Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Charlemagne

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Charlemagne (/ˈʃɑːrləmeɪn/ SHAR-lə-mayn; 2 April 748[a] – 28 January 814) was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian Empire from 800. He united most of Western and Central Europe and was the first recognised emperor to rule from the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's reign was marked by political and social changes that had lasting influence on Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

A member of the Frankish Carolingian dynasty, Charlemagne was the eldest son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon. With his brother Carloman I, he became king of the Franks in 768 following Pepin's death and became the sole ruler three years later. Charlemagne continued his father's policy of protecting the papacy and became its chief defender, removing the Lombards from power in northern Italy in 774. His reign saw a period of expansion that led to the conquests of Bavaria, Saxony, and northern Spain, as well as other campaigns that led Charlemagne to extend his rule over a large part of Europe. Charlemagne spread Christianity to his new conquests (often by force), as seen at the Massacre of Verden against the Saxons. He also sent envoys and initiated diplomatic contact with the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in the 790s, due to their mutual interest in Iberian affairs.

In 800 Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III. Although historians debate the coronation's significance, the title represented the height of his prestige and authority. Charlemagne's position as the first emperor in the West in over 300 years brought him into conflict with the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople. Through his assumption of the imperial title, he is considered the forerunner to the line of Holy Roman Emperors, which persisted into the 19th century. As king and emperor, Charlemagne engaged in numerous reforms in administration, law, education, military organisation, and religion, which shaped Europe for centuries. The stability of his reign began a period of cultural activity known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

Charlemagne died in 814 and was buried at the Palatine Chapel (now part of Aachen Cathedral) in Aachen, his imperial capital city. Charlemagne's profound influence on the Middle Ages and influence on the territory he ruled has led him to be called the "Father of Europe" by many historians. He is seen as a founding figure by multiple European states, and several historical royal houses of Europe trace their lineage back to him. Charlemagne has been the subject of artworks, monuments and literature during and after the medieval period.

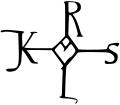

Name

[edit]Several languages were spoken in Charlemagne's world.[1][b] He was known as Karlo to Early Old French (or Proto-Romance) speakers and as Carolus (or Karolus) in Medieval Latin, the formal language of writing and diplomacy.[2][3] Charles is the modern English form of these names. The name Charlemagne, as the emperor is normally known in English, comes from the French Charles-le-magne ('Charles the Great').[4] In modern German and Dutch, he is known as Karl der Große and Karel de Grote respectively.[5] The Latin epithet magnus ('great') may have been associated with him during his lifetime, but this is not certain. The contemporary Royal Frankish Annals routinely call him Carolus magnus rex ("Charles the great king").[6] That epithet is attested in the works of the Poeta Saxo around 900, and it had become commonly applied to him by 1000.[7]

Charlemagne was named after his grandfather, Charles Martel.[8] That name and its derivatives are unattested before their use by Charles Martel and Charlemagne.[9] Karolus was adapted by Slavic languages as their word for "king" (Russian: korol', Polish: król and Slovak: král) through Charlemagne's influence or that of his great-grandson, Charles the Fat.[10]

Early life and rise to power

[edit]Political background and ancestry

[edit]

By the 6th century, the western Germanic tribe of the Franks had been Christianised; this was largely instigated by the conversion of King Clovis I to Catholicism.[11] The Franks had established a kingdom in Gaul in the wake of the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.[12] This kingdom, Francia, grew to encompass nearly all of present-day France and Switzerland, along with parts of modern Germany and the Low Countries under the rule of the Merovingian dynasty.[13] Francia was often divided under different Merovingian kings, due to the partible inheritance practised by the Franks.[14] The late 7th century saw a period of war and instability following the murder of King Childeric II, which led to factional struggles among the Frankish aristocrats.[15]

Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his 687 victory at the Battle of Tertry.[16] Pepin was the grandson of two important figures of Austrasia: Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen.[17] The mayors of the palace had gained influence as the Merovingian kings' power waned following divisions of the kingdom and several succession crises.[18] Pepin was eventually succeeded by his son Charles, later known as Charles Martel.[19] Charles did not support a Merovingian successor upon the death of King Theuderic IV in 737, leaving the throne vacant.[20] He made plans to divide the kingdom between his sons Carloman and Pepin the Short, who succeeded him after his death in 741.[21] The brothers placed the Merovingian Childeric III on the throne in 743.[22] In 744 Pepin married Bertrada, a member of an influential noble family.[23][24] In 747 Carloman abdicated and entered a monastery in Rome. He had at least two sons; the elder, Drogo, took his place.[25]

Birth

[edit]Charlemagne's year of birth is uncertain, although it was most likely in 748.[26][27][28][29] An older tradition based on three sources, however, gives a birth year of 742. The 9th-century biographer Einhard reports Charlemagne as being 72 years old at the time of his death; the Royal Frankish Annals imprecisely gives his age at death as about 71, and his original epitaph called him a septuagenarian.[30] Einhard said that he did not know much about Charlemagne's early life; some modern scholars believe that, not knowing the emperor's true age, he still sought to present a date in keeping with the Roman imperial biographies of Suetonius, which he used as a model.[31][32] All three sources may have been influenced by Psalm 90: "The days of our years are threescore years and ten".[33]

Historian Karl Ferdinand Werner challenged the acceptance of 742 as the Frankish king's birth year, citing an addition to the Annales Petaviani which records Charlemagne's birth in 747.[34][c] Lorsch Abbey commemorated Charlemagne's date of birth as 2 April from the mid-9th century, and this date is likely to be genuine.[35][36] Matthias Becher built on Werner's work and showed that 2 April in the year recorded would have actually been in 748, since the annalists recorded the start of the year from Easter rather than 1 January.[26] Presently, most scholars accept April 748 for Charlemagne's birth.[37][26][27] Charlemagne's place of birth is unknown: the Frankish palaces in Vaires-sur-Marne, Quierzy and Herstal[38] are among the places suggested by scholars;[39] Pepin the Short held an assembly in Düren in 748, but it cannot be proved that it took place in April or if Bertrada was with him.[40]

Language and education

[edit]

The patrius sermo ("native tongue")[39] that Einhard refers to with regard to Charlemagne, was a Germanic language.[42][43] Due to the prevalence in Francia of "rustic Roman", he was probably functionally bilingual in Germanic and Romance dialects at an early age.[39] Charlemagne also spoke Latin and, according to Einhard, could understand and (perhaps) speak some Greek.[44] Some 19th-century historians tried to use the Oaths of Strasbourg to determine Charlemagne's native language. They assumed that the text's copyist Nithard, being a grandson of Charlemagne, would have spoken the same dialect as his grandfather, giving rise to the assumption that Charlemagne would have spoken language closely related to the one used in the oath, which is a form of Old High German ancestral to the modern Rhenish Franconian dialects.[42][43] Other authors have instead taken the place of Charlemagne's education and main residence of Aachen to postulate that Charlemagne most likely spoke a form of Moselle- or Ripuarian Franconian. In any case, all three dialects would have been closely related, mutually intelligible and, while classified as Old High German, none of the dialects involved can be considered typical of Old High German, showing varying degrees of participation in the High German consonant shift as well as certain similarities with Old Dutch, the presumed language of the previous Merovingian dynasty, mirroring the linguistic diversity still typical of the region today.[39]

Charlemagne's father Pepin had been educated at the abbey of Saint-Denis, although the extent of Charlemagne's formal education is unknown.[45] He almost certainly was trained in military matters as a youth in Pepin's itinerant court.[46][47] Charlemagne also asserted his own education in the liberal arts in encouraging their study by his children and others, although it is unknown whether his study was as a child or at court during his later life.[46] The question of Charlemagne's literacy is debated, with little direct evidence from contemporary sources. He normally had texts read aloud to him and dictated responses and decrees, but this was not unusual even for a literate ruler at the time.[48] Historian Johannes Fried considers it likely that Charlemagne would have been able to read,[49] but the medievalist Paul Dutton writes "the evidence for his ability to read is circumstantial and inferential at best"[50] and concludes that it is likely that he never properly mastered the skill.[51] Einhard makes no direct mention of Charlemagne reading and records that he only attempted to learn to write later in life.[52]

