Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Anax (Greek: ἄναξ; from earlier ϝάναξ, wánax) is an ancient Greek word for "tribal chief, lord (military) leader".[1] It is one of the two Greek titles traditionally translated as "king", the other being basileus, and is inherited from Mycenaean Greece. It is notably used in Homeric Greek, e.g. for Agamemnon. The feminine form is anassa, "queen" (ἄνασσα, from wánassa, itself from *wánakt-ja).[2]

Homeric anax

[edit]Etymology

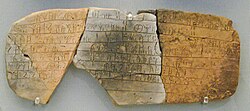

[edit]The word anax derives from the stem wanakt- (nominative *ϝάνακτς, genitive ϝάνακτος), and appears in Mycenaean Greek written in Linear B script as 𐀷𐀙𐀏, wa-na-ka,[1] and in the feminine form as 𐀷𐀙𐀭, wa-na-sa[3] (later ἄνασσα, ánassa). The digamma ϝ was pronounced /w/ and was dropped very early on, even before the adoption of the Phoenician alphabet, by eastern Greek dialects (e.g. Ionic Greek); other dialects retained the digamma until well after the classical era.

The Greek title has been compared[by whom?] to Sanskrit vanij, a word for "merchant", but in the Rigveda once used as a title of Indra in Rig Veda 5.45.6. The word could then be from Proto-Indo-European *wen-aǵ-, roughly "bringer of spoils" (compare the etymology of lord, "bread guardian"). However, Robert Beekes argues there is no convincing IE etymology and the term is probably from the pre-Greek substrate.

References

[edit]The word anax in the Iliad refers to Agamemnon (ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν, anax andrōn, i.e. "leader of men") and to Priam, high kings who exercise overlordship over other, presumably lesser, kings. This possible hierarchy of one anax exercising power over several local "basileis" probably hints to a proto-feudal political organization of Aegean civilizations. The Linear B adjective 𐀷𐀙𐀏𐀳𐀫, wa-na-ka-te-ro (wanákteros), "of [the household of] the king, royal",[4] and the Greek word ἀνάκτορον, anáktoron, "royal [dwelling], palace"[5] are derived from anax. Anax is also a ceremonial epithet of the god Zeus ("Zeus Anax") in his capacity as overlord of the Universe, including the rest of the gods. The meaning of basileus as "king" in Classical Greece is due to a shift in terminology during the Greek Dark Ages. In Mycenaean times, a *gʷasileus appears to be a lower-ranking official (in one instance a chief of a professional guild), while in Homer, anax is already an archaic title, most suited to legendary heroes and gods rather than for contemporary kings.

The word is found as an element in such names as Hipponax ("king of horses"), Anaxagoras ("king of the agora"), Pleistoanax ("king of the multitude"), Anaximander ("king of the estate"), Anaximenes ("enduring king"), Astyanax ("high king", "overlord of the city"), Anaktoria ("royal [woman]"), Iphiánassa ("mighty queen"), and many others. The archaic plural ánakes (ἄνακες, "Kings") was a common reference to the Dioskouroi, whose temple was usually called the Anakeion (ἀνάκειον) and their yearly religious festival the Anákeia (ἀνάκεια).

The words ánax and ánassa are occasionally used in Modern Greek as a deferential to royalty, whereas the word anáktoro[n] and its derivatives are commonly used with regard to palaces.

Mycenaean wánax

[edit]

During the Mediterranean Bronze Age, Mycenaean society was characterized by the creation of palaces and walled settlements. The wánax in Mycenaean social hierarchy is generally accepted to function as a king, though with various roles which also stretch outside of administrative function.[6] The term "wánax" is believed to have eventually transformed into the Homeric term "anax", having fallen out of use with the collapse of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age Collapse.[7] The Greek term for kingship would transfer to basileus, which is believed to have been a subservient title in Mycenaean times akin for chieftains and local leaders.[7][8]

Roles

[edit]The origin role of the wánax may be from warrior roots of migrating Indo-Europeans as a leadership role, eventually leading to the notion of kingship and the formal position and role of the wánax in Mycenaean times.[9] The wánax during Mycenaean times was at the apex of Mycenaean society, presiding over a centralized state administration with a strong hierarchical organization; a common formula in the Bronze Age Mediterranean and Near East. This is hierarchically likened to a king, and as such much of the duties of the wánax were related to duties of administration, warfare, diplomacy, economics and religion.

