Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adenoidectomy

View on Wikipedia| Adenoidectomy | |

|---|---|

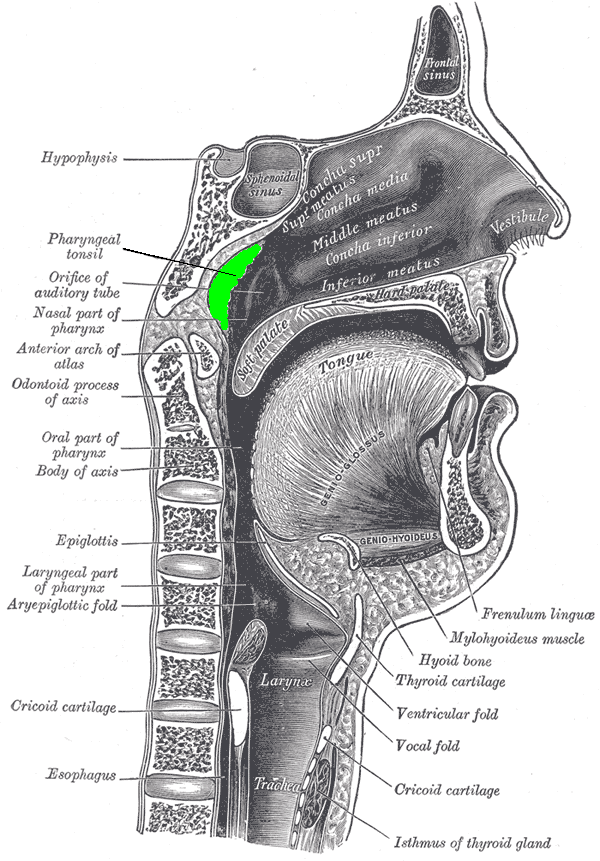

Location of the adenoid (colored in green) | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

| ICD-9-CM | 28 |

| MeSH | D000233 |

| MedlinePlus | 003011 |

| eMedicine | 872216 |

Adenoidectomy is the surgical removal of the adenoid for reasons which include impaired breathing through the nose, chronic infections, or recurrent earaches. The effectiveness of removing the adenoids in children to improve recurrent nasal symptoms and/or nasal obstruction has not been well studied.[1] The surgery is less commonly performed in adults in whom the adenoid is much smaller and less active than it is in children. It is most often done on an outpatient basis under general anesthesia. Post-operative pain is generally minimal and reduced by icy or cold foods. The procedure is often combined with tonsillectomy (this combination is usually called an "adenotonsillectomy" or "T&A"), for which the recovery time is an estimated 10–14 days, sometimes longer, mostly dependent on age.

Adenoidectomy is not often performed under one year of age as adenoid function is part of the body's immune system, but its contribution to this decreases progressively beyond this age.

Medical uses

[edit]The indications for adenoidectomy are still controversial.[2][3][4] Widest agreement surrounds the removal of the adenoid for obstructive sleep apnea, usually combined with tonsillectomy.[5] Even then, it has been observed that a significant percentage of the study population (18%) did not respond. There is also support for adenoidectomy in recurrent otitis media in children previously treated with tympanostomy tubes.[6] Finally, the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, common cold, otitis media and moderate nasal obstruction has been questioned with the outcome,[1] in some studies, being no better than watchful waiting.[7][8]

Frequency

[edit]

In 1971, more than one million Americans underwent tonsillectomies and/or adenoidectomies, of which 50,000 consisted of adenoidectomy alone.[9]

By 1996, roughly a half million children underwent some surgery on their adenoid and/or tonsils in both outpatient and inpatient settings. This included approximately 60,000 tonsillectomies, 250,000 combined tonsillectomies and adenoidectomies, and 125,000 adenoidectomies. By 2006, the total number had risen to over 700,000 but when adjusted for population changes, the tonsillectomy "rate" had dropped from 0.62 per thousand children to 0.53 per thousand. A larger decline for combined tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy was noted - from 2.20 per thousand to 1.46. There was no significant change in adenoidectomy rates for chronic infectious reasons (0.25 versus 0.21 per 1000).[10]

History

[edit]Adenoidectomy was first performed using a ring forceps through the nasal cavity by William Meyer in 1867.[11]

In the early 1900s, adenoidectomies began to be routinely combined with tonsillectomy.[12] Initially, the procedures were performed by otolaryngologists, general surgeons, and general practitioners but over the past 30 years have been performed almost exclusively by otolaryngologists.

