline Y. (30 November 2020). Genealogy of Popular Science: From Ancient Ecphrasis to Virtual Reality. Transcript. p. 332. ISBN 978-3-8394-4835-9.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther, eds. (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 1214–1215. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

Procopius: Greek historian, born in *Caesarea (2) in Palestine c. AD 500.

- ^ a b Suda pi.2479. See under 'Procopius' on Suda On Line.

- ^ Procopius, Wars of Justinian I.1.1; Suda pi.2479. See under 'Procopius' on Suda On Line.

- ^ Cameron 1985, p. 7.

- ^ Evans 1972, p. 31.

- ^ Cameron 1985, p. 6.

- ^ Howard-Johnson, James: 'The Education and Expertise of Procopius'; in Antiquité Tardive 10 (2002), 19–30.

- ^ Börm 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Procopius, Wars, 1.12.24.

- ^ Wars, I.18.1-56.

- ^ Wars, I.21.2.

- ^ Wars, I.24.1-58.

- ^ 1.

- ^ Wars, VIII.

- ^ "Procopio di Cesarea". www.summagallicana.it. Retrieved 9 July 2025.

- ^ Procopius (1914). "Procopius, de Bellis. H.B. (Henry Bronson) Dewing, Ed. [First section:] Procop. Pers. 1.1". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

[Opening line in Greek] Προκόπιος Καισαρεὺς τοὺς πολέμους ξυνέγραψεν οὓς Ἰουστινιανὸς ὁ Ῥωμαίων βασιλεὺς πρὸς βαρβάρους διήνεγκε τούς τε ἑῴους καὶ ἑσπερίους,... Translation: Procopius from Caesarea wrote the history of the wars of Roman Emperor Justinianus against the barbarians of the East and of the West..

. Greek text edition by Henry Bronson Dewing, 1914. - ^ Börm 2007.

- ^ Cf. Henning Börm: Procopius and the East. In: Mischa Meier, Federico Montinaro (eds.): A Companion to Procopius of Caesarea. Boston 2022, pp. 310 ff.

- ^ Riemenschneider 2024.

- ^ Ziebuhr 2024.

- ^ Cresci 2001.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Daniel (26 December 2010). "God's Librarians". The New Yorker.

- ^ Börm 2015, pp. 326–338; Stewart 2020, pp. 31–67; Brodka 2022, pp. 71–76.

- ^ Procopius, Secret History 12.20–22, trans. Atwater.

- ^ Grau, Sergi & Febrer, Oriol. (2020). Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns. Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 113. 769-788. 10.1515/bz-2020-0034.

- ^ Procopius Secret History 9.20–21, trans. Atwater.

- ^ Georgiou, Andriani (2019), Constantinou, Stavroula; Meyer, Mati (eds.), "Empresses in Byzantine Society: Justifiably Angry or Simply Angry?", Emotions and Gender in Byzantine Culture, New Approaches to Byzantine History and Culture, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 123–126, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96038-8_5, ISBN 978-3-319-96037-1, S2CID 149788509

- ^ a b Downey, Glanville: "The Composition of Procopius, De Aedificiis", in Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 78: pp. 171–183; abstract from JSTOR.

- ^ Whitby, Michael: "Procopian Polemics: a review of A. Kaldellis Procopius of Caesarea. Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity", in The Classical Review 55 (2006), pp. 648ff.

- ^ Cameron 1985.

- ^ Croke, Brian and James Crow: "Procopius and Dara", in The Journal of Roman Studies 73 (1983), 143–159.

- ^ Grau, Sergi; Febrer, Oriol (1 August 2020). "Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 113 (3): 779–780. doi:10.1515/bz-2020-0034. ISSN 1868-9027. S2CID 222004516.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora. University of Texas Press. pp. x. doi:10.7560/721050. ISBN 978-0-292-79895-3.

- ^ Tougher 1996, p. 206.

- ^ Cf. Börm (2015).

- ^ Kaldellis 2004, pp. 144–147.

- ^ Cameron 1985, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Stewart 2020, p. 173.

- ^ Tougher 1996, p. 205.

- ^ Cameron 1985, pp. 241.

- ^ Cameron 1985, pp. 227–229.

- ^ Tougher 1996, pp. 206, 209.

- ^ Wars, 2.9.14 and 1.7.22.

- ^ Buildings, Book I.

- ^ Whitby, Mary: "Procopius' Buildings Book I: A Panegyrical Perspective", in Antiquité Tardive 8 (2000), 45–57.

- ^ Secret History, 26.18.

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2013). Ethnography after antiquity : foreign lands and peoples in Byzantine literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8122-0840-5. OCLC 859162344.

- ^ de Camp, L. Sprague (1949). Lest Darkness Fall. Ballantine Books. p. 111.

- ^ Melville, Herman (1851). Moby-Dick, or, the Whale. Vol. c.1. London: Harper & Brothers. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.62077.

- This article is based on an earlier version by James Allan Evans, originally posted at Nupedia.

Bibliography

[edit]- Börm, Henning (2007). Prokop und die Perser. Untersuchungen zu den römisch-sasanidischen Kontakten in der ausgehenden Spätantike [Procopius and the Persians. Studies on the Roman-Sasanian contacts in late antiquity]. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-09052-0. (Review in English by G. Greatrex and Review in English by A. Kaldellis)

- Brodka, Dariusz: Prokop von Caesarea. Hildesheim: Olms 2022.

- Cameron, Averil (1985). Procopius and the Sixth Century. London: Duckworth.