Accession and reign with Carloman

[edit]There are only occasional references to Charlemagne in the Frankish annals during his father's lifetime.[53] By 751 or 752, Pepin had deposed Childeric and replaced him as king.[54] Early Carolingian-influenced sources claim that Pepin's seizure of the throne was sanctioned beforehand by Pope Stephen II,[55] but modern historians dispute this.[56][22] It is possible that papal approval came only when Stephen travelled to Francia in 754 (apparently to request Pepin's aid against the Lombards), and on this trip anointed Pepin as king; this legitimised his rule.[57][56] Charlemagne was sent to greet and escort Stephen, and he and his younger brother Carloman were anointed with their father.[58] Pepin sidelined Drogo around the same time, sending him and his half-brother Grifo to a monastery.[59]

Charlemagne began issuing charters in his own name in 760. The following year, he joined his father's campaign against Aquitaine.[60] Aquitaine, led by Dukes Hunald and Waiofar, was constantly in rebellion during Pepin's reign.[61] Pepin fell ill on campaign there and died on 24 September 768; Charlemagne and Carloman succeeded their father.[62] They had separate coronations, Charlemagne at Noyon and Carloman at Soissons, on 9 October.[63] The brothers maintained separate palaces and spheres of influence, although they were considered joint rulers of a single Frankish kingdom.[64] The Royal Frankish Annals report that Charlemagne ruled Austrasia and Carloman ruled Burgundy, Provence, Aquitaine, and Alamannia, with no mention of which brother received Neustria.[64] The immediate concern of the brothers was the ongoing uprising in Aquitaine.[65] They marched into Aquitaine together, but Carloman returned to Francia for unknown reasons and Charlemagne completed the campaign on his own.[65] Charlemagne's capture of Duke Hunald marked the end of ten years of war that had been waged in the attempt to bring Aquitaine into line.[65]

Carloman's refusal to participate in the war against Aquitaine led to a rift between the kings.[65][66] It is uncertain why Carloman abandoned the campaign; the brothers may have disagreed about control of the territory,[65][67] or Carloman was focused on securing his rule in the north of Francia.[67] Regardless of the strife between the kings, they maintained a joint rule for practical reasons.[68] Charlemagne and Carloman worked to obtain the support of the clergy and local elites to solidify their positions.[69]

Pope Stephen III was elected in 768 but was briefly deposed by Antipope Constantine II before being restored to Rome.[70] Stephen's papacy experienced continuing factional struggles, so he sought support from the Frankish kings.[71] Both brothers sent troops to Rome, each hoping to exert his own influence.[72] The Lombard King Desiderius also had interests in Roman affairs, and Charlemagne attempted to enlist him as an ally.[73] Desiderius already had alliances with Bavaria and Benevento through the marriages of his daughters to their dukes,[74] and an alliance with Charlemagne would add to his influence.[73] Charlemagne's mother Bertrada went on his behalf to Lombardy in 770 and brokered a marriage alliance before returning to Francia with his new bride.[75] Desiderius's daughter is traditionally known as Desiderata, although she may have been named Gerperga.[76][65] Anxious about the prospect of a Frankish–Lombard alliance, Pope Stephen sent a letter to both Frankish kings decrying the marriage and separately sought closer ties with Carloman.[77]

Charlemagne had already had a relationship with the Frankish noblewoman Himiltrude, and they had a son in 769 named Pepin.[63] Paul the Deacon wrote in his 784 Gesta Episcoporum Mettensium that Pepin was born "before legal marriage" but does not say whether Charles and Himiltrude ever married, were joined in a non-canonical marriage (friedelehe), or married after Pepin was born.[78] Pope Stephen's letter described the relationship as a legitimate marriage, but he had a vested interest in preventing Charlemagne from marrying Desiderius's daughter.[79]

Carloman died suddenly on 4 December 771, leaving Charlemagne sole king of the Franks.[80] He moved immediately to secure his hold on his brother's territory, forcing Carloman's widow Gerberga to flee to Desiderius's court in Lombardy with their children.[81][82] Charlemagne ended his marriage to Desiderius's daughter and married Hildegard, daughter of Count Gerold, a powerful magnate in Carloman's kingdom.[82] This was a reaction to Desiderius's sheltering of Carloman's family[83] and a move to secure Gerold's support.[84][85]

King of the Franks and the Lombards

[edit]Annexation of the Lombard Kingdom

[edit]

Charlemagne's first campaigning season as sole king of the Franks was spent on the eastern frontier in his first war against the Saxons, who had been engaging in border raids on the Frankish kingdom when Charlemagne responded by destroying the pagan Irminsul at Eresburg and seizing their gold and silver.[86] The success of the war helped secure Charlemagne's reputation among his brother's former supporters and funded further military action.[87] The campaign was the beginning of over 30 years of nearly-continuous warfare against the Saxons by Charlemagne.[88]

Pope Adrian I succeeded Stephen III in 772 and sought the return of papal control of cities that had been captured by Desiderius.[89] Unsuccessful in dealing with Desiderius directly, Adrian sent emissaries to Charlemagne to gain his support for recovering papal territory. Charlemagne, in response to this appeal and the dynastic threat of Carloman's sons in the Lombard court, gathered his forces to intervene.[90] He first sought a diplomatic solution, offering gold to Desiderius in exchange for the return of the papal territories and his nephews.[91] This overture was rejected, and Charlemagne's army (commanded by himself and his uncle, Bernard) crossed the Alps to besiege the Lombard capital of Pavia in late 773.[92]

Charlemagne's second son (also named Charles) was born in 772, and Charlemagne brought the child and his wife to the camp at Pavia. Hildegard was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter named Adelhaid. The baby was sent back to Francia but died on the way.[92] Charlemagne left Bernard to maintain the siege at Pavia while he took a force to capture Verona, where Desiderius's son Adalgis had taken Carloman's sons.[93] Charlemagne captured the city; no further record exists of his nephews or of Carloman's wife, and their fate is unknown.[94][95] British historian Janet Nelson compares them to the Princes in the Tower in the Wars of the Roses.[96] Fried suggests that the boys were forced into a monastery (a common solution of dynastic issues), or "an act of murder smooth[ed] Charlemagne's ascent to power."[97] Adalgis was not captured by Charlemagne and fled to Constantinople.[98]

Charlemagne left the siege in April 774 to celebrate Easter in Rome.[99] Pope Adrian arranged a formal welcome for the Frankish king, and they swore oaths to each other over the relics of St. Peter.[100] Adrian presented a copy of the agreement between Pepin and Stephen III outlining the papal lands and rights Pepin had agreed to protect and restore.[101] It is unclear which lands and rights the agreement involved, which remained a point of dispute for centuries.[102] Charlemagne placed a copy of the agreement in the chapel above St. Peter's tomb as a symbol of his commitment, and he left Rome to continue the siege.[103]

Disease struck the Lombards shortly after his return to Pavia, and they surrendered the city by June 774.[104] Charlemagne deposed Desiderius and took the title of King of the Lombards.[105] The takeover of one kingdom by another was "extraordinary",[106] and the authors of The Carolingian World call it "without parallel".[95] Charlemagne secured the support of the Lombard nobles and Italian urban elites to seize power in a mainly-peaceful annexation.[106][107] Historian Rosamond McKitterick suggests that the elective nature of the Lombard monarchy eased Charlemagne's takeover,[108] and Roger Collins attributes the easy conquest to the Lombard elite's "presupposition that rightful authority was in the hands of the one powerful enough to seize it".[106] Charlemagne soon returned to Francia with the Lombard royal treasury and with Desiderius and his family, who would be confined to a monastery for the rest of their lives.[109]

Frontier wars in Saxony and Spain

[edit]

