Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

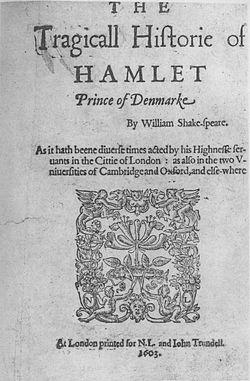

Bad quarto

View on Wikipedia

A bad quarto, in Shakespearean scholarship, is a quarto-sized printed edition of one of Shakespeare's plays that is considered to be unauthorised, and is theorised to have been pirated from a theatrical performance without permission by someone in the audience writing it down as it was spoken or, alternatively, written down later from memory by an actor or group of actors in the cast – the latter process has been termed "memorial reconstruction". Since the quarto derives from a performance, hence lacks a direct link to the author's original manuscript, the text would be expected to be bad, i.e. to contain corruptions, abridgements and paraphrasings.[1][2]

In contrast, a good quarto is considered to be a text that is authorised and which may have been printed from the author's manuscript (or a working draft thereof, known as his foul papers), or from a scribal copy or prompt copy derived from the manuscript or foul papers.[3]

The concept of the bad quarto originates in 1909, attributed to A W Pollard and W W Greg. The theory defines as "bad quartos" the first quarto printings of Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Hamlet,[2] and seeks to explain why there are substantial textual differences between those quartos and the 1623 printing of the first folio edition of the plays.

The concept has expanded to include quartos of plays by other Elizabethan authors, including Peele's The Battle of Alcazar, Greene's Orlando Furioso, and the collaborative script, Sir Thomas More.[4][5]

The theory has been accepted, studied and expanded by many scholars; but some modern scholars are challenging it[6][7][8][9] and those, such as Eric Sams,[10] consider the entire theory to be without foundation. Jonathan Bate states that "late twentieth- and early twenty-first century scholars have begun to question the whole edifice".[11]

Origins of bad quarto theory

[edit]The concept of the bad quarto as a category of text was created by bibliographer Alfred W. Pollard in his book Shakespeare Folios and Quartos (1909). The idea came to him in his reading of the address by the editors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, which appears at the beginning of Shakespeare's First Folio and is titled, "To the Great Variety of Readers". Heminges and Condell refer to "diuerse stolne, and surreptitious copies" of the plays. Up until 1909, it had been thought that the reference to stolen copies was a general reference to all quarto editions of the plays.

Pollard, however, claimed that Heminges and Condell meant to refer only to "bad" quartos (as defined by himself), and Pollard listed as bad the first quartos of Romeo and Juliet (1597), Henry V (1600), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), Hamlet (1603), and Pericles (1609). Pollard pointed out that not only do these five texts contain "badness" (namely significant textual errors and corruptions), but also that there is (legal) "badness" in those who pirated them.[12]

Scholar W. W. Greg worked closely with Pollard and published the bad quarto of The Merry Wives of Windsor,[13] which is a work that is significant in the history of the "bad quarto" theory. Greg described how the text may have been copied, and he identified the actor who played the role of "Host" as the culprit. Greg called the process that the actor may have used "memorial reconstruction", a phrase later used by other scholars[14][15] – meaning, literally, a reconstruction of it from memory.

For Shakespeare, the First Folio of 1623 is the crucial document; of the 36 plays contained in that collection, 18 have no other source. The other 18 plays had been printed in quarto form at least once between 1594 and 1623, but since the prefatory matter in the First Folio itself warns against earlier texts, which are termed "stol'n and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by frauds and stealths of injurious impostors", 18th- and 19th-century editors of Shakespeare tended to ignore the quarto texts and preferred the Folio.

It was at first suspected that the bad quarto texts represented shorthand reporting, a practice mentioned by Thomas Heywood in the Prologue to his 1605 play If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody; reporters would surreptitiously take down a play's text in shorthand during a performance and pirate a popular play for a competing interest. However, Greg and R.C.Rhodes argued instead for an alternative theory: since some of the minor speeches varied less (from the folio text) than those of major characters, their hypothesis was that the actors who played the minor roles had reconstructed the play texts from memory and thereby gave an accurate report of the parts that they themselves had memorized and played, but a less correct report of the other actors' parts.

