Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Indra

View on Wikipedia

| Indra | |

|---|---|

King of the Devas and Svarga National god of the Vedic Aryans God of Heaven, Weather, Thunder, and War The Supreme God (Vedism) | |

A gilt-copper sculpture of Indra, c. 16th-century | |

| Other names | Devendra, Mahendra, Surendra, Surapati, Suresha, Devesha, Devaraja, Amaresha, Vendhan, |

| Devanagari | इन्द्र |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Indra |

| Affiliation | Adityas, Deva, Dikpala, Parjanya |

| Abode | Amarāvati, the capital of Indraloka in Svarga[1] |

| Mantra | Oṁ Indradevāya Namaḥ Oṁ Indrarājāya Vidmahe Mahā Indrāya Dhīmahi Tanno Indraḥ Pracodayāt |

| Weapon | Vajra (thunderbolt), Astras, Indrastra, Aindrastra, |

| Symbols | Vajra, Indra's net |

| Day | Sunday |

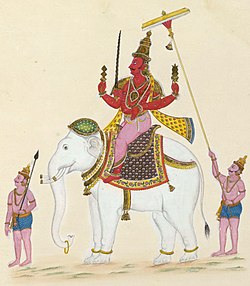

| Mount | Airavata (white elephant), Uchchaihshravas (white horse), A divine chariot yoked with eight horses |

| Texts | Vedas, Puranas, Upanishads |

| Gender | Male |

| Festivals | Indra Jatra, Indra Vila, Raksha Bandhan, Lohri, Sawan, Deepavali |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Vedic: Dyaus and Prithvi; or Tvashtri and his wife Itihasa-Puranic: Kashyapa and Aditi[2][3][a] |

| Siblings | Adityas including Surya, Varuna, Bhaga, Aryaman, Mitra, Savitr and Vamana |

| Consort | Shachi |

| Children | |

| Equivalents | |

| Buddhist | Śakra |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Indra (/ˈɪndrə/; Sanskrit: इन्द्र, IPA: [in̪d̪rɐ]) is the Hindu and Vedic god of heaven, weather, and war, considered the king of the devas[4] and svarga in Hinduism and Vedism. He is the national god of the Vedic Aryans, and is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war.[5][6][7][8]

Indra is the most frequently mentioned deity and the supreme God in the Rigveda.[9] during the early Vedic Period, He was considered superior to all other gods, and was celebrated for his powers based on his status as a god of order,[4] and as the one who killed the great evil, an asura named Vritra, who obstructed human prosperity and happiness. Indra destroys Vritra and his "deceiving forces", and thereby brings rain and sunshine as the saviour of mankind.[8][10]

Indra's significance diminishes in the post-Vedic Indian literature, but he still plays an important role in various mythological events. He is depicted as a powerful hero.[11]

According to the Vishnu Purana, Indra is the title borne by the king of the gods, which changes every Manvantara – a cyclic period of time in Hindu cosmology. Each Manvantara has its own Indra and the Indra of the current Manvantara is called Purandhara.[12][13][14][15]

Indra is also depicted in Buddhist (Pali: Indā)[16][17] and Jain[18] mythologies. Indra rules over the much-sought Devas realm of rebirth within the Samsara doctrine of Buddhist traditions.[19] However, like the post-Vedic Hindu texts, Indra is also a subject of ridicule and reduced to a figurehead status in Buddhist texts,[20] shown as a god who suffers rebirth.[19] In Jain traditions, unlike Buddhism and Hinduism, Indra is not the king of gods, but the king of superhumans residing in Svarga-Loka, and very much a part of Jain rebirth cosmology.[21] He is also the one who appears with his consort Indrani to celebrate the auspicious moments in the life of a Jain Tirthankara, an iconography that suggests the king and queen of superhumans residing in Svarga reverentially marking the spiritual journey of a Jain.[22][23] He is a rough equivalent to Zeus in Greek mythology, or Jupiter in Roman mythology. Indra's powers are similar to other Indo-European deities such as Norse Odin, Perun, Perkūnas, Zalmoxis, Taranis, and Thor, part of the greater Proto-Indo-European mythology.[8][24][25]

Indra's iconography shows him wielding his vajra and riding his vahana, Airavata.[26][27] Indra's abode is in the capital city of Svarga, Amaravati, though he is also associated with Mount Meru (also called Sumeru).[19][28]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]

The etymological roots of Indra are unclear, and it has been a contested topic among scholars since the 19th-century, one with many proposals.[30][31] The significant proposals have been:

- root ind-u, or "spirit", based on the Vedic mythology that he conquered rain and brought it down to earth.[26][30]

- root ind, or "equipped with great power". This was proposed by Vopadeva.[26]

- root idh or "spirit", and ina or "strong".[32][33]

- root indha, or "igniter", for his ability to bring light and power (indriya) that ignites the vital forces of life (prana). This is based on Shatapatha Brahmana.[34]

- root idam-dra, or "It seeing" which is a reference to the one who first perceived the self-sufficient metaphysical Brahman. This is based on Aitareya Upanishad.[26]

- roots in ancient Indo-European, Indo-Aryan deities.[35] For example, states John Colarusso, as a reflex of proto-Indo-European *h₂nḗr-, Greek anēr, Sabine nerō, Avestan nar-, Umbrian nerus, Old Irish nert, Pashto nər, Ossetic nart, and others which all refer to "most manly" or "hero".[35]

- roots in ancient Proto-Uralic paganism, possibly coming from the old Uralic sky-god Ilmarinen.[36]

Colonial era scholarship proposed that Indra shares etymological roots with Avestan Andra, Old High German *antra ("giant"), or Old Church Slavonic jedru ("strong"), but Max Muller critiqued these proposals as untenable.[30][37] Later scholarship has linked Vedic Indra to Aynar (the Great One) of Circassian, Abaza and Ubykh mythology, and Innara of Hittite mythology.[35][38] Colarusso suggests a Pontic[b] origin and that both the phonology and the context of Indra in Indian religions is best explained from Indo-Aryan roots and a Circassian etymology (i.e. *inra).[35] Modern scholarship suggests the name originated at the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex where the Aryans lived before settling in India.

Other languages

[edit]In other languages, he is also known as

- Ashkun: Indra

- Bengali: ইন্দ্র (Indro)

- Burmese: သိကြားမင်း ([ðədʑá mɪ́ɰ̃])

- Chinese: 因陀羅 (Yīntuóluó) or 帝釋天 (Dìshìtiān)

- Indonesian/Malay: (Indera)

- Japanese: 帝釈天 (Taishakuten).[39]

- Javanese: ꦧꦛꦫꦲꦶꦤ꧀ꦢꦿ (Bathara Indra)

- Kamkata-vari: Inra

- Kannada: ಇಂದ್ರ (Indra)

- Khmer: ព្រះឥន្ទ្រ (Preah In pronounced [preah ʔən])

- Korean: 제석천 (Jeseokcheon)

- Lanna: ᩍᨶ᩠ᨴᩣ (Intha) or ᨻᩕ᩠ᨿᩣᩍᨶ᩠ᨴ᩼ (Pha Nya In)

- Lao: ພະອິນ (Pha In) or ພະຍາອິນ (Pha Nya In)

- Malayalam: ഇന്ദ്രൻ (Indran)

- Mon: ဣန် (In)

- Mongolian: Индра (Indra)

- Odia: ଇନ୍ଦ୍ର (Indrô)

- Prasun: Indr

- Sinhala: ඉඳු (In̆du) or ඉන්ද්ර (Indra)

- Tai Lue: ᦀᦲᧃ (In) or ᦘᦍᦱᦀᦲᧃ (Pha Ya In)

- Tamil: இந்திரன் (Inthiran)

- Telugu: ఇంద్రుఁడు (Indrun̆ḍu or Indrũḍu)

- Tibetan: དབང་པོ་ (dbang po)

- Thai: พระอินทร์ (Phra In)

- Waigali: Indr

Epithets

[edit]Indra has many epithets in the Indian religions, notably Śakra (शक्र, powerful one),

- Vṛṣan (वृषन्, mighty)

- Vṛtrahan (वृत्रहन्, slayer of Vṛtra)

- Meghavāhana (मेघवाहन, he whose vehicle is cloud)

- Devarāja (देवराज, king of deities)

- Devendra (देवेन्द्र, the lord of deities)[40]

- Surendra (सुरेन्द्र, chief of deities)

- Svargapati (स्वर्गपति, the lord of heaven)

- Śatakratu (शतक्रतु one who performs 100 sacrifices).

