Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bad Muskau

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

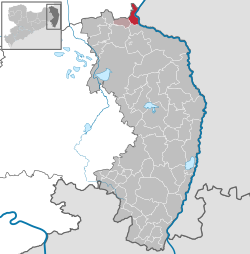

Bad Muskau (German pronunciation: [ˌbaːt ˈmʊskaʊ] ⓘ) or Mužakow (Upper Sorbian pronunciation: [ˈmuʒakɔf] ⓘ; named Muskau in German until 1962; Polish: Mużaków; Czech: Mužakov) is a spa town in the historic Upper Lusatia region in eastern Germany, at the border with Poland. It is part of the Görlitz district in the State of Saxony.

Key Information

It is located on the banks of the Lusatian Neisse river, directly opposite the town of Łęknica. It is part of the recognized Sorbian settlement area in Saxony. Upper Sorbian has an official status next to German, with all villages bearing names in both languages.

Bad Muskau gained worldwide fame through prince and landscape artist Hermann von Pückler-Muskau, who created a unique cultural asset with his landscape park. The Muskau Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is split between Bad Muskau and Łęknica.

History

[edit]

Muskau (Sorbian, "men's town") was founded in the 13th century as a trading center and defensive location on the Neisse, being first mentioned in a document in 1249. The state country (Standesherrschaft) of Muskau was the largest of the Holy Roman Empire. From 1319 it was part of the Duchy of Jawor, one of Lower Silesian duchies of fragmented Piast-ruled Poland.[3][4] In 1329 it passed to the Bohemian (Czech) Kingdom, where it formed part of the Margraviate of Upper Lusatia, a Bohemian (Czech) Crown Land.[5] The town passed into the possession of the von Bieberstein family in 1447, gaining its charter in 1452.[5] Part of the von Bieberstein crest, the red five-pointed stag horn, remains in the town's coat of arms.

By the 1635 Peace of Prague it passed to the Electorate of Saxony, later elevated to the Kingdom of Saxony in 1806. Between 1697 and 1763, it was also under the rule of Polish kings in personal union and one of two main routes connecting Warsaw and Dresden ran through the town at that time.[6] Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland often traveled that route. In 1815, the northern and eastern parts of Upper Lusatia came to Prussia as a result of the Congress of Vienna, which reorganized the political order of Europe after the Coalition Wars (1792–1815) and from then on bore the official name "Prussian Upper Lusatia". Administratively, this area was integrated into the Province of Silesia and later into the Province of Lower Silesia, which existed until 1945.

In the so-called "Zornfeuer" of 1766, the city burned down completely; Only the town church and the castle on the Burglehn were spared. During the withdrawal of the Napoleonic army from Russia in 1813, Württemberg cuirassiers brought a typhus epidemic to Muskau, which killed around a fifth of the population. The inhabitants lived (with a few exceptions) in the status of hereditary subservience, which only ended after 1815 under Prussian rule.

Due to the rich clay deposits, a strong pottery trade developed in Muskau. During its heyday from the 17th to the middle of the 19th century, up to 20 masters settled in the southern suburb of the town, the Schmelze (today Schmelzstrasse).

The first documented mention of alum mining in the town of Muskau comes from 1573. The alum hut, laid out on the site of today's bathing park, was once one of the oldest in Saxony, along with the huts in Reichenbach, Schwemsal and Freienwalde. Alum mining stopped in 1864.

In the 19th century, lignite was mined in the area between Muskau and Weißwasser.

Until the beginning of the 19th century Muskau's direct rulers were the Counts of Callenberg, succeeded up to 1845 by Count (later Prince) Hermann von Pückler-Muskau, later on by Prince Wilhelm Friedrich Karl von Oranien-Nassau, and after him by the Counts von Arnim, right up to their flight in April 1945.

In 1940, the modern separate town of Łęknica as incorporated into Bad Muskau as Lugknitz, before it was separated in 1945.[7]

Towards the end of the Second World War, the city was severely damaged by artillery fire from the Soviet Army, which was pushing over the Neisse, and by the 2nd Polish Army. After World War II, the town was divided along the Neisse River between East Germany and Poland. About two thirds of the park came under Polish administration. In Autumn 1945, the castle and large parts of the city fell victim to a fire. In July 1945, Count von Arnim received the notification that “class rule and all businesses had been seized without compensation." Muskau was largely rebuilt with the exception of the town church, the Sorbian St. Andrew's Church, and the town hall. The town church was blown up in April 1959.[8]

In 1962 Muskau was renamed "Bad Muskau" (spa town Muskau), with the construction of a sanatorium on the site of brine source. In 1972 the border crossing between East Germany and Poland was opened[5] and visa-free local border traffic was allowed.[7]

Sorbs still make up a large portion of the population, with the Muskau dialect spoken in and around the town.