Then, adenoidectomies were performed as treatment of anorexia nervosa, mental retardation, and enuresis or to promote 'good health'. By current standards, these indications seem odd but may be explained by the hypothesis that children might have failed to thrive if they had chronically sore throats or severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Also, children who heard poorly because of chronic otitis media might have had unrecognized speech delay mistaken for intellectual disability. Adenoidectomy might have helped to resolve ear fluid problems, speech delays, and consequent perceptions of low intelligence.

The relationship between enuresis and obstructive apnea, and the benefit of adenoidectomy by implication, is complex and controversial. On one hand, the frequency of enuresis declines as children grow older. On the other, the size of the adenoid, and again by implication, any obstruction that they might be causing, also declines with increasing age. These two factors make it difficult to distinguish the benefits of adenoidectomy from age-related spontaneous improvement. Further, most of the studies in the medical literature which appear to show benefit from adenoidectomy have been case reports or case series. Such studies are prone to unintentional bias. Finally, a recent study of six thousand children has not shown an association between enuresis and obstructive sleep in general but an increase with advancing severity of obstructive sleep apnea, observed only in girls.[13]

A decline in the frequency of the procedure started in the 1930s as its use became controversial. Tonsillitis and adenoiditis requiring surgery became less frequent with the development of antimicrobial agents and a decline in upper respiratory infections among older school-aged children. Also, several studies had shown that adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy were ineffective for many of the indications used at that time as well as the suggestion of an increased risk of developing poliomyelitis after the procedure, later disproved.[14] Prospective clinical trials, performed over the last 2 decades, have redefined the appropriate indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A), tonsillectomy alone, and adenoidectomy alone.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b van den Aardweg, Maaike Ta; Schilder, Anne Gm; Herkert, Ellen; Boonacker, Chantal Wb; Rovers, Maroeska M. (2010-01-20). "Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1) CD008282. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008282. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7105907. PMID 20091663.

- ^ Witt, R. L. (June 1989). "The tonsil and adenoid controversy". Delaware Medical Journal. 61 (6): 289–294. ISSN 0011-7781. PMID 2666179.

- ^ McClay, John E (2017-06-20). "Adenoidectomy: Background, History of the Procedure, Epidemiology". Medscape.

- ^ Bluestone, C. D.; Gates, G. A.; Paradise, J. L.; Stool, S. E. (November 1988). "Controversy over tubes and adenoidectomy". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 7 (11 Suppl): S146–149. doi:10.1097/00006454-198811001-00005. ISSN 0891-3668. PMID 3064039. S2CID 71533246.

- ^ Brietzke SE, Gallagher D (June 2006). "The effectiveness of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a meta-analysis". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134 (6): 979–84. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.033. PMID 16730542. S2CID 23177551.

- ^ Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Rogers KD, et al. (April 1990). "Efficacy of adenoidectomy for recurrent otitis media in children previously treated with tympanostomy-tube placement. Results of parallel randomized and nonrandomized trials". JAMA. 263 (15): 2066–73. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440150074029. PMID 2181158.

- ^ van den Aardweg MT, Boonacker CW, Rovers MM, Hoes AW, Schilder AG (2011). "Effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent upper respiratory tract infections: open randomised controlled trial". BMJ. 343 d5154. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5154. PMC 3167877. PMID 21896611.

- ^ Rynnel-Dagöö, Britta; Ahlbom, Anders; Schiratzki, Helge (2016-06-28). "Effects of Adenoidectomy". Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 87 (2): 272–278. doi:10.1177/000348947808700223. PMID 646300. S2CID 46456365.

- ^ a b "Frequency". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ Bhattacharyya N, Lin HW (November 2010). "Changes and consistencies in the epidemiology of pediatric adenotonsillar surgery, 1996–2006". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 143 (5): 680–4. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2010.06.918. PMID 20974339. S2CID 33142532.

- ^ "Tonsillitis, Tonsillectomy, and Adenoidectomy". Archived from the original on 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ "Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy". Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ Su MS, Li AM, So HK, Au CT, Ho C, Wing YK (August 2011). "Nocturnal enuresis in children: prevalence, correlates, and relationship with obstructive sleep apnea". J. Pediatr. 159 (2): 238–42.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.01.036. PMID 21397910.