The Saxons took advantage of Charlemagne's absence in Italy to raid the Frankish borderlands, leading to a Frankish counter-raid in the autumn of 774 and a reprisal campaign the following year.[110] Charlemagne was drawn back to Italy as Duke Hrodgaud of Friuli rebelled against him.[111] He quickly crushed the rebellion, distributing Hrodgaud's lands to the Franks to consolidate his rule in Lombardy.[112] Charlemagne wintered in Italy, consolidating his power by issuing charters and legislation and taking Lombard hostages.[113] Amid the 775 Saxon and Friulian campaigns, his daughter Rotrude was born in Francia.[114]

Returning north, Charlemagne waged another brief, destructive campaign against the Saxons in 776.[e] This led to the submission of many Saxons, who turned over captives and lands and submitted to baptism.[116] In 777, Charlemagne held an assembly at Paderborn with Frankish and Saxon men; many more Saxons came under his rule, but the Saxon magnate Widukind fled to Denmark to prepare for a new rebellion.[117]

Also at the Paderborn assembly were representatives of dissident factions from al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). They included the son and son-in-law of Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri, the former governor of Córdoba ousted by Caliph Abd al-Rahman in 756, who sought Charlemagne's support for al-Fihri's restoration. Also present was Sulayman al-Arabi, governor of Barcelona and Girona, who wanted to become part of the Frankish kingdom and receive Charlemagne's protection rather than remain under the rule of Córdoba.[118] Charlemagne, seeing an opportunity to strengthen the security of the kingdom's southern frontier and extend his influence, agreed to intervene.[119] Crossing the Pyrenees, his army found little resistance until an ambush by Basque forces in 778 at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. The Franks, defeated in the battle, withdrew with most of their army intact.[120]

Building the dynasty

[edit]

Charlemagne returned to Francia to greet his newborn twin sons, Louis and Lothair, who were born while he was in Spain;[121] Lothair died in infancy.[122] Again, Saxons had seized on the king's absence to raid. Charlemagne sent an army to Saxony in 779[123] while he held assemblies, legislated, and addressed a famine in Francia.[124] Hildegard gave birth to another daughter, Bertha.[122] Charlemagne returned to Saxony in 780, holding assemblies at which he received hostages from Saxon nobles and oversaw their baptisms.[125]

He and Hildegard travelled with their four younger children to Rome in the spring of 781, leaving Pepin and Charles at Worms, to make a journey first requested by Adrian in 775.[122] Adrian baptised Carloman and renamed him Pepin, a name he shared with his half-brother.[126] Louis and the newly renamed Pepin were then anointed and crowned. Pepin was appointed king of the Lombards, and Louis king of Aquitaine.[115] This act was not nominal, since the young kings were sent to live in their kingdoms under the care of regents and advisers.[127] A delegation from the Byzantine Empire, the remnant of the Roman Empire in the East, met Charlemagne during his stay in Rome; Charlemagne agreed to betroth his daughter Rotrude to Empress Irene's son, Emperor Constantine VI.[128]

Hildegard gave birth to her eighth child, Gisela, during this trip to Italy.[129] After the royal family's return to Francia, she had her final pregnancy and died from its complications on 30 April 783. The child, named after her, died shortly thereafter.[130] Charlemagne commissioned epitaphs for his wife and daughter and arranged for a Mass to be said daily at Hildegard's tomb.[130] Charlemagne's mother Bertrada died shortly after Hildegard, on 12 July 783.[131] Charlemagne was remarried to Fastrada, daughter of East Frankish Count Radolf, by the end of the year.[132]

Saxon resistance and reprisal

[edit]In summer 782, Widukind returned from Denmark to attack the Frankish positions in Saxony.[133] He defeated a Frankish army, possibly due to rivalry among the Frankish counts leading it.[134] Charlemagne came to Verden after learning of the defeat, but Widukind fled before his arrival. Charlemagne summoned the Saxon magnates to an assembly and compelled them to turn prisoners over to him, since he regarded their previous acts as treachery. The annals record that Charlemagne had 4,500 Saxon prisoners beheaded in the massacre of Verden.[135] Fried writes, "Although this figure may be exaggerated, the basic truth of the event is not in doubt",[136] and Alessandro Barbero calls it "perhaps the greatest stain on his reputation."[137] Charlemagne issued the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, probably in the immediate aftermath of (or as a precursor of) the massacre.[138] With a harsh set of laws which included the death penalty for pagan practices, the Capitulatio "constituted a program for the forced conversion of the Saxons"[139] and was "aimed ... at suppressing Saxon identity".[140]

Charlemagne's focus for the next several years would be on his attempt to complete the subjugation of the Saxons. Concentrating first in Westphalia in 783, he pushed into Thuringia in 784 as his son Charles the Younger continued operations in the west. At each stage of the campaigns, the Frankish armies seized wealth and carried Saxon captives into slavery.[141] Unusually, Charlemagne campaigned through the winter instead of resting his army.[142] By 785 he had suppressed the Saxon resistance and completely commanded Westphalia. That summer, he met Widukind and persuaded him to end his resistance. Widukind agreed to be baptised with Charlemagne as his godfather, ending this phase of the Saxon Wars.[143]

Benevento, Bavaria, and Pepin's revolt

[edit]Charlemagne travelled to Italy in 786, arriving by Christmas. Aiming to extend his influence further into southern Italy, he marched into the Duchy of Benevento.[144] Duke Arechis fled to a fortified position at Salerno before offering Charlemagne his fealty. Charlemagne accepted his submission and hostages, who included Arechis's son Grimoald.[145] In Italy, Charlemagne also met with envoys from Constantinople. Empress Irene had called the 787 Second Council of Nicaea but did not inform Charlemagne or invite any Frankish bishops. Charlemagne, probably in reaction to the perceived slight of the exclusion, broke the betrothal of Rotrude and Constantine VI.[146]

After Charlemagne left Italy, Arechis sent envoys to Irene to offer an alliance; he suggested that she send a Byzantine army with Adalgis, the exiled son of Desiderus, to remove the Franks from power in Lombardy.[147] Before his plans could be finalised, Aldechis and his elder son Romuald died of illness within weeks of each other.[148] Charlemagne sent Grimoald back to Benevento to serve as duke and return it to Frankish suzerainty.[149] The Byzantine army invaded but were repulsed by the Frankish and Lombard forces.[150]

As affairs were being settled in Italy, Charlemagne turned his attention to Bavaria. Bavaria was ruled by Duke Tassilo, Charlemagne's first cousin, who had been installed by Pepin the Short in 748.[151] Tassilo's sons were also grandsons of Desiderius and thus were a potential threat to Charlemagne's rule in Lombardy.[152] The neighbouring rulers had a growing rivalry throughout their reigns, but they had sworn an oath of peace in 781.[153] In 784 Rotpert (Charlemagne's viceroy in Italy) accused Tassilo of conspiring with Widukind and unsuccessfully attacked the Bavarian city of Bolzano.[154] Charlemagne gathered his forces to prepare for an invasion of Bavaria in 787. Dividing the army, the Franks launched a three-pronged attack. Quickly realizing his poor position, Tassilo agreed to surrender and recognise Charlemagne as his overlord.[155] The following year, Tassilo was accused of plotting with the Avars to attack Charlemagne. He was deposed and sent to a monastery, and Charlemagne absorbed Bavaria into his kingdom.[156] Charlemagne spent the next few years based in Regensburg, largely focused on consolidating his rule of Bavaria and warring against the Avars.[157] Successful campaigns against them were launched from Bavaria and Italy in 788,[158] and Charlemagne led campaigns in 791 and 792.[159]

Charlemagne gave Charles the Younger rule of Maine in Neustria in 789, leaving Pepin the Hunchback his only son without lands.[160] His relationship with Himiltrude was now apparently seen as illegitimate at his court, and Pepin was sidelined from the succession.[161] In 792, as his father and brothers were gathered in Regensburg, Pepin conspired with Bavarian nobles to assassinate them and install himself as king. The plot was discovered and revealed to Charlemagne before it could proceed; Pepin was sent to a monastery, and many of his co-conspirators were executed.[162]

