Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gasoline

View on Wikipedia

Gasoline (North American English) or petrol (Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When formulated as a fuel for engines, gasoline is chemically composed of organic compounds derived from the fractional distillation of petroleum and later chemically enhanced with gasoline additives. It is a high-volume profitable product produced in crude oil refineries.[1]

The ability of a particular gasoline blend to resist premature ignition (which causes knocking and reduces efficiency in reciprocating engines) is measured by its octane rating. Tetraethyl lead was once widely used to increase the octane rating but is not used in modern automotive gasoline due to the health hazard. Aviation, off-road motor vehicles, and racing car engines still use leaded gasolines.[2][3] Other substances are frequently added to gasoline to improve chemical stability and performance characteristics, control corrosion, and provide fuel system cleaning. Gasoline may contain oxygen-containing chemicals such as ethanol, MTBE, or ETBE to improve combustion.

History and etymology

[edit]English dictionaries show that the term gasoline originates from gas plus the chemical suffixes -ole and -ine.[4][5][6] Petrol derives from the Medieval Latin word petroleum (L. petra, rock + oleum, oil).[7]

Interest in gasoline-like fuels started with the invention of internal combustion engines suitable for use in transportation applications. The so-called Otto engines were developed in Germany during the last quarter of the 19th century. The fuel for these early engines was a relatively volatile hydrocarbon obtained from coal gas. With a boiling point near 85 °C (185 °F) (n-octane boils at 125.62 °C (258.12 °F)[8]), it was well suited for early carburetors (evaporators). The development of a "spray nozzle" carburetor enabled the use of less volatile fuels. Further improvements in engine efficiency were attempted at higher compression ratios, but early attempts were blocked by the premature explosion of fuel, known as knocking. In 1891, the Shukhov cracking process became the world's first commercial method to break down heavier hydrocarbons in crude oil to increase the percentage of lighter products compared to simple distillation.

Chemical analysis and production

[edit]

Commercial gasoline, as well as other liquid transportation fuels, are complex mixtures of hydrocarbons.[9] The performance specification also varies with season, requiring less volatile blends during summer, in order to minimize evaporative losses.

Gasoline is produced in oil refineries. Roughly 72 liters (19 U.S. gal) of gasoline is derived from a 160-liter (42 U.S. gal) barrel of crude oil.[10] Material separated from crude oil via distillation, called virgin or straight-run gasoline, does not meet specifications for modern engines (particularly the octane rating; see below), but can be pooled to the gasoline blend.

The bulk of a typical gasoline consists of a homogeneous mixture of hydrocarbons with between four and twelve carbon atoms per molecule (commonly referred to as C4–C12).[11] It is a mixture of paraffins (alkanes), olefins (alkenes), naphthenes (cycloalkanes), and aromatics. The use of the term paraffin in place of the standard chemical nomenclature alkane is particular to the oil industry (which relies extensively on jargon). The composition of a gasoline depends upon:

- the oil refinery that makes the gasoline, as not all refineries have the same set of processing units;

- the crude oil feed used by the refinery;

- the grade of gasoline sought (in particular, the octane rating).

The various refinery streams blended to make gasoline have different characteristics. Some important streams include the following:

- Straight-run gasoline, sometimes referred to as naphtha (and also light straight run naphtha "LSR" and light virgin naphtha "LVN"), is distilled directly from crude oil. Once the leading source of fuel, naphtha's low octane rating required organometallic fuel additives (primarily tetraethyllead) prior to their phaseout from the gasoline pool which started in 1975 in the United States.[12] Straight run naphtha is typically low in aromatics (depending on the grade of the crude oil stream) and contains some cycloalkanes (naphthenes) and no olefins (alkenes). Between 0 and 20 percent of this stream is pooled into the finished gasoline because the quantity of this fraction in the crude is less than fuel demand and the fraction's Research Octane Number (RON) is too low. The chemical properties (namely RON and Reid vapor pressure (RVP)) of the straight-run gasoline can be improved through reforming and isomerization. However, before feeding those units, the naphtha needs to be split into light and heavy naphtha. Straight-run gasoline can also be used as a feedstock for steam crackers to produce olefins.