- ^ Miller AH (July 1952). "Incidence of poliomyelitis; the effect of tonsillectomy and other operations on the nose and throat". Calif Med. 77 (1): 19–21. PMC 1521652. PMID 12978882.

- Bibliography

- Darrow D, Siemens C (2002). "Indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy". Laryngoscope. 112 (8 Pt 2 Suppl 100): 6–10. doi:10.1002/lary.5541121404. PMID 12172229. S2CID 24862952.

- Derkay C, Darrow D, LeFebvre S (1995). "Pediatric tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy procedures". AORN J. 62 (6): 885–904. doi:10.1016/S0001-2092(06)63556-4. PMID 9128745.

External links

[edit]Adenoidectomy

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Pathophysiology

The Adenoids

The adenoids, also known as the nasopharyngeal tonsils, are a mass of lymphoid tissue located on the posterior wall and roof of the nasopharynx. They form a key component of Waldeyer's ring, a circular arrangement of lymphoid structures that also includes the palatine tonsils, tubal tonsils, and lingual tonsil, collectively serving as a first line of defense in the upper respiratory and digestive tracts.[4][5] Adenoids undergo significant developmental changes throughout life. They begin to enlarge shortly after birth, reaching their peak size between ages 6 and 8 years, with a typical thickness of 12-14 mm at this stage. Following this period, the adenoids gradually atrophy after puberty, often becoming negligible or absent in adults by the late teens or early twenties.[6][7][8] Physiologically, the adenoids play a crucial role in childhood immunity, particularly in the upper respiratory tract. Composed primarily of B and T lymphocytes, they trap inhaled pathogens, facilitate antigen presentation, and produce antibodies to support both mucosal and systemic immune responses. This function is most prominent during early childhood when exposure to environmental antigens is high.[4][9][10] Anatomically, the adenoids are situated in close proximity to the Eustachian tube openings, the soft palate, and the nasal cavity, influencing airflow and middle ear ventilation. Their blood supply is primarily derived from the ascending pharyngeal artery, with contributions from the palatine and maxillary arteries, while venous drainage occurs via the pharyngeal plexus. Innervation is provided by branches of the glossopharyngeal (IX) and vagus (X) nerves through the pharyngeal plexus.[4][11][6] Diagnostic imaging of the adenoids typically involves lateral nasopharyngeal X-rays, where the adenoidal-nasopharyngeal (A/N) ratio is calculated by dividing the adenoid thickness by the nasopharyngeal depth; a ratio greater than 0.8 suggests hypertrophy. Flexible nasopharyngoscopy provides direct visualization, allowing for detailed assessment of size, surface characteristics, and any obstructive effects on adjacent structures.[6][12][13]Conditions Leading to Adenoidectomy

Adenoid hypertrophy refers to the abnormal enlargement of the adenoid tissue in the nasopharynx, which can obstruct airflow and lead to various respiratory and auditory symptoms. This condition primarily affects children between the ages of 2 and 7 years, with a prevalence of approximately 34.5%, though it often regresses spontaneously by adolescence. The hypertrophy obstructs the nasopharynx, resulting in nasal congestion, chronic mouth breathing, snoring, and hyponasal speech due to impaired nasal resonance. Common causes include chronic inflammation from repeated upper respiratory infections, allergic rhinitis, and environmental irritants such as cigarette smoke, which promote lymphoid tissue proliferation and mucosal edema.[6] Recurrent adenoid infections, or chronic adenoiditis, arise from persistent bacterial colonization and biofilm formation on the adenoid surface, creating a nidus for ongoing inflammation. Biofilms, composed of extracellular matrices harboring pathogens, shield bacteria from host defenses and antibiotics, leading to treatment-resistant infections lasting over 90 days. Predominant bacteria include Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, which form polymicrobial communities and contribute to recurrent rhinosinusitis and adenoiditis through continuous exudation and tissue irritation. This pathophysiology is exacerbated in children with frequent viral upper respiratory infections, fostering superinfections and lymphoid hyperplasia.[14][15] Adenoid hypertrophy is closely associated with otitis media through mechanical and infectious mechanisms involving the Eustachian tube. Enlarged adenoids physically block the nasopharyngeal openings of the Eustachian tubes, causing negative middle ear pressure, impaired mucociliary clearance, and accumulation of sterile or infected effusion. This leads to recurrent acute otitis media (AOM), defined as three or more episodes in six months, as well as persistent middle ear inflammation. Additionally, adenoids serve as a bacterial reservoir, with biofilms of H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae disseminating pathogens to the middle ear via retrograde migration, perpetuating the cycle of effusion and infection. Approximately 90% of children experience at least one episode of otitis media with effusion before school age, often linked to this adenoidal dysfunction.[16][15] Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children frequently stems from adenoid hypertrophy causing partial upper airway obstruction during sleep. The enlarged tissue narrows the nasopharynx, increasing upper airway resistance and leading to turbulent airflow, hypopnea, and apneic events characterized by oxyhemoglobin desaturation and hypercapnia. Diagnosis relies on polysomnography, the gold standard, which measures an obstructive apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) greater than 1 event per hour as indicative of obstructive sleep apnea within the SDB spectrum. This obstruction disrupts normal sleep architecture, contributing to daytime fatigue, behavioral issues, and growth delays in affected children.[17][18] Beyond these primary associations, adenoid hypertrophy plays a role in otitis media with effusion (OME), commonly known as glue ear, where persistent Eustachian tube blockage results in viscous middle ear fluid accumulation without acute infection, affecting up to 80% of children by age four. The adenoids contribute by serving as a site for bacterial persistence and by mechanically impeding tube ventilation, leading to hearing impairment and developmental delays if chronic. Furthermore, prolonged nasopharyngeal obstruction prompts habitual mouth breathing, which alters craniofacial growth patterns over time, resulting in adenoid facies—a characteristic long, narrow face with an open mouth posture, high-arched palate, and mandibular retrusion due to dysfunctional perioral muscles and atypical tongue positioning. This vicious cycle of hypertrophy and mouth breathing exacerbates malocclusions and increases anterior facial height in susceptible children.[19][20]Indications and Contraindications