Governance

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- Nathaniel Gottfried Leske (1751–1786), natural scientist and geologist

- Leopold Schefer (1784–1862), writer and composer

- Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785–1871), famous landscape gardener and writer, founder of the Park von Muskau

- Gustav Fechner (1801–1887), experimental psychologist

- Eduard Petzold (1815–1891), landscape gardener

- Alwin Schultz (1838-1909), art and cultural historian

- Paul Kraske (1851–1930), surgeon

- Bruno von Mudra (1851-1931), General of Infantry and freeman of Muskau

- Werner Richter (1888-1969), writer

- Erna Pfitzinger (1898–1988), potter

- Karl Peglau (1927-2009), traffic psychologist, inventor of the East German Ampelmännchen for traffic lights

- Olaf Zinke (1966), skater, Olympic gold medalist

- Tim Kleindienst (1995), soccer player

In addition, a number of professional hockey players were born in Bad Muskau:

- Ronny Arendt (born 1980)

- Frank Hördler (born 1985)

- Ivonne Schröder (born 1988)

- Elia Ostwald (born 1988)

- Toni Ritter (born 1990)

References

[edit]- ^ Wahlergebnisse 2019, Freistaat Sachsen, accessed 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2023" (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Knothe, Hermann (1879). Geschichte des Oberlausitzer Adels und seiner Güter (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. p. 567.

- ^ Köhler, Gustav (1846). Der Bund der Sechsstädte in der Ober-Lausitz: Eine Jubelschrift (in German). Görlitz: G. Heinze & Comp. p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Stadtgeschichte". Stadt Bad Muskau (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Informacja historyczna". Dresden-Warszawa (in Polish). Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Grenzstadt". Stadt Bad Muskau (in German). Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Kirchensprengung und -abriss in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik" [Church demolition and demolition in the German Democratic Republic] (in German). 21 December 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

External links

[edit]Bad Muskau

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and borders

Bad Muskau is located at 51°33′00″N 14°43′01″E in the historic Upper Lusatia region of eastern Germany.[9] It forms part of the state of Saxony and the Görlitz district, encompassing an area of 15.38 km². The town is positioned directly on the banks of the Lusatian Neisse river, which serves as the natural border with Poland and separates Bad Muskau from the Polish town of Łęknica.[10] This river boundary highlights the town's role in the transboundary landscape, with features like Muskau Park extending across both sides.[11] Bad Muskau lies approximately 50 km west of Görlitz, the district seat, and 170 km southeast of Berlin, providing convenient access to major urban centers in the region.[12] As a designated Sorbian settlement area in Saxony, it maintains bilingual signage in German and Upper Sorbian to reflect its cultural heritage.[13]Landscape and environment

Bad Muskau lies at an elevation of approximately 110 meters above sea level, situated in the lowlands of the Lusatian Neisse valley. The town is part of the transboundary UNESCO Global Geopark Muskauer Faltenbogen / Łuk Mużakowa, covering 578.8 km² and focusing on the glacial moraine landscapes formed during the Elster Ice Age around 340,000 years ago.[14][15] The terrain consists of flat to gently rolling landscapes, characterized by broad flood terraces, meadows, and swampy grounds along the riverbanks, interspersed with morainic plateaus featuring mild slopes of 5-10%. This glacial-influenced topography, part of the Muskauer Belt—a horseshoe-shaped moraine formation—includes subtle elevations up to around 160 meters in surrounding hills, creating a mosaic of open fields, woodlands, and wetlands that support diverse ecological processes.[16][17] The hydrology of the area is dominated by the Lusatian Neisse River, which flows meridionally through the valley with a gentle lower-course slope of 0.63%, forming a mountainous-type watercourse prone to periodic flooding that reaches 105.5-107 meters above sea level during centennial events. Minor tributaries and artificial channels, such as drainage ditches and reservoirs, contribute to the local water network, influencing groundwater depths that vary from 1 to 120 meters and maintaining wetland ecosystems resilient to temporary inundation. These hydrological features shape the valley's ecology by fostering riparian zones rich in alder and willow vegetation.[16] The landscape integrates into the broader Oberlausitzer Heide- und Teichlandschaft UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, established in 1996 and encompassing over 30,000 hectares of protected heath, pond, and forest areas to promote sustainable development and biodiversity conservation. This designation underscores Bad Muskau's role in regional biodiversity, hosting diverse habitats such as oak-hornbeam and beech forests, floodplain meadows, and wetlands that support 102 bird species, 10 amphibian species, and 6 reptile species, alongside rare flora like Galium rotundifolium and ancient oaks up to 700 years old. Conservation efforts within the reserve focus on natural succession, meadow restoration, and pollution reduction to preserve these biotopes.[18][16]History