- Vajrapāṇī (वज्रपाणि, wielder of Vajra, i.e., thunderbolt)

- Vāsava (वासव, lord of Vasus)

- Purandara (पुरंदर, the breaker of forts)

- Kaushika (कौशिक, Vishvamitra was born as the embodiment of Indra)

- Shachin or Shachindra (शचीन, the consort of Shachi).

- Parjanya (पर्जन्य, Rain)

Origins

[edit]

Indra is of ancient but unclear origin. Aspects of Indra as a deity are cognate to other Indo-European gods; there are thunder gods such as Thor, Perun, and Zeus who share parts of his heroic mythologies, act as king of gods, and all are linked to "rain and thunder".[41] The similarities between Indra of Vedic mythology and of Thor of Nordic and Germanic mythologies are significant, states Max Müller. Both Indra and Thor are storm gods, with powers over lightning and thunder, both carry a hammer or an equivalent, for both the weapon returns to their hand after they hurl it, both are associated with bulls in the earliest layer of respective texts, both use thunder as a battle-cry, both are protectors of mankind, both are described with legends about "milking the cloud-cows", both are benevolent giants, gods of strength, of life, of marriage and the healing gods.[42]

Michael Janda suggests that Indra has origins in the Indo-European *trigw-welumos [or rather *trigw-t-welumos] "smasher of the enclosure" (of Vritra, Vala) and diye-snūtyos "impeller of streams" (the liberated rivers, corresponding to Vedic apam ajas "agitator of the waters").[43] Brave and heroic Innara or Inra, which sounds like Indra, is mentioned among the gods of the Mitanni, a Hurrian-speaking people of Hittite region.[44]

Indra as a deity was known in the capital of the Hittite Empire in northeastern Asia minor, as evidenced by the inscriptions on the Boghaz-köi clay tablets dated to about 1400 BCE. This tablet mentions a treaty, but its significance is in four names it includes reverentially as Mi-it-ra, U-ru-w-na, In-da-ra and Na-sa-at-ti-ia. These are respectively, Mitra, Varuna, Indra and Nasatya-Asvin of the Vedic pantheon as revered deities, and these are also found in Avestan pantheon but with Indra and Naonhaitya as demons. This at least suggests that Indra and his fellow deities were in vogue in South Asia and Asia minor by about mid 2nd-millennium BCE.[32][45]

Indra is praised as the highest god in 250 hymns of the Rigveda – a Hindu scripture dated to have been composed sometime between 1700 and 1100 BCE. He is co-praised as the supreme in another 50 hymns, thus making him one of the most celebrated Vedic deities.[32] He is also mentioned in ancient Indo-Iranian literature, but with a major inconsistency when contrasted with the Vedas. In the Vedic literature, Indra is a heroic god. In the Avestan (ancient, pre-Islamic Iranian) texts such as Vd. 10.9, Dk. 9.3 and Gbd 27.6-34.27, Indra – or accurately Andra[46] – is a gigantic demon who opposes truth.[35][c] In the Vedic texts, Indra kills the archenemy and demon Vritra who threatens mankind. In the Avestan texts, Vritra is not found.[46]

According to David Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably emerged among Indo-European immigrants in the contact zone between the Zeravshan River (present-day Uzbekistan) and (present-day) Iran.[47] It was "a syncretic mixture of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements",[47] which borrowed "distinctive religious beliefs and practices"[48] from the Bactria–Margiana Culture.[48] At least 383 non-Indo-European words were found in this culture, including the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.[49] According to Anthony,

Many of the qualities of Indo-Iranian god of might/victory, Verethraghna, were transferred to the god Indra, who became the central deity of the developing Old Indic culture. Indra was the subject of 250 hymns, a quarter of the Rig Veda. He was associated more than any other deity with Soma, a stimulant drug (perhaps derived from Ephedra) probably borrowed from the BMAC religion. His rise to prominence was a peculiar trait of the Old Indic speakers.[50]

However, according to Paul Thieme, "there is no valid justification for supposing that the Proto-Aryan adjective *vrtraghan was specifically connected with *Indra or any other particular god."[51]

Iconography

[edit]In Rigveda, Indra is described as strong willed, armed with a thunderbolt, riding a chariot:

5. Let bullish heaven strengthen you, the bull; as bull you travel with your two bullish fallow bays. As bull with a bullish chariot, well-lipped one, as bull with bullish will, you of the mace, set us up in loot.

— Rigveda, Book 5, Hymn 37: Jamison[52]

Indra's weapon, which he used to kill the evil Vritra, is the vajra or thunderbolt. Other alternate iconographic symbolism for him includes a bow (sometimes as a colorful rainbow), a sword, a net, a noose, a hook, or a conch.[53] The thunderbolt of Indra is called Bhaudhara.[54]

In the post-Vedic period, he rides a large, four-tusked white elephant called Airavata.[26] In sculpture and relief artworks in temples, he typically sits on an elephant or is near one. When he is shown to have two, he holds the vajra and a bow.[55]

In the Shatapatha Brahmana and in Shaktism traditions, Indra is stated to be the same as the goddess Shodashi (Tripura Sundari), and her iconography is described similarly to that of Indra.[56]

The rainbow is called Indra's Bow (Sanskrit: इन्द्रधनुस् indradhanus).[53]

Literature

[edit]Vedic texts

[edit]

Indra was a prominent deity in the Historical Vedic religion.[32] In Vedic times Indra was described in Rig Veda 6.30.4 as superior to any other god. Sayana in his commentary on Rig Veda 6.47.18 described Indra as assuming many forms, making Agni, Vishnu, and Rudra his illusory forms.[57]

Over a quarter of the 1,028 hymns of the Rigveda mention Indra, making him the most referred to deity.[32][58] These hymns present a complex picture of Indra, but some aspects of Indra are often repeated. Of these, the most common theme is where he as the god with thunderbolt kills the evil serpent Vritra that held back rains, and thus released rains and land nourishing rivers.[30] For example, the Rigvedic hymn 1.32 dedicated to Indra reads:

इन्द्रस्य नु वीर्याणि प्र वोचं यानि चकार प्रथमानि वज्री ।

अहन्नहिमन्वपस्ततर्द प्र वक्षणा अभिनत्पर्वतानाम् ॥१।।

अहन्नहिं पर्वते शिश्रियाणं त्वष्टास्मै वज्रं स्वर्यं ततक्ष ।

वाश्रा इव धेनवः स्यन्दमाना अञ्जः समुद्रमव जग्मुरापः ॥२।।

1. Now I shall proclaim the heroic deeds of Indra, those foremost deeds that the mace-wielder performed:

He smashed the serpent. He bored out the waters. He split the bellies of the mountains.

2. He smashed the serpent resting on the mountain—for him Tvaṣṭar had fashioned the resounding [sunlike] mace.

Like bellowing milk-cows, streaming out, the waters went straight down to the sea.[60]

In the myth, Vṛtra has coiled around a mountain and has trapped all the waters, namely the Seven Rivers. All the gods abandon Indra out of fear of Vṛtra. Indra uses his vajra, a mace, to kill Vritra and smash open the mountains to release the waters. In some versions, he is aided by the Maruts or other deities, and sometimes cattle and the sun is also released from the mountain.[61][62] In one interpretation by Oldenberg, the hymns are referring to the snaking thunderstorm clouds that gather with bellowing winds (Vritra), Indra is then seen as the storm god who intervenes in these clouds with his thunderbolts, which then release the rains nourishing the parched land, crops and thus humanity.[63] In another interpretation by Hillebrandt, Indra is a symbolic sun god (Surya) and Vritra is a symbolic winter-giant (historic mini cycles of ice age, cold) in the earliest, not the later, hymns of Rigveda. The Vritra is an ice-demon of colder central Asia and northern latitudes, who holds back the water. Indra is the one who releases the water from the winter demon, an idea that later metamorphosed into his role as storm god.[63] According to Griswold, this is not a completely convincing interpretation, because Indra is simultaneously a lightning god, a rain god and a river-helping god in the Vedas. Further, the Vritra demon that Indra slew is best understood as any obstruction, whether it be clouds that refuse to release rain or mountains or snow that hold back the water.[63] Jamison and Brereton also state that Vritra is best understood as any obstacle. The Vritra myth is associated with the Midday Pressing of soma, which is dedicated to Indra or Indra and the Maruts.[61]

Even though Indra is declared as the king of gods in some verses, there is no consistent subordination of other gods to Indra. In Vedic thought, all gods and goddesses are equivalent and aspects of the same eternal abstract Brahman, none consistently superior, none consistently inferior. All gods obey Indra, but all gods also obey Varuna, Vishnu, Rudra and others when the situation arises. Further, Indra also accepts and follows the instructions of Savitr (solar deity).[64] Indra, like all Vedic deities, is a part of henotheistic theology of ancient India.[65]

