Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Grand Prix of Baltimore

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| IndyCar Series | |

|---|---|

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland, USA 39°17′N 76°37′W / 39.283°N 76.617°W |

| Corporate sponsor | Street and Racing Technology |

| First race | 2011 |

| Last race | 2013 |

| Circuit information | |

| Surface | Asphalt/Concrete |

| Length | 2.04 mi (3.28 km) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Lap record | 1:19.0055 ( |

The Grand Prix of Baltimore presented by SRT was an IndyCar Series and American Le Mans Series race for 3 years held on a street circuit in Baltimore, Maryland. The inaugural race was held September 4, 2011.[1] ESPN said it was the best inaugural street race in North America in the last 30 years.[2] The races were contested on a temporary street circuit around the Inner Harbor area of downtown Baltimore.[3]

Baltimore Racing Development signed a multi-year contract with IndyCar and the City of Baltimore to organize the race, but the city terminated their contract with BRD at the end of 2011 due to unpaid debts.[4] On February 15, 2012, it was announced that the city of Baltimore had entered into a five-year agreement with Downforce Racing to manage the race.[5] However, Downforce failed to fulfill their obligations to the city. On May 10, 2012, it was announced that Race On LLC. and Andretti Sports Marketing, led by racing legend Michael Andretti would take over the organization and promotion of the event.[6] Race On LLC is owned by Gregory O'Neill and J.P. Grant III. On September 13, 2013, it was announced that the race would not be held in 2014 or 2015 due to scheduling conflicts.[7]