Primary Indications

Adenoidectomy is primarily indicated for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children when adenoid hypertrophy contributes significantly to nasopharyngeal airway obstruction, and conservative management such as watchful waiting or medical therapy has failed. According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) clinical practice guidelines, surgery is recommended for pediatric OSA with symptoms including witnessed apneas, snoring, or daytime somnolence persisting for at least three months, particularly when adenotonsillar hypertrophy is the predominant factor.[21] Polysomnography is advised to confirm diagnosis in high-risk cases before proceeding.[21] For infectious indications, adenoidectomy is warranted in cases of recurrent or chronic rhinosinusitis unresponsive to maximal medical therapy, defined as symptoms lasting 90 days or more, or at least four episodes per year, following trials of antibiotics and intranasal corticosteroids.[21] For recurrent acute otitis media (AOM), adenoidectomy may be considered when adenoid hypertrophy is a contributing factor, particularly after failure of medical management and often in conjunction with myringotomy tube placement, per general pediatric guidelines for recurrent infections (e.g., ≥3 episodes in 6 months or ≥4 in 12 months).[22] These thresholds ensure intervention targets persistent adenoiditis contributing to infection cycles. Otologic indications include persistent otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting more than three months in children aged four years or older, where adenoid hypertrophy is the primary obstructing factor.[21] The AAO-HNS guidelines recommend against routine adenoidectomy for OME in children under four years unless distinct nasal obstruction is present, prioritizing tympanostomy tubes or observation first (2016 guideline).[23] Adenoidectomy is frequently combined with tonsillectomy for adenotonsillar hypertrophy causing OSA. Randomized controlled trials support 70-90% resolution of OSA symptoms post-adenotonsillectomy, though polysomnographic normalization may be lower at 60-80%, underscoring the procedure's efficacy after conservative approaches.[24] The 2019 AAO-HNS tonsillectomy guidelines emphasize initial nonsurgical management for mild cases before considering combined procedures.[25]Contraindications