Foundation and medieval period

The origins of Bad Muskau trace back to the mid-13th century, amid the broader process of German eastward settlement (Ostsiedlung) in Upper Lusatia, where settlers established villages alongside the indigenous Sorbian population. The Sorbian communities, descendants of earlier Slavic tribes like the Milzeners, formed a foundational ethnic layer in the region, contributing to its cultural and linguistic diversity from the outset.[19] The settlement was first documented in 1253 under the name Muscove, with the name evolving to Muskau. This period coincided with intensified colonization under Bohemian influence, as Upper Lusatia fell under the Kingdom of Bohemia's control in the 12th century, encouraging agricultural expansion and land clearance by German farmers.[2] From 1319, the area became part of the Duchy of Jawor, one of the fragmented Silesian principalities, before its transfer to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1329, integrating it into the larger Margraviate of Lusatia. This shift solidified its position within Bohemian administrative structures, fostering stability for local development. By the 15th century, Bad Muskau had evolved into a primarily agricultural settlement, reliant on farming and forestry, while its strategic location along emerging trade routes in Upper Lusatia began to support modest commerce. In 1452, Wenzel von Biberstein granted it town rights on September 21, empowering local craftsmen, brewers, and merchants through privileges for markets and guilds, which hinted at an economy transitioning toward urban trade activities.[2][20]Early modern and 19th century

In the early 17th century, during the Thirty Years' War, the region encompassing Bad Muskau, part of Upper Lusatia, was transferred to the Electorate of Saxony through the Peace of Prague in 1635, marking a shift from Bohemian control to Saxon administration.[19][21] This integration into Saxony stabilized local governance amid the war's devastation, allowing for gradual economic recovery under electoral oversight.[19] Economic activity in Bad Muskau during this period centered on resource extraction and craftsmanship, with alum mining emerging as a key industry. The first documented alum mining in the town dates to 1573, exploiting local deposits of this double salt, which was vital for dyeing, leather tanning, and glassmaking; operations continued until 1864, primarily in the hills now part of the town's landscape park.[21] Complementing this, the pottery sector experienced significant growth from the 17th to 19th centuries, fueled by abundant local clays; the establishment of the first potters' guild in 1596 formalized the trade, leading to production of everyday ceramics, bricks, and industrial containers that supported regional manufacturing.[21] By the mid-19th century, lignite mining was introduced, with the Felix Mine opening in 1851 and further operations like the Hermann Mine commencing around 1878, providing fuel for emerging industries and transforming the local economy amid industrialization.[21] In 1811, Hermann von Pückler-Muskau inherited the Muskau estate, a vast Standesherrschaft spanning over 125,000 acres, which included the town and surrounding villages, granting him significant autonomy as lord.[22][23] Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the territory was ceded from the Kingdom of Saxony to Prussia, yet Muskau retained its status as a princely estate under Pückler, preserving its semi-sovereign character within the Prussian framework.[21][16] Pückler's tenure until 1845 highlighted cultural ambitions, including the initiation of a landscape park project as a culminating feature of the era's developments.[24]20th and 21st centuries