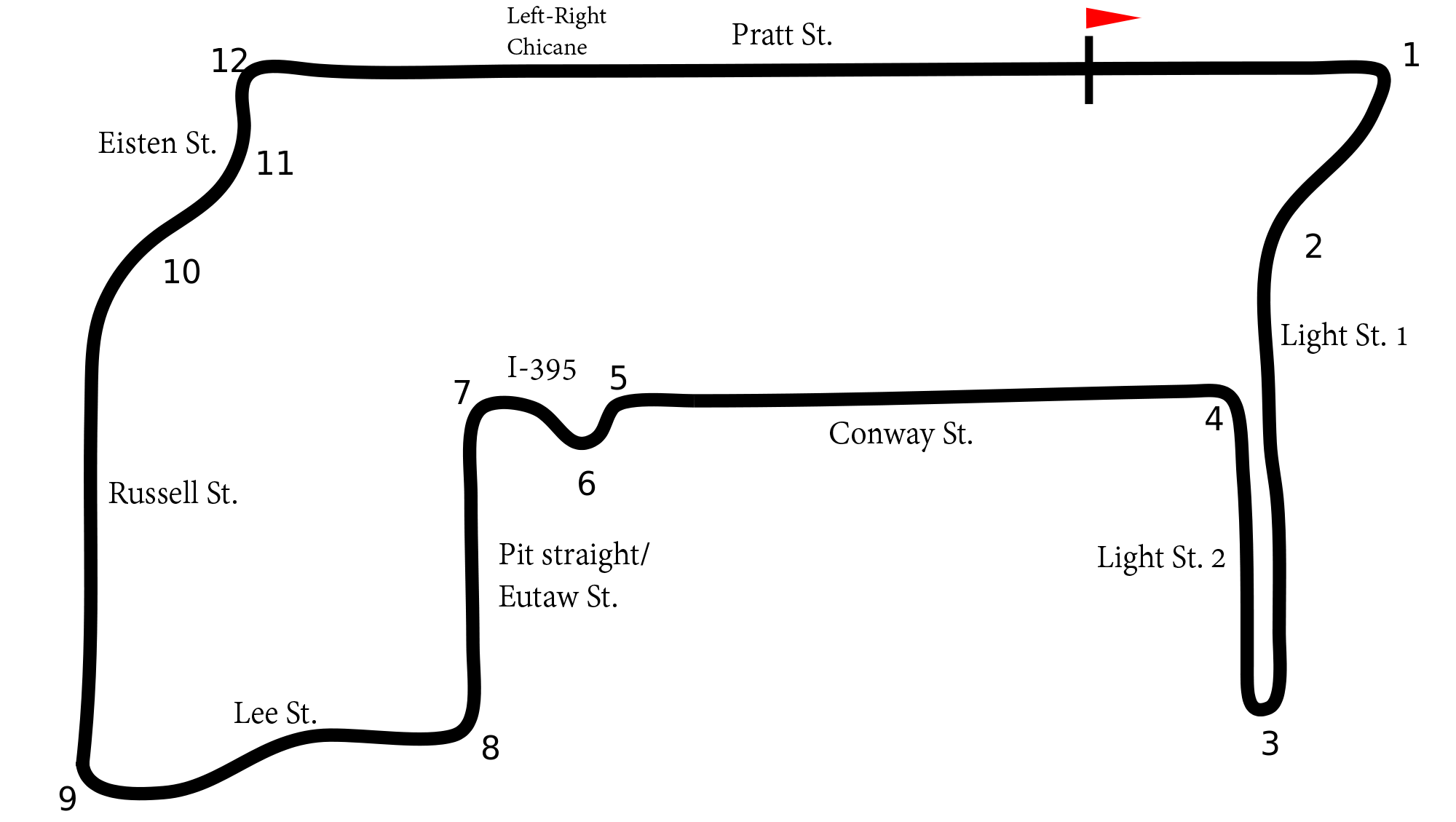

Circuit

[edit]The circuit is a 2.04-mile (3.28 km) temporary street circuit that is run in a clockwise direction, with the start-finish line located on Pratt Street, passing by various Baltimore landmarks, including the Baltimore Convention Center, the Inner Harbor, and Camden Yards.[8] The cars travel east along Pratt Street to Light Street, where they turn right and travel south along the northbound lanes to the intersection between Light and Lee Streets. This forms the slowest corner on the circuit, a right-hand hairpin turn that leads the cars back north along Light Street's southbound lanes to Conway Street. The cars turn left here and head west along Conway Street to the Camden Station. They then navigate a chicane designed to slow the cars down before the pit entry — the circuit is unusual in that the pits are not located on the main straight — and turn left again. The cars circle around Oriole Park at Camden Yards stadium to Russell Street, where they turn north once more. This short straight feeds into a pair of sweepers, right and then left, that lead to Pratt Street and the 0.5-mile (0.80 km) long main straight. Finally, the cars navigate a temporary chicane placed at the junction between Pratt and Howard Street as they cross train lines.[9]

Following the 2011 race, several drivers offered the opinion that the temporary chicane on the main straight was unnecessary, and it was subsequently removed ahead of the 2012 race so as to increase entry speeds into the first corner. However, during the first practice sessions for the 2012 race, several drivers — including Simon Pagenaud and Oriol Servià — became airborne as they crossed the train tracks. IndyCar officials abandoned the practice session and reinstalled the temporary chicane.[10]

Other changes for the 2012 race included the re-profiling of the chicane before the pit entry. In 2011, the circuit had been narrowed down to a single lane with several tight corners to force the cars to slow down. This was simplified for 2012 and widened, slowing the cars down, but preventing the field from being forced through a bottleneck.[citation needed]

Past winners

[edit]

IndyCar Series

[edit]| Season | Date | Driver | Team | Chassis | Engine | Race Distance | Race Time | Average Speed (mph) |

Report | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laps | Miles (km) | |||||||||

| 2011 | September 4 | Penske Racing | Dallara | Honda | 75 | 153 (246.23) | 2:02:19 | 75.046 | Report | |

| 2012 | September 2 | Andretti Autosport | Dallara | Chevrolet | 75 | 153 (246.23) | 2:09:03 | 71.136 | Report | |

| 2013 | September 1 | Schmidt Motorsports | Dallara | Honda | 75 | 153 (246.23) | 2:16:32 | 67.234 | Report | |