Adenoidectomy has no universally recognized absolute contraindications, though certain conditions may preclude the procedure due to excessive perioperative risks. These include uncontrolled bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia with factor VIII or IX levels below 50% despite replacement therapy, which significantly elevate the risk of intraoperative or postoperative hemorrhage.[26][1] Active, untreated upper airway infections represent another absolute barrier, as they increase the likelihood of surgical site complications and dissemination of infection under anesthesia.[1] Severe craniofacial anomalies that distort nasopharyngeal anatomy, such as Pierre Robin sequence with associated micrognathia and glossoptosis, also contraindicate the procedure due to challenges in airway management and access to the adenoid bed.[27][28] Relative contraindications warrant careful risk-benefit assessment and may necessitate modifications or deferral of surgery. Significant bleeding diathesis, even if partially correctable, requires preoperative optimization but remains a cautionary factor given the vascularity of the adenoid tissue.[29][1] Immunosuppressed states, such as those induced by active chemotherapy, heighten susceptibility to infection and impaired wound healing, making adenoidectomy relatively inadvisable without multidisciplinary input.[25] Neuromuscular disorders that amplify anesthesia risks, including respiratory compromise, further qualify as relative contraindications, particularly in patients with baseline instability.[25] Children under 2 years of age face higher complication rates, including bleeding and airway events, due to smaller anatomical structures and immature physiology, often leading to deferral unless benefits clearly outweigh risks.[30][31] Preoperative evaluation employs specific tools to mitigate these risks. Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and platelet count, are essential for patients with bleeding history to identify and address diatheses.[26] For those with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the STOP-BANG questionnaire assesses perioperative respiratory risks, guiding anesthesia planning and potential inpatient monitoring.[32] In special populations, additional caution applies. Adenoidectomy is rarely indicated in adults owing to natural adenoid atrophy after adolescence, limiting its utility beyond exceptional cases like persistent infection.[29] Patients with a history of velopharyngeal incompetence (VPI), often linked to submucous cleft palate, short palate, or syndromes like velocardiofacial, risk exacerbation of hypernasal speech and nasal regurgitation post-removal; partial adenoidectomy or conservative management is preferred in such instances.[1][29] The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) emphasizes shared decision-making for borderline cases, recommending thorough discussion of benefits versus risks, particularly in high-risk groups like those with comorbidities or young age (as of 2019 guidelines).[21][25]Surgical Procedure

Preoperative Evaluation and Preparation

The preoperative evaluation for adenoidectomy begins with a comprehensive history and physical examination conducted by an otolaryngologist (ENT specialist) to assess the necessity of surgery and identify any associated conditions. The history focuses on symptoms such as recurrent otitis media with effusion, obstructive sleep-disordered breathing, chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal obstruction, hyponasal speech, or sleep disturbances lasting at least three months, often corroborated by parental reports or sleep diaries.[1][21] A detailed ENT physical exam includes inspection of the oral cavity, palate, tonsils, and nasal airway, with nasopharyngoscopy using a flexible fiberoptic endoscope to directly visualize adenoid hypertrophy and grade its size relative to the nasopharynx—commonly employing a scale from 0 (no obstruction) to 4+ (complete airway obstruction, occupying over 75-100% of the nasopharyngeal space).[33][1] Additional components involve audiometry to evaluate for conductive hearing loss due to middle ear effusion and a sleep history to document snoring, apnea episodes, or daytime somnolence.[21][1] Diagnostic tests are tailored to confirm adenoid enlargement and rule out alternative causes. Flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy remains the gold standard for direct assessment of adenoid size and position, often supplemented by cephalometric X-rays or lateral neck radiographs to quantify the adenoid-nasopharyngeal ratio (AN ratio), where values greater than 0.80 are often associated with significant hypertrophy.[33][21][34] For patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), polysomnography is recommended to objectively measure apnea-hypopnea index and oxygen desaturation, particularly in cases of severe symptoms or comorbidities.[1] If chronic rhinosinusitis or allergic contributions are suspected, allergy testing such as skin prick tests or serum IgE levels may be performed to guide management.[21] Medical optimization is essential to verify that surgery is warranted after conservative measures fail. A trial of intranasal corticosteroids, such as mometasone or fluticasone, administered for 4-8 weeks, is often attempted to reduce adenoid size and alleviate symptoms like nasal obstruction, with studies showing significant improvement in up to 70% of cases without proceeding to surgery.[35] Antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanate for β-lactamase stable coverage) are prescribed for documented bacterial infections or persistent adenoiditis following at least two prior courses, lasting 2-4 weeks each.[21] Anesthesia planning involves a multidisciplinary approach to ensure safety, especially in pediatric patients. Preoperative laboratory tests are generally not required for healthy children but may be considered for screening anemia with a complete blood count (CBC) or coagulation studies (e.g., PT/PTT) if there is a personal or family history of bleeding disorders.[33][36] For patients with comorbidities, such as those with Down syndrome who may have congenital heart defects, cardiology consultation is obtained to optimize cardiac status and assess perioperative risks.[1][37] Patient education and informed consent are critical components of preparation to align expectations and reduce anxiety. Families receive detailed information on the procedure, including its indications (e.g., persistent adenoid hypertrophy causing airway obstruction or recurrent infections), potential risks such as bleeding or infection, and nonsurgical alternatives like ongoing medical therapy.[21][1] Standard instructions cover preoperative fasting (typically nil per os after midnight for solids, clear liquids up to 2 hours prior), medication adjustments (e.g., avoiding aspirin for 7-10 days), and anxiety management strategies, such as oral premedication with midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) for children.[36][38]Intraoperative Techniques