- Cresci, Lia Raffaella (2001). "Procopio al confine tra due tradizioni storiografiche" [Procopius on the border between two historiographical traditions]. Rivista di Filologia e di Istruzione Classica. 129: 61–77.

- Evans, James A. S. (1972). Procopius. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2004). Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0241-0.

- Stewart, Michael (2020). Masculinity, Identity, and Power Politics in the Age of Justinian: A Study of Procopius. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-485-4025-9.

- Ziebuhr, Albrecht (2024). Die Exkurse im Geschichtswerk des Prokopios von Kaisareia: Literarische Tradition und spätantike Gegenwart in klassizistischer Historiographie [The digressions in the historical works of Prokopios of Kaisareia: literary tradition and the late antique present in classical historiography]. Hermes Einzelschriften. Vol. 126. Stuttgart: Steiner. ISBN 9783515136709.

Further reading

[edit]- Adshead, Katherine: Procopius' Poliorcetica: continuities and discontinuities, in: G. Clarke et al. (eds.): Reading the past in late antiquity, Australian National UP, Rushcutters Bay 1990, pp. 93–119

- Alonso-Núñez, J. M.: Jordanes and Procopius on Northern Europe, in: Nottingham Medieval Studies 31 (1987), 1–16.

- Amitay, Ory: Procopius of Caesarea and the Girgashite Diaspora, in: Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 20 (2011), 257–276.

- Anagnostakis, Ilias: Procopius's dream before the campaign against Libya: a reading of Wars 3.12.1-5, in: C. Angelidi and G. Calofonos (eds.), Dreaming in Byzantium and Beyond, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing 2014, 79–94.

- Bachrach, Bernard S.: Procopius, Agathias and the Frankish Military, in: Speculum 45 (1970), 435–441.

- Bachrach, Bernard S.: Procopius and the chronology of Clovis's reign, in: Viator 1 (1970), 21–32.

- Baldwin, Barry: An Aphorism in Procopius, in: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 125 (1982), 309–311.

- Baldwin, Barry: Sexual Rhetoric in Procopius, in: Mnemosyne 40 (1987), pp. 150–152

- Belke, Klaus: Prokops De aedificiis, Buch V, zu Kleinasien, in: Antiquité Tardive 8 (2000), 115–125.

- Börm, Henning: Procopius of Caesarea, in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, New York 2013.

- Börm, Henning: Procopius, his predecessors, and the genesis of the Anecdota: Antimonarchic discourse in late antique historiography, in: H. Börm (ed.): Antimonarchic discourse in Antiquity. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2015, 305–346.

- Braund, David: Procopius on the Economy of Lazica, in: The Classical Quarterly 41 (1991), 221–225.

- Brodka, Dariusz: Die Geschichtsphilosophie in der spätantiken Historiographie. Studien zu Prokopios von Kaisareia, Agathias von Myrina und Theophylaktos Simokattes. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004.

- Burn, A. R.: Procopius and the island of ghosts, in: English Historical Review 70 (1955), 258–261.

- Cameron, Averil: The scepticism of Procopius, in: Historia 15 (1966), 466–482.

- Colvin, Ian: Reporting Battles and Understanding Campaigns in Procopius and Agathias: Classicising Historians' Use of Archived Documents as Sources, in: A. Sarantis (ed.): War and warfare in late antiquity. Current perspectives, Leiden: Brill 2013, 571–598.

- Cristini, Marco: Il seguito ostrogoto di Amalafrida: confutazione di Procopio, Bellum Vandalicum 1.8.12, in: Klio 99 (2017), 278–289.

- Cristini, Marco: Totila and the Lucanian Peasants: Procop. Goth. 3.22.20, in: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 61 (2021), 73–84.

- Croke, Brian and James Crow: Procopius and Dara, in: The Journal of Roman Studies 73 (1983), 143–159.

- Downey, Glanville: The Composition of Procopius, De Aedificiis, in: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 78 (1947), 171–183.

- Evans, James A. S.: Justinian and the Historian Procopius, in: Greece & Rome 17 (1970), 218–223.

- Gordon, C. D.: Procopius and Justinian's Financial Policies, in: Phoenix 13 (1959), 23–30.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Procopius and the Persian Wars, D.Phil. thesis, Oxford, 1994.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: The dates of Procopius' works, in: BMGS 18 (1994), 101–114.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: The Composition of Procopius' Persian Wars and John the Cappadocian, in: Prudentia 27 (1995), 1–13.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Rome and Persia at War, 502–532. London: Francis Cairns, 1998.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Recent work on Procopius and the composition of Wars VIII, in: BMGS 27 (2003), 45–67.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Perceptions of Procopius in Recent Scholarship, in: Histos 8 (2014), 76–121 and 121a–e (addenda).

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Procopius of Caesarea: The Persian Wars. A Historical Commentary. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Howard-Johnson, James: The Education and Expertise of Procopius, in: Antiquité Tardive 10 (2002), 19–30

- Kaçar, Turhan: "Procopius in Turkey", Histos Supplement 9 (2019) 19.1–8.

- Kaegi, Walter: Procopius the military historian, in: Byzantinische Forschungen. 15, 1990, ISSN 0167-5346, 53–85 (online (PDF; 989 KB)).

