Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

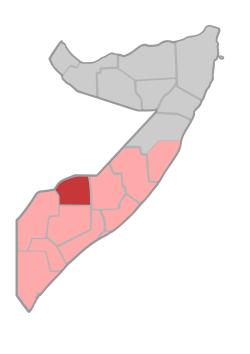

Bakool

View on WikipediaBakool (Somali: Bakool, Maay: Bokool, Arabic: بكول) is a region (gobol) in southwestern Somalia.[4]

Key Information

Overview

[edit]It is bordered by the Somali regions of Hiiraan, Bay and Gedo.

Bakool, like Gedo, Bay and most parts of the Jubbada Dhexe (Middle Juba) region, used to be a part of the old Upper Region, which was subdivided in the mid-1980s. The town of Hudur is the administrative capital of the region.

In March 2014, Somali Armed Forces assisted by an Ethiopian battalion with AMISOM re-captured the Bakool province's capital Hudur from the Al-Shabaab militant group.[5] The offensive was part of an intensified military operation by the allied forces to remove the insurgent group from the remaining areas in southern Somalia under its control.[6]

Districts

[edit]Major towns

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources list Rabdhure, others Yed

References

[edit]- ^ "Somalia: Subdivision and cities". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ "ISO 3166 — Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions". International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "Somalia". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Somalia: Federal Govt, Ethiopian forces liberate strategic town of Hudur". Garowe Online. 7 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Somalia: Federal Govt, AMISOM troops clash with Al Shabaab". Garowe Online. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Regions, districts, and their populations: Somalia 2005 (Draft)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-28.