American Le Mans Series

[edit]| Season | LMP1 Winning Team | LMP2 Winning Team | LMPC Winning Team | GT Winning Team | GTC Winning Team | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMP1 Winning Drivers | LMP2 Winning Drivers | LMPC Winning Drivers | GT Winning Drivers | GTC Winning Drivers | ||

| 2011 | Did not participate | Results | ||||

| 2012 | Results | |||||

| 2013 | Report | |||||

Support races

[edit]

|

|

|

Lap records

[edit]The unofficial all-time outright track record set during a race weekend is 1:17.5921, set by Will Power in a Dallara DW12 during qualifying for the 2012 Grand Prix of Baltimore.[11] The fastest official race lap records at the Grand Prix of Baltimore are listed as:

| Category | Time | Driver | Vehicle | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Prix Circuit: 3.280 km (2011–2013) | ||||

| IndyCar | 1:19.0055 | Will Power | Dallara DW12 | 2012 Grand Prix of Baltimore |

| Indy Lights | 1:23.9799[12] | Sebastián Saavedra | Dallara IPS | 2012 Baltimore Indy Lights round |

| LMP1 | 1:24.982[13] | Lucas Luhr | HPD ARX-03a | 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge |

| LMP2 | 1:27.641[13] | Christophe Bouchut | HPD ARX-03b | 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge |

| Star Mazda | 1:28.860[14] | Sage Karam | Star Formula Mazda 'Pro' | 2012 Baltimore Star Mazda Championship round |

| LMPC | 1:29.026[13] | Bruno Junqueira | Oreca FLM09 | 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge |

| GT2 | 1:30.313[13] | Oliver Gavin | Chevrolet Corvette C6 ZR1 | 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge |

| US F2000 | 1:31.645[15] | Matthew Brabham | Van Diemen DP08 | 2012 Baltimore USF2000 round |

| GTC | 1:35.312[13] | Damien Faulkner | Porsche 911 (997) GT3 Cup | 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge |

Controversy

[edit]Along with the closing of the commercial center of downtown Baltimore for track preparation, trees were removed from city streets, spawning a court case.[16] Also, Baltimore Brew identified $42,400 in campaign contributions over the preceding four years to Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and other political officials from investors and businesses that stood to gain from the race being held.[17]

After its inaugural run, it was reported that the race failed to bring as much economic activity to Baltimore as had been promised[18] and that Baltimore Racing Development has had difficulties paying monies owed to local businesses[19] and the state, the latter resulting in a $567,000 tax lien being filed.[20] With Baltimore Racing Development $3 million in debt, including nearly $1.2 million owed to Baltimore City, the city terminated their contract with BRD at the end of 2011. This meant the race would only take place again if both the city and IndyCar approved a new organizer. IndyCar officials have expressed hope that a new organizer will be found.[4] The city of Baltimore announced on February 10, 2012, that a five-year deal with race organizer Downforce Racing, LLC was being finalized and would be presented to the city Board of Estimates February 22.[21] The new contract includes provisions such as a $3 per ticket surcharge for city services to reduce the risk of unpaid fees to the city.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Lewandowski, Dave (June 2, 2010). "Series roars into Baltimore in 2011". IndyCar.com. Indy Racing League. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Oreovicz, John (September 5, 2011). "Baltimore embraces inaugural grand prix". ESPN. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Baltimore Grand Prix Set For August 2011". WBAL-TV. June 2, 2010. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ a b McCorkell, Meghan (December 30, 2011). "City Of Baltimore Terminates Contract With Grand Prix Organizers". CBS Baltimore. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Scharper, Julie (February 15, 2012). "Baltimore to unveil new Grand Prix contract". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 15, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Andretti to lead new Baltimore Grand Prix team". Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Dance, Scott (September 13, 2013). "Grand Prix of Baltimore canceled through 2015, and likely beyond". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on August 2, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Scharper, Julie (June 2, 2010). "Baltimore Grand Prix hailed as 'game-changer' for city". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ {Dave Lewandowski | Published: Jul 30, 2012| title=Baltimore Grand Prix surprises veterans and first-timers | url=https://www.autoweek.com/racing/indycar/a1988451/baltimore-grand-prix-surprises-veterans-and-first-timers/}

- ^ Pruett, Marshall (August 31, 2012). "INDYCAR: Airborne Cars Halt Opening Baltimore Practice". SPEED TV. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ "Baltimore". Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "2012 Baltimore Indy Lights". Motor Sport Magazine. September 2, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Baltimore 2 Hours 2012". September 2, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "2012 Indy Pro 2000 Baltimore (Race 2)". September 2, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ "2012 USF2000 Baltimore Grand Prix Presented by Allied Building Products - Cooper Tires USF2000 Championship powered by Mazda - Final Race Report - Round 12" (PDF). September 2, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Schaffer, Christian. "Tree removal plan for Baltimore Grand Prix criticized". WMAR television. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Shen, Fern (August 25, 2011). "Grand Prix boosters race ahead with campaign contributions". Baltimore Brew.