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Classicism, Barbarism, and Warfare: Prokopios and the Conservative Reaction to Later Roman Military Policy, American Journal of Ancient History, n.s. 3-4 (2004-2005 [2007]), 189–218.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Identifying Dissident Circles in Sixth-Century Byzantium: The Friendship of Prokopios and Ioannes Lydos, Florilegium, Vol. 21 (2004), 1–17.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Prokopios’ Persian War: A Thematic and Literary Analysis, in: R. Macrides, ed., History as Literature in Byzantium, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010, 253–273.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Prokopios’ Vandal War: Thematic Trajectories and Hidden Transcripts, in: S. T. Stevens & J. Conant, eds., North Africa under Byzantium and Early Islam, Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2016, 13–21.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: The Date and Structure of Prokopios’ Secret History and his Projected Work on Church History, in: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, Vol. 49 (2009), 585–616.

- Kovács, Tamás: "Procopius's Sibyl - the fall of Vitigis and the Ostrogoths", Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24.2 (2019), 113–124.

- Kruse, Marion: The Speech of the Armenians in Procopius: Justinian's Foreign Policy and the Transition between Books 1 and 2 of the Wars, in: The Classical Quarterly 63 (2013), 866–881.

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher: "Hard and Soft Power on the Eastern Frontier: a Roman Fortlet between Dara and Nisibis, Mesopotamia, Turkey: Prokopios’ Mindouos?" in The Byzantinist, edited by Douglas Whalin, Issue 2 (2012), pp. 4–5, http://oxfordbyzantinesociety.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/obsnews2012final.pdf

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher: Procopius on the struggle for Dara and Rome, in A. Sarantis, N. Christie (eds.): War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives (Late Antique Archaeology 8.1–8.2 2010–11), Leiden: Brill 2013, pp. 599–630, ISBN 978-90-04-25257-8;

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher: “La defensa de Roma por Belisario” in: Justiniano I el Grande (Desperta Ferro) edited by Alberto Pérez Rubio, no. 18 (July 2013), pages 40–45, ISSN 2171-9276

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher (ed.): Procopius of Caesarea: Literary and Historical Interpretations. Routledge (2017), www.routledge.com/9781472466044;

- Maas, Michael Robert: Strabo and Procopius: Classical Geography for a Christian Empire, in H. Amirav et al. (eds.): From Rome to Constantinople. Studies in Honour of Averil Cameron, Leuven: Peeters, 2007, 67–84.

- Martindale, John: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire III, Cambridge 1992, 1060–1066.

- Max, Gerald E., "Procopius' Portrait of the (Western Roman) Emperor Majorian: History and Historiography," Byzantinische Zeitschrift, Sonderdruck Aus Band 74/1981, pp. 1–6.

- Meier, Mischa: Prokop, Agathias, die Pest und das ′Ende′ der antiken Historiographie, in Historische Zeitschrift 278 (2004), 281–310.

- Meier, Mischa and Federico Montinaro (eds.): A Companion to Procopius of Caesarea. Brill, Leiden 2022, ISBN 978-3-89781-215-4.

- Pazdernik, Charles F.: Xenophon’s Hellenica in Procopius’ Wars: Pharnabazus and Belisarius, in: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 46 (2006) 175–206.

- Rance, Philip: Narses and the Battle of Taginae (552 AD): Procopius and Sixth-Century Warfare, in: Historia. Zeitschrift für alte Geschichte 30.4 (2005) 424–472.

- Riemenschneider, Jakob (2024). Prokop und der soziale Kosmos der Historiographie: Exkurse, Diskurse und die römische Gesellschaft der Spätantike [Procopius and the social cosmos of historiography: digressions, discourses and Roman society in late antiquity]. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783111547640. ISBN 978-3-11-154686-5.

- Rubin, Berthold: Prokopios, in Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft 23/1 (1957), 273–599. Earlier published (with index) as Prokopios von Kaisareia, Stuttgart: Druckenmüller, 1954.

- Stewart, Michael, Contests of Andreia in Procopius’ Gothic Wars, Παρεκβολαι 4 (2014), pp. 21–54.

- Stewart, Michael, The Andreios Eunuch-Commander Narses: Sign of a Decoupling of martial Virtues and Hegemonic Masculinity in the early Byzantine Empire?, Cerae 2 (2015), pp. 1–25.

- Tougher, Shaun (1996). "Cameron and Beyond: A. Cameron, Procopius and the Sixth Century". Histos. 1. doi:10.29173/histos158. ISSN 2046-5963.

- Treadgold, Warren: The Early Byzantine Historians, Basingstoke: Macmillan 2007, 176–226.

- The Secret History of Art by Noah Charney on the Vatican Library and Procopius. An article by art historian Noah Charney about the Vatican Library and its famous manuscript, Historia Arcana by Procopius.

- Whately, Conor, Battles and Generals: Combat, Culture, and Didacticism in Procopius' Wars. Leiden, 2016.

- Whitby, Michael "Procopius and the Development of Roman Defences in Upper Mesopotamia", in P. Freeman and D. Kennedy (ed.), The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East, Oxford, 1986, 717–35.

External links

[edit]Texts of Procopius

[edit]- Works by Procopius in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Procopius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Procopius at the Internet Archive

- Works by Procopius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Complete Works, Greek text (Migne Patrologia Graeca) with analytical indexes

- The Secret History, English translation (Atwater, 1927) at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- The Secret History, English translation (Dewing, 1935) at LacusCurtius

- The Buildings, English translation (Dewing, 1935) at LacusCurtius

- The Buildings, Book IV Greek text with commentaries, index nominum, etc. at Sorin Olteanu's LTDM Project

- H. B. Dewing's Loeb edition of the works of Procopius: vols. I–VI at the Internet Archive (History of the Wars, Secret History)

- Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society (1888): Of the buildings of Justinian by Procopius, (ca 560 A.D)

- Complete Works 1, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 1, 1833. (Persian Wars I–II, Vandal Wars I–II)

- Complete Works 2, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 2, 1833. (Gothic Wars I–IV)

- Complete Works 3, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 3, 1838. (Secret History, Buildings of Justinian)

Secondary material

[edit]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Entry for Procopius from the Suda.