During World War II, Bad Muskau experienced severe destruction as the front line advanced through the Muskau Neisse Valley in the war's final months. Approximately 80% of the town was devastated by bombing and ground fighting, including all bridges spanning the Neisse River and significant portions of the historic park landscape. The Old Castle was completely destroyed, while the New Palace was set ablaze on April 30, 1945—likely by arson—and left as a ruin, with the park's structures and paths also heavily impacted.[6][1][25] Following the war's end in 1945, the Potsdam Agreement established the Oder-Neisse line as the German-Polish border, bisecting Bad Muskau and its renowned park along the Neisse River. The western section, including most of the town and two-thirds of the park, remained under East German (GDR) administration, while the eastern part came under Polish control and was largely neglected, becoming overgrown under forestry management. This division rendered the river an impassable barrier, severing the park's unified design and limiting access for decades.[6][1][26] In the GDR era, Bad Muskau was renamed "Bad Muskau" in 1961 to emphasize its emerging status as a spa town, coinciding with the construction of a sanatorium over a local brine spring to promote health tourism. This development built on earlier 19th-century traditions but aligned with socialist efforts to revitalize border regions through wellness infrastructure.[20][27] German reunification in 1990 spurred comprehensive restoration initiatives, including the 1992 transfer of the German park portion to Saxony state ownership and a 1988 German-Polish agreement in Zielona Góra to jointly rehabilitate the divided park by rebuilding bridges, clearing overgrowth, and restoring pathways. The New Palace, a ruin since 1945, underwent reconstruction starting in 1995, completed in 2013 at a cost of around 25 million euros. In 2004, Muskau Park was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a rare transboundary site, recognizing its integrated landscape design across the border. More recently, the discovery of a thermal brine spring in 2000 at a depth of 1,600 meters has driven spa tourism growth, with official recognition as a state healing source in 2010 supporting modern facilities like brine baths and wellness centers. The town's population stabilized around 3,577 in 2023 after decades of post-war decline, aided by tourism and cross-border cooperation.[6][1][26][28][27][29][30]Administration

Local governance

Bad Muskau is a town (Stadt) in the Görlitz district (Landkreis Görlitz) of the Free State of Saxony (Freistaat Sachsen), Germany. It functions as the administrative seat of the Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Bad Muskau, a municipal association (Verwaltungsgemeinschaft) that coordinates intermunicipal services, including planning, infrastructure, and administrative support, among Bad Muskau and the nearby community of Gablenz.[31] The town is led by a full-time mayor (Bürgermeister), who serves as the head of the administration and chairs the town council. The current mayor is Thomas Krahl of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), who was elected in September 2019 with 890 votes and holds office for a seven-year term ending in 2026.[32][33] As mayor, Krahl oversees executive functions, including budget implementation and policy enforcement, while representing the town in regional and state matters. The town council (Stadtrat) constitutes the legislative body, responsible for approving budgets, ordinances, and major decisions on local development. Comprising 16 members, the council is elected every five years through a proportional representation system open to all eligible voters aged 16 and older, as stipulated by the Saxon Municipal Code (Sächsische Gemeindeordnung, SächsGemO §§ 36–48).[34] The most recent election occurred on June 9, 2024, resulting in a diverse composition that includes the CDU as the largest faction with 6 seats, alongside the Alternative for Germany (AfD) with 5 seats securing a deputy mayor position, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) with 3 seats, the Free Voters (FW) with 1 seat, and the Left (Die Linke) with 1 seat.[35][36] Council meetings occur approximately every four weeks, with public access to agendas and protocols via the town's information system.[37] Bad Muskau's designation as a spa town ("Bad") was officially granted in 1961 following the development of therapeutic brine baths, reflecting its natural saline springs and supporting a focus on health-oriented governance.[2] This status, regulated under German state healing bath laws (Heilbadegesetze), enables targeted local policies such as subsidies for spa infrastructure, zoning protections for wellness facilities, and integration of health tourism into urban planning to promote sustainable economic growth.Town twinning and international relations

