Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Aevum.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aevum

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Aevum

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

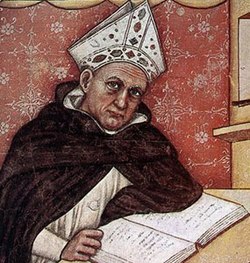

In scholastic philosophy, aevum (also known as aeviternity) denotes the intermediate mode of duration between temporal time and divine eternity, specifically characterizing the existence of angels, saints in heaven, and certain celestial bodies that possess immutable substance yet undergo limited change.[1] This concept distinguishes aevum from the successive "before and after" of human time, which measures mutable and changing things, and from eternity, which is the wholly simultaneous and boundless possession of unending life attributed solely to God.[1] As articulated by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica (Prima Pars, Question 10, Article 5), aevum serves as a mean between these extremes, allowing for a duration that is primarily simultaneous within itself but capable of annexing succession in its affections or operations, such as the intellectual acts of angels.[1]

The term originates from the Latin aevum, a second-declension noun meaning "lifetime," "age," "period of existence," or "eternity," often evoking neverending time or the span of a generation.[2] In classical Latin usage, it frequently appears in phrases like in aevum ("for all time") or flos aevi ("bloom of life"), underscoring its association with enduring yet bounded existence.[2] Medieval thinkers adapted this root to theological ends, building on earlier Neoplatonic influences to refine distinctions in divine and created being; for instance, Albertus Magnus explored aevum within his systematic treatment of time (aeternitas, aevum, tempus), viewing it as the participatory eternity shared by incorruptible creatures.[3]

Aquinas further elaborated that while time applies to the successive nature of spiritual creatures' wills and intellects, aevum measures their essential permanence, rejecting the notion that angelic existence is strictly temporal like corporeal motion.[1] He addressed potential objections, such as whether aevum implies infinite succession (which it does not, as it remains oriented toward simultaneity) or equates to time (which Augustine had suggested for spiritual affections, but Aquinas differentiated based on substance).[1] This framework influenced later scholastic debates; for example, John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham critiqued or modified aevum, with Ockham denying it as a distinct measure and aligning angelic duration more closely with time.[4] Despite such variations, aevum remains a cornerstone of medieval metaphysics, encapsulating the tension between change and immutability in the created order.[3]