Procopius

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early Life and Origins

Procopius was born circa 500 AD in Caesarea Maritima, a coastal city in the eastern Roman province of Palaestina Prima (modern-day Israel).[8][6] Details of his family origins remain obscure, with no surviving records identifying his parents or social class beyond indications of sufficient means to afford elite education.[9] As a native of Caesarea, a Hellenistic center with a mixed Greek, Jewish, and Samaritan population, Procopius likely belonged to the Hellenized provincial elite, though scholarly debate persists on potential Samaritan or non-Christian influences in his background without conclusive evidence.[9] He received a thorough classical education, encompassing rhetoric, grammar, and possibly jurisprudence, as was standard for aspiring administrators in the late Roman East.[6][10] This training equipped him for roles in imperial service, reflecting the era's emphasis on sophistic skills for legal and diplomatic functions rather than specialized technical fields.[11] Prior to 527 AD, when he joined the staff of general Belisarius, Procopius held no documented public positions, suggesting his early career involved private rhetorical practice or minor provincial duties unrecorded in extant sources.[8]Military and Administrative Service

Procopius joined the imperial military administration in 527 as assessor—a role combining legal counsel, secretarial duties, and advisory functions—to General Belisarius during the initial phase of Justinian I's eastern campaigns against the Sassanid Persians.[1] In this capacity, he participated in key engagements, including the Roman victory at the Battle of Dara in 530, where Belisarius's forces repelled a larger Persian army through innovative defensive tactics and cataphract cavalry maneuvers, and the subsequent retreat following defeat at Callinicum in 531.[12] His position afforded him direct access to command decisions and battlefield observations, which later informed his detailed accounts in History of the Wars.[13] In 533, Procopius sailed with Belisarius's expeditionary force of approximately 16,000 men to North Africa, targeting the Vandal Kingdom.[14] The campaign culminated in swift victories at the Battle of Ad Decimum and the Battle of Tricamarum, leading to the capture of King Gelimer and the reestablishment of Roman control over the province by early 534, with Procopius documenting the logistical challenges and rapid maneuvers that minimized casualties. Returning briefly to Constantinople, he rejoined Belisarius in 535 for the Gothic War in Italy, where Roman forces invaded Sicily and then the mainland, besieging Naples via aqueduct infiltration and enduring the prolonged siege of Rome from 537 to 538 against Ostrogothic King Vitiges.[13] Procopius remained with the army through the reconquest of Ravenna in 540, providing logistical and legal support amid attritional warfare marked by plague outbreaks and supply shortages.[15] Following the Italian campaign's conclusion in 540, Procopius returned to Constantinople, where Justinian elevated him to the senatorial order as recognition of his service.[15] He transitioned to civilian administrative roles, culminating in his appointment as praefectus urbi (prefect of Constantinople) in 562, overseeing urban governance, public order, and infrastructure in the imperial capital during a period of fiscal strain and post-plague recovery.[8] This position reflected his accumulated expertise in imperial administration, though his writings suggest ongoing disillusionment with Justinian's policies, including heavy taxation to fund military endeavors.[16]Final Years and Death

In the later 550s, following the completion of his History of the Wars (which covers events up to approximately 554), Procopius appears to have advanced in imperial administration, receiving appointments that placed him in closer proximity to the court in Constantinople.[1] He is last explicitly attested in historical records around 559, during which time he may have undertaken roles involving oversight of public works or legal matters, consistent with his prior experience as an assessor (legal advisor) to Belisarius.[17] Scholars identify Procopius as potentially the same individual who served as praefectus urbi (prefect) of Constantinople in 562, a prestigious municipal position responsible for urban governance, finances, and infrastructure—a role that aligns with his demonstrated expertise in describing Justinian's building projects in his treatise On Buildings, completed around 558.[18] This appointment would mark a culmination of his career trajectory from military secretary to high civilian office, though direct evidence linking the two is inferential based on name rarity and chronological fit.[10] The precise date and circumstances of Procopius's death remain unknown, with estimates varying due to the absence of contemporary obituaries or epitaphs. He is believed to have died sometime after 562, possibly before Emperor Justinian I's death in November 565, as no further writings or references to him appear in Byzantine sources postdating that year.[1] Traditional scholarly consensus places his death circa 565 in Constantinople, though some analyses suggest it could have occurred earlier in the 560s, reflecting the limited epigraphic or archival survival from the period.[19]Major Works

History of the Wars

History of the Wars (Greek: Πόλεμοι, Polemoi) is Procopius' eight-book account of Emperor Justinian I's military campaigns against eastern and western barbarians from 527 to approximately 553.[20] Procopius, serving as legal assessor to General Belisarius, provided detailed eyewitness narratives of key operations, emphasizing tactics, logistics, and individual exploits while modeling his style on classical historians like Thucydides.[21] The first seven books were likely published around 550–551, with Book VIII added shortly thereafter to cover ongoing events.[22] The work divides into three main sections: Books I–II detail the Persian War against the Sassanid Empire, spanning intermittent conflicts from Justinian's accession, including the 530 Battle of Dara and the 532 "Eternal Peace" truce, though hostilities resumed by 540 with Persian incursions into Syria.[23] Books III–IV cover the Vandalic War, chronicling Belisarius' rapid 533–534 reconquest of North Africa from the Vandals, featuring the decisive Battle of Ad Decimum and the siege of Carthage, which restored Roman control over former provinces with minimal forces of about 15,000 men.[20] Books V–VIII address the protracted Gothic War for Italy against the Ostrogoths, beginning with Belisarius' 535 invasion of Sicily and mainland advances, capturing Rome in 536 after a siege, but extending into stalemated campaigns under successors like Narses, culminating in Totila's 552 defeat at Taginae and failed Gothic revivals.[24] Procopius integrates geographical digressions, ethnographic notes on foes like Persians and Goths, and critiques of strategy, such as logistical strains from overextended supply lines and plague impacts during the Gothic phase.[25] While praising Belisarius' generalship, he notes imperial resource constraints, with armies often numbering under 20,000 despite vast territories reconquered, highlighting the fragility of these victories amid internal rebellions and external pressures.[21] The narrative serves as the primary contemporary source for these reconquests, offering tactical granularity corroborated by archaeology, such as fortifications at Dara, though Procopius omits broader economic costs.[23]Buildings of Justinian