- Reformate, produced from straight run gasoline in a catalytic reformer, has a high octane rating with high aromatic content and relatively low olefin content. Most of the benzene, toluene, and xylene (the so-called BTX hydrocarbons) are more valuable as chemical feedstocks and are thus removed to some extent. Also the BTX content is regulated.

- Catalytic cracked gasoline, or catalytic cracked naphtha, produced with a catalytic cracker, has a moderate octane rating, high olefin content, and moderate aromatic content.

- Hydrocrackate (heavy, mid, and light), produced with a hydrocracker, has a medium to low octane rating and moderate aromatic levels.

- Alkylate is produced in an alkylation unit, using isobutane and C3-/C4-olefins as feedstocks. Finished alkylate contains no aromatics or olefins and has a high MON (Motor Octane Number). Alkylate was used during World War II in aviation fuel.[13] Since the late 1980s, it is sold as a specialty fuel for (handheld) gardening and forestry tools with a combustion engine.[14][15]

- Isomerate is obtained by isomerizing low-octane straight-run gasoline into iso-paraffins (non-chain alkanes, such as isooctane). Isomerate has a medium RON and MON, but no aromatics or olefins.

- Butane is usually blended in the gasoline pool, although the quantity of this stream is limited by the RVP specification.

- Oxygenates (more specifically alcohols and esters) are mostly blended into the pool in the US as ethanol. In Europe and other countries, the blends can contain ethanol in addition to Methyl tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE) and Ethyl tert-butyl ether (ETBE). MTBE in the United States was banned by most states in the early-to-mid-2000s.[16] A few countries still allow methanol as well to be blended directly into gasoline, especially in China.[17] More about oxygenates and blending is covered further in this article.

The terms above are the jargon used in the oil industry, and the terminology varies.

Currently, many countries set limits on gasoline aromatics in general, benzene in particular, and olefin (alkene) content. Such regulations have led to an increasing preference for alkane isomers, such as isomerate or alkylate, as their octane rating is higher than n-alkanes. In the European Union, the benzene limit is set at one percent by volume for all grades of automotive gasoline. This is usually achieved by avoiding feeding C6, in particular cyclohexane, to the reformer unit, where it would be converted to benzene. Therefore, only (desulfurized) heavy virgin naphtha (HVN) is fed to the reformer unit.[18]

Gasoline can also contain other organic compounds, such as organic ethers (deliberately added), plus small levels of contaminants, in particular organosulfur compounds (which are usually removed at the refinery).

On average, U.S. petroleum refineries produce about 19 to 20 gallons of gasoline, 11 to 13 gallons of distillate fuel diesel fuel and 3 to 4 gallons of jet fuel from each 42 U.S. gallons (160 liters) barrel of crude oil. The product ratio depends upon the processing in an oil refinery and the crude oil assay.[19]

Physical properties

[edit]

Density

[edit]The specific gravity of gasoline ranges from 0.71 to 0.77,[20] with higher densities having a greater volume fraction of aromatics.[21] Finished marketable gasoline is traded (in Europe) with a standard reference of 0.755 kilograms per liter (6.30 lb/U.S. gal), (7,5668 lb/ imp gal). Its price is escalated or de-escalated according to its actual density.[clarification needed] Because of its low density, gasoline floats on water, and therefore water cannot generally be used to extinguish a gasoline fire unless applied in a fine mist.