Adenoidectomy is performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation to secure the airway and facilitate surgical access to the nasopharynx.[39][40] The standard transoral approach involves the use of an adenoid curette, such as the Blair or Parkinson model, to scrape and remove adenoid tissue from the nasopharynx under direct visualization with a laryngeal mirror or indirectly.[41][42] Hemostasis is achieved through packing with gauze or the application of electrocautery to control bleeding from the surgical bed.[43] The procedure typically lasts 15 to 30 minutes.[2][44] Advanced techniques include endoscopic-powered adenoidectomy using a microdebrider, which allows for precise tissue removal under direct visualization and reduces the incidence of residual adenoid tissue to approximately 20% compared to higher rates with conventional methods.[45][46] Coblation, employing radiofrequency ablation, minimizes thermal injury to surrounding tissues while achieving effective ablation.[47][48] In selective cases, a transnasal endoscopic approach may be utilized for targeted removal, particularly when addressing specific anatomical challenges.[49] Adjunctive procedures are commonly performed concurrently; myringotomy with tympanostomy tube placement addresses otitis media with effusion by ventilating the middle ear, and tonsillectomy is combined in adenotonsillectomy, which accounts for the majority of cases involving adenoid removal.[50][51] Quality control during surgery involves intraoperative endoscopy to confirm complete adenoid removal, ensuring no visible tissue remnants and evaluating velopharyngeal closure to prevent postoperative issues.[52][53]Immediate Postoperative Management

In the immediate postoperative period following adenoidectomy, patients are typically monitored in a recovery room for 1 to 2 hours to assess vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and respiratory effort, to ensure stability after anesthesia emergence. Adenoidectomy is commonly performed as outpatient day surgery, with studies as of 2025 confirming feasibility and low rates of unplanned admissions in appropriate candidates.[54] Observation focuses on signs of bleeding, such as hematemesis or epistaxis, which can compromise the airway, and any respiratory distress; if bleeding occurs, immediate intervention by the surgical team is required.[21] Pain management begins with scheduled doses of acetaminophen (10-15 mg/kg every 4-6 hours) or ibuprofen (5-10 mg/kg every 6 hours), alternating as needed, while avoiding aspirin due to the risk of bleeding; opioids like codeine are generally discouraged in children owing to potential respiratory depression.[36][50] Airway management involves elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees to minimize swelling and facilitate drainage, with humidified oxygen supplementation provided if oxygen saturation falls below 92%; suctioning of oral secretions may be necessary to maintain patency.[50] Discharge criteria from the recovery area or same-day surgery unit include the patient being alert and oriented, maintaining stable vital signs for at least 1 hour, tolerating oral intake without vomiting, achieving adequate pain control, and demonstrating the ability to void. For younger children (under 3 years) or those with comorbidities, an overnight observation period may be warranted to monitor for delayed airway issues. Dietary instructions emphasize hydration to prevent dehydration, starting with clear liquids such as water, apple juice, or electrolyte solutions, and advancing to soft foods like applesauce or yogurt within the first 24 hours as tolerated; dairy products should be limited initially, as they can increase mucus production and exacerbate throat discomfort.[55] Patients are encouraged to sip fluids frequently, aiming for at least 1-2 liters per day in children, to promote healing and reduce the risk of scab dislodgement.[50] Common early symptoms in the first 24-48 hours include throat pain that typically peaks on postoperative days 1-2, managed with the aforementioned analgesics, a low-grade fever below 38.5°C (101.3°F) due to inflammatory response, and halitosis resulting from scab formation in the nasopharynx.[50] These symptoms are self-limiting but warrant monitoring; persistent fever above 38.5°C or increasing pain should prompt contact with the healthcare provider.[21] Follow-up is scheduled for 1-2 weeks postoperatively to evaluate wound healing, assess for residual infection or bleeding, and perform a hearing reevaluation if preoperative otitis media with effusion was present, ensuring optimal recovery outcomes.[21]Complications and Recovery