The second-most important myth about Indra is about the Vala cave. In this story, the Panis have stolen cattle and hidden them in the Vala cave. Here Indra utilizes the power of the songs he chants to split the cave open to release the cattle and dawn. He is accompanied in the cave by the Angirases (and sometimes Navagvas or the Daśagvas). Here Indra exemplifies his role as a priest-king, called bṛhaspati. Eventually later in the Rigveda, Bṛhaspati and Indra become separate deities as both Indra and the Vedic king lose their priestly functions. The Vala myth was associated with the Morning Pressing of soma, in which cattle was donated to priests, called dakṣiṇā.[61]

Indra is not a visible object of nature in the Vedic texts, nor is he a personification of any object, but that agent which causes the lightning, the rains and the rivers to flow.[66] His myths and adventures in the Vedic literature are numerous, ranging from harnessing the rains, cutting through mountains to help rivers flow, helping land becoming fertile, unleashing sun by defeating the clouds, warming the land by overcoming the winter forces, winning the light and dawn for mankind, putting milk in the cows, rejuvenating the immobile into something mobile and prosperous, and in general, he is depicted as removing any and all sorts of obstacles to human progress.[67] The Vedic prayers to Indra, states Jan Gonda, generally ask "produce success of this rite, throw down those who hate the materialized Brahman".[68] The hymns of Rigveda declare him to be the "king that moves and moves not", the friend of mankind who holds the different tribes on earth together.[69]

Indra is often presented as the twin brother of Agni (fire) – another major Vedic deity.[70] Yet, he is also presented to be the same, states Max Muller, as in Rigvedic hymn 2.1.3, which states, "Thou Agni, art Indra, a bull among all beings; thou art the wide-ruling Vishnu, worthy of adoration. Thou art the Brahman, (...)."[71] He is also part of one of many Vedic trinities as "Agni, Indra and Surya", representing the "creator-maintainer-destroyer" aspects of existence in Hindu thought.[58][d]

Rigveda 2.1.3 Jamison 2014[74]

- You, Agni, as bull of beings, are Indra; you, wide-going, worthy of homage, are Viṣṇu. You, o lord of the sacred formulation, finder of wealth, are the Brahman [Formulator]; you, o Apportioner, are accompanied by Plenitude.

Parentage of Indra is inconsistent in Vedic texts, and in fact Rigveda 4.17.12 states that Indra himself may not even know that much about his mother and father. Some verses of Vedas suggest that his mother was a grishti (a cow), while other verses name her Nishtigri. The medieval commentator Sayana identified her with Aditi, the goddess who is his mother in later Hinduism. The Atharvaveda states Indra's mother is Ekashtaka, daughter of Prajapati. Some verses of Vedic texts state that Indra's father is Tvaṣṭar or sometimes the couple Dyaus and Prithvi are mentioned as his parents.[74](pp39, 582)[75][76] According to a legend found in it[where?], before Indra is born, his mother attempts to persuade him to not take an unnatural exit from her womb. Immediately after birth, Indra steals soma from his father, and Indra's mother offers the drink to him. After Indra's birth, Indra's mother reassures Indra that he will prevail in his rivalry with his father, Tvaṣṭar. Both the unnatural exit from the womb and rivalry with the father are universal attributes of heroes.[61] In the Rigveda, Indra's wife is Indrani, alias Shachi, and she is described to be extremely proud about her status.[77] Rigveda 4.18.8 says after his birth Indra got swallowed by a demon Kushava.[78]

Indra is also found in many other myths that are poorly understood. In one, Indra crushes the cart of Ushas (Dawn), and she runs away. In another Indra beats Surya in a chariot race by tearing off the wheel of his chariot. This is connected to a myth where Indra and his sidekick Kutsa ride the same chariot drawn by the horses of the wind to the house of Uśanā Kāvya to receive aid before killing Śuṣṇa, the enemy of Kutsa. In one myth Indra (in some versions[which?] helped by Viṣṇu) shoots a boar named Emuṣa in order to obtain special rice porridge hidden inside or behind a mountain. Another myth has Indra kill Namuci by beheading him. In later versions of that myth Indra does this through trickery involving the foam of water. Other beings slain by Indra include Śambara, Pipru, Varcin, Dhuni and Cumuri, and others. Indra's chariot is pulled by fallow bay horses described as hárī. They bring Indra to and from the sacrifice, and are even offered their own roasted grains.[61]

Upanishads

[edit]The ancient Aitareya Upanishad equates Indra, along with other deities, with Atman (soul, self) in the Vedanta's spirit of internalization of rituals and gods. It begins with its cosmological theory in verse 1.1.1 by stating that, "in the beginning, Atman, verily one only, was here - no other blinking thing whatever; he bethought himself: let me now create worlds".[79](p294)[80] This soul, which the text refers to as Brahman as well, then proceeds to create the worlds and beings in those worlds wherein all Vedic gods and goddesses such as sun-god, moon-god, Agni, and other divinities become active cooperative organs of the body.[80][79](p295–297)[81] The Atman thereafter creates food, and thus emerges a sustainable non-sentient universe, according to the Upanishad. The eternal Atman then enters each living being making the universe full of sentient beings, but these living beings fail to perceive their Atman. The first one to see the Atman as Brahman, asserts the Upanishad, said, "idam adarsha or "I have seen It".[80] Others then called this first seer as Idam-dra or "It-seeing", which over time came to be cryptically known as "Indra", because, claims Aitareya Upanishad, everyone including the gods like short nicknames.[79](pp297–298) The passing mention of Indra in this Upanishad, states Alain Daniélou, is a symbolic folk etymology.[26]

The section 3.9 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad connects Indra to thunder, thunderbolt and release of waters.[82] In section 5.1 of the Avyakta Upanishad, Indra is praised as he who embodies the qualities of all gods.[58]

Post-Vedic texts

[edit]In post-Vedic texts, Indra is depicted as an intoxicated hedonistic god. His importance declines, and he evolves into a minor deity in comparison to others in the Hindu pantheon, such as Vishnu, Shiva, or Devi. In Hindu texts, Indra is some times known as an aspect (avatar) of Shiva.[58]

In the Puranas, Ramayana and Mahabharata, the divine sage Kashyapa is described as the father of Indra, and Aditi as his mother. In this tradition, he is presented as one of their thirty-three sons.[83][75] Indra married Shachi, the daughter of the danava Puloman. Most texts state that Indra had only one wife, though sometimes other names are mentioned.[75] The text Bhagavata Purana mention that Indra and Shachi had three sons named Jayanta, Rishabha, Midhusha.[84] Some listings add Nilambara and Rbhus.[76] Indra and Shachi also had two daughters, Jayanti and Devasena. Jayanti becomes the spouse of Shukra, while Devasena marries the war god Kartikeya.[12] Indra is depicted as the spiritual father of Vali in the Ramayana and Arjuna in the Mahabharata.[20] Since he is known for mastering all weapons in warfare, his spiritual sons Vali and Arjuna also share his martial attributes. He has a charioteer named Matali.[85]

Indra had multiple affairs with other women. One such was Ahalya, the wife of sage Gautama. Indra was cursed by the sage. Although the Brahmanas (9th to 6th centuries BCE) are the earliest scriptures to hint at their relationship, the 7th- to 4th-centuries BCE Hindu epic Ramayana – whose hero is Rama – is the first to explicitly mention the affair in detail.[86]

Indra becomes a source of nuisance rains in the Puranas, caused out of anger with an intent to hurt mankind. Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, comes to the rescue by lifting Mount Govardhana on his fingertip, and letting mankind shelter under the mountain till Indra exhausts his anger and relents.[20] According to the Mahabharata, Indra disguises himself as a Brahmin and approaches Karna and asks for his kavacha (body armor) and kundala (earrings) as charity. Although being aware of his true identity, Karna peeled off his kavacha and kundala and fulfilled the wish of Indra. Pleased by this act, Indra gifts Karna a celestial dart called the Vasavi Shakti.[citation needed]

According to the Vishnu Purana, Indra is the position of being the king of the gods which changes in every Manvantara—a cyclic period of time in Hindu cosmology. Each Manvantara has its own Indra and the Indra of the current Manvantara is called Purandhara.[12][13][14][15]

Sangam literature (300 BCE–300 CE)

[edit]The Sangam literature of the Tamil language contains more stories about Indra by various authors. In the Cilappatikaram, Indra is described as Malai venkudai mannavan, literally meaning, "Indra with the pearl-garland and white umbrella".[87]

Sangam literature also describes Indra Vila (festival for Indra), the festival for want of rain, celebrated for one full month starting from the full moon in Uttrai (Chaitra) and completed on the full moon in Puyali (Vaisakha). This is described in the epic Cilappatikaram in detail.[88]