The early 790s saw a marked focus on ecclesiastical affairs by Charlemagne. He summoned a council in Regensburg in 792 to address the theological controversy over the adoptionism doctrine in the Spanish church and to formulate a response to the Second Council of Nicea.[163] The council condemned adoptionism as heresy and led to the production of the Libri Carolini, a detailed argument against Nicea's canons.[164] In 794 Charlemagne called another council in Frankfurt.[165] The council confirmed Regensburg's positions on adoptionism and Nicea, recognised the deposition of Tassilo, set grain prices, reformed Frankish coinage, forbade abbesses from blessing men, and endorsed prayer in vernacular languages.[166] Soon after the council, Fastrada fell ill and died;[167] Charlemagne married the Alamannian noblewoman Luitgard shortly afterwards.[168][169]

Continued wars with the Saxons and Avars

[edit]Charlemagne gathered an army after the council of Frankfurt as Saxon resistance continued, beginning a series of annual campaigns which lasted through 799.[170] The campaigns of the 790s were even more destructive than those of earlier decades, with the annal writers frequently noting Charlemagne "burning", "ravaging", "devastating", and "laying waste" the Saxon lands.[171] Charlemagne forcibly removed a large number of Saxons to Francia, installing Frankish elites and soldiers in their place.[172] His extended wars in Saxony led to his establishing his court in Aachen, which had easy access to the frontier. He built a large palace there, including a chapel which is now part of the Aachen Cathedral.[173] Einhard joined the court at that time.[174] Pepin of Italy (Carloman) engaged in further wars against the Avars in the south, which led to the collapse of their kingdom and the eastward expansion of Frankish rule.[175]

Charlemagne also worked to expand his influence through diplomatic means during the 790s wars, focusing on the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Britain. Charles the Younger proposed a marriage pact with the daughter of King Offa of Mercia, but Offa insisted that Charlemagne's daughter Bertha also be given as a bride for his son.[176] Charlemagne refused the arrangement, and the marriage did not take place.[177] Charlemagne and Offa entered into a formal peace in 796, protecting trade and securing the rights of English pilgrims to pass through Francia on their way to Rome.[178] Charlemagne was also the host and protector of several deposed English rulers who were later restored: Eadbehrt of Kent, Ecgberht, King of Wessex, and Eardwulf of Northumbria.[179][180] Nelson writes that Charlemagne treated the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms "like satellite states," establishing direct relations with English bishops.[181] Charlemagne also forged an alliance with Alfonso II of Asturias, although Einhard calls Alfonso his "dependent".[182] Following his sack of Lisbon in 798, Alfonso sent Charlemagne trophies of his victory, including armour, mules and prisoners.[183]

Reign as emperor

[edit]Coronation

[edit]After Leo III became pope in 795, he faced political opposition. His enemies accused him of a number of crimes and physically attacked him in April 799, attempting to remove his eyes and tongue.[184] Leo escaped and fled north to seek Charlemagne's help.[185] Charlemagne continued his campaign against the Saxons before breaking off to meet Leo at Paderborn in September.[186][187] Hearing evidence from the pope and his enemies, he sent Leo back to Rome with royal legates who were instructed to reinstate the pope and conduct a further investigation.[188] In August 799 Charlemagne made plans to go to Rome after an extensive tour of his lands in Neustria.[188][189] Charlemagne met Leo in November near Mentana at the 12th milestone outside Rome, the traditional location where Roman emperors began their formal entry into the city.[189] Charlemagne presided over an assembly to hear the charges but believed that no one could sit in judgment of the pope. Leo swore an oath on 23 December, declaring his innocence of all charges.[190] At mass in St. Peter's Basilica on Christmas Day 800, Leo proclaimed Charlemagne "emperor of the Romans" (Imperator Romanorum) and crowned him.[f] Charlemagne was the first reigning emperor in the west since the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476.[192] Charles the Younger was anointed king by Leo at the same time.[193]

Historians differ about the intentions of the imperial coronation, the extent to which Charlemagne was aware of it or participated in its planning, and the significance of the events for those present and for Charlemagne's reign.[186] Contemporary Frankish and papal sources differ in their emphasis on, and representation of, events.[194] Einhard writes that Charlemagne would not have entered the church if he knew about the pope's plan; modern historians have regarded his report as truthful or rejected it as a literary device demonstrating Charlemagne's humility.[195] Collins says that the actions surrounding the coronation indicate that it was planned by Charlemagne as early as his meeting with Leo in 799,[196] and Fried writes that Charlemagne planned to adopt the title of emperor by 798 "at the latest."[197] During the years before the coronation, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin referred to his realm as an Imperium Christianum ("Christian Empire") in which "just as the inhabitants of the Roman Empire had been united by a common Roman citizenship", the new empire would be united by a common Christian faith.[198] This is the view of Henri Pirenne, who says that "Charles was the Emperor of the ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church".[199]

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire remained a significant contemporary power in European politics for Leo and Charlemagne, especially in Italy. The Byzantines continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with their borders not far south of Rome. Empress Irene had seized the throne from her son Constantine VI in 797, deposing and blinding him.[200] Irene, the first Byzantine empress, faced opposition in Constantinople because of her gender and her means of accession.[201] One of the earliest narrative sources for the coronation, the Annals of Lorsch, present a female ruler in Constantinople as a vacancy in the imperial title which justified Leo's coronation of Charlemagne.[202] Pirenne disagrees, saying the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople."[203] Leo's main motivations may have been the desire to increase his standing after his political difficulties, placing himself as a power broker and securing Charlemagne as a powerful ally and protector.[204] The Byzantine Empire's lack of ability to influence events in Italy and support the papacy were also important to Leo's position.[204] According to the Royal Frankish Annals, Leo prostrated himself before Charlemagne after crowning him (an act of submission standard in Roman coronation rituals from the time of Diocletian). This account presents Leo not as Charlemagne's superior, but as the agent of the Roman people who acclaimed Charlemagne as emperor.[205]

Historian Henry Mayr-Harting claims that the assumption of the imperial title by Charlemagne was an effort to incorporate the Saxons into the Frankish realm, since they did not have a native tradition of kingship.[206] However, Costambeys et al. note in The Carolingian World "since Saxony had not been in the Roman empire it is hard to see on what basis an emperor would have been any more welcomed."[204] These authors write that the decision to take the title of emperor was aimed at furthering Charlemagne's influence in Italy, as an appeal to traditional authority recognised by Italian elites within and (especially) outside his control.[204]

Collins writes that becoming emperor gave Charlemagne "the right to try to impose his rule over the whole of [Italy]", considering this a motivation for the coronation.[207] He notes the "element of political and military risk"[207] inherent in the affair due to the opposition of the Byzantine Empire and potential opposition from the Frankish elite, as the imperial title could draw him further into Mediterranean politics.[208] Collins sees several of Charlemagne's actions as attempts to ensure that his new title had a distinctly-Frankish context.[209]

Charlemagne's coronation led to a centuries-long ideological conflict between his successors and Constantinople known as the problem of two emperors,[g] which could be seen as a rejection or usurpation of the Byzantine emperors' claim to be the universal, preeminent rulers of Christendom.[210] Historian James Muldoon writes that Charlemagne may have had a more limited view of his role, seeing the title as representing dominion over lands he already ruled.[211] However, the title of emperor gave Charlemagne enhanced prestige and ideological authority.[212][213] He immediately incorporated his new title into documents he issued, adopting the formula "Charles, most serene augustus, crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the Roman empire, and who is by the mercy of God king of the Franks and the Lombards"[h] instead of the earlier form "Charles, by the grace of God king of the Franks and Lombards and patrician of the Romans."[i][3] Leo acclaimed Charlemagne as "emperor of the Romans" during the coronation, but Charlemagne never used this title.[214] The avoidance of the specific claim of being a "Roman emperor", as opposed to the more neutral "emperor governing the Roman empire", may have been to improve relations with the Byzantines.[215][216] This formulation (with the continuation of his earlier royal titles) may also represent a view of his role as emperor as being the ruler of the people of the city of Rome, as he was of the Franks and the Lombards.[215][217]