Potential Complications

Adenoidectomy is generally a safe procedure with an overall postoperative complication rate of approximately 2-5%, primarily involving minor issues that resolve without intervention.[56] Recent studies as of 2025 confirm overall low complication rates, with revision surgery for bleeding at 0.7% for isolated adenoidectomy, and emphasize the safety of day surgery approaches.[57] Technique choice influences risks, with coblation associated with lower bleeding than curettage.[47] Serious complications are uncommon, occurring in less than 2% of cases, and perioperative mortality is extremely rare, estimated at less than 1 in 10,000 procedures for pediatric ear, nose, and throat surgeries.[58] Risk factors such as young age, concurrent tonsillectomy, and underlying conditions like vascular anomalies or immunosuppression can elevate specific risks.[59] Hemorrhage represents the most frequent serious complication, divided into primary (intraoperative or within 24 hours postoperatively) and secondary (typically days 1-7). Primary hemorrhage occurs in less than 1% of cases and is usually managed with cautery or packing during surgery.[60] Secondary hemorrhage affects 0.5-3% of patients, often requiring return to the operating room for control, with incidence rates as low as 0.1-0.2% in large cohorts necessitating readmission or reoperation.[56][61] Risk factors include older age and anatomical variations like aberrant vessels.[62] Postoperative infection, including wound infection or transient bacteremia, is infrequent at less than 1%, with rates around 0.3% leading to outpatient evaluation or readmission.[56] It is managed conservatively with antibiotics, though incidence may rise in immunocompromised children.[63] Velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI), characterized by nasal regurgitation or hypernasal speech due to excessive adenoidal resection, carries a 1-5% risk, with transient symptoms appearing in up to 3-14% shortly after surgery but persisting in only about 1 in 1,500 cases.[64][65] Approximately 50% of cases resolve spontaneously within 6 months, while persistent VPI may require speech therapy or secondary surgical correction such as pharyngeal flap reconstruction.[66] Anesthesia-related complications, such as laryngospasm or aspiration, are rare, contributing to the low overall perioperative mortality.[63] In higher-risk pediatric populations, respiratory adverse events occur in 2-3% but are mitigated by careful monitoring.[67] Other complications include dental injury from the mouth gag (approximately 0.1%), nasopharyngeal stenosis (<1%), and adenoidal regrowth (1-2% in children under 5 years, often asymptomatic).[68][69] These are managed supportively or with revision surgery if symptomatic, with regrowth more common after incomplete initial resection.[70] Techniques like curettage may slightly increase certain risks compared to coblation, though overall rates remain low.[47]Recovery Process and Long-term Outcomes

Following adenoidectomy, patients typically experience short-term recovery involving pain management for 3 to 7 days, with discomfort often peaking around days 3 to 5 due to throat and ear soreness from referred pain.[71][72] Analgesics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen are recommended regularly during this period to control symptoms and promote rest. Most children can return to school or work within 5 to 10 days, provided they are no longer requiring frequent pain medication and feel generally well.[2][73] Activity restrictions include avoiding strenuous exercise or contact sports for at least 2 weeks to prevent bleeding or strain on the surgical site.[73] Symptom resolution occurs progressively, with improvements in nasal breathing and reduction in snoring often noticeable within 1 week as swelling subsides, though full resolution may take up to 2 weeks.[74] In cases of otitis media with effusion (OME), hearing recovery is typically achieved by 1 month postoperatively, with success rates of 80% to 90% reported in clinical studies evaluating middle ear function restoration.[75][76] Long-term outcomes demonstrate sustained benefits, including significant reductions in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), with mean decreases of approximately 3-14 events per hour reported in pediatric cohorts following adenoidectomy, though success rates vary and residual OSA may persist in many cases.[77] Adenoidectomy also lowers the recurrence of acute otitis media (AOM) by about 40%, as evidenced by reduced episode frequency in follow-up evaluations.[78] Persistent issues, such as minor voice changes due to hypernasality, are rare and usually resolve without intervention.[79] Monitoring during recovery involves parental education on warning signs, including fever exceeding 39°C (102°F) or excessive bleeding from the nose or mouth, which warrant immediate medical attention to rule out dehydration or infection.[80] Audiologic follow-up is recommended at 3 months to assess hearing improvements, particularly in OME cases.[80][82] Longitudinal studies confirm these benefits persist up to 5 years, with significant quality-of-life enhancements, including improved sleep quality as measured by the OSA-18 questionnaire in affected children.[83][84]Epidemiology and History