Procopius composed De Aedificiis (On Buildings), also known as the Buildings of Justinian, as a panegyric cataloging the architectural and infrastructural projects undertaken during Emperor Justinian I's reign from 527 to 565. Written likely between 554 and 560, shortly after completing his Wars, the text emphasizes Justinian's role in reconstructing churches, fortifications, aqueducts, bridges, and public works damaged by invasions, earthquakes, and neglect, portraying these efforts as divine restorations of Roman imperial grandeur.[26] Procopius frames the emperor's initiatives as fulfilling biblical and classical precedents, such as Solomon's temple, while attributing successes to Justinian's piety and administrative foresight rather than fiscal strain or coercion.[27] The work spans five books, beginning with Constantinople's landmarks in Book I, including the Hagia Sophia—described as a vast domed basilica with a central dome spanning 184 feet in diameter, supported by four massive piers and pendentives, completed in 537 after an earlier collapse—and the city's aqueducts, cisterns, and walls reinforced against Persian and Hunnic threats. Subsequent books detail provincial restorations: Book II covers Asia Minor and the eastern frontiers with monasteries, harbors, and bridges like those over the Sangarius River; Book III addresses Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, highlighting churches such as the Nea in Jerusalem and Nile irrigation repairs; Book IV focuses on Europe, including Illyricum's fortifications; and Books IV and V extend to North Africa, Italy, and frontier defenses like the Long Walls of Thrace and Dara's citadel, completed by 540 with advanced siege-resistant features. Procopius quantifies impacts, such as aqueducts supplying water to over 100,000 residents daily in Constantinople, and notes conversions of pagan temples into churches, aligning with Justinian's Christianization policies.[28] Though rich in technical details corroborated by archaeology—such as the Hagia Sophia's engineering and Dara's moats—the text exhibits rhetorical exaggeration, omitting massive costs estimated at hundreds of millions of solidi, reliance on corvée labor, and selective focus on successes amid ongoing fiscal crises post-reconquests.[29] This laudatory tone contrasts sharply with Procopius' Secret History, suggesting De Aedificiis served propagandistic aims, possibly to curry imperial favor or counterbalance critical undertones in his military histories, as evidenced by its dedication to Justinian and emphasis on the emperor's personal oversight.[30] Scholars assess its reliability as high for descriptive accuracy when cross-verified with inscriptions and excavations, but low for economic or motivational claims, viewing it as ekphrastic rhetoric linking buildings to Justinian's virtues rather than impartial record.[31] In frontier engineering, Procopius details bridges like the Sangarius spans in Bithynia, rebuilt with stone arches to facilitate military logistics and commerce, underscoring Justinian's strategic investments in connectivity amid Persian wars. The work's abrupt ending in Book VII, mid-description of Persian borders, indicates incompleteness, potentially due to Procopius' death around 565 or shifting priorities.[31] Despite biases toward imperial apologia, De Aedificiis remains a primary testament to sixth-century Byzantine engineering prowess, influencing later medieval views of Justinian as a builder-emperor.[32]Secret History

The Secret History, also known as the Anecdota or Historia Arcana, is a polemical work attributed to Procopius, composed in Greek around 550 AD during the reign of Emperor Justinian I, though some scholars propose a slightly later date of circa 559 based on references to Justinian's 32 years in power.[33][34] Intended for a small circle of trusted readers rather than public dissemination, it remained unpublished during Procopius' lifetime and was first edited and printed in 1623 by Niccolò Alamanni, who titled it Arcana Historia.[34] The text's authenticity, once debated in the 17th and 18th centuries, is now widely accepted by scholars due to linguistic and stylistic consistencies with Procopius' other works, such as the Wars and Buildings.[35] In the Secret History, Procopius contrasts the laudatory portrayals in his public histories by depicting Justinian and Empress Theodora as tyrannical and morally corrupt figures whose actions precipitated the empire's misfortunes, including military setbacks, economic woes, and natural disasters like the 542 plague.[36] He accuses Justinian of demonic qualities, claiming the emperor shape-shifted, abstained unnaturally from food and sleep, and orchestrated fiscal ruin through excessive taxation and confiscations that halved the empire's wealth.[37] Theodora is portrayed as a former actress and courtesan whose pre-marital life involved public indecencies, such as performing in mimes with geese and enduring sexual excesses, after which she wielded unchecked influence over Justinian, promoting favorites and persecuting rivals through torture and execution.[38] The work also levels criticisms at generals like Belisarius for cowardice and his wife Antonina for adultery, framing court intrigues as driven by lust, greed, and supernatural malevolence rather than rational policy.[36] Scholars interpret the Secret History as a rhetorical invective rather than objective history, employing hyperbolic Classical models like Herodotus and Thucydides to vent personal disillusionment amid Procopius' service under Justinian, possibly composed as a safeguard against regime collapse or posthumous revelation.[39] Its uneven structure and digressions suggest it was not designed as an independent narrative but as a supplement to Procopius' official accounts, exaggerating vices to explain perceived failures in Justinian's reconquests and administration.[39] While invaluable for insights into Byzantine elite scandals and anti-Justinian sentiment, the text's reliability is tempered by its polemical tone; corroborating evidence for specific claims, such as Theodora's early biography, is scant and often derived from hostile traditions, underscoring Procopius' selective emphasis on moral causation over empirical causality.[38][39]Historiographical Approach