Bad Muskau maintains formal town partnerships with several municipalities, primarily to promote cultural exchange, historical reconciliation, and cross-border collaboration. Its closest partner is Łęknica in Poland, established in 2003, reflecting their shared history as a single settlement until the post-World War II border division along the Lusatian Neisse River, which bisects the UNESCO-listed Muskauer Park. This partnership facilitates joint management of the park, including restoration efforts and tourism promotion, as well as regular cultural events and youth exchanges to strengthen community ties.[38][39] Additional partnerships include Bolków in Poland, formalized in 2006, which emphasizes mutual understanding through visits, joint projects in environmental protection, and cultural programs, building on broader German-Polish reconciliation efforts. Within Germany, Bad Muskau has a longstanding friendship with Balve in North Rhine-Westphalia, supported since the late 20th century by associations such as choral groups and shooting guilds, focusing on social and traditional exchanges.[38][40][38] As a border town, Bad Muskau participates actively in the Euroregion Spree-Neiße-Bober (also known as Neisse-Nisa-Nysa), an organization founded in 1991 to foster transboundary cooperation across Germany, Poland, and Czechia along the Neisse River. This involvement supports park management through shared planning, research exchanges, and cultural initiatives, such as the "Learning and Working across Borders" program launched in 1998, which employs bilingual youth in restoration projects. The Euroregion framework also enables Sorbian-Polish cultural ties, incorporating the town's Sorbian heritage into governance dialogues on minority languages and traditions during joint events.[41][16] Post-German reunification in 1990, Bad Muskau has benefited from EU funding for transboundary projects, particularly through programs like PHARE and INTERREG, which have supported the Muskauer Park's revival. For instance, a 1994 PHARE grant of 495,400 PLN aided Polish-side restoration, while German efforts received over 7 million DM from federal and state sources by 2001, with costs often shared equally across the border to ensure integrated development. These initiatives, coordinated via a bilateral working group since 1992, have restored key features like the Neisse bridges and promoted sustainable tourism as a model of European reconciliation.[16][42]Demographics and society

Population trends

As of 31 December 2023, Bad Muskau had a population of 3,605 residents.[3] As of 31 December 2024, the population was 3,577.[43] The town's population density stands at approximately 232 inhabitants per square kilometer, calculated over its 15.38 km² area.[44] This reflects a compact settlement pattern influenced by its location along the German-Polish border and the surrounding Muskau Park. Historically, the population peaked at around 5,000 in the late 1930s, with 5,025 recorded in 1939.[45] Following World War II, numbers declined sharply from a temporary high of 5,910 in 1946—likely due to postwar refugee influxes—to about 4,255 by 1990, driven by the Oder-Neisse line border division in 1945 that bisected the town and its key landscapes, disrupting local economy and prompting out-migration.[45] Regional lignite mining activities in Lusatia further contributed to this postwar depopulation through environmental and economic pressures.[46] Since German reunification in 1990, the decline has stabilized at a slower rate, dropping to 3,691 by 2011 and 3,669 by 2021, with projections indicating a further gradual decrease to around 3,300–3,500 by 2040 under varying demographic scenarios.[47] The population exhibits an aging structure, with 29.5% of residents aged 65 or older in 2021, compared to 17.8% under 20 and 52.7% in the working-age group of 20–64.[47] This trend underscores a maturing demographic, with the average age rising over time. Some counterbalancing migration occurs, including a modest influx tied to tourism drawn by the UNESCO-listed Muskau Park, which supports seasonal and occasional permanent relocations. The Sorbian ethnic proportion serves as a stabilizing cultural factor in these trends.[47]Ethnic and linguistic composition

Bad Muskau is part of the officially recognized Sorbian settlement area in Saxony, as defined by the Sächsisches Sorbengesetz of 1999, which encompasses communities in the Niederschlesischer Oberlausitzkreis including the town and its surrounding parishes.[48] The Sorbian community, primarily ethnic Upper Sorbs, forms a notable minority, with an average share of approximately 12% of the total population in the local Sorbian settlement communities.[49] The Muskau dialect (Mužakowski dialekt) represents a unique transitional variant of Upper Sorbian, bridging eastern Upper Sorbian features with influences from Lower Sorbian and local border dynamics; it is characterized by distinct phonological and lexical traits, such as softened consonants and vocabulary borrowings reflective of the region's historical multilingualism.[50] This dialect is spoken in Bad Muskau and adjacent villages, contributing to the linguistic diversity of the Upper Lusatian border area.[51] Bilingual policies are enshrined in the Sorbengesetz, mandating the official use of German and Upper Sorbian in public signage, such as street names and official buildings, throughout the settlement area; in education, Sorbian is offered as a medium of instruction in local schools where demand exists, and citizens may use Upper Sorbian in interactions with authorities and courts with equal legal validity to German.[48] These measures support the preservation of Sorbian linguistic rights in daily and institutional contexts. Following World War II, the establishment of the Oder-Neisse line as the German-Polish border in 1945 profoundly influenced ethnic dynamics in Bad Muskau, dividing longstanding Sorbian communities and the Muskau Park itself between Germany and Poland, while population expulsions and resettlements of Germans from former eastern territories reduced the relative proportion of Sorbs through demographic shifts and assimilation pressures. This border reconfiguration disrupted cross-border Sorbian ties and contributed to a gradual decline in the community's linguistic vitality amid broader regional migrations.[52]Economy and infrastructure