Stability

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Quality gasoline should be stable for six months if stored properly, but can degrade over time.[22] Gasoline stored for a year will most likely be able to be burned in an internal combustion engine without too much trouble.[22] Gasoline should ideally be stored in an airtight container (to prevent oxidation or water vapor mixing in with the gas) that can withstand the vapor pressure of the gasoline without venting (to prevent the loss of the more volatile fractions) at a stable cool temperature (to reduce the excess pressure from liquid expansion and to reduce the rate of any decomposition reactions). When gasoline is not stored correctly, gums and solids may result, which can corrode system components and accumulate on wet surfaces, resulting in a condition called "stale fuel". Gasoline containing ethanol is especially subject to absorbing atmospheric moisture, then forming gums, solids, or two phases (a hydrocarbon phase floating on top of a water-alcohol phase).[22]

The presence of these degradation products in the fuel tank or fuel lines plus a carburetor or fuel injection components makes it harder to start the engine or causes reduced engine performance.[23] On resumption of regular engine use, the buildup may or may not be eventually cleaned out by the flow of fresh gasoline. The addition of a fuel stabilizer to gasoline can extend the life of fuel that is not or cannot be stored properly, though removal of all fuel from a fuel system is the only real solution to the problem of long-term storage of an engine or a machine or vehicle. Typical fuel stabilizers are proprietary mixtures containing mineral spirits, isopropyl alcohol, 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene or other additives. Fuel stabilizers are commonly used for small engines, such as lawnmower and tractor engines, especially when their use is sporadic or seasonal (little to no use for one or more seasons of the year). Users have been advised to keep gasoline containers more than half full and properly capped to reduce air exposure, to avoid storage at high temperatures, to run an engine for ten minutes to circulate the stabilizer through all components prior to storage, and to run the engine at intervals to purge stale fuel from the carburetor.[11]

Gasoline stability requirements are set by the standard ASTM D4814. This standard describes the various characteristics and requirements of automotive fuels for use over a wide range of operating conditions in ground vehicles equipped with spark-ignition engines.

Combustion energy content

[edit]A gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine obtains energy from the combustion of gasoline's various hydrocarbons with oxygen from the ambient air, yielding carbon dioxide and water as exhaust. The combustion of octane, a representative species, performs the chemical reaction:

- 2 C8H18 + 25 O2 → 16 CO2 + 18 H2O

By weight, combustion of gasoline releases about 46.7 megajoules per kilogram (13.0 kWh/kg; 21.2 MJ/lb) or by volume 33.6 megajoules per liter (9.3 kWh/L; 127 MJ/U.S. gal; 121,000 BTU/U.S. gal), quoting the lower heating value.[24] Gasoline blends differ, and therefore actual energy content varies according to the season and producer by up to 1.75 percent more or less than the average.[25] On average, about 74 liters (20 U.S. gal) of gasoline are available from a barrel of crude oil (about 46 percent by volume), varying with the quality of the crude and the grade of the gasoline. The remainder is products ranging from tar to naphtha.[26]

A high-octane-rated fuel, such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), has an overall lower power output at the typical 10:1 compression ratio of an engine design optimized for gasoline fuel. An engine tuned for LPG fuel via higher compression ratios (typically 12:1) improves the power output. This is because higher-octane fuels allow for a higher compression ratio without knocking, resulting in a higher cylinder temperature, which improves efficiency. Also, increased mechanical efficiency is created by a higher compression ratio through the concomitant higher expansion ratio on the power stroke, which is by far the greater effect. The higher expansion ratio extracts more work from the high-pressure gas created by the combustion process. An Atkinson cycle engine uses the timing of the valve events to produce the benefits of a high expansion ratio without the disadvantages, chiefly detonation, of a high compression ratio. A high expansion ratio is also one of the two key reasons for the efficiency of diesel engines, along with the elimination of pumping losses due to throttling of the intake airflow.

The lower energy content of LPG by liquid volume in comparison to gasoline is due mainly to its lower density. This lower density is a property of the lower molecular weight of propane (LPG's chief component) compared to gasoline's blend of various hydrocarbon compounds with heavier molecular weights than propane. Conversely, LPG's energy content by weight is higher than gasoline's due to a higher hydrogen-to-carbon ratio.

Molecular weights of the species in the representative octane combustion are 114, 32, 44, and 18 for C8H18, O2, CO2, and H2O, respectively; therefore one kilogram (2.2 lb) of fuel reacts with 3.51 kilograms (7.7 lb) of oxygen to produce 3.09 kilograms (6.8 lb) of carbon dioxide and 1.42 kilograms (3.1 lb) of water.

