Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cuban solenodon

View on Wikipedia

| Cuban solenodon[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

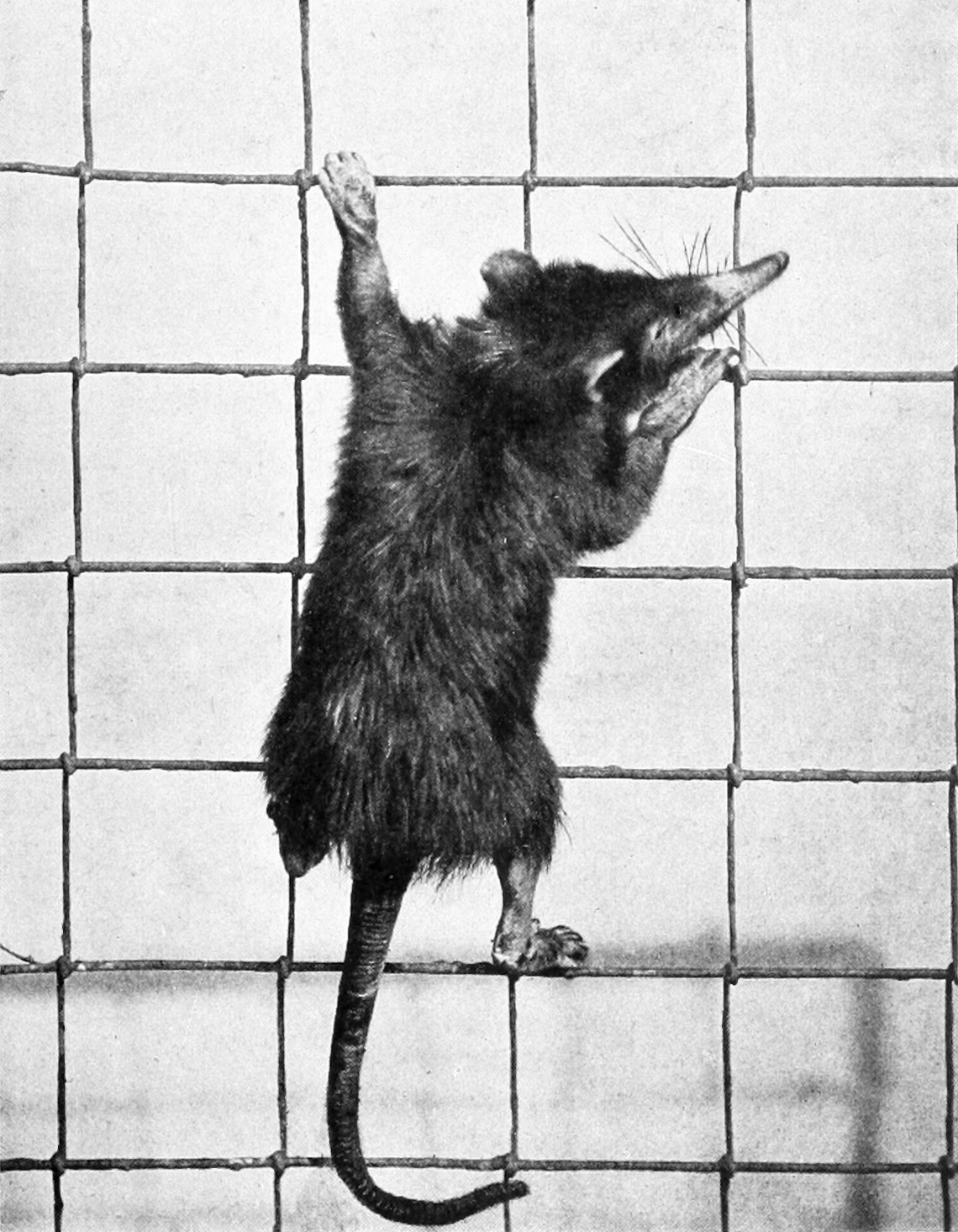

| Specimen at the Bronx Zoo, 1913 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Eulipotyphla |