Administrative participation

[edit]Administratively, Mycenaean political divisions broadly unfolded into a hierarchical division of wánax (king) with a broader structure which existed around the wánax in the form of Mycenaean palatial authority and administration.[8] The wánax is also identified as the figure able to appoint individuals to rank within the administrative elite.[8] Much of this administrative body functioned as the limbs by which a wánax exercised authority and action, rather than directly partaking directly in every function of the state; with only two known inscription references on record of the wánax taking direct action within the internal administrative body.[6] However, much of the records available concerning the role of wánax deal with economic information due to the importance of such scribal records to Mycenaean states, but does not discredit the participation of the wánax directly in other facets of the state.[6] The wánax would also delegate lands to members of this palatial elite and other hierarchic officials depending on their role, such as with the telestai.[6][10] Some of these hierarchical positions under the wánax included the lawagetas (he who leads the people, a meaning which remains unclear), varying positions of which the meanings remain unknown (hektai, collectors of commodity and flock), scribes, mayors, vice-mayors, and varying styles of overseer. The term "basileus" is also familiar to the Mycenaean hierarchy as a local chieftain or leader, and would later come to replace wánax as the term for king after the collapse of Mycenaean civilization.[8]

This administrative body produced or obtained many artefacts by which they might increase their prestige,[11] or more practically manage the state of the wánax more effectively. Mycenaean administrative artefacts include tablets which carry inscriptions from a scribal body, among which are tablets of purely administrative work (accounting for state supplies of resources), which would have been designed to support the wánax and state administration, and to be supported by a state administration.[10] Much of the surviving Mycenaean administrative records which remain primarily deal with economic affairs, and the management of state resources. Mycenaean states were active participants in diplomacy and trade, between their fellow Mycenaean states and the broader interregional bodies which surrounded them.[12]

Warfare

[edit]Fortifications dominate the Mycenaean world, with such structures being erected across the Bronze Age, but particularly during the Late Bronze Age Collapse (where the necessity for such fortifications intensified), before the end of Mycenaean civilization. Being prolific builders of fortifications, wánaxes actively engaged in warlike campaigning in and around their states, though evidence for their direct participation is minimal. Evidence from Pylos suggests that the wánax was in possession of weapons specifically indicated as royal.[8] Stronger evidence exists that the wánax assigned military leadership to other members of the palatial elite. At Pylos, a name identified as e-ke-ra-wo is speculated to either be a wánax or another person of importance, and was tasked with managing the rowers of Pylos in particular.[6]

Ahhiyawa texts

[edit]The Ahhiyawa texts include correspondences between unnamed Mycenaean wánaxes and the Hittite kingdom. One such text from the collection, known as the Tawagalawa Letter, was composed from the King of Hatti to an unnamed Mycenaean wánax, and contained diplomatic correspondences regarding a man by the name of Piyamaradu, who had acted against the Hittite King; and that the wánax should either return him or reject him.[12] The same text informs that the unnamed wánax had previously been in conflict with the Hittites over the territory of Wilusa, though there is no further conflict between them.[12] The Hittite King refers to the wánax not by title but as "brother" in these texts, a common practice in the ancient Near East in diplomatic correspondences with powers viewed as equal participants in interregional status. Another text which is heavily fragmented was sent by a wánax to the King of Hatti (likely Muwattalli II) concerning the ownership of islands.[12]

Economic participation

[edit]Wánaxes have much heavier evidence of participation in state economics, taking a more direct role rather than the hierarchical allocations and lack of evidence for administrative participation. The lands of the wánax were closely tied to economic output of foods and commodity goods.[8] Economically, various records exist which refer to wanakteros, royal craftsmen, under the employ of the wánax.[6][13] These craftsmen came in a variety of roles, from practical purposes to commodity production,[6][8] though not all craftsmen were exclusively royal in nature in the Mycenaean economic sphere.[14] Additionally, the royal designation is applied not only to craftsmen within the economy, but to storehouses of jars believed to contain olive oil; indicating the presence of royal products which were circulated within Mycenaean civilization and beyond.[6] Royal employment would indicate that the wánax acts much more closer to the economy as a sort of overseer or administrator than to many of the other tasks of the state. However, much of the records available concerning the role of wánax deal with economic information due to the importance of such scribal records to Mycenaean states, but does not discredit the participation of the wánax directly in other facets of the state. Mycenaean elite also utilized luxury items to accentuate their status, and placed high value economically and politically on such items.[11][14]

Another major economic function of the wánax was the participation in and organization of elaborate feasting amongst the Mycenaean elite, and shared with those outside the immediate palatial elite as well. Feasts required extensive planning and organization on the part of the wánax and palatial administration, which needed to mobilize large amounts of resources in order to host such elaborate feasts.[11] A major feature of these feasts involved drinking, as evidenced by the many prestige drinking vessels recovered.[11] These processes economically involved the collection and feeding of vast quantities of livestock, luxury items for the elite (feasting equipment like luxury pottery and cups) and politically demonstrated the authority of the wánax with his elite.[11] One manner in which feasting further secured the wánax economically and politically was the inclusion of lower elites (local leaders and other non-palatial authorities under the wánax) in feasting, both building social connections to the wánax and economically persuading lower elites to dedicate resources to palatial feasting.