In his work Tirukkural (before c. 5th century CE), Valluvar cites Indra to exemplify the virtue of conquest over one's senses.[89][90]

In other religions

[edit]Indra is an important deity worshipped by the Kalash people, indicating his prominence in ancient Hinduism.[91][92][e][93][f][94][95][g][96][h][97]

Buddhism

[edit]

The Buddhist cosmology places Indra above Mount Sumeru, in Trayastrimsha heaven.[17] He resides and rules over one of the six realms of rebirth, the Deva realm of Saṃsāra, that is widely sought in the Buddhist tradition.[98][j] Rebirth in the realm of Indra is a consequence of very good Karma (Pali: kamma) and accumulated merit during a human life.[101]

In Buddhism, Indra is commonly called by his other name, Śakra or Sakka, ruler of the Trāyastriṃśa heaven.[103] Śakra is sometimes referred to as Devānām Indra or "Lord of the Devas". Buddhist texts also refer to Indra by numerous names and epithets, as is the case with Hindu and Jain texts. For example, Asvaghosha's Buddhacarita in different sections refers to Indra with terms such as "the thousand eyed",[104] Puramdara,[105] Lekharshabha,[106] Mahendra, Marutvat, Valabhid and Maghavat.[107] Elsewhere, he is known as Devarajan (literally, "the king of gods"). These names reflect a large overlap between Hinduism and Buddhism, and the adoption of many Vedic terminology and concepts into Buddhist thought.[108] Even the term Śakra, which means "mighty", appears in the Vedic texts such as in hymn 5.34 of the Rigveda.[26][109]

In Theravada Buddhism Indra is referred to as Indā in evening chanting such as the Udissanādiṭṭhānagāthā (Iminā).[110]

The Bimaran Casket made of gold inset with garnet, dated to be around 60 CE, but some proposals dating it to the 1st century BCE, is among the earliest archaeological evidences available that establish the importance of Indra in Buddhist mythology. The artwork shows the Buddha flanked by gods Brahma and Indra.[111][112]

In China, Korea, and Japan, he is known by the characters 帝釋天 (Chinese: 釋提桓因, pinyin: shì dī huán yīn, Korean: "Je-seok-cheon" or 桓因 Hwan-in, Japanese: "Tai-shaku-ten", kanji: 帝釈天) and usually appears opposite Brahma in Buddhist art. Brahma and Indra are revered together as protectors of the historical Buddha (Chinese: 釋迦, kanji: 釈迦, also known as Shakyamuni), and are frequently shown giving the infant Buddha his first bath. Although Indra is often depicted like a bodhisattva in the Far East, typically in Tang dynasty costume, his iconography also includes a martial aspect, wielding a thunderbolt from atop his elephant mount.[citation needed]

In some schools of Buddhism and in Hinduism, the image of Indra's net is a metaphor for the emptiness of all things, and at the same time a metaphor for the understanding of the universe as a web of connections and interdependences.[113][circular reference]

In China, Indra (帝釋天 Dìshìtiān) is regarded as one of the twenty-four protective devas (二十四諸天 Èrshísì zhūtiān) of Buddhism. In Chinese Buddhist temples, his statue is usually enshrined in the Mahavira Hall along with the other devas.

In Japan, Indra (帝釈天 Taishakuten) is one of the twelve Devas, as guardian deities, who are found in or around Buddhist temples (十二天Jūni-ten).[114][115][116][117]

The ceremonial name of Bangkok claims that the city was "given by Indra and built by Vishvakarman."[118]

Jainism

[edit]Indra in Jain mythology always serves the Tirthankara teachers. Indra most commonly appears in stories related to Tirthankaras, in which Indra himself manages and celebrates the five auspicious events in that Tirthankara's life, such as Chavan kalyanak, Janma kalyanak, Diksha kalyanak, Kevala Jnana kalyanak, and moksha kalyanak.[119]

There are sixty-four Indras in Jain literature, each ruling over different heavenly realms where heavenly souls who have not yet gained Kaivalya (moksha) are reborn according to Jainism.[22][120] Among these many Indras, the ruler of the first Kalpa heaven is the Indra who is known as Saudharma in Digambara, and Sakra in Śvētāmbara tradition. He is most preferred, discussed and often depicted in Jain caves and marble temples, often with his wife Indrani.[120](pp25–28)[121] They greet the devotee as he or she walks in, flank the entrance to an idol of Jina (conqueror), and lead the gods as they are shown celebrating the five auspicious moments in a Jina's life, including his birth.[22] These Indra-related stories are enacted by laypeople in Jainism tradition during special Puja (worship) or festive remembrances.[22][120](pp29–33)

In the South Indian Digambara Jain community, Indra is also the title of hereditary priests who preside over Jain temple functions.[22]

Zoroastrianism

[edit]As the Iranian and Indian religions diverged from each other, the two main groupings of deities, the asuras (Iranian ahura) and daevas (Indian deva) acquired opposite features.[speculation?] For reasons that are not entirely clear[citation needed], the asuras/ahuras became demonized in India and elevated in Iran while the devas/daevas became demonized among the Iranians and elevated in India. In the Vendidad, one part of the Avesta, Indra is mentioned along with Nanghaithya (Vedic Nasatya) and Saurva (Śarva) as a relatively minor demon.[122][123] At the same time, many of the features of Indra in the Rigveda are shared with the ahuras Mithra and Verethragna and the Iranian legendary hero Thraetona (Fereydun). It is possible that Indra, originally a minor deity who later acquired greater significance, acquired the traits of other deities as his importance increased among the Indo-Aryans.[123]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For various other versions, see #Literature

- ^ The Pontic is the region near the Black Sea.

- ^ In deities that are similar to Indra in the Hittite and European mythologies, he is also heroic.[35]

- ^ The Trimurti idea of Hinduism, states Jan Gonda, "seems to have developed from ancient cosmological and ritualistic speculations about the triple character of an individual god, in the first place of Agni, whose births are three or threefold, and who is threefold light, has three bodies and three stations".[72](pp218–219) Other trinities, beyond the more common "Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva", mentioned in ancient and medieval Hindu texts include: "Indra, Vishnu, Brahmanaspati", "Agni, Indra, Surya", "Agni, Vayu, Aditya", "Mahalakshmi, Mahasarasvati, and Mahakali", and others.[72](pp212–226)[73]

- ^ Prominent sites include Hadda, near Jalalabad, but Buddhism never seems to have penetrated the remote valleys of Nuristan, where the people continued to practise an early form of polytheistic Hinduism.[92]

- ^ Up until the late nineteenth century, many Nuristanis practised a primitive form of Hinduism. It was the last area in Afghanistan to convert to Islam — and the conversion was accomplished by the sword.[93]

- ^ Some of their deities who are worshiped in Kalash tribe are similar to the Hindu god and goddess like Mahadev in Hinduism is called Mahandeo in Kalash tribe. ... All the tribal also visit the Mahandeo for worship and pray. After that they reach to the gree (dancing place).[95]

- ^ The Kalasha are a unique people living in just three valleys near Chitral, Pakistan, the capital of North-West Frontier Province, which borders Afghanistan. Unlike their neighbors in the Hindu Kush Mountains on both the Afghan and Pakistani sides of the border the Kalasha have not converted to Islam. During the mid-20th century a few Kalasha villages in Pakistan were forcibly converted to this dominant religion, but the people fought the conversion and once official pressure was removed the vast majority continued to practice their own religion. Their religion is a form of Hinduism that recognizes many gods and spirits and has been related to the religion of the ancient Greeks ... given their Indo-Aryan language, ... the religion of the Kalasha is much more closely aligned to the Hinduism of their Indian neighbors that to the religion of Alexander the Great and his armies.[96]

- ^ For a vast majority of Buddhists in Theravadin countries, however, the order of monks is seen by lay Buddhists as a means of gaining the most merit in the hope of accumulating good karma for a better rebirth.[99]

- ^ Scholars[99][i][100] note that better rebirth, not nirvana, has been the primary focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists. This is sought in the Buddhist traditions through merit accumulation and good kamma.

References

[edit]- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2014). Hinduism: An alphabetical guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ Mani 1975.

- ^ a b Bauer, Susan Wise (2007). The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-393-05974-8.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). India Through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 66 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Shaw, Jeffrey M.; Demy, Timothy J. (27 March 2017). War and Religion: An encyclopedia of faith and conflict. Google Książki. ISBN 978-1-61069-517-6. [3 volumes]

- ^ Perry, Edward Delavan (1885). "Indra in the Rig-Veda". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 11 (1885): 121. doi:10.2307/592191. JSTOR 592191.