Governing the empire

[edit]

Charlemagne left Italy in the summer of 801 after adjudicating several ecclesiastical disputes in Rome and experiencing an earthquake in Spoleto.[218] He never returned to the city.[212] Continuing trends and a ruling style established in the 790s,[219] Charlemagne's reign from 801 onward is a "distinct phase"[220] characterised by more sedentary rule from Aachen.[212] Although conflict continued until the end of his reign, the relative peace of the imperial period allowed for attention on internal governance. The Franks continued to wage war, though these wars were defending and securing the empire's frontiers,[221][222] and Charlemagne rarely led armies personally.[223] A significant expansion of the Spanish March was achieved with a series of campaigns by Louis against the Emirate of Cordoba, culminating in the 801 capture of Barcelona.[224]

The 802 Capitulare missorum generale was an expansive piece of legislation, with provisions governing the conduct of royal officials and requiring that all free men take an oath of loyalty to Charlemagne.[225][226] The capitulary reformed the institution of the missi dominici, officials who would now be assigned in pairs (a cleric and a lay aristocrat) to administer justice and oversee governance in defined territories.[227] The emperor also ordered the revision of the Lombard and Frankish legal codes.[228]

In addition to the missi, Charlemagne also ruled parts of the empire with his sons as sub-kings.[229] Although Pepin and Louis had some authority as kings in Italy and Aquitaine, Charlemagne had the ultimate authority and directly intervened.[230] Charles, their elder brother, had been given lands in Neustria in 789 or 790 and made a king in 800.[231]

The 806 charter Divisio Regnorum (Division of the Realm) set the terms of Charlemagne's succession.[232] Charles, as his eldest son in good favour, was given the largest share of the inheritance: rule of Francia, Saxony, Nordgau, and parts of Alemannia. The two younger sons were confirmed in their kingdoms and gained additional territories; most of Bavaria and Alemmannia was given to Pepin, and Provence, Septimania, and parts of Burgundy were given to Louis.[233] Charlemagne did not address the inheritance of the imperial title.[231] The Divisio also provided that if any of the brothers predeceased Charlemagne, their sons would inherit their share; peace was urged among his descendants.[234]

Conflict and diplomacy with the east

[edit]

After his coronation, Charlemagne sought recognition of his imperial title from Constantinople.[235] Several delegations were exchanged between Charlemagne and Irene in 802 and 803. According to the contemporary Byzantine chronicler Thophanes, Charlemagne made an offer of marriage to Irene which she was close to accepting.[236] Irene was deposed and replaced by Nikephoros I, who was unwilling to recognise Charlemagne as emperor.[236] The two empires conflicted over control of the Adriatic Sea (especially Istria and Veneto) several times during Nikephoros' reign. Charlemagne sent envoys to Constantinople in 810 to make peace, giving up his claims to Veneto. Nikephoros died in battle before the envoys could leave Constantinople, but his successor Michael I confirmed the peace, sending his own envoys to Aachen to recognise Charlemagne as emperor.[237] Charlemagne soon issued the first Frankish coins bearing his imperial title, although papal coins minted in Rome had used the title as early as 800.[238]

He sent envoys and initiated diplomatic contact with the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid during the 790s, due to their mutual interest in Spanish affairs.[239] As an early sign of friendship, Charlemagne requested an elephant as a gift from Harun. Harun later provided an elephant named Abul-Abbas, which arrived at Aachen in 802.[240] Harun also sought to undermine Charlemagne's relations with the Byzantines, with whom he was at war. As part of his outreach, Harun gave Charlemagne nominal rule of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and other gifts.[241] According to Einhard, Charlemagne "zealously strove to make friendships with kings beyond the seas" in order "that he might get some help and relief to the Christians living under their rule." A surviving administrative document, the Basel roll, shows the work done by his agents in Palestine in furtherance of this goal.[242][j]

Harun's death lead to a succession crisis, and under his successors churches and synagogues were destroyed in the caliphate.[243] Unable to intervene directly, Charlemagne sent specially-minted coins and arms to the eastern Christians to defend and restore their churches and monasteries. The coins with their inscriptions were also an important tool of imperial propaganda.[244] Fried writes that deteriorating relations with Baghdad after Harun's death may have been the impetus for renewed negotiations with Constantinople which led to Charlemagne's peace with Michael in 811.[245]

As emperor, Charlemagne became involved in a religious dispute between Eastern and Western Christians over the recitation of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, the fundamental statement of orthodox Christian belief. The original text of the creed, adopted at the Council of Constantinople, professed that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father. A tradition developed in Western Europe that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father "and the Son", inserting the Latin term filioque into the creed.[246] The difference did not cause significant conflict until 807, when Frankish monks in Bethlehem were denounced as heretics by a Greek monk for using the filioque form.[246] The Frankish monks appealed the dispute to Rome, where Pope Leo affirmed the text of the creed omitting the phrase and passed the report on to Charlemagne.[247] Charlemagne summoned a council at Aachen in 809 which defended the use of filioque and sent the decision to Rome. Leo said that the Franks could maintain their tradition but asserted that the canonical creed did not include filioque.[248] Leo commissioned two silver shields with the creed in Latin and Greek (omitting the filioque), which he hung in St. Peter's Basilica.[246][249] Another product of the 809 Aachen council was the Handbook of 809, an illustrated calendrical and astronomical compendium.[250]

Wars with the Danes

[edit]

Scandinavia had been brought into contact with the Frankish world through Charlemagne's wars with the Saxons.[251] Raids on Charlemagne's lands by the Danes began around 800.[252] Charlemagne engaged in his final campaign in Saxony in 804, seizing Saxon territory east of the Elbe, removing its Saxon population, and giving the land to his Obotrite allies.[253] Danish King Gudfred, uneasy at the extension of Frankish power, offered to meet with Charlemagne to arrange peace and (possibly) hand over Saxons who had fled to him;[252][254] the talks were unsuccessful.[254]

The northern frontier was quiet until 808, when Gudfred and some allied Slavic tribes led an incursion into the Obotrite lands and extracted tribute from over half the territory.[255][252] Charles the Younger led an army across the Elbe in response, but he only attacked some of Gudfred's Slavic allies.[256] Gudfred again attempted diplomatic overtures in 809, but no peace was apparently made.[257] Danish pirates raided Frisia in 810, although it is uncertain if they were connected to Gudfred.[258] Charlemagne sent an army to secure Frisia while he led a force against Gudfred, who had reportedly challenged the emperor to face him in battle.[223][258] Gudfred was murdered by two of his own men before Charlemagne's arrival.[222] Gudfred's successor Hemming immediately sued for peace, and a commission led by Charlemagne's cousin Wala reached a settlement with the Danes in 811.[223] The Danes did not pose a threat for the remainder of Charlemagne's reign, but the effects of this war and their earlier expansion in Saxony helped set the stage for the intense Viking raids across Europe later in the 9th century.[259][260]

Final years and death

[edit]

The Carolingian dynasty experienced several losses in 810 and 811, when Charlemagne's sister Gisela, his daughter Rotrude, and his sons Pepin the Hunchback, Pepin of Italy, and Charles the Younger died.[261] The deaths of Charles and Pepin of Italy left Charlemagne's earlier plans for succession in disarray. He declared Pepin of Italy's son Bernard ruler of Italy and made his own only surviving son, Louis, heir to the rest of the empire.[262] Charlemagne also made a his will detailing the disposal of his property at his death, with bequests to the church, his children, and his grandchildren.[263] Einhard (possibly relying on tropes from Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars) says that Charlemagne viewed the deaths of his family members, his fall from a horse, astronomical phenomena, and the collapse of part of the palace in his last years as signs of his impending death.[264] Charlemagne continued to govern with energy during his final year, ordering bishops to assemble in five ecclesiastical councils.[265] These culminated in a large assembly at Aachen, where Charlemagne crowned Louis as his co-emperor and Bernard as king in a ceremony on 11 September 813.[266]