Classical Models and Emulation

Procopius consciously modeled his History of the Wars on the works of ancient Greek historians, particularly Thucydides and Herodotus, to align his narrative with the classical tradition of rigorous inquiry and structured historiography. The preface to Book I of Wars explicitly echoes Thucydides' emphasis on the magnitude of events as justification for historical writing, portraying Justinian's campaigns against Persians, Vandals, and Goths as comparable in scale to the Peloponnesian War, thereby claiming enduring significance for his account.[30] Similarly, it incorporates Herodotus' motif of historiē (inquiry) by framing the work as a systematic investigation into contemporary conflicts, evoking the Greco-Persian Wars to underscore themes of Eastern threats to the Roman order.[30] [1] In narrative technique, Procopius adopted Thucydidean elements such as composed speeches to convey strategic deliberations before battles, a device used to dramatize decision-making without direct verbatim reporting, as seen in his accounts of Belisarius' councils during the Vandal and Gothic wars.[40] This emulation extended beyond structure to analytical depth, with Procopius mirroring Thucydides' focus on causation through human agency and contingency, analyzing military setbacks—like the plague's impact on Roman forces in 542—as pivotal turning points rather than divine interventions.[41] Herodotian influences appear in ethnographic digressions, such as detailed descriptions of Persian customs, Moorish tribes, and Gothic migrations, which provide cultural context for military engagements and reflect a broader curiosity about "barbarian" societies akin to Herodotus' inquiries into Scythians and Egyptians.[1] [42] Procopius also drew from Polybius' pragmatic approach, emphasizing logistical and political factors in empire-building, as evident in his treatment of Justinian's administrative reforms and alliances, which he presents as rational responses to imperial overextension rather than mere chronology.[43] This synthesis of models allowed Procopius to position himself as the culmination of classical historiography, writing in Attic Greek to evoke continuity with predecessors while adapting their methods to sixth-century Byzantine realities. Scholarly analyses, drawing from manuscript traditions and comparative stylistics, confirm these parallels without evidence of direct plagiarism, attributing them to deliberate rhetorical training in late antique education.[1] [42] Such emulation, however, occasionally strained under Procopius' pro-Belisarius bias, diverging from Thucydides' professed impartiality by minimizing Roman defeats.[40]Stylistic Features and Rhetoric

Procopius employed a classicizing Attic Greek in his writings, characterized by archaic vocabulary, complex syntax, and avoidance of contemporary koine influences, deliberately evoking the linguistic rigor of fifth-century BCE historians like Thucydides. This stylistic choice, informed by his rhetorical education, prioritized analytical precision over accessibility, resulting in dense prose that demands familiarity with classical models; for instance, he selectively imitates Thucydidean constructions such as genitive absolutes and indirect discourse to convey strategic deliberations and causal chains in military narratives.[24] [44] In the History of the Wars, this manifests in impersonal reporting of events, with emphasis on contingency and human decision-making, as seen in detailed accounts of sieges like Rome in 536 CE, where tactical minutiae underscore commanders' rationales without overt moralizing.[4] Rhetorically, Procopius adhered to ancient conventions by incorporating invented speeches (logoi hypothetikoi) that reconstruct plausible arguments rather than verbatim records, a technique he justifies by distinguishing historiography's demand for truth from rhetoric's allowance for embellishment. These orations, often placed before battles or councils, serve to elucidate motivations—such as Belisarius' addresses to troops during the Vandal campaign of 533–534 CE—and heighten dramatic tension, while ethnographic digressions on groups like the Moors or Persians echo Herodotan inquiry to contextualize imperial conflicts. [45] He further deploys ekphrasis for vivid spatial descriptions, as in siege engine depictions or urban fortifications, blending factual topography with rhetorical vividness to immerse readers in the scene's immediacy.[4] Across works, Procopius' rhetoric integrates allusion and intertextuality, opening the Wars with phrases mirroring Herodotus' and Thucydides' preambles to claim continuity with foundational historiography, while Homeric similes sporadically illustrate chaos in combat, such as comparing Persian retreats to routed Trojans. In the Buildings, this shifts toward panegyric, employing hyperbolic encomia and divine causality to frame Justinian's projects—like the Sangarius Bridge completed circa 560 CE—as restorations of Roman order, though tempered by subtle qualifications revealing structural pragmatism.[45] [31] Such devices not only persuade through familiarity but also critique implicitly, as digressions and asides in the Wars highlight logistical failures, balancing encomiastic potential with empirical observation.Reliability and Interpretations