- ^ a b c Berry, Thomas (1996). Religions of India: Hinduism, Yoga, Buddhism. Columbia University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-231-10781-5.

- ^ Gonda, Jan (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. p. 3. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

- ^ Griswold, Hervey de Witt (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–180. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

- ^ "Ahalya, Ahalyā: 15 definitions". Wisdom Library. n.d. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. pp. 190, 251. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- ^ a b Dutt, Manmath Nath. Vishnu Purana. pp. 170–173.

- ^ a b Wilson, Horace Hayman (1840). "The Vishnu Purana". www.sacred-texts.com. Book III, Chapter I, pages 259–265. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ a b Gita Press Gorakhpur. Vishnu Puran Illustrated With Hindi Translations Gita Press Gorakhpur (in Sanskrit and Hindi). pp. 180–183.

- ^ "Dictionary | Buddhistdoor". www.buddhistdoor.net. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ a b Helen Josephine Baroni (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6.

- ^ Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-04-20629-8.

- ^ a b c Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 739–740. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger (2015), Indra: Indian deity, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Naomi Appleton (2014). Narrating Karma and Rebirth: Buddhist and Jain Multi-Life Stories. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50, 98. ISBN 978-1-139-91640-0.

- ^ a b c d e Kristi L. Wiley (2009). The A to Z of Jainism. Scarecrow Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2.

- ^ John E. Cort (22 March 2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

- ^ Madan, T.N. (2003). The Hinduism Omnibus. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-566411-9.

- ^ Bhattacharji, Sukumari (2015). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

- ^ Wilkings 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Sita Pieris; Ellen Raven (2010). ABIA: South and Southeast Asian Art and Archaeology Index: Volume Three – South Asia. BRILL Academic. p. 232. ISBN 978-90-04-19148-8.

- ^ a b c d Friedrich Max Müller (1903). Anthropological Religion: The Gifford Lectures Delivered Before the University of Glasgow in 1891. Longmans Green. pp. 395–398.

- ^ Chakravarty, Uma (1995). "On the etymology of the word ÍNDRA". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 76 (1–4): 27–33. JSTOR 41694367.

- ^ a b c d e Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–178 with footnote 1. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

- ^ Edward Delavan Perry (1885). "Indra in the Rig-Veda". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 11: 121. doi:10.2307/592191. JSTOR 592191.

- ^ Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 418 with footnote 148. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- ^ a b c d e f John Colarusso (2014). Nart Sagas from the Caucasus: Myths and Legends from the Circassians, Abazas, Abkhaz, and Ubykhs. Princeton University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4008-6528-4.

- ^ Merimaa, Juha (13 December 2019). "Suomen kieleen on tullut vaikutteita yllättävästä suunnasta – moni sana on jäänne kohtaamisista indoiranilaisten kanssa". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Winn, Shan M.M. (1995). Heaven, Heroes, and Happiness: The Indo-European roots of Western ideology. University Press of America. p. 371, note 1. ISBN 978-0-8191-9860-0.

- ^ Chakraborty, Uma (1997). Indra and Other Vedic Deities: A euhemeristic study. DK Printworld. pp. 91, 220. ISBN 978-81-246-0080-1.

- ^ Presidential Address W. H. D. Rouse Folklore, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Mar., 1907), pp. 12-23: "King of the Gods is Sakka, or Indra"

- ^ Wilkings 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Alexander Stuart Murray (1891). Manual of Mythology: Greek and Roman, Norse, and Old German, Hindoo and Egyptian Mythology, 2nd Edition. C. Scribner's sons. pp. 329–331.

- ^ Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. pp. 744–749.

- ^ Janda, Michael (2000). Eleusis: Das Indogermanische Erbe der Mysterien. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-3-85124-675-9.

- ^ von Dassow, Eva (2008). State and Society in the Late Bronze Age. University Press of Maryland. pp. 77, 85–86. ISBN 978-1-934309-14-8.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James (1955). The Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–321. GGKEY:FP2CEFT2WJH.

- ^ a b Müller, Friedrich Max (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. pp. 756–759.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007, p. 462.

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 454-455.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 454.

- ^ Thieme, Paul (October–December 1960). "The 'Aryan' gods of the Mitanni treaties". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 80 (4): 301–317. doi:10.2307/595878. JSTOR 595878.

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie; Brereton, Joel (23 February 2020). The Rigveda. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063339-4.

- ^ a b Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The classic work on Hindu polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). Gautam, K.S. (ed.). India through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 75.

- ^ Masson-Oursel & Morin 1976, p. 326.

- ^ Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ "Rig Veda 6.47.18 [English translation]". 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १.३२, Wikisource Rigveda Sanskrit text

- ^ Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-19-063339-4.

- ^ a b c d e Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0-19-063339-4.

- ^ Oldenberg, Hermann (2004) [1894 (First Edition), 1916 (Second Edition)]. Die Religion Des Veda [The Religion of the Veda] (in German). Translated by Shrotri, Shridhar B. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 77.

- ^ a b c Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 180–183 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

- ^ Arthur Berriedale Keith (1925). The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-81-208-0645-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 758.

- ^ Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 757.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. pp. 4–5. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. p. 12. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

- ^ Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 180, verse 1.32.15. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

- ^ Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 827.

- ^ Müller, Friedrich Max (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 828.

- ^ a b Gonda, Jan (1969). "The Hindu trinity". Anthropos. 63–64 (1–2): 212–226. JSTOR 40457085.

- ^ White, David (2006). Kiss of the Yogini. University of Chicago Press. pp. 4, 29. ISBN 978-0-226-89484-3.

- ^ a b Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: Earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 39, 582. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- ^ a b c Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ a b Jordan, Michael (14 May 2014). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0985-5.

- ^ Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious tradition. University of California Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ^ Griffith, R.T.H., ed. (1920). The Hymns of the Rigveda. Benares, IN: E.J. Lazarus and Co.

- ^ a b c Hume, Robert (1921). "verses 1.1.1, and 1.3.13-.3.14". The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. Oxford University Press. pp. 294–298 with footnotes.

- ^ a b c Deussen, Paul (1997). A Sixty Upanishads Of the Veda. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-81-208-0430-2.

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Greater Magadha: Studies in the culture of early India. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN 978-90-04-15719-4.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (1998). The Early Upanishads: Annotated text and translation. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9.

- ^ Mani, Vettam (1975). Purāṇic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Purāṇic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 318. ISBN 978-81-208-0597--2.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (December 1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ Dowson, John (5 November 2013). A Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology and Religion, Geography, History and Literature. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-136-39029-6.

- ^ Söhnen, Renate (February 1991). "Indra and Women". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 54 (1): 68–74. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00009617. ISSN 1474-0699. S2CID 162225024.

- ^ S Krishnamoorthy (2011). Silappadikaram. Bharathi Puthakalayam.

- ^ S Krishnamoorthy (2011). Silappadikaram. Bharathi Puthakalayam. pp. 31–36.

- ^ P. S. Sundaram (1987). Kural (Tiruvalluvar). Penguin Books. pp. 21, 159. ISBN 978-93-5118-015-9.

- ^ S. N. Kandasamy (2017). திருக்குறள்: ஆய்வுத் தெளிவுரை (அறத்துப்பால்) [Tirukkural: Research commentary: Book of Aram]. Chennai: Manivasagar Padhippagam. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Bezhan, Frud (19 April 2017). "Pakistan's Forgotten Pagans Get Their Due". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

About half of the Kalash practice a form of ancient Hinduism infused with old pagan and animist beliefs.

- ^ a b Barrington, Nicholas; Kendrick, Joseph T.; Schlagintweit, Reinhard (18 April 2006). A Passage to Nuristan: Exploring the mysterious Afghan hinterland. I.B. Tauris. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-84511-175-5.

- ^ a b Weiss, Mitch; Maurer, Kevin (31 December 2012). No Way Out: A story of valor in the mountains of Afghanistan. Berkley Caliber. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-425-25340-3.

- ^ Ghai, Rajat (17 February 2014). "Save the Kalash!". Business Standard India. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b Jamil, Kashif (19 August 2019). "Uchal — a festival of shepherds and farmers of the Kalash tribe". Daily Times. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ a b West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Witzel, M. (2004). "[Extract: Kalash religion] The Ṛgvedic religious system and its central Asian and Hindukush antecedents". In Griffiths, A.; Houben, J.E.M. (eds.). The Vedas: Texts, language, and ritual (PDF). Groningen: Forsten. pp. 581–636. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Trainor 2004, p. 62.

- ^ a b Fowler, Merv (1999). Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-898723-66-0. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016.

- ^ Gowans, Christopher (2004). Philosophy of the Buddha: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-134-46973-4.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ Poopongpan, Waraporn (2007). "Thai kingship during the Ayutthaya period: A note on its divine aspects concerning Indra". Silpakorn University International Journal. 7: 143–171.