Historical industries

Bad Muskau's economy in its early history was fundamentally agricultural, with medieval farming practices supporting the local population and the feudal estate centered around Muskau Castle. The region, part of Upper Lusatia, relied on crop cultivation and livestock rearing typical of the area's fertile soils, which formed the backbone of sustenance and trade until the rise of industrial activities. By the early modern period, agricultural production transitioned toward large-scale estate management under noble ownership, including the Counts of Muskau, who oversaw farms and outbuildings that integrated with the surrounding landscape. Pottery production emerged as a major industry from the 17th to the 19th centuries, leveraging abundant local clay deposits to create stoneware and ceramics, including Muskau stoneware known for its durability and aesthetic appeal. The potters' guild, founded in 1596, oversaw up to 22 workshops concentrated near the current park area, producing household goods, bricks, and decorative items that were exported across Lusatia, Bohemia, and beyond. Firms like the Tonwarenfabrik Carl Lehmann, established in 1794, and the Deutsche Ton- und Steinzeugwerke AG exemplified this sector's growth, contributing significantly to the town's economic identity before declining in the late 19th century due to competition from industrialized production elsewhere.[53][54][55] Mining operations played a pivotal role in the town's development, beginning with alum extraction documented from 1573 to 1864, when large deposits of the mineral—often found in clay layers above lignite seams—were processed in an alum hut on the site of the modern bathing park. Muskau alum, a key double salt used in dyeing, leather tanning, and medicine, was exported to regions including Bohemia and Russia, bolstering local wealth under princely oversight. In the 19th century, lignite coal mining expanded rapidly, with operations extracting the resource from open pits and shafts between Muskau and nearby Weißwasser; this industry peaked amid Prussian economic policies promoting resource exploitation but began waning toward century's end due to environmental degradation and shifting market demands.[21][56] The origins of Bad Muskau's spa tradition trace to pre-1961 utilization of mineral springs, particularly brine sources linked to historical alum processing, which were employed for therapeutic bathing and health treatments as early as the 19th century. These springs, rich in salts from the mining legacy, attracted visitors seeking relief from ailments through hydrotherapy, laying the groundwork for the town's later designation as a spa in 1961 with the construction of a sanatorium.[2][21]Modern economy and transport

Since German reunification in 1990, Bad Muskau's economy has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from heavy reliance on state-owned industries to tourism and related services as the primary drivers of growth. The closure of major facilities, such as the Muskauer Hohlglas-Hüttenwerke glassworks in 1990 and the Fein- und Zigarettenpapierfabrik paper mill in 2000, marked the end of traditional manufacturing dominance, leading to significant job losses in the early post-reunification years. Today, tourism, bolstered by the UNESCO-listed Muskau Park and the town's spa heritage (Kurwesen), along with gastronomy and hospitality, forms the cornerstone of the local economy, employing a substantial portion of residents through the Fürst-Pückler-Park Foundation and associated businesses.[5][57] Small-scale manufacturing persists in a modest industrial park on Heideweg, hosting various producing enterprises alongside niche operations like a local sawmill, brewery, and the historic Stegler cigar factory, contributing to diversified but limited industrial activity. Spa services, leveraging the town's natural mineral springs and wellness facilities, complement tourism as a key sector, attracting visitors seeking therapeutic treatments and reinforcing Bad Muskau's identity as a health resort. This post-1990 pivot has stabilized the economy, with services and trade now the most important commercial branches.[5][57] Transportation infrastructure supports this service-oriented economy by facilitating access for tourists and cross-border trade. The town is connected by the B115 federal road, linking it directly to Görlitz in the east and, via the B156 from the A4 motorway, to Dresden and Bautzen in the west, enabling efficient road travel from major regional hubs. Rail connectivity relies on the Dresden–Görlitz line, with services to nearby Weißwasser station followed by bus line 80 into Bad Muskau, providing reliable links for commuters and visitors.[58][59] Border transport enhances accessibility to Poland, with the Neisse River bridges—particularly the Postbrücke connecting Bad Muskau to Łęknica—serving as key crossings for pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles, fostering economic ties in the Euroregion. Extensive cycling paths, including the Oder-Neiße-Radweg (EuroVelo 12), integrate Bad Muskau into a broader network of border-spanning routes, promoting sustainable tourism and regional mobility. Post-reunification unemployment spiked due to industrial closures, mirroring broader Lusatian trends with over 80,000 mining-related job losses across the region, but has since declined as tourism absorbed much of the workforce, with services now employing the majority.[60][61][51]Culture and tourism