- ^ Brumfield, Sarah. "AP Exclusive: Grand Prix short of projections". Bloomberg Business Week. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Furchgott, Roy (November 15, 2011). "Amid New Lawsuits, Prospects Weaken for 2012 Baltimore Grand Prix". The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Jackson, Alexander (November 21, 2011). "Baltimore Grand Prix organizers hit with $600,000 tax lien". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Rawlings-Blake To Announce New Deal On Baltimore Grand Prix CBS Baltimore

External links

[edit]Grand Prix of Baltimore

View on GrokipediaHistory

Inception and Development

The Baltimore Grand Prix originated from efforts by Baltimore Racing Development (BRD), which formally announced on June 2, 2010, plans for an annual motorsport event featuring the IZOD IndyCar Series starting in 2011.[10] The initiative aimed to revitalize downtown Baltimore by transforming underutilized urban spaces into a high-profile racing venue, drawing parallels to successful street circuits in cities like Long Beach and Toronto to boost local tourism and economic activity.[11] BRD selected a 2.2-mile street circuit around the Inner Harbor, incorporating landmarks such as Oriole Park at Camden Yards and the waterfront promenade, to create a visually striking layout with 12 turns, including a signature hairpin at Pratt Street.[12] This location was chosen for its potential to showcase Baltimore's architecture and harbor views to national audiences, while minimizing permanent infrastructure needs through temporary barriers and grandstands. The city approved the plan in May 2010, committing to construct approximately 50,000 seats and provide logistical support, including traffic management and event subsidies estimated in the millions to cover setup costs.[13] Partnerships were secured with the IndyCar Series for the headline race and the American Le Mans Series for sports car events, enabling a multi-tiered weekend program to attract diverse spectators. Initial economic projections forecasted an annual impact of around $70 million from visitor spending on hotels, dining, and entertainment, based on anticipated attendance exceeding 100,000 and ancillary activities like fan zones.[14] These estimates, prepared by event consultants, emphasized direct infusions from out-of-town attendees to stimulate local businesses during the Labor Day weekend slot.[15]Inaugural Race (2011)

The inaugural Grand Prix of Baltimore took place over the weekend of September 2–4, 2011, marking the debut of a temporary street circuit in the city's Inner Harbor area for the IZOD IndyCar Series and American Le Mans Series (ALMS). Setup challenges emerged early, with road closures causing severe traffic congestion for commuters as preparations began days in advance, and repairs to the track surface extending into Thursday night just before initial sessions.[16][17][18] Race promoter Baltimore Racing Development (BRD) attributed a delay in Friday's practice and qualifying to unresolved preparation matters, including barriers and infrastructure, forcing drivers and spectators to adapt amid the disruptions.[19] Saturday's ALMS Baltimore Grand Prix Sports Car Challenge saw the #20 Oryx Dyson Racing Lola B09/60, driven by Steven Kane and Humaid Al Masaood, claim overall victory after a competitive 2-hour, 45-minute contest shortened by time constraints rather than incidents.[20] The event highlighted the circuit's demanding layout, with GT class action featuring strong finishes from BMW Team RLL entries.[21] The headline IndyCar race on Sunday, September 4, unfolded over 75 laps of the 2.04-mile, 12-turn course, where Australian driver Will Power delivered a dominant performance in the #12 Verizon Penske Dallara to secure the win, narrowing points leader Dario Franchitti's championship advantage to five with three races remaining.[22] Despite the earlier hurdles, organizers reported weekend attendance nearing 150,000, exceeding initial expectations of 100,000 and drawing praise from veterans for crowd size rivaling major events outside the Indianapolis 500.[23] Media accounts emphasized the spectacle's energy and urban appeal, though setup delays signaled early organizational strains by BRD that foreshadowed future promoter transitions.[18][24]Events of 2012 and 2013