Charlemagne became ill in the autumn of 813 and spent his last months praying, fasting, and studying the gospels.[264] He developed pleurisy and was bedridden for seven days before dying on the morning of 28 January 814.[267] Thegan, a biographer of Louis, records the emperor's last words as "Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit".[268] Charlemagne's body was prepared and buried in the chapel at Aachen by his daughters and palace officials that day.[269] Louis arrived at Aachen 30 days after his father's death, taking charge of the palace and the empire.[270] Charlemagne's remains were exhumed by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in 1165 and reinterred by Frederick II in 1215.[271]

Legacy

[edit]Political legacy

[edit]

The stability and peace of Charlemagne's reign did not long outlive him. Louis' reign was marked by strife, including a number of rebellions by his sons. After Louis' death, the empire was divided among his sons into West, East, and Middle Francia by the Treaty of Verdun.[272] Middle Francia was divided several more times over the course of subsequent generations.[273] Carolingians would rule – with some interruptions – in East Francia (later the Kingdom of Germany) until 911[192] and in West Francia (which would become France) until 987.[274] After 887 the imperial title was held sporadically by a series of non-dynastic Italian rulers[275] before it lapsed in 924.[276] East Frankish King Otto the Great conquered Italy and was crowned emperor in 962.[277] By this time, the eastern and western parts of Charlemagne's former empire had already developed distinct languages and cultures.[278] Otto founded (or re-established) the Holy Roman Empire, which would last until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.[279]

According to historian Jennifer Davis, Charlemagne "invented medieval rulership," and his influence can be seen at least into the 19th century.[280] Charlemagne is often known as "the father of Europe" because of the influence of his reign and the legacy he left across the large area of the continent.[281] The political structures he established remained in place through his Carolingian successors and continued to exert influence into the 11th century.[282]

Charlemagne was an ancestor of several European ruling houses, including the Capetian dynasty,[k] the Ottonian dynasty,[l] the House of Luxembourg,[m] and the House of Ivrea.[n] The Ottonians and Capetians, direct successors of the Carolingans, drew on the legacy of Charlemagne to bolster their legitimacy and prestige; the Ottonians and their successors held their German coronations in Aachen through the Middle Ages.[287] The marriage of Philip II of France to Isabella of Hainault (a direct descendant of Charlemagne) was seen as a sign of increased legitimacy for their son Louis VIII, and the French kings' association with Charlemagne's legacy was stressed until the monarchy's end.[288] German and French rulers such as Frederick Barbarossa and Napoleon cited the influence of Charlemagne and associated themselves with him.[289] Both German and French monarchs considered themselves successors of Charlemagne, enumerating him as "Charles I" in their regnal lists.[290]

During the Second World War, Aachen's historical association with Charlemagne gave it symbolic importance for both Germans and Americans alike.[291][292] For Germans, the city represented the heart of the Carolingian legacy—Charlemagne made Aachen the political centre of his realm—and it later served as the customary coronation city of the German kings of the Holy Roman Empire. For Americans, its capture carried weight as it marked both the first major German city taken by Allied forces and a symbolic challenge to Hitler's emphasis on defending a city so closely tied to Charlemagne.[293][294] As a result, Hitler insisted on a staunch defense of Aachen, which led to a protracted and destructive battle in October 1944.[295]

Since 1949 Aachen has awarded an international prize (the Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen) in honour of Charlemagne. It is awarded annually to those who promote European unity.[289] Recipients of the prize include Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi (founder of the pan-European movement), Alcide De Gasperi, and Winston Churchill.[296]

Carolingian Renaissance

[edit]Contacts with the wider Mediterranean world through Spain and Italy, the influx of foreign scholars at court, and the relative stability and length of Charlemagne's reign led to a cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance.[297] Although the beginnings of this revival can be seen under his predecessors, Charles Martel and Pepin, Charlemagne took an active and direct role in shaping intellectual life which led to the revival's zenith.[298] Charlemagne promoted learning as a matter of policy and direct patronage, with the aim of creating a more effective clergy.[299] The Admonitio generalis and Epistola de litteris colendis outline his policies and aims for education.[300]

Intellectual life at court was dominated by Irish, Anglo-Saxon, Visigothic and Italian scholars, including Dungal of Bobbio, Alcuin of York, Theodulf of Orléans, and Peter of Pisa; Franks such as Einhard and Angelbert also made substantial contributions.[301] Aside from the intellectual activity at the palace, Charlemagne promoted ecclesiastical schools and publicly funded schools for the children of the elite and future clergy.[302] Students learned basic Latin literacy and grammar, arithmetic, and other subjects of the medieval liberal arts.[303] From their education, it was expected that even rural priests could provide their parishioners with basic instruction in religious matters and (possibly) the literacy required for worship.[304] Latin was standardised and its use brought into territories well beyond the former Roman Empire, forming a second language community of speakers and writers and sustaining Latin creativity in the Middle Ages.[305]

Carolingian authors produced extensive works, including legal treatises, histories, poetry, and religious texts.[306][307] Scriptoria in monasteries and cathedrals focused on copying new and old works, producing an estimated 90,000 manuscripts during the 9th century.[308] The Carolingian minuscule script was developed and popularised in medieval copying, influencing Renaissance and modern typefaces.[309] Scholar John J. Contreni considers the educational and learning revival under Charlemagne and his successors "one of the most durable and resilient elements of the Carolingian legacy".[309]

Memory and historiography

[edit]Charlemagne is a frequent subject and inspiration for medieval writers after his death. Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni, according to Fried, "can be said to have revived the defunct literary genre of the secular biography."[310] Einhard drew on classical sources such as Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, the orations of Cicero, and Tacitus' Agricola to frame his work's structure and style.[311] The Carolingian period also saw a revival of the mirrors for princes genre.[312] The author of the Latin poem Visio Karoli Magni, written c. 865, uses facts (apparently from Einhard) and his own observations on the decline of Charlemagne's family after their civil wars later in the 9th century as the bases of a visionary tale about Charles meeting a prophetic spectre in a dream.[313] Notker's Gesta Karoli Magni, written for Charlemagne's great-grandson Charles the Fat, presents moral anecdotes (exempla) to highlight the emperor's qualities as a ruler.[314]

Charlemagne grew over the centuries as a figure of myth and emulation; Matthias Becher writes that over 1,000 legends are recorded about him, far outstripping subsequent emperors and kings.[315] Later medieval writers depict Charlemagne as a crusader and Christian warrior.[315][316] Charlemagne is the main figure of the medieval literary cycle known as the Matter of France. Works in this cycle, which originated during the Crusades, centre on characterisations of the emperor as a leader of Christian knights in wars against Muslims. The cycle includes chansons de geste (epic poems) such as the Song of Roland and chronicles such as the Historia Caroli Magni, also known as the (Pseudo-)Turpin Chronicle.[317] Charlemagne is depicted as one of the Nine Worthies, a fixture in medieval literature and art as an exemplar of a Christian king.[318] Despite his central role in these legends, author Thomas Bulfinch notes "romancers represent him as often weak and passionate, the victim of treacherous counsellors, and at the mercy of turbulent barons, on whose prowess he depends for the maintenance of his throne."[319]