| Family: | Solenodontidae |

| Genus: | Atopogale Cabrera, 1925 |

| Species: | A. cubana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Atopogale cubana (Peters, 1861)

| |

| |

| Cuban solenodon range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Cuban solenodon or almiquí (Atopogale cubana) is a small, furry, shrew-like mammal endemic to mountainous forests on Cuba. It is the only species in the genus Atopogale. An elusive animal, it lives in burrows and is only active at night when it uses its unusual toxic saliva to feed on insects. The solenodons (family Solenodontidae), native to the Caribbean, are one of only a few mammals that are venomous.

The Cuban solenodon is endangered and was once considered extinct due to its rarity. It and the Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) are the only surviving solenodon species; the others are extinct.

Taxonomy

[edit]Although formerly classified in the genus Solenodon, phylogenetic evidence supports it being in its own genus, Atopogale.[3]

Rediscovery

[edit]

Since its discovery in 1861 by the German naturalist Wilhelm Peters, only 36 had ever been caught. By 1970, some thought the Cuban solenodon had become extinct, since no specimens had been found since 1890. Three were captured in 1974 and 1975, and subsequent surveys showed it still occurred in many places in central and western Oriente Province, at the eastern end of Cuba; however, it is rare everywhere. Prior to 2003, the most recent sighting was in 1999, mainly because it is a nocturnal burrower, living underground, and thus is very rarely seen. The Cuban solenodon found in 2003 was named Alejandrito. It had a mass of 24 oz (0.68 kg) and was healthy. It was released back into the wild after two days of scientific study were completed.

Appearance

[edit]With small eyes, and dark brown to black hair, the Cuban solenodon is sometimes compared to a shrew, although it most closely resembles members of the family Tenrecidae of Madagascar. It is 16–22 in (41–56 cm) long from nose to tail-tip and resembles a large brown rat with an extremely elongated snout and a long, naked, scaly tail.

Status

[edit]Willy Ley wrote in 1964 that the Cuban solenodon was, if not extinct, among "the rarest animals on earth".[4] It was declared extinct in 1970, but was rediscovered in 1974. Since 1982, it has been listed as an endangered species, in part because it only breeds a single litter of one to three in a year (leading to a long population recovery time), and because of predation by invasive species, such as small Indian mongooses, black rats, feral cats, and feral dogs. The species is also thought to be threatened by deforestation as well as habitat degradation due to logging and mining. However, there is very little conservation attention given to the species.[5]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]It is endemic to mountainous forests in the Nipe-Sagua-Baracoa mountain range of eastern Cuba, in the provinces of Holguín, Guantánamo, and Santiago de Cuba, though subfossil evidence showed it once inhabited throughout the island. It is nocturnal and travels at night along the forest floor, looking for insects and small animals on which to feed.

Behavior

[edit]This species has a varied diet. At night, they search the forest floor litter for insects and other invertebrates, fungi, and roots. They climb well and feed on fruits, berries, and buds, but have more predatory habits, too. With venom from modified salivary glands in the lower jaw, they can kill lizards, frogs, small birds, or even rodents. They seem not to be immune to the venom of their own kind, and cage mates have been reported dying after fights.

Mating

[edit]

Cuban solenodons only meet to mate, and the male practices polygyny (i.e. mates with multiple females). The males and females are not found together unless they are mating. The pair will meet up, mate, then separate. The males do not participate in raising any of the young.

References

[edit]- ^ Hutterer, R. (2005). "Order Soricomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Kennerley, R.; Turvey, S.T. & Young, R. (2018). "Atopogale cubana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T20320A22327125. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T20320A22327125.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Atopogale cubana (W. Peters, 1861)". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Ley, Willy (December 1964). "The Rarest Animals". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- ^ "Cuban Solenodon". EDGE of Existence.

External links

[edit]- Archived 2009-10-31

- EDGE of Existence "(Cuban solenodon)" Saving the World's most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species