The 2012 Grand Prix of Baltimore, held from August 31 to September 2, incorporated circuit alterations based on driver input from the prior year, including removal of the chicane on the Pratt Street straightaway to promote higher speeds and overtaking opportunities, widening of the right-hand Turn 1 for improved entry, and reshaping of Turns 5 and 6 near the pit entrance to mitigate bumps and enhance flow.[25][26] These modifications, implemented by organizers under Race On LLC, aimed to refine racing dynamics and operational efficiency following the inaugural event's logistical hurdles. The IndyCar Series race concluded with Ryan Hunter-Reay of Andretti Autosport victorious after 75 laps, finishing 1.4 seconds ahead of Ryan Briscoe.[27] Attendance reached an estimated 131,000, down approximately 30 percent from 2011 but viewed as a operational success by event managers due to streamlined timing and reduced disruptions.[28][29] For the 2013 edition on September 1, refinements carried forward from 2012's track adjustments contributed to a more stable layout, though the event remained challenged by urban infrastructure constraints. The IndyCar race, marked by multiple incidents including crashes that red-flagged proceedings, was won by Simon Pagenaud of Schmidt Hamilton HP Motorsports. Attendance climbed to 152,000, up from the previous year, reflecting sustained fan engagement evidenced by increased ticket sales and sponsorship commitments amid efforts to secure a title partner. Organizers reported bullish prospects for revenue streams, with the event stabilizing financially through these gains despite underlying fiscal pressures not publicly detailed at the time. The American Le Mans Series portion featured a win by Miguel Barbosa in the P2 class, underscoring the multi-series format's appeal.[30][31][32]Cancellation and Legacy

On September 13, 2013, organizers announced the cancellation of the Grand Prix of Baltimore for 2014 and 2015, citing scheduling conflicts with the IndyCar Series calendar as the immediate barrier to continuation.[7][33] Underlying these conflicts were chronic financial instabilities, including the promoter's insolvency and the City of Baltimore's refusal to renew its contract after accumulating unpaid obligations.[34] By late 2011, Baltimore Racing Development, the event's primary organizer, reported debts exceeding $12 million against less than $100,000 in cash reserves, encompassing liabilities to vendors, the city for services and taxes totaling over $1.1 million, and infrastructure costs.[35][36] These fiscal shortfalls persisted into 2013, rendering the event untenable without external bailouts that never materialized. As of October 2025, no substantive revival efforts have emerged, with the race absent from IndyCar schedules since 2013 and no documented proposals from promoters or city officials to reinstate it. Retrospectives attribute this stagnation to unresolved debts and operational overextensions, which eroded stakeholder confidence despite initial projections of $65–70 million in annual economic benefits that failed to offset net losses.[9] The Grand Prix's legacy endures as a cautionary case in urban motorsport ventures, demonstrating how high setup costs—including street modifications and logistics—can outpace revenue from ticket sales and tourism in non-permanent circuits. While the event briefly energized local interest and showcased Baltimore's waterfront, empirical outcomes of promoter bankruptcy filings and vendor disputes underscored unsustainable economics, prompting greater scrutiny in subsequent city-backed races elsewhere.[8] This fiscal realism has deterred analogous high-risk street events, favoring established venues with proven profitability over speculative urban experiments.[37]Circuit

Design and Layout

The Grand Prix of Baltimore utilized a 12-turn, approximately 2-mile temporary street circuit routed through downtown Baltimore's urban core. The layout featured a blend of high-speed straights and technical corners, with Pratt Street serving as a primary straightaway capable of supporting speeds exceeding 170 mph, facilitating aggressive passing maneuvers. Tight sections, including a prominent right-hand hairpin adjacent to Oriole Park at Camden Yards, demanded precise braking and acceleration, contributing to the circuit's reputation for dynamic racing.[25][38] Engineering choices prioritized overtaking opportunities within the constraints of city streets, incorporating temporary barriers to channel vehicles safely amid fixed infrastructure like buildings and harborfront promenades. Prior to the 2012 event, track modifications removed a chicane from the frontstretch to widen the racing line and reduce bottlenecks, enhancing flow and competition as requested by drivers. The configuration integrated landmarks such as the Inner Harbor, providing spectators with views of maritime scenery alongside the action, while fan zones leveraged adjacent public spaces for accessibility.[25][39] In comparison to established street circuits like Long Beach, Baltimore's design emphasized deeper immersion into a major city's commercial and cultural heart, looping around sports venues and waterfront districts rather than peripheral roads, which amplified the event's spectacle but heightened logistical challenges from urban density. This setup distinguished it as one of the few contemporary North American street races centered in a dense metropolitan area.[11]Construction and Operational Logistics