The idea caught on among Shakespearean scholars. Peter Alexander added The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster (1594) and The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York (1595) – the earliest versions of Henry VI, Part 2 and Henry VI, Part 3 – to the roster of bad quartos; both had been previously thought to be source plays for Shakespeare's later versions of the same histories. The concept of the bad quarto was then extended to play texts by authors other than Shakespeare, and by the second half of the 20th century the idea was being widely adopted.[16] However, by the end of the century dissenting views had been published, such as the work of Laurie Maguire, then at the University of Ottawa.

Criticism and alternative hypotheses

[edit]Various problems exist with the bad quarto hypothesis, particularly concerning the notion of memorial reconstruction. Furthermore, the hypothesis makes no allowance for changes to occur in the text across the enormous period between 1594 and 1623 (almost thirty years), from revisions by the author, abridgements for special circumstances, or natural evolution resulting from improvements to the text made by the actors in performance.

For some plays, critics seem undecided even as to what amounts to a bad quarto. The first quarto of Richard III, for instance, is often now termed a bad quarto, "even though it is an unusually good bad quarto".[17] Alexander himself recognised that the idea of memorial reconstruction did not apply perfectly to the two plays he studied, which possessed problematical features that could not be explained, and in the end retreated to arguing, instead, that the quartos of the two early histories were "partial" memorial reconstructions.

Some critics, including Eric Sams and Hardin Craig, dispute the entire concept of memorial reconstruction by pointing out that, unlike shorthand reporting, no reliable historical evidence exists that actors reconstructed plays from memory. They believe that memorial reconstruction is a modern fiction.

Individual scholars have sometimes preferred alternative explanations for variant texts, such as revision or abridgement by the author. Steven Urkowitz argued the hypothesis that King Lear is a revised work, in Shakespeare's Revision of "King Lear". Some scholars have argued that the more challenging plays of the Shakespearean canon, such as All's Well That Ends Well and Troilus and Cressida, make sense as works that Shakespeare wrote in the earliest, rawest stage of his career and later revised with more sophisticated additions.

Steven Roy Miller considers a revision hypothesis, in preference to a bad-quarto hypothesis, for The Taming of a Shrew, the alternative version of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew.[18]

Robert Burkhart's 1975 study Shakespeare's Bad Quartos: Deliberate Abridgements Designed for Performance by a Reduced Cast provides another alternative to the hypothesis of bad quartos as memorial reconstruction. Other studies have also questioned the "orthodox view" on bad quartos, as in David Farley-Hills's work on Romeo and Juliet.

Maguire study

[edit]In 1996, Laurie Maguire of the Department of English at the University of Ottawa published a study[19] of the concept of memorial reconstruction, based on the analysis of errors made by actors taking part in the BBC TV Shakespeare series, broadcast in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

She found that actors typically add, drop or invert single words. But the larger-scale errors that would be expected if actors were attempting to piece together the plays some time after their performance failed to appear in all but a few of the bad quartos. The study uncovered only limited circumstantial evidence suggestive of possible memorial reconstruction, in the bad quartos of Hamlet, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Pericles.

In fact, according to Maguire, virtually all the so-called bad quartos appear to be accurate renditions of original texts, which "merit our attention as valid texts in their own right".[20] This challenges the entire concept of bad quartos as pirated editions, mired in textual corruption; and presents them, rather, as earlier versions of the plays printed in the 1623 folio.

Of other playwrights

[edit]Though the bad quarto concept originated in reference to Shakespearean texts, scholars have also applied it to non-Shakespearean play texts of the English Renaissance era.

In 1938, Leo Kirschbaum published "A Census of Bad Quartos" and included 20 play texts.[21] Maguire's 1996 study examined 41 Shakespearean and non-Shakespearean editions that have been categorised as bad quartos, including the first editions of Arden of Feversham, The Merry Devil of Edmonton and Fair Em, plays of the Shakespeare Apocrypha; plus George Chapman's The Blind Beggar of Alexandria; Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus and The Massacre at Paris; Part 1 of Heywood's If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody; and Beaumont and Fletcher's The Maid's Tragedy.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Jenkins, Harold. "Introduction". Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Arden Shakespeare (1982) ISBN 1-903436-67-2. p. 19.