Muskau Park and Castle

Muskau Park, covering 559.9 hectares and straddling the German-Polish border along the Lusatian Neisse River, exemplifies an English-style landscape garden designed by Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau from 1815 to 1844. Pückler, a pioneering landscape architect, drew inspiration from English gardens to create a harmonious blend of natural scenery, artificial lakes, winding paths, and strategic viewpoints, with assistance from horticulturist Eduard Petzold in later phases. The park's layout emphasizes picturesque compositions, including meadows, woodlands, and water features that guide visitors through varied terrains.[1][62] In 2004, Muskau Park was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a transboundary cultural landscape, meeting criteria (i) and (iv) for its role as an exceptional example of 19th-century European park design that influenced landscape architecture across Europe and America. The site's unique division by the Neisse River, which forms the international border, highlights its cross-cultural significance, with about one-third in Germany and the rest in Poland. Post-1990 restoration efforts, coordinated by the Stiftung Fürst-Pückler-Park Bad Muskau founded in 1993, revived neglected areas following decades of division during the Cold War.[1][63] The New Castle (Neues Schloss), situated in the German portion of the park, anchors the landscape as its primary architectural element. Its origins trace to a 16th-century Renaissance palace built atop a medieval moated castle, but the present three-wing complex in neo-Renaissance style was constructed in the 19th century under Pückler's successors, including Friedrich, Prince of the Netherlands. Severely damaged by arson in 1945 near the end of World War II, the castle remained a ruin for decades until systematic reconstruction began in the 1990s, culminating in the restoration of its interiors and structure by 2013.[63][64] Key architectural features of the castle and park include the Schlossrampe, a ramp designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel to link the building to the park's pleasure grounds, and opulent interiors such as the grand ballroom with its high ceilings and unplastered walls evoking historical grandeur. The park boasts neoclassical and Gothic Revival pavilions, like the rebuilt Blue Bridge spanning the Neisse and the Orangery, which frame scenic vistas and integrate the castle into the surrounding gardens. These elements underscore the park's design philosophy of uniting architecture with nature in a cohesive artistic whole.[1][64]Sorbian heritage and events

The Sorbian community in Bad Muskau upholds a rich array of traditions that reflect their Slavic roots in Upper Lusatia. A key custom is the decoration of Easter eggs, referred to as pisanice or kraslice, employing the ancient wax-resist technique to etch vibrant patterns symbolizing fertility, protection, and renewal.[65] Another enduring tradition is the Birds' Wedding (Ptašanske swadźba), a spring ritual enacted by children dressed in feathered costumes to mimic a avian marriage ceremony, invoking blessings for bountiful harvests and warding off winter's ills. This pre-Christian-derived custom, symbolizing harmony between humans and nature, is upheld by the Sorbian community in the region.[65] Annual events vividly showcase these traditions, drawing both locals and visitors to immerse in Sorbian culture. Easter markets in the Muskau area feature live demonstrations of egg decorating by artisans, alongside performances of traditional music on instruments like the dudy (bagpipes) and lively group dances in embroidered costumes, fostering community bonds and cultural transmission. The broader Sorbian cultural festival in Upper Lusatia, with participation from Bad Muskau groups, includes folk theater, song recitals, and craft stalls that highlight regional heritage, often held in spring or summer to coincide with seasonal rites.[65][66] Preservation initiatives are central to sustaining this heritage amid linguistic and demographic pressures. The Sorbian Cultural Centre in nearby Schleife operates as a museum and educational facility, displaying artifacts like Muskau-region chest costumes (Brusttracht), weaving tools, and exhibits on local customs, serving residents from Bad Muskau through workshops and guided tours. Language revitalization efforts include bilingual programs in area schools, where Upper Sorbian is taught alongside German to younger generations, supported by media such as the weekly newspaper Serbske Nowiny and Sorbian-language radio broadcasts from the regional Witaj foundation, which produce content on folklore and daily life.[67][68] Cross-border exchanges with Polish communities in Łęknica enhance these efforts, leveraging the shared Muskau Park as a venue for joint cultural programs like bilingual storytelling sessions and heritage walks that bridge Sorbian and Polish Slavic traditions, promoting mutual understanding and collaborative preservation projects. As part of Bad Muskau's ethnic composition, Sorbs represent a vital minority actively shaping the town's identity through these initiatives.[69]Notable people