The setup for the Grand Prix of Baltimore required extensive multi-week preparations, including the installation of concrete barriers, safety fencing, and temporary grandstands along the street circuit.[40][41] In 2012, crews began heavy-duty work on barriers and related infrastructure in late August, with road closures such as portions of Pratt Street implemented specifically for wall construction starting in early August.[42][43] Pre-event planning estimated that erecting grandstands and barriers would take approximately one month prior to the race weekend, followed by two weeks for teardown and removal of traffic barriers after the event.[44][45] Operational logistics involved close coordination with Baltimore city agencies and state authorities to manage traffic disruptions in the dense urban environment. The Maryland State Highway Administration (SHA) and Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA) implemented detours and additional emergency traffic patrols along key routes like I-95 and I-395 to maintain flow and respond to incidents during race weekends.[46][47] Specialized traffic control firms handled road closures, detours, and race-day operations to minimize citywide impacts, ensuring local access where possible while directing spectator and freight traffic.[48] Event organizers developed contingency plans with public safety agencies to sustain daily urban functions amid the temporary infrastructure.[11] Adaptations for urban challenges included noise mitigation measures informed by pre-event analyses projecting race car sound levels up to 118 decibels at certain track points, exceeding typical speech interference thresholds.[49][50] Residents near the circuit were advised to use earplugs or earmuffs for protection during high-noise periods.[51] Setup efficiency saw incremental refinements across years; for instance, 2012 preparations incorporated circuit modifications like chicane adjustments directly into the build process, drawing on inaugural event experience to streamline barrier and fencing installations.[25] Emergency services integration featured on-site response teams and GIS-supported mapping for real-time coordination among organizers and officials.[52][46]Competition and Results

IndyCar Series Participation

The IndyCar Series served as the headline attraction for the Grand Prix of Baltimore from 2011 to 2013, with each event contested over 75 laps on the 2.04-mile (3.28 km), 12-turn temporary street circuit weaving through downtown landmarks including the Inner Harbor and Camden Yards.[12][5] These open-wheel races integrated into the IZOD IndyCar Series championship calendar as mid-to-late season fixtures, typically scheduled around Labor Day weekend to capitalize on East Coast accessibility and urban spectacle.[53] The format emphasized endurance and strategy on a layout blending long straights for overtaking with narrow, technical corners, where IndyCar's 550-horsepower V6 engines enabled trap speeds exceeding 190 mph on sections like Key Highway, testing chassis balance and tire management beyond conventional street circuit constraints.[54] Championship stakes heightened competitiveness, particularly in 2012's penultimate round, where the points leader entered with a 36-point margin over the runner-up, fostering aggressive on-track battles amid the circuit's unforgiving concrete barriers and elevation changes.[9] In 2011, as the series' 16th event of 17, the race similarly amplified title contention, with top performers gaining critical ground in a tight standings fight.[55] Drivers praised the track's emphasis on skill, citing its hairpin turn and rhythm sections as favoring precise handling and braking over raw acceleration, though some highlighted flaws like bumpy surfaces and limited runoff areas that amplified error penalties.[56][23] The inaugural 2011 layout drew mixed initial feedback for its novelty, with veterans noting exciting passing zones but critiquing the first corner's congestion risks.[31] Television coverage aired on NBC Sports Network (formerly Versus), attracting 591,000 average viewers for the 2011 debut—below promoter expectations but establishing a baseline for the event.[57] By 2013, viewership surged 54% over 2012, reflecting improved production and on-track drama despite the series' niche audience.[58]American Le Mans Series Events