- ^ a b Duthie, George Ian. "Introduction; the good and bad quartos". The Bad Quarto of Hamlet. CUP Archive (1941). pp. 1-4

- ^ Duthie, George Ian. "Introduction; the good and bad quartos". The Bad Quarto of Hamlet. CUP Archive (1941). pp. 5-9

- ^ Erne, Lukas. Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist. Cambridge University Press. (2013) ISBN 9781107029651 p. 223

- ^ Maguire, Laurie E. Shakespearean Suspect Texts: The 'Bad' Quartos and Their Contexts. Cambridge University Press (1996), ISBN 9780521473644, p. 79

- ^ Irace, Kathleen. Reforming the "bad" Quartos: Performance and Provenance of Six Shakespearean First Editions. University of Delaware Press (1994) ISBN 9780874134711 p.14.

- ^ Richmond, Hugh Macrae. Shakespeare's Theatre: A Dictionary of His Stage Context. Continuum (2002) ISBN 0 8264 77763. p.58

- ^ Jolly, Margrethe. The First Two Quartos of Hamlet: A New View of the Origins and Relationship of the Texts. McFarland (2014) ISBN 9780786478873

- ^ McDonald, Russ. The Bedford Companion to Shakespeare: An Introduction with Documents. Macmillan (2001) ISBN 9780312248802 p.203

- ^ Sams, Eric. The Real Shakespeare; Retrieving the Early Years, 1564 — 1594. Meridian (1995) ISBN 0-300-07282-1

- ^ Bate, Jonathan. "The Case for the Folio". (2007) Playshakespeare.com

- ^ De Grazia, Margreta. "The essential Shakespeare and the material book." Orgel, Stephe and others, editors. Shakespeare and the Literary Tradition. Courier Corporation (1999) ISBN 9780815329671, p. 51.

- ^ Greg, W. W. editor. Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor, 1602. Oxford; At the Clarendon Press (1910)

- ^ Pollard, Alfred W. Shakespeare folios and quartos: a study in the bibliography of Shakespeare's plays, 1594–1685. University of Michigan Library (1909)

- ^ Erne, Lukas. Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist. Cambridge University Press (2013) ISBN 9781107029651. p. 221

- ^ Halliday, Shakespeare Companion, p. 49.

- ^ Evans, Riverside Shakespeare, p.754.

- ^ Miller, pp.6–33.

- ^ Maguire, L. Shakespeare's Suspect Texts: the 'Bad' Quartos and their context Cambridge Univ Press (1996)

- ^ Quoted in The Sunday Telegraph, 17 March 1996, p. 12

- ^ Maguire, pp. 85–6.

- ^ Maguire, pp. 227–321.

Sources

[edit]- Alexander, Peter. Shakespeare's Henry VI and Richard III. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1929.

- Burkhart, Robert E. Shakespeare's Bad Quartos: Deliberate Abridgements Designed for Performance by a Reduced Cast. The Hague, Mouton, 1975.

- Craig, Hardin. A New Look at Shakespeare's Quartos. Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 1961.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, textual editor. The Riverside Shakespeare. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1974.

- Farley-Hills, David. "The 'Bad' Quarto of Romeo and Juliet," Shakespeare Survey 49 (1996), pp. 27–44.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964.

- Hart, Alfred, "Stolne and Surreptitious Copies: A Comparative Study of Shakespeare's Bad Quartos," Melbourne Univ. Press, 1942 (reprinted Folcroft Library Editions, 1970).

- Kirschbaum, Leo. "A Census of Bad Quartos." Review of English Studies 14:53 (January 1938), pp. 20–43.

- Maguire, Laurie E. Shakespearean Suspect Texts: The "Bad" Quartos and Their Contexts. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Miller, Steven Roy, ed. The Taming of a Shrew: the 1594 Quarto. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Pollard, Alfred W. Shakespeare Folios and Quartos. London, Methuen, 1909.

- Rhodes, R. C. Shakespeare's First Folio. Oxford, Blackwell, 1923.

- Urkowitz, Steven. Shakespeare's Revision of "King Lear." Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1980.