- ^ Holt, John Clifford; Kinnard, Jacob N.; Walters, Jonathan S. (2012). Constituting Communities: Theravada Buddhism and the religious cultures of south and southeast Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 45–46, 57–64, 108. ISBN 978-0-7914-8705-1.

- ^ Cowell & Davis 1969, pp. 5, 21.

- ^ Cowell & Davis 1969, p. 44.

- ^ Cowell & Davis 1969, p. 71 footnote 1.

- ^ Cowell & Davis 1969, p. 205.

- ^ Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ Sanskrit: Rigveda 5.34, Wikisource;

English Translation: Wilson, H.H. (1857). Rig-veda Sanhita: A collection of ancient Hindu hymns. Trübner & Company. pp. 288–291, 58–61. - ^ "Part 2 – Evening Chanting". www.Watpasantidhamma.org. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ a b Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013). From Stone to Flesh: A short history of the Buddha. University of Chicago Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-226-49321-3.

- ^ Dobbins, K. Walton (March–June 1968). "Two Gandhāran reliquaries". East and West. 18 (1–2): 151–162. JSTOR 29755217.

- ^ Indra's Net (book)#cite note-FOOTNOTEMalhotra20144-10

- ^ "Twelve heavenly deities (devas)". Nara, Japan: Nara National Museum. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Biswas, S. (2000). Art of Japan. Northern. p. 184. ISBN 978-81-7211-269-1.

- ^ Stutterheim, Willem Frederik; et al. (1995). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. xiv–xvi. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

- ^ Snodgrass, A. (2007). The Symbolism of the Stupa, Motilal Banarsidass. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 120–124, 298–300. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- ^ กรุงเทพมหานคร [Bangkok]. Royal Institute Newsletter (in Thai). 3 (31). December 1993. Reproduced in กรุงเทพมหานคร [Krung Thep Mahanakhon] (in Thai). Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Goswamy 2014, p. 245.

- ^ a b c Owen, Lisa (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. pp. 25–28, 29–33. ISBN 978-90-04-20629-8.

- ^ von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999). Jainism: An Indian religion of salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (2000) [1983]. "Iranian National History". The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3 (1). Cambridge University Press. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- ^ a b Malandra, W. W. (2004). "Indra". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mani, Vettam (1 January 2015). Puranic Encyclopedia: A comprehensive work with special reference to the epic and puranic literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0597-2.

- Goswamy, B.N. (2014). The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close encounters with 100 great works 1100-1900. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-08657-3.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton University Press.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road. Princeton University Press.

- Cowell, E.B.; Davis, Francis A. (1969). Buddhist Mahayana Texts. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-25552-1.

- Wilkings, W.J. (2001) [1882]. Hindu mythology, Vedic & Puranic (reprint ed.). Elibron Classics. ISBN 978-0-7661-8881-5. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

Reprint of original Thaker, Spink & Co., Calcutta, IN

- Masson-Oursel, P.; Morin, Louise (1976). "Indian Mythology". New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. New York, NY: The Hamlyn Publishing Group. pp. 325–359.

- Janda, M., Eleusis, das indogermanische Erbe der Mysterien (1998).

- Trainor, Kevin (2004). Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517398-7.

External links

[edit]- Lee, Phil. "Indra and Skanda deities in Korean Buddhism". Chicago Divinity School. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- "Indra, Lord of Storms and King of the Gods' Realm". Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- "Indra wood idol – 13th century, Kamakura period". Nara, Japan.

Indra

View on GrokipediaEtymology and nomenclature

Etymology

The name Indra derives from the Proto-Indo-European root h₃eid-, meaning "to swell," with a nasal infix forming i-n-d-rā-, an adjective denoting "powerful" or "vigorous," which aligns with associations of vitality, energy, and the swelling forces of storms in Vedic contexts.[5] This etymology underscores Indra's conceptual link to dynamic natural powers, such as the buildup of clouds and thunder, reflecting an ancient Indo-European motif of strength and renewal. Alternative reconstructions, such as Michael Janda's proposal of PIE *trikʷ-uel- ("smasher of the enclosure"), connect Indra more directly to his dragon-slaying myth.[6][5] Cognates in other Indo-European languages illustrate semantic divergences; in Avestan, the form Indra (or Andra) names a demon (daēwa) in Zoroastrian texts, contrasting sharply with the heroic Vedic deity and highlighting a shift from a positive, god-like figure to an antagonistic one in Iranian tradition due to theological reversals.[5] No direct cognates in Old Norse are securely attested in scholarly reconstructions, though broader Indo-European thunder-god parallels suggest shared vitality themes.[5] In Sanskrit, Indra is analyzed in Vedic compounds as possibly denoting "possessor of drops" (of rain), from indu ("drop") and -ra ("possessing"), as seen in Indrāṇi (Indra's consort, implying "possessor of Indra's drops"), evoking rain-bestowal, though this is a secondary semantic layer rather than the primary root.[7] Alternatively, it conveys "greatest" or "supreme" in contexts of power, aligning with its use as an intensifying epithet.[8] Linguistic evidence from the Rigveda treats Indra predominantly as a proper name for the principal storm god, invoked in over 250 hymns, yet the term also functions as a title or epithet (indra-, "the powerful one") applied to other deities like Agni or Soma, indicating an underlying nominal sense that could extend to multiple divine or heroic figures embodying strength.[9] This dual usage in early Vedic texts suggests Indra originated as a descriptive title before solidifying as a specific proper name.[9]Epithets and names in other languages

Indra is known by a multitude of epithets in Sanskrit Vedic literature, reflecting his multifaceted roles as a warrior deity and bringer of prosperity. Key among these are Śakra, meaning "the powerful one," which underscores his immense strength displayed in cosmic battles against demonic forces; Vṛṣan, denoting "bull-like" or "mighty," symbolizing his vigorous and virile prowess in combat; and Purandara, "fort-destroyer," derived from his legendary demolition of enemy strongholds during Vedic conflicts.[10] These epithets originate from descriptions of Indra's heroic exploits in the Rigveda, where he is portrayed as a triumphant warrior liberating waters and vanquishing adversaries like Vṛtra. Another prominent title, Maghavat, translates to "bountiful," highlighting his generosity in Vedic soma rituals, where he is invoked as a provider of abundance and rain.[10] The Rigveda attributes numerous epithets to Indra, categorized thematically to emphasize his attributes as a warrior, rain-bringer, and ritual patron. Warrior-themed epithets, such as Vṛtrahan ("slayer of Vṛtra") and Hari ("the yellow one," linked to his battle ferocity), portray him as an indomitable fighter wielding the vajra thunderbolt against chaos.[9] Rain-bringer epithets, including Meghavāhana ("he whose vehicle is the cloud") and Parjanya ("cloud-god"), connect him to storms and fertility, essential for agricultural prosperity in ancient Indo-Aryan society. Soma-related titles like Somapa ("soma-drinker") and Indu ("drop," referring to the ritual elixir) tie him to sacrificial ceremonies, where he is celebrated for empowering devotees through divine intoxication and victory.[11] These categories collectively illustrate Indra's dominance in over 250 hymns, more than any other deity, underscoring his central position in Vedic cosmology.[9] In regional Indian languages, particularly in ancient Tamil Sangam literature, Indra is referred to as Vendan, meaning "the king" or "chieftain," reflecting his sovereignty over the Marutam landscape, a fertile riverine region symbolizing pastoral and agricultural abundance.[12] This name appears in texts like the Tolkāppiyam, where Indra is honored through festivals like Indira Vizha, blending Vedic influences with Dravidian cultural contexts of kingship and seasonal rains.[13] Southeast Asian adaptations preserve Indra's essence through localized names integrated into Hindu-Buddhist traditions. In Thai mythology, he is known as Phra In, the "lord of heaven," depicted as ruler of the Tavatimsa realm in the Ramakien (Thai Ramayana), where he rides the three-headed elephant Erawan and intervenes in epic narratives to uphold dharma.[14] In Javanese culture, Bathara Indra serves as the god of thunder and war in wayang kulit shadow puppetry, drawn from Mahabharata stories, embodying celestial authority in performances that blend animist, Hindu, and Islamic elements.[15] Translations and phonetic adaptations appear in Buddhist texts across Asia, evolving from Sanskrit through regional phonologies. In Chinese Buddhist scriptures, Indra is transcribed as Yīnduóluó (因陀羅), a direct phonetic rendering of "Indra," or Dìshìtiān ("emperor release heaven"), emphasizing his role as Śakra, the deva king who protects the dharma; this transcription emerged during the Han dynasty translations, adapting Middle Indo-Aryan sounds to Sino-Tibetan phonetics for sutra propagation.[16] Parallels in Greek mythology draw Indra to Zeus, often called Dias ("of Zeus"), sharing traits as thunder-wielding sky gods who battle serpentine chaos (Typhon for Zeus, Vṛtra for Indra), rooted in common Proto-Indo-European storm deity archetypes.[17] These adaptations highlight Indra's enduring cross-cultural resonance as a sovereign force of order and elemental power.[18]Origins and characteristics