Attention to Charlemagne became more scholarly in the early modern period as Eindhard's Vita and other sources began to be published.[320] Political philosophers debated his legacy; Montesquieu viewed him as the first constitutional monarch and protector of freemen, but Voltaire saw him as a despotic ruler and representative of the medieval period as a Dark Age.[321] As early as the 16th century, debate between German and French writers began about Charlemagne's "nationality".[322] These contrasting portraits—a French Charlemagne versus a German Karl der Große—became especially pronounced during the 19th century with Napoleon's use of Charlemagne's legacy and the rise of German nationalism.[316][323] German historiography and popular perception focused on the Massacre of Verden, emphasised with Charlemagne as the "butcher" of the Germanic Saxons or downplayed as an unfortunate part of the legacy of a great German ruler.[324] Propaganda in Nazi Germany initially portrayed Charlemagne as an enemy of Germany, a French ruler who worked to take away the freedom and native religion of the German people.[325] This quickly shifted as Hitler endorsed a portrait of Charlemagne as a great unifier of disparate German tribes into a common nation, allowing Hitler to co-opt Charlemagne's legacy as an ideological model for his expansionist policies.[326]

Historiography after World War II focused on Charlemagne as "the father of Europe" rather than a nationalistic figure,[327] a view first advanced during the 19th century by German romantic philosopher Friedrich Schlegel.[316] This view has led to Charlemagne's adoption as a political symbol of European integration.[328] Modern historians increasingly place Charlemagne in the context of the wider Mediterranean world, following the work of Henri Pirenne.[329]

Religious influence and veneration

[edit]

Charlemagne gave much attention to religious and ecclesiastical affairs, holding 23 synods during his reign. His synods were called to address specific issues at particular times but generally dealt with church administration and organisation, education of the clergy, and the proper forms of liturgy and worship.[330] Charlemagne used the Christian faith as a unifying factor in the realm and, in turn, worked to impose unity on the church.[331][332] He implemented an edited version of the Dionysio-Hadriana book of canon law acquired from Pope Adrian, required use of the Rule of St. Benedict in monasteries throughout the empire, and promoted a standardised liturgy adapted from the rites of the Roman Church to conform with Frankish practices.[333] Carolingian policies promoting unity did not eliminate the diverse practices throughout the empire, but created a shared ecclesiastical identity—according to Rosamond McKitterick, "unison, not unity."[334]

The condition of all his subjects as a "Christian people" was an important concern.[335] Charlemagne's policies encouraged preaching to the laity, particularly in vernacular languages they would understand.[336] He believed it essential to be able to recite the Lord's Prayer and the Apostles' Creed, and he made efforts to ensure that the clergy taught them and other basics of Christian morality.[337]

Thomas F. X. Noble writes that the efforts of Charlemagne and his successors to standardise Christian doctrine and practices and harmonise Frankish practices were essential steps in the development of Christianity in Europe, and the Roman Catholic or Latin Church "as a historical phenomenon, not as a theological or ecclesiological one, is a Carolingian construction."[338][339] He says that the medieval European concept of Christendom as an overarching community of Western Christians, rather than a collection of local traditions, is the result of Carolingian policies and ideology.[340] Charlemagne's doctrinal policies promoting the use of filioque and opposing the Second Council of Nicea were key steps in the growing divide between Western and Eastern Christianity.[341]

Emperor Otto III attempted to have Charlemagne canonised in 1000.[342] In 1165 Barbarossa persuaded Antipope Paschal III to elevate Charlemagne to sainthood.[342] Since Paschal's acts were not considered valid, Charlemagne was not recognised as a saint by the Holy See.[343] Despite this lack of official recognition, his cult was observed in Aachen, Reims, Frankfurt, Zurich and Regensburg, and he has been venerated in France since the reign of Charles V.[344]

Charlemagne also drew attention from figures of the Protestant Reformation, with Martin Luther criticising his apparent subjugation to the papacy by accepting his coronation from Leo.[321] John Calvin and other Protestant thinkers viewed him as a forerunner of the Reformation, noting the Libri Carolini's condemnation of the worship of images and relics and conflicts by Charlemagne and his successors with the temporal power of the popes.[343]

Wives, concubines, and children

[edit]|

Wives and their children[345][346]

|

Concubines and their children[345][346]

|

Charlemagne had at least 20 children with his wives and other partners.[345][346] After the death of Luitgard in 800, he did not remarry but had children with unmarried partners.[352] He was determined that all his children, including his daughters, should receive an education in the liberal arts. His children were taught in accordance with their aristocratic status, which included training in riding and weaponry for his sons, and embroidery, spinning and weaving for his daughters.[353]

McKitterick writes that Charlemagne exercised "a remarkable degree of patriarchal control ... over his progeny," noting that only a handful of his children and grandchildren were raised outside his court.[354] Pepin of Italy and Louis reigned as kings from childhood and lived at their courts.[127] Careers in the church were arranged for his illegitimate sons.[355] His daughters were residents at court or at Chelles Abbey (where Charlemagne's sister was abbess), and those at court may have fulfilled the duties of queen after 800.[356]

Louis and Pepin of Italy married and had children during their father's lifetime, and Charlemagne brought Pepin's daughters into his household after Pepin's death.[357] None of Charlemagne's daughters married, although several had children with unmarried partners. Bertha had two sons, Nithard and Hartnid, with Charlemagne's courtier Angilbert; Rotrude had a son named Louis, possibly with Count Rorgon; and Hiltrude had a son named Richbod, possibly with a count named Richwin.[358] The Divisio Regnorum issued by Charlemagne in 806 provided that his legitimate daughters be allowed to marry or become nuns after his death. Theodrada entered a convent, but the decisions of his other daughters are unknown.[359]

Appearance and iconography

[edit]Einhard gives a first-hand description of Charlemagne's appearance later in life:[360]

He was heavily built, sturdy, and of considerable stature, although not exceptionally so, since his height was seven times the length of his own foot. He had a round head, large and lively eyes, a slightly larger nose than usual, white but still attractive hair, a bright and cheerful expression, a short and fat neck, and he enjoyed good health, except for the fevers that affected him in the last few years of his life.

Charlemagne's tomb was opened in 1861 by scientists who reconstructed his skeleton and measured it at 1.92 metres (6 ft 4 in) in length, roughly equivalent to Einhard's measurement.[361] A 2010 estimate of his height from an X-ray and CT scan of his tibia was 1.84 metres (6 ft 0 in); this puts him in the 99th percentile of height for his period, given that average male height of his time was 1.69 metres (5 ft 7 in). The width of the bone suggested that he was slim.[362]

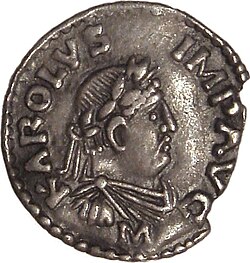

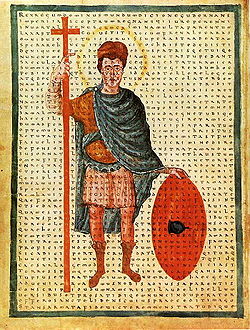

Charlemagne wore his hair short, abandoning the Merovingian tradition of long-haired monarchs.[363] He had a moustache (possibly imitating King Theodoric the Great), in contrast with the bearded Merovingian kings;[364] future Carolingian monarchs adopted this style.[365] Paul Dutton notes the ubiquitous crown in portraits of Charlemagne and other Carolingian rulers, replacing the earlier Merovingian long hair.[366] A 9th-century statuette depicts Charlemagne or his grandson Charles the Bald[p] and shows the subject as moustachioed with short hair;[368] this also appears on contemporary coinage.[371]

By the 12th century, Charlemagne is described as bearded rather than moustachioed in literary sources such as the Song of Roland, the Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle, and other works in Latin, French, and German.[372] The Pseudo-Turpin uniquely says that his hair was brown.[373] Later art and iconography of Charlemagne generally depicts him in a later medieval style as bearded with longer hair.[374]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Alternative birth years for Charlemagne include 742 and 747. There has been scholarly debate over this topic, see § Birth and early life. For full treatment of the debate, see Nelson 2019, pp. 28–29. See further Karl Ferdinand Werner, Das Geburtsdatum Karls des Großen, in Francia 1, 1973, pp. 115–157 (online Archived 17 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine);

Matthias Becher: Neue Überlegungen zum Geburtsdatum Karls des Großen, in: Francia 19/1, 1992, pp. 37–60 (online Archived 17 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine) - ^ For more on the polyglot world of Charlemagne and that of both his immediate predecessors, contemporaries, and successors concerning charters and mandates, see: Roberts, Edward, and Francesca Tinti. "Signalling Language Choice in Anglo-Saxon and Frankish Charters, c.700–c.900". In The Languages of Early Medieval Charters (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2020) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004432338_007.