The American Le Mans Series (ALMS) contested endurance-style races on the Baltimore street circuit annually from 2011 to 2013, integrating prototype and GT class competition alongside the headline IndyCar events to showcase a broader spectrum of sports car racing. These events featured multi-class grids where P1 prototypes—larger, diesel-powered machines emphasizing outright performance—and P2 prototypes, smaller gasoline or hybrid entries focused on agility, competed against GT cars derived from production models, all starting together under rolling starts adapted to the urban environment's safety protocols. The circuit's 2.4-mile layout, with its 90-degree corners and elevation changes around Inner Harbor landmarks, demanded chassis setups prioritizing mechanical grip and traction over high-speed stability, differing from permanent road courses and influencing tire management strategies for the roughly two-hour race durations.[59] In 2011, the inaugural ALMS Baltimore Grand Prix on September 3 covered 71 laps, with Dunlop-shod prototypes dominating the LMP1 class podium: the No. 20 Oryx Dyson Racing Lola B09/60-Mazda of Chris Dyson and Guy Smith securing victory ahead of the sister No. 16 Dyson entry. P2 and GT classes highlighted close racing amid the street track's abrasive surface, which accelerated tire wear and necessitated frequent strategy adjustments in the confined pit areas. The 2012 Baltimore Sports Car Challenge saw P2 prototypes lead due to mechanical issues sidelining all P1 entries, with the No. 055 Core Autosport HPD ARX-03c of Tom Kimber-Smith and Claude Bouchut winning overall after 67 laps, underscoring the class's reliability edge on the bumpy layout. GT competition remained intense, with manufacturers like Corvette and Porsche vying for positions in the production-derived category.[60][61] The 2013 event, held on August 31-September 1, featured a chaotic start with multi-car incidents but concluded with Muscle Milk Pickett Racing's No. 6 HPD ARX-06c of Klaus Graf and Lucas Luhr clinching P1 honors, while Corvettes achieved a 1-2 finish in GT led by the No. 4 of Jan Magnussen and Antonio Garcia. Pit strategies emphasized quick stops in the series' shared lane, constrained by the circuit's one-way streets and proximity to barriers, which heightened risks of contact during class-specific battles. Overall, ALMS participation diversified spectator appeal by contrasting the uniformity of IndyCar open-wheelers with the visceral sounds and designs of enclosed prototypes and GT machinery, drawing enthusiasts interested in endurance tactics over sprint-style qualifying prowess.[62][63][64]Support Races

The Grand Prix of Baltimore featured support races from the Mazda Road to Indy developmental ladder, which included the Cooper Tires USF2000 Championship Powered by Mazda, Star Mazda Championship, and Indy Lights series. These events showcased emerging drivers on the 2.04-mile street circuit, offering competitive racing for teenagers and young professionals aiming for advancement to higher levels of open-wheel competition.[23][65][66] In 2011, the weekend schedule integrated these series with practices on Friday, August 31, and races on Saturday, September 3, such as USF2000 Race #2 at 10:25 a.m., Star Mazda Race at 11:05 a.m., and Indy Lights Race at 12:15 p.m., culminating before the main events. Similar programming occurred in 2012, with USF2000 and Star Mazda races on Saturday, August 31, including a 28-car USF2000 field and joint autograph sessions for drivers from those series in the INDYCAR Fan Village. The 2013 edition maintained this structure, emphasizing youth-oriented competition that complemented the primary IndyCar and American Le Mans Series races without competing for spotlight.[67][68][66] These support races contributed to a multifaceted weekend program by highlighting accessible, high-speed action on the urban layout, including tight corners like the "Baltimore Horseshoe" and elevation changes that tested novice skills. Drivers in Star Mazda and USF2000, often in their mid-teens, demonstrated raw talent in open-wheel cars with Mazda engines, fostering a pipeline to professional series while engaging spectators with frequent on-track activity. Autograph opportunities and fan village interactions further integrated these events into the overall festival, drawing interest from families and motorsport enthusiasts beyond the headline races.[69][70]Past Winners and Lap Records

The IndyCar Series races at the Grand Prix of Baltimore produced the following winners over its three editions.[71][72][5]| Year | Date | Winner | Team | Chassis-Engine | Laps | Race Time/Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | September 4 | Will Power | Team Penske | Dallara IR03-Honda | 75 | 2:01:03.170 (151.8 mi) |

| 2012 | September 2 | Ryan Hunter-Reay | Andretti Autosport | Dallara DW12-Chevrolet | 75 | 1:55:36.7816 (151.8 mi) |

| 2013 | September 1 | Simon Pagenaud | Schmidt Hamilton Motorsports | Dallara DW12-Honda | 45 | 1:24:53.3506 (91 mi; shortened by incidents) |