Historical origins

The deity Indra traces its roots to the Proto-Indo-Iranian period, where the name *Índras, reconstructed from roots associated with strength, represented a significant divine figure associated with power and strength.[19] In the Vedic tradition, this evolved into the heroic god Indra, celebrated as a protector and warrior who wields the thunderbolt (vajra) to battle chaos and release waters.[20] By contrast, in the Avestan tradition of ancient Iran, Indra appears as a malevolent daeva (demon), demonized during the Zoroastrian reforms that inverted the roles of earlier Indo-Iranian deities, transforming benevolent figures into adversaries of order.[20] This divergence highlights a schism in Indo-Iranian religious evolution around the 2nd millennium BCE, where shared mythological elements diverged based on theological priorities.[21] Comparative mythology reveals striking parallels between Indra and other Indo-European thunder deities, such as the Norse Thor and the Baltic Perkūnas, rooted in a common Proto-Indo-European heritage. Indra's battles against serpentine foes to liberate cattle and rains echo Thor's struggles with Jörmungandr and Perkūnas's confrontations with the devilish serpent, emphasizing motifs of storm gods as cattle-raiders and cosmic enforcers who ensure fertility through violent renewal.[18] These shared archetypes suggest a prehistoric Indo-European thunder god prototype, *Perkʷunos, whose attributes fragmented across migrating cultures, with Indra embodying the warrior aspect in the Indo-Iranian branch. Such comparisons underscore Indra's role not merely as a localized storm deity but as part of a broader pan-Indo-European mythological framework.[22] Archaeological evidence linking Indra to earlier South Asian cultures remains indirect, primarily through Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2500–1900 BCE) seals that depict motifs potentially evocative of storm and fertility symbols, such as battling figures or horned animals associated with later Vedic iconography.[23] These artifacts predate the Indo-Aryan migrations around 1500 BCE, during which Vedic-speaking groups are theorized to have entered the Indian subcontinent, blending with local traditions and formalizing Indra's cult in oral compositions that became the Rigveda.[24] Scholarly debates persist on Indra's precise nature—whether primarily solar, atmospheric, or martial—with French comparatist Georges Dumézil's trifunctional hypothesis positioning him firmly in the second function of sovereignty and warfare, akin to martial Indo-European heroes who protect society through force.[22] This framework interprets Indra's exploits as reflections of an archaic Indo-European social structure divided into priestly, warrior, and productive classes.[25]Iconography and attributes

In Hindu artistic traditions, Indra is commonly portrayed as a powerful, four-armed deity seated or standing astride his white elephant vahana, Airavata, symbolizing royal authority and celestial mobility. He wields the vajra, a thunderbolt weapon emblematic of his storm-bringing prowess, often in his primary right hand, while his other hands may hold a bow (sometimes identified as the rainbow, Indradhanu), a noose (pasha) for ensnaring foes, or an ankusha (elephant goad) for guiding Airavata. These depictions frequently incorporate atmospheric elements like storm clouds or rain motifs to underscore his role as the god of thunder and fertility, evolving from the more anthropomorphic warrior figures of early Vedic-inspired art to elaborate multi-limbed forms in later periods.[26][27][28] The rainbow, known as Indradhanu or "Indra's bow," serves as a prominent attribute, representing the arc of his weapon that bridges heaven and earth after storms, while a soma-drinking vessel occasionally appears in ritualistic contexts to evoke his invigorating consumption of the sacred elixir. In Puranic iconography, Indra's form advances to include thousand-eyed (sahasraksha) representations, as prescribed in texts like the Matsya Purana, where he is shown with multiple eyes across his body to signify omnipresent vigilance, departing from the singular, heroic physique of Vedic hymns. The vajra itself symbolizes indestructibility—likened to a diamond's hardness—and irresistible force, akin to lightning's penetrative power, tying into ritual uses without narrative elaboration.[29][30][31] Regional variations enrich Indra's visual legacy; in 12th-century Southeast Asian Khmer art at Angkor Wat, he is prominently featured atop his three-headed elephant vahana, Airavata, perched on the cosmic Mount Meru, embodying the temple's quincunx layout as the axis mundi and king of the devas. Medieval Indian sculptures, such as those from the Hoysala period, occasionally emphasize a bluish hue to his skin, evoking stormy skies, alongside accentuated multiple eyes or a third eye on the forehead for divine insight, as seen in temple friezes where he guards directional portals. These adaptations highlight Indra's enduring adaptability across artistic media, from stone carvings to paintings, while preserving core symbols of power and precipitation.[32][27]Role in Vedic literature

Hymns in the Rigveda

Indra emerges as the most prominent deity in the Rigveda, receiving the dedication of approximately 250 hymns solely addressed to him, alongside around 50 additional hymns shared with other gods, comprising nearly a quarter of the text's 1,028 hymns. These hymns underscore his central role in Vedic cosmology as the protector of cosmic order (ṛta) and in rituals, particularly those involving the consumption of soma, which invigorates his heroic deeds against chaotic forces.[9] Through repeated invocations, the poets portray Indra as the divine warrior who ensures the stability of the universe, rains, and fertility, making him indispensable to both natural phenomena and human prosperity.[33] The structure of Indra's hymns typically follows a tripartite pattern: initial praise (stotra) extolling his attributes and past victories, narration of mythological exploits to invoke his presence, and concluding invocations requesting aid, often tied to the soma ritual for enhanced potency. For instance, Rigveda 1.32 vividly recounts Indra's slaying of the dragon Vṛtra, depicting the thunder-wielding god piercing the serpent's hide to release imprisoned waters and cows, thereby restoring fertility and order to the world. Similarly, Rigveda 2.12 celebrates Indra's primordial birth as the foremost deity, emphasizing his unmatched strength in stabilizing the trembling earth and heavens through his valorous acts.[34] These compositions blend poetic imagery with ritual efficacy, using repetitive epithets like vṛtrahan (Vṛtra-slayer) to reinforce Indra's identity as derived from these very hymns.[9] Theologically, the hymns position Indra as the upholder of ṛta, the immutable cosmic law governing seasons, moral conduct, and natural cycles, which he defends by vanquishing demons that threaten disequilibrium.[35] Attributes such as "thousandfold strong" (sahasravidvan) recur over 50 times across the hymns, symbolizing his boundless power to amplify order and overwhelm adversaries. Scholarly analyses interpret Indra's frequent association with soma intoxication not as mere inebriation but as a divine enhancement that fuels his battles, transforming ecstatic rapture (mada) into martial supremacy, as evident in hymns where the pressed juice invigorates him for cosmic confrontations.[36] This portrayal reflects the Rigveda's integration of theology with ritual practice, where Indra's empowered state ensures the perpetuation of ṛta for the benefit of poets and sacrificers alike.[9]Myths and narratives in Vedic texts