Historical figures

Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785–1871) is the most influential historical figure in Bad Muskau's development, renowned as a prince, travel writer, and innovative landscape designer. Born on 30 October 1785 at Muskau Castle in the town, he was the eldest child of Count Ludwig Carl Hans Erdmann von Pückler and Countess Clementine of Callenberg, inheriting the Muskau estate upon his father's death in 1811.[70] Elevated to princely rank in 1822, Pückler transformed the surrounding landscape starting in 1815, creating Muskau Park as a pioneering English-style garden that harmoniously blended natural features with artificial elements like bridges and ruins.[71] His design work, which continued until financial difficulties forced him to sell the estate in 1845, established Bad Muskau as a center of 19th-century landscape architecture and earned the park UNESCO World Heritage status in 2004.[72] Beyond design, Pückler gained fame as a writer through works like Letters of a Dead Man (1830), a pseudonymous collection of letters recounting his 1826–1828 travels across England, Wales, Ireland, and Algeria. The book offered vivid social commentary and critiques of British society, achieving commercial success and influencing European travel literature.[73] His adventurous spirit and unconventional lifestyle, including multiple marriages and extensive explorations, further cemented his legacy as a cosmopolitan nobleman whose ideas on aesthetics and personal freedom resonated widely.[70] In Bad Muskau's medieval past, the area was governed by regional lords under Bohemian and later Saxon authority, with a fortress on the Neisse River first documented in the 13th century and the town mentioned in records from 1253 onward.[2] These early rulers laid the foundations for the castle complex that Pückler later expanded, though specific individuals from this era remain less documented compared to his transformative contributions.Modern residents

Bad Muskau has produced several professional ice hockey players who have competed in German leagues, contributing to the town's reputation in winter sports. Ralf Hantschke, born in 1965, played as a right wing in the Deutsche Eishockey Liga (DEL) for teams including the Kölner Haie and Eisbären Berlin, amassing over 400 career points in more than 500 games. Robert Francz, born in 1978, appeared in the DEL for clubs such as the Kassel Huskies and Grizzly Adams Wolfsburg, known for his defensive prowess during a career spanning the late 1990s to 2010s. More recent talents include Frank Hördler, born in 1985, a defenseman who has played for Eisbären Berlin in the DEL and represented Germany internationally, earning over 300 DEL appearances.[74] Toni Ritter, born in 1990, has been a forward in the DEL2 and DEL for teams like the Löwen Frankfurt, noted for his physical play style.[75] Women players from the town include Susann Götz, born in 1982, a defender who competed in the German women's national team and various leagues.[76] In local governance, Thomas Krahl has served as mayor since 2019, elected with a narrow 50.1% majority in a closely contested race against independent candidate Uwe Unger; his term focuses on tourism and community development in this border spa town. Krahl, a CDU member, oversees initiatives tied to the town's UNESCO-listed park while preparing for re-election in September 2026.[77] Cultural preservation efforts in Bad Muskau feature figures like Cord Panning, who has directed the Stiftung Fürst-Pückler-Park since 1997, leading restoration projects for the 19th-century landscape park, including UNESCO World Heritage maintenance and cross-border Polish-German collaboration; his contract was extended through 2029.[78] Among contemporary artists, Tibor Horvath, based in Bad Muskau, creates abstract paintings exploring color and form, with works exhibited internationally and rooted in the local Lusatian environment.[79]References

- https://de.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Bad_Muskau