Apparent Contradictions Between Works

The History of the Wars and Buildings of Justinian portray Emperor Justinian I as a restorer of Roman glory through military reconquests—such as the Vandalic War in North Africa (533–534 CE) and Gothic War in Italy (535–554 CE)—and extensive public works, including the reconstruction of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople after the Nika riots of 532 CE, framed as acts of prudent governance and divine providence.[46] In stark opposition, the Secret History (composed circa 550 CE) depicts Justinian as a shape-shifting demon who instigated famines, plagues, and legal persecutions for personal gain, asserting that his policies caused the deaths of millions through famine and disease between 540–550 CE alone.[6][47] Particular tensions arise in depictions of infrastructure: Buildings lauds Justinian's frontier fortifications, aqueducts, and churches—such as those along the eastern limes against Persia—as strategic and charitable investments totaling over 4,000 projects empire-wide.[46] Yet the Secret History condemns these as "stupid buildings" erected through extortionate taxes on impoverished subjects, yielding no practical benefit and exacerbating economic collapse, with funds diverted from essential military pay.[46] Similarly, while Wars credits Justinian's administration with logistical successes in campaigns like the African expedition under Belisarius, the Secret History accuses the emperor of betraying soldiers by withholding salaries, fostering mutinies, and prolonging futile wars for glory, such as the Italian conflicts that devastated the peninsula without sustainable gains.[6][48] The empress Theodora exemplifies personal vilification absent from the official works: Wars and Buildings omit or imply her as a stabilizing influence, but the Secret History details her pre-imperial life as a promiscuous actress involved in theatrical obscenities and post-accession intrigues, including orchestrating murders and sexual coercion within the court, portraying her as a catalyst for Justinian's tyrannical excesses.[6] These variances stem from the texts' divergent intents—the former as public historiography emulating Thucydides and Vitruvius for patronage, the latter as a suppressed invective possibly drafted earlier (circa 540 CE) for posthumous revelation—prompting debates on whether Procopius feigned loyalty in published works to evade persecution amid Justinian's purges of critics.[46][48] Scholarly consensus attributes all three to Procopius based on linguistic overlaps, viewing contradictions as deliberate rhetorical contrasts rather than forgery, though the Secret History's hyperbolic demonology (e.g., Justinian's nocturnal flights) undermines its literal reliability.[47][6]Scholarly Evaluations of Bias and Accuracy

Scholars generally assess Procopius' History of the Wars as a reliable primary source for Justinian's military campaigns, particularly those from 527 to 540 where he served as an eyewitness, with details on troop movements, battles, and logistics often corroborated by archaeological evidence and contemporary chronicles like those of Malalas.[30] However, evaluations highlight biases, including systematic exaggeration of enemy numbers—such as claiming 150,000 Ostrogoths against 5,000 Romans in 536–540—and partisan favoritism toward Belisarius, whom Procopius defends against failures while omitting compromising details like secret negotiations.[30] Suppression of critical views on Justinian appears motivated by fear of reprisal, as later revealed in the Secret History, yet the work's factual core remains robust when accounting for rhetorical embellishments drawn from Thucydides and Herodotus.[30] [42] The Secret History, by contrast, draws near-universal scholarly consensus as a highly biased polemic, characterized by vitriolic attacks on Justinian and Theodora that employ exaggeration, invective, and misogynistic tropes to portray them as demonic tyrants responsible for societal ills like fiscal oppression and moral decay.[49] While its lurid anecdotes, such as Theodora's alleged theatrical performances witnessed by crowds, strain credulity and reflect Procopius' elite disdain for her low origins and female influence, elements like critiques of bureaucratic overreach and religious persecution find partial corroboration in sources such as John the Lydian and Agapetus.[49] Anthony Kaldellis interprets it not as mere rant but as a philosophical exposé of tyranny rooted in classical political theory, suppressing Procopius' true republican sentiments to evade censorship in his public works.[50] [51] Recent scholarship, moving beyond positivist fact-checking, evaluates Procopius' overall accuracy through lenses of narratology and intertextuality, noting his selective omissions and heroic framing as deliberate classicizing strategies rather than wholesale fabrication, though reliability diminishes in non-eyewitness sections like the Gothic War's later books.[30] [42] No consensus exists on reconciling apparent contradictions across his oeuvre, with explanations ranging from evolving personal disillusionment post-540 to coded senatorial critique amid Justinian's centralizing reforms.[4] Despite biases, Procopius' works are deemed indispensable for sixth-century history when cross-verified, offering unique insights into Roman identity, warfare, and imperial ideology unattainable from fragmentary alternatives.[30]Corroboration with Other Sources

Procopius's military narratives in History of the Wars, particularly the Persian campaigns, receive support from archaeological investigations at key sites. Excavations at Dara (modern-day Oğuz, Turkey) have uncovered fortifications, walls, and a significant trench system that align closely with Procopius's description of the 530 AD battle preparations against the Sassanid forces, including tactical adaptations to terrain features he emphasized.[52] Similarly, evidence from Anatolian bridges and frontier structures, such as those along the Sangarius River, corroborates his accounts of logistical engineering during eastern expeditions.[53] Contemporary chroniclers provide textual validation for Procopius's event chronologies. John Malalas, writing in the mid-sixth century, confirms core details of the Nika riots in January 532 AD, including the imperial response that resulted in approximately 30,000 deaths in Constantinople's hippodrome, matching Procopius's scale and sequence in both Wars and Secret History.[34] Marcellinus Comes, a Latin annalist active under Justinian, parallels Procopius on the Vandal reconquest of 533–534 AD, noting Belisarius's fleet of 92 warships and 500 transports carrying 16,000 troops, which facilitated the rapid capture of Carthage after the Battle of Ad Decimum.[22] Successor historians extend and implicitly endorse Procopius's framework. Agathias, covering 552–559 AD in his Histories, adopts Procopius's stylistic and factual baseline for Gothic War aftermaths, such as Totila's defeat at Taginae in 552 AD, without disputing prior causal chains like plague impacts on Roman logistics.[54] Menander Protector, bridging to the 580s AD, continues this lineage by referencing Procopius's diplomatic precedents in Persian negotiations, including the 532 "Endless Peace" treaty terms, and aligns on Justinian's fiscal strains from prolonged conflicts.[55] In the Secret History, verifiable elements include administrative policies and crises, such as the Green faction's role in urban unrest and Justinian's centralizing edicts on provincial governance, which echo Malalas's records of senatorial purges post-Nika and fiscal reallocations documented in Justinian's Novellae corpus from 535–565 AD.[56] However, personal allegations against figures like Theodora lack independent attestation, though broader patterns of court intrigue align with Agathias's oblique references to imperial favorites influencing policy.[57]Enduring Impact