Frequency and Demographics

Adenoidectomy is one of the most common pediatric surgical procedures in the United States, with an estimated 129,000 procedures performed annually.[85] This figure reflects data from the early 2010s, though rates have shown variability, including temporary declines during the COVID-19 pandemic due to reduced elective surgeries.[86] Worldwide, adenoidectomy rates among children vary significantly, though precise global estimates are challenging due to reporting differences.[87] Demographically, adenoidectomy predominantly affects young children, with the highest incidence in the 3- to 5-year age group, accounting for the majority of cases.[87] The median age at surgery is around 4 years, and over 80% of procedures occur in children under 7 years old.[57] There is a slight male predominance, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.5:1.[57] As of 2025, large cohort studies confirm low complication and revision rates (1.4%), supporting its safety in this demographic.[57] Rates are notably higher in populations with elevated prevalence of related conditions like otitis media, such as Indigenous communities, where adenoid hypertrophy is more pronounced and contributes to increased surgical needs.[88] Historical trends indicate a peak in the 1970s, when over 1 million combined tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A) procedures were performed annually in the US.[29] By the 2010s, rates had declined by about 50%, largely due to evidence-based guidelines that reduced overuse for infectious indications, dropping from 2.20 to 1.46 procedures per 1,000 children.[89] As of the early 2020s, 70-80% of adenoidectomies are combined with tonsillectomy, reflecting overlapping indications like obstructive sleep apnea.[90] Geographic variation is substantial, with higher frequencies in developed countries compared to lower rates in resource-limited settings where access to specialized care is restricted. Internationally, (adeno)tonsillectomy rates range widely across countries, for example from 23 to 293 per 100,000 in a review of 31 countries, highlighting disparities in healthcare infrastructure and diagnostic practices.[91][92] Several factors influence adenoidectomy frequency, including socioeconomic status, which affects access to ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists and timely interventions.[93] Seasonal peaks occur post-respiratory infections, particularly in fall and winter, when adenoid inflammation is more common.[94] Epidemiologically, rising allergies contribute to increased indications, as allergic rhinitis promotes adenoid hypertrophy and related symptoms.[21]Historical Development

The adenoids, or pharyngeal tonsils, were first described anatomically in 1661 by German physician Conrad Victor Schneider, who referred to them as vegetations at the roof of the nasopharynx in his treatise De catarrhis. [95] Their clinical significance emerged later, with British aural surgeon James Yearsley noting in 1842 a connection between adenoidal hypertrophy and ear diseases, including deafness, after reporting a case where removal of posterior nasal tissue improved hearing. [96] The first adenoidectomy was performed in 1868 by Danish otolaryngologist Hans Wilhelm Meyer in Copenhagen, who used a nasal ring knife to remove "adenoid vegetations" in children suffering from nasal obstruction and related auditory issues, marking the procedure's origin as a targeted intervention for respiratory and ear complications. [97] Building on this, in 1885, German surgeon Jacob Gottstein introduced the transoral curette, a specialized instrument that allowed for more precise adenoid removal via the mouth, shifting the approach from purely nasal access and facilitating broader surgical adoption. [98] By the 1920s, adenoidectomy had achieved widespread use, frequently combined with tonsillectomy (T&A) and often performed without general anesthesia in staged operations to address recurrent infections, driven by the early 20th-century "focus of infection" theory linking tonsillar and adenoidal disease to systemic illnesses. [99] This peaked in the mid-1900s, when T&A became a routine procedure in the United States for managing chronic infections in children, reflecting its status as one of the most common surgeries until evidence began questioning its overuse. [99] Modern advancements refined the procedure's safety and efficacy, with powered instruments like microdebriders introduced in the 1990s for more controlled tissue removal, followed by endoscopic techniques that minimized complications such as bleeding and incomplete resection. [100] Guideline shifts, including the 2004 American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) evidence review on otitis media with effusion, helped curb unnecessary procedures by emphasizing selective indications. Key milestones include a 1971 U.S. peak of approximately 50,000 isolated adenoidectomies amid high procedure volumes, and 2019 AAO-HNS updates that prioritized obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as a primary indication while addressing antibiotic resistance concerns in infection management. [99][25]References

- https://wikianesthesia.org/wiki/Tonsillectomy_and/or_adenoidectomy

- https://www.[webmd](/page/WebMD).com/children/adenoiditis