- ^ "At 747 the scribe had written: 'Et ipso anno fuit natus Karolus rex' ('and in that year, King Charles was born')."[26]

- ^ Historian Johannes Fried writes that "Comparisons with other images allow us to interpret it as a sketch of an ancient emperor or king, or even of Charlemagne himself. However sketchy and unaccomplished the drawing is, its message and its moral could not be clearer: the ruler appears here as a powerful protector, guarding the Church with his weapons and—as the following text emphasises—restoring it according to the dictates of the faith and the Church Fathers in preparation for the impending end time."[41]

- ^ Charlemagne's third son (Carloman) was also born in 776, based on the four-year-old's 780 baptism in Pavia.[115]

- ^ The Latin title imperator, meaning "commander", used to denote successful generals in ancient Rome, but eventually came to denote the position of Augustus and his successors.[191] In German, the title was rendered as kaiser, after Caesar. In Greek, it was rendered as autokrator and used alongside the traditional title of basileus. For a discussion of Charlemagne's title and Constantinople's reaction, see Sarti 2024, pp. 7–39.

- ^ German: Zweikaiserproblem, "two-emperors problem"

- ^ Latin: Karolus serenissimus augustus a deo coronatus magnus pacificus imperator Romanum gubernans imperium, qui et per misercordiam dei rex francorum atque langobardorum

- ^ Latin: Carolus gratia dei rex francorum et langobardorum ac patricius Romanorum

- ^ For more on the Basel roll, see McCormick 2011.

- ^ Through Beatrice of Vermandois, great-great granddaughter of Pepin of Italy and grandmother of Hugh Capet,[283]

- ^ Through Hedwiga, great-great granddaughter of Louis the Pious and mother of Henry the Fowler[284]

- ^ Through Albert II, Count of Namur, great-grandson of Louis IV of France and great-great-grandfather of Henry the Blind[285]

- ^ Berengar II of Italy was a great-great-great grandson of Louis the Pious.[286] The House of Ivrea later came to rule Spain and intermarried with the Habsburgs and the royal families of Portugal.

- ^ The nature of Himiltrude's relationship to Charlemagne is uncertain. A 770 letter by Pope Stephen III describes both Carloman and Charlemagne "by [God's] will and decision...joined in lawful marriage...[with] wives of great beauty from the same fatherland as yourselves."[347] Stephen wrote this in the context of attempting to dissuade either king from entering into a marriage alliance with Desiderius.[79] By 784, at Charlemagne's court, Paul the Deacon wrote that their son Pepin was born "before legal marriage", but whether he means Charles and Himiltrude were never married, were joined in a non-canonical marriage or friedelehe, or if they married after Pepin was born is unclear.[78] Roger Collins,[348] Johannes Fried,[349] and Janet Nelson[350] all portray Himiltrude as a wife of Charlemagne in some capacity. Fried also dates the beginning of their relationship to 763 or even earlier.[351]

- ^ Janet Nelson considers it a depiction of Charlemagne;[367] Paul Dutton says that it was "long thought to depict Charlemagne and now attributed by most to Charles the Bald,"[368] and Johannes Fried presents both as possibilities[369] but considers it "highly contentious."[370]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Riché 1993, pp. 130–132.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 2, 68.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 116.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 529.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 413.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Becher 2005, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Nonn 2008, p. 575.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 270, 274–275.

- ^ Heather 2009, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Frassetto 2003, p. 292.

- ^ Frassetto 2003, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 271.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Nelson 2019, p. 29.

- ^ a b Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 15.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Becher 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 28–28.

- ^ Hägermann 2011, p. xxx.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 350 n7.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 28.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Wilson, D. (2014). Charlemagne: Barbarian and Emperor, p.89, United Kingdom, Random House.

- ^ a b c d Nelson 2019, p. 68.

- ^ Hägermann 2011, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b Chambers & Wilkie 2014, p. 33.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Dutton 2016, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Dutton 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Dutton 2016, pp. 75–80.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 271.

- ^ Dutton 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Dutton 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 120.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 73.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 32.

- ^ a b Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 34.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 72.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 62.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 74.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 64.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 75.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 91.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 65.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 79.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 80.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 81.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 99.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 99, 101.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 101.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 84–85, 101.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 106.

- ^ Nelson 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 104–106.

- ^ a b Goffart 1986.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 84.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 109–110.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 99.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 116.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 117.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b c Nelson 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 133, 134.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 130.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 100.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 146.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 101.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 135–138.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 112.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Collins 1998, pp. 61–63.

- ^ a b c Collins 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 147.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 159.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 157.

- ^ a b Fried 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 166.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 167–170, 173.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 168, 172.

- ^ a b c d Nelson 2019, p. 181.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 175–179.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 173.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 182–186.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 186.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 191.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 203.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 205.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 193.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 193–195.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 126.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 46.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Barbero 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 197.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 55.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 228.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 225–226, 230.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 234.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 142.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 240.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 152.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 294.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 257.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 270.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 270, 274–275.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 285–287, 438.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 289–292.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 302.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 306–314.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 304.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 340, 377–379.

- ^ Riché 1993, p. 135.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 319–321.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 325–326, 329–331.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 356–359.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 340.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 326, 333.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 352, 400, 460.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 466.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 353.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Reuter 1985, p. 85.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 160.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 152.

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 115.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 143.

- ^ a b Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 161.

- ^ a b Collins 1998, p. 145.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 381.

- ^ Hornblower 2012, p. 728.

- ^ a b Heather 2009, p. 368.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 161, 163, 165.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 147.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 408.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Pirenne 2012, p. 233.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 361.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 370.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 384.

- ^ Pirenne 2012, p. 234n.

- ^ a b c d Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 167.

- ^ Muldoon 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Mayr-Harting 1996.

- ^ a b Collins 1998, p. 148.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 149.

- ^ Collins 1998, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Muldoon 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Muldoon 1999, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 168.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 382, 385.

- ^ a b Muldoon 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Sarti 2024, pp. 7–39.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 387–389.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 472.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 170.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 462.

- ^ a b c Collins 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Collins 1998, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 495–496.

- ^ Ganshof 1965.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 450–451.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 448–449.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 409, 411.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 410–415.

- ^ a b Collins 1998, p. 157.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 429.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 477.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 432–435.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 167–168.

- ^ a b Collins 1998, p. 153.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 458–459.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Dutton 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Dutton 2016, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 441.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 449–452.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 442.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 442–446.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 444.

- ^ a b c Nelson 2019, p. 449.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 449–450.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 452–453.

- ^ Sterk 1988.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 488–490.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 461.

- ^ a b c Collins 1998, p. 167.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 163.

- ^ a b Fried 2016, p. 462.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 462–463.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 459.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 168.

- ^ a b Fried 2016, p. 463.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 171.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 440, 453.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 468–470.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, pp. 480–481.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 478–480.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 476.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 514.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 481.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 482–483.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 483–484.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 520.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 379–381.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 394.

- ^ Riché 1993, p. 278.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 424–427.

- ^ Arnold 1997, p. 83.

- ^ Heather 2009, p. 369.

- ^ Scales 2012, pp. 155–182.

- ^ Davies 1996, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Davis 2015, p. 434.

- ^ Freeman 2017, p. 19.

- ^ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, pp. 407, 432.

- ^ Lewis 1977, pp. 246–247, n 94.

- ^ Jackman 2010, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Tanner 2004, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Bouchard 2010, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Fried 2016, p. 528.

- ^ Fried 2016, pp. 527–528.

- ^ a b Davis 2015, p. 433.

- ^ Williams 1885, pp. 446–47.

- ^ Chamberlin 2025, p. 475.