Influence on Later Historians

Agathias of Myrina explicitly continued Procopius' Wars with his own Histories, composed in the 570s and covering events from 552 to 559 CE, adopting a comparable classicizing style and narrative structure focused on military campaigns and diplomacy.[55] Menander Protector extended this tradition in the late sixth century by imitating Agathias' approach, which itself built upon Procopius' framework of detailed, secular reportage on Byzantine-Persian and internal affairs, thereby perpetuating a chain of historiographical continuity in the classicizing genre.[55] This emulation emphasized Thucydidean elements such as analytical speeches and causal explanations of events, influencing the rhetorical strategies of successors like Theophylact Simocatta, who referenced Procopius sparingly but operated within the same Attic Greek revivalist paradigm.[55] Procopius' integration of eyewitness testimony from Justinian's reconquests—spanning the Vandal War (533–534 CE), Gothic War (535–554 CE), and Persian fronts—provided a template for later Byzantine writers to blend panegyric with critical observation, though overt personal invective akin to the Secret History remained rare until its posthumous circulation.[55] In the Western tradition, direct influence during the early medieval period was minimal due to linguistic barriers and the primacy of Latin sources, but his accounts informed indirect perceptions of the sixth-century Mediterranean through excerpts in chronicles like those of Paul the Deacon (eighth century), with fuller impact emerging via Renaissance translations that revived interest in Byzantine military history. The Secret History's rediscovery around 1633 introduced a polemical dimension to historiography, prompting later scholars to grapple with authorial bias and multipartite authorship, though its medieval suppression limited contemporaneous emulation.[58] Overall, Procopius established a benchmark for comprehensive, event-driven history that prioritized empirical detail over hagiography, shaping Byzantine secular narrative until the shift toward ecclesiastical chronicles in the seventh century.[55]Role in Understanding Justinian's Era

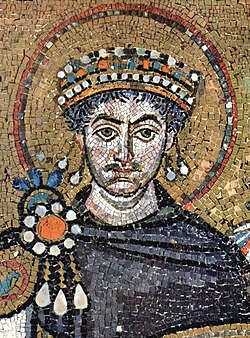

Procopius' "Wars," composed between approximately 550 and 562 CE, remains the most comprehensive surviving account of Justinian I's military endeavors, including the Persian campaigns of 527–532 CE, the Vandal reconquest in North Africa (533–534 CE), and the Gothic War in Italy (535–552 CE), drawing on his firsthand service as legal advisor to General Belisarius from 527 onward.[59] These narratives detail logistical challenges, battle tactics, and diplomatic maneuvers, such as the treaty with Persia in 532 CE (the "Endless Peace") and the rapid Vandal defeat at Tricamarum, corroborated by archaeological evidence like Vandal coin hoards and Italian fortifications.[11] While structured in classical Thucydidean style with speeches and causal analysis, the work's reliability for events is affirmed by alignments with contemporary laws, inscriptions, and later historians like Agathias, though it omits fiscal strains evident in tax records.[60] In "Buildings," completed around 560 CE, Procopius catalogs Justinian's infrastructural projects, such as the reconstruction of Hagia Sophia after the Nika revolt of 532 CE, aqueduct repairs supplying Constantinople with over 1,000 cubic meters of water daily, and frontier fortifications like the Long Walls of Thrace, providing metrics and engineering descriptions absent from other texts.[11] This panegyric complements official propaganda but offers verifiable details matching surviving structures and Justinian's edicts, illuminating administrative priorities amid post-plague recovery from the 541–542 CE pandemic, which Procopius describes with epidemiological precision in "Wars" Book II.[58] The "Secret History," likely drafted circa 550 CE but unpublished until the 11th century, supplements these with a vituperative portrayal of Justinian's court, alleging fiscal mismanagement leading to depopulation and attributing disasters to demonic influences, reflecting elite disillusionment rather than objective analysis.[61] Its value lies in highlighting tensions like senatorial resentment over Theodora's influence and legal reforms, partially echoed in Justinian's Novels (e.g., Novel 131 on fiscal equity), but hyperbolic elements—such as claims of 30–50 million deaths from policies—undermine credibility without corroboration, serving more as a lens for classical moral critique than empirical history.[62] Collectively, Procopius' oeuvre, despite authorial shifts from praise to invective, enables causal reconstruction of Justinian's era by integrating military expansion with internal strains, filling gaps in fragmentary sources like Marcellinus Comes or Malalas.[48] ![Justinian mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna][float-right]Scholarly consensus positions Procopius as indispensable for 6th-century Byzantine studies, with "Wars" prized for tactical granularity and the triad revealing regime contradictions, though interpretations must weigh his senatorial bias against material evidence like the Corpus Juris Civilis promulgation in 529–534 CE.[63]