Religious participation

[edit]The wánax were extensively involved in cultic practice during the Mycenean period of Greek religion, participating and playing a central role in Mycenaean religion.[8] Much of this was involved in ritual practice from feasting to ceremonies dedicated to the gods, with the wánax being evidenced to perhaps been ritually involved in cultic activities which involve the use of oil and spice. Mention of oil and spice, and mention of the wánax being closely related to religious practice, has led some scholars to speculate the potential of kingship being semi-divine in Mycenaean Greece; however evidence is lacking for this claim, perhaps from an overzealous desire to seek out connections between wánax and goddesses such as Demeter and Persephone. It is more likely the wánax was viewed as a mortal king. Wánaxes were especially involved in feasting, and therefore all religious feasting would've been reliant on the wánax to economically support and participate in.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b ἄναξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Beekes, Robert (2010) [2009]. "S.v. ἄναξ". Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Vol. 1. With the assistance of Lucien van Beek. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9789004174184.

- ^ "The Linear B word wa-na-sa". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- ^ "The Linear B word wa-na-ka-te-ro". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- ^ ἀνάκτορον in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Duhoux, Yves (2008). A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek texts and their World Volume 1. Peeters.

- ^ a b Grottanelli, Cristiano (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion: Kingship in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Gale. pp. 5165–5166.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Deger-Jalkotzy, Sigrid (2006). Ancient Greece: From the Mycenaean Palaces to the Age of Homer. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748627295.

- ^ Willms, Lothar (2010). "On the IE Etymology of Greek (w)anax". Glotta. 86 (1–4): 232–271. doi:10.13109/glot.2010.86.14.232. ISSN 0017-1298. JSTOR 41219890.

- ^ a b Colvin, Stephen (2014). A Brief History of Ancient Greek. John Wiley & Sons. p. 40. ISBN 9781118610725.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, James (2004). "A Survey of Evidence for Feasting in Mycenaean Society". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 73 (2): 133–178. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.133. JSTOR 4134891. S2CID 54957703.

- ^ a b c d Beckman, Gary (2011). The Ahhiyawa texts. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 101–267. ISBN 9781589832688.

- ^ Papadopoulos, John (2018). "Greek Protohistories". World Archaeology. 50 (5): 690–705. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1568294. S2CID 219614767.

- ^ a b Aprile, Jamie (2013). "Crafts, Specialists, and Markets in Mycenaean Greece. The New Political Economy of Nichoria: Using Intrasite Distribution Data to Investigate Regional Institutions". American Journal of Archaeology. 117 (3): 429–436. doi:10.3764/aja.117.3.0429. hdl:2152/31046. JSTOR 10.3764/aja.117.3.0429. S2CID 148377869.

Further reading

[edit]- Haskell, Halford W. (2004). "Wanax to Wanax: Regional Trade Patterns in Mycenaean Crete". Hesperia. 33 (Supplements): 151–160. JSTOR 1354067.

- Hooker, James T. (1979). "The Wanax in Linear B Texts". Kadmos. 18 (2): 100–111. doi:10.1515/kadm.1979.18.2.100. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 162262172.

- Kilian, Klaus (1988). "The Emergence of Wanax Ideology in the Mycenaean Palaces". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 7 (3): 291–302. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1988.tb00182.x.

- Palaima, Thomas G. (1995). "The Nature of the Mycenaean Wanax: Non-Indo-European Origins and Priestly Functions". In Rehak, Paul (ed.). The Role of the Ruler in the Prehistoric Aegean. Aegaeum. Vol. 11. Liège: Univ., Histoire de l'Art et Archéologie de la Grèce Antique. pp. 119–139. ISBN 90-429-2411-X.

- Schon, Robert (2011). "Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. By Appointment to His Majesty the Wanax: Value-Added Goods and Redistribution in Mycenaean Palatial Economies". American Journal of Archaeology. 115 (2): 219–227. doi:10.3764/aja.115.2.0219. S2CID 245264762.

- Willms, Lothar (2010). "On the IE Etymology of Greek (w)anax". Glotta. 86 (1–4): 232–271. doi:10.13109/glot.2010.86.14.232. JSTOR 41219890.

- Yamagata, Naoko (1997). "ἄναξ and βασιλεύς in Homer". Classical Quarterly. 47 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/cq/47.1.1. ISSN 0009-8388.