In the Vedic prose texts, particularly the Brahmanas attached to the Samhitas, Indra's myths expand upon the poetic allusions in the Rigveda, portraying him as a heroic warrior whose deeds underpin cosmic order and ritual efficacy. These narratives emphasize Indra's role as Vṛtrahan, the slayer of the serpent-demon Vṛtra, who had withheld the primordial waters, causing drought and chaos. The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (1.6.3-4) recounts that Indra, armed with the thunderbolt (vajra) forged by the divine artisan Tvaṣṭṛ (later associated with Viśvakarman), confronts and shatters Vṛtra's mountainous body, releasing the captive rivers to flow freely and restoring fertility to the earth.[37] This act not only liberates the waters but also elevates Indra to kingship among the gods, symbolizing the triumph of order (ṛta) over obstruction, including the separation of heaven from earth.[38] Following the slaying, Indra experiences remorse and physical emaciation, as Vṛtra was the son of the Brahmin Tvaṣṭṛ, rendering the kill a brahmahatyā (sin of slaying a Brahmin). He conceals himself in remote realms, such as the earth or a lotus leaf floating on water, until the gods, led by Agni, locate him and restore his strength through offerings. In one variant, allies like the Aśvins and Viśvakarman aid in preparing the vajra, drawing from cosmic materials to ensure its indestructibility. These elements highlight Indra's vulnerability post-victory, underscoring themes of purification and renewal central to Vedic cosmology.[37][39] Other narratives in the Brāhmaṇas depict Indra's ongoing conflicts with Asuras (demons), portraying him as a relentless defender of the divine realm. For instance, in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, Indra battles the Asura Namuci, whom he decapitates using foam from the ocean as a weapon, avoiding direct blood-shed due to a vow. Similarly, accounts of Indra's role in creation emphasize his separation of heaven and earth through the slaying of Vṛtra, as elaborated in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa. A notable episode in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa describes the king Nahuṣa temporarily ascending to Indra's throne through ascetic power while Indra hides due to his sin, but Nahuṣa is humbled by divine intervention, restoring Indra's authority. These stories illustrate Indra's martial prowess and his function in maintaining boundaries between realms.[38][40] The myths are intrinsically linked to yajña (sacrificial) ceremonies, where Indra receives soma offerings to empower his victories. In the Brāhmaṇas, the preparation and libation of soma during rituals like the Agniṣṭoma reenact Indra's consumption of the elixir to gain strength against Vṛtra, with priests invoking him as the recipient of the central soma cup to ensure prosperity and ward off enemies. This ritual embedding transforms narrative exploits into performative acts, where the sacrificer's offerings mimic the gods' aid to Indra, fostering communal harmony and cosmic stability.[41] Variations across texts reveal a subtle decline in Indra's prominence in later Vedic layers. While the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa amplifies his heroic centrality, the Taittirīya Saṃhitā shifts focus toward ritual mechanics over mythic elaboration, with Indra's battles receiving briefer mentions amid expanded roles for other deities like Prajāpati, signaling a transition where his exploits become symbolic supports for sacrificial protocols rather than dominant themes.[9]Evolution in post-Vedic Hinduism

Depictions in epics and Puranas

In the Mahabharata, Indra is portrayed as the divine father of the hero Arjuna, born from Kunti's invocation, granting him celestial weapons and guidance during his exile and training in the heavens.[42] He tests the Pandavas' virtues, notably appearing as a crane (Yaksha) to question Yudhishthira in the Yaksha Prasna episode, evaluating dharma before revealing his identity and reviving the brothers.[42] During the Kurukshetra war, Indra intervenes on the Pandavas' behalf, such as by causing eclipses or providing divine aid, but his role underscores his flaws as a king prone to fear of curses, including those from sages for past transgressions like brahmanicide.[42] These depictions, appearing over 100 times across the epic, highlight Indra's moral ambiguities, such as adultery and vulnerability to demonic threats, diminishing his Vedic supremacy.[43] In the Ramayana, Indra's involvement is more peripheral, aiding Rama indirectly against Ravana by dispatching his charioteer Matali with a divine chariot during the Lanka battle, symbolizing celestial support for dharma.[42] However, myths reveal his vulnerabilities, such as his seduction of the sage Gautama's wife Ahalya, which curses him with a thousand eyes and exposes his ethical lapses, often retold to explain natural phenomena like starry markings.[42] This sidelined role contrasts with his Vedic prominence, positioning him as a subordinate ally rather than a central figure. The Puranas further expand Indra's character as the ruler of Svarga, managing celestial affairs across manvantaras, but increasingly as a jealous and flawed administrator under Vishnu's oversight, as in the Vishnu Purana (composed c. 3rd-5th century CE).[44] In the Bhagavata Purana (c. 9th-10th century CE), his envy peaks when the young Krishna diverts worship from him to Govardhana Hill, prompting Indra to unleash torrential rains; Krishna counters by lifting the hill for seven days, humbling Indra and affirming Krishna's supremacy.[44] Stories of adultery, such as with Ahalya, recur, alongside fears of curses that threaten his throne, portraying him as bureaucratically entangled and morally compromised.[44] Thematically, these texts mark Indra's evolution from a supreme Vedic warrior to a bureaucratic deity in post-Vedic Hinduism, with his interventions serving to elevate epic heroes and avatars while exposing his insecurities and ethical failings, over 100 references illustrating this diminished yet persistent authority.[43]Worship, rituals, and festivals

In Vedic rituals, Indra was a central recipient of offerings during Soma sacrifices, particularly in complex rites like the Agnicayana, where priests pressed and purified the Soma plant's juice as an oblation to invoke his favor for rain, fertility, and victory over adversaries.[45][46] These ceremonies, detailed in texts like the Yajurveda, involved chanting specific mantras from the Rigveda to summon Indra's thunderbolt-wielding presence, ensuring seasonal rains essential for agriculture.[2] However, with the rise of devotional traditions emphasizing Vishnu and Shiva in the post-Vedic period, such elaborate Indra-centric sacrifices declined sharply, as bhakti movements prioritized personal worship over Vedic fire rituals.[47] Puranic worship of Indra manifests primarily through icons and subsidiary shrines within larger Shaiva and Vaishnava temple complexes, rather than standalone temples, reflecting his diminished status as king of the gods. For instance, relief sculptures depicting Indra appear in 7th-century Pallava sites like Mamallapuram, where he is shown in assembly halls (sabhas) alongside other deities, symbolizing cosmic order. In South Indian traditions, such as at the Suchindram temple in Tamil Nadu, Indra is venerated through purification rites tied to his mythological atonement, integrated into broader temple iconography that highlights his role in divine hierarchies.[48] Festivals dedicated to Indra persist in specific regional contexts, blending Vedic invocations with local customs to celebrate his control over rain and prosperity. The Indra Jatra (Yenya), observed annually in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, since the Licchavi period (circa 4th-8th centuries CE), marks the end of the monsoon with chariot processions of the living goddess Kumari and masked dances portraying Indra's descent to earth for parijata flowers, thanking him for bountiful harvests.[49][50] In India, the Indra Mahotsava, referenced in ancient texts like the Atharvaveda and Mahabharata, commemorates Indra's victories.[51][52] In modern Hinduism, standalone worship of Indra remains rare, overshadowed by major deities, but he receives invocations during Vedic yajnas and as part of broader rituals addressing cosmic forces. In some tantric sects, Agamic mantras like "Om Indraya Namah" are recited to harness Indra's energy for protection and vitality. These practices underscore Indra's enduring, albeit ancillary, role in maintaining ritual continuity from Vedic to contemporary traditions.Indra in other religious traditions

In Buddhism

In Buddhism, Indra is adapted as Śakra (Pāli: Sakka), the ruler of the Trayastriṃśa heaven in Buddhist cosmology, where he functions as a devoted protector of the Buddha and the Dharma, subordinating his divine authority to the teachings.[53] The epithet Śakra, derived from Sanskrit meaning "the powerful one," directly connects this figure to the Vedic deity Indra while reinterpreting him as a guardian of moral order rather than a mere warrior god.[54] As Śakra-devānām-indra, or "Śakra, lord of the gods," he presides over the second heaven in the desire realm, intervening in key events to support the Buddhist path.[53] Buddhist texts depict Śakra's myths as illustrating his transition from Vedic independence to humble service under the Dharma, often showing him aiding the Buddha's life events. In the Pāli Canon, for instance, the enlightenment under the Bodhi tree is marked by an earthquake symbolizing cosmic rejoicing, with devas led by Śakra celebrating the Buddha's awakening and acknowledging the supremacy of enlightenment over heavenly rule.[55] Similarly, in narratives of the Buddha's descent from the Tuṣita heaven to teach his mother at Saṅkāśya, Śakra accompanies him, holding a jeweled umbrella to signify royal protection and homage to the Dharma.[56] These stories, drawn from texts like the Lalitavistara Sūtra and Divyāvadāna, portray Śakra testing disciples' virtue or entreating the Buddha to preach, emphasizing his role as a dharma guardian who models devotion for all beings.[53] Iconographically, Śakra retains Hindu attributes like the vajra thunderbolt and a cylindrical crown but incorporates Buddhist elements, appearing in early art as a princely figure in royal attire, often flanking the Buddha alongside Brahmā to form a protective triad. In Gandhāra art from the 1st to 5th centuries CE, he is carved in schist reliefs depicting scenes such as the Buddha's birth or first sermon, where his vajra symbolizes the indestructibility of the Dharma rather than martial prowess.[53] This evolution reflects a broader assimilation, transforming the Vedic storm god into a symbol of enlightened patronage. In Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, Śakra serves as an attendant to bodhisattvas, further embodying conversion to the bodhisattva path and the rejection of ego-bound divinity. The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, for example, features Śakra among the devas who receive teachings on mind-only doctrine, illustrating his full alignment with Mahāyāna ideals of compassion and non-duality. In Vajrayāna iconography and rituals, he appears in maṇḍalas as a dharmapāla, reinforcing his enduring role as a defender of the Buddha's legacy across Buddhist schools.[53]In Jainism