Octane rating

[edit]Spark-ignition engines are designed to burn gasoline in a controlled process called deflagration. However, the unburned mixture may autoignite by pressure and heat alone, rather than igniting from the spark plug at exactly the right time, causing a rapid pressure rise that can damage the engine. This is often referred to as engine knocking or end-gas knock. Knocking can be reduced by increasing the gasoline's resistance to autoignition, which is expressed by its octane rating. A detailed analysis further explores the conditions where premium fuel provides actual performance benefits versus when it is unnecessary.[27]

Octane rating is measured relative to a mixture of 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (an isomer of octane) and n-heptane. There are different conventions for expressing octane ratings, so the same physical fuel may have several different octane ratings based on the measure used. One of the best known is the research octane number (RON).

The octane rating of typical commercially available gasoline varies by country. In Finland, Sweden, and Norway, 95 RON is the standard for regular unleaded gasoline and 98 RON is also available as a more expensive option.

In the United Kingdom, over 95 percent of gasoline sold has 95 RON and is marketed as Unleaded or Premium Unleaded. Super Unleaded, with 97/98 RON and branded high-performance fuels (e.g., Shell V-Power, BP Ultimate) with 99 RON make up the balance. Gasoline with 102 RON may rarely be available for racing purposes.[28][29][30]

In the U.S., octane ratings in unleaded fuels vary between 85[31] and 87 AKI (91–92 RON) for regular, 89–90 AKI (94–95 RON) for mid-grade (equivalent to European regular), up to 90–94 AKI (95–99 RON) for premium (European premium).

| 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 102 | |

| Scandinavian | Regular | Premium | ||||||||||

| UK | Regular | Premium | Super | High-performance | ||||||||

| USA | Regular | Mid-grade | Premium | |||||||||

As South Africa's largest city, Johannesburg, is located on the Highveld at 1,753 meters (5,751 ft) above sea level, the Automobile Association of South Africa recommends 95-octane gasoline at low altitude and 93-octane for use in Johannesburg because "The higher the altitude the lower the air pressure, and the lower the need for a high octane fuel as there is no real performance gain".[32]

Octane rating became important as the military sought higher output for aircraft engines in the late 1920s and the 1940s. A higher octane rating allows a higher compression ratio or supercharger boost, and thus higher temperatures and pressures, which translate to higher power output. Some scientists[who?] even predicted that a nation with a good supply of high-octane gasoline would have the advantage in air power. In 1943, the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine produced 980 kilowatts (1,320 hp) using 100 RON fuel from a modest 27 liters (1,600 cu in) displacement. By the time of Operation Overlord, both the RAF and USAAF were conducting some operations in Europe using 150 RON fuel (100/150 avgas), obtained by adding 2.5 percent aniline to 100-octane avgas.[33] By this time, the Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 was developing 1,500 kilowatts (2,000 hp) using this fuel.

Additives

[edit]Antiknock additives

[edit]Tetraethyl lead

[edit]

Gasoline, when used in high-compression internal combustion engines, tends to auto-ignite or "detonate" causing damaging engine knocking (also called "pinging" or "pinking"). To address this problem, tetraethyl lead (TEL) was widely adopted as an additive for gasoline in the 1920s. With a growing awareness of the seriousness of the extent of environmental and health damage caused by lead compounds, however, and the incompatibility of lead with catalytic converters, governments began to mandate reductions in gasoline lead.

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency issued regulations to reduce the lead content of leaded gasoline over a series of annual phases, scheduled to begin in 1973 but delayed by court appeals until 1976. By 1995, leaded fuel accounted for only 0.6 percent of total gasoline sales and under 1,800 metric tons (2,000 short tons; 1,800 long tons) of lead per year. From 1 January 1996, the U.S. Clean Air Act banned the sale of leaded fuel for use in on-road vehicles in the U.S. The use of TEL also necessitated other additives, such as dibromoethane.

European countries began replacing lead-containing additives by the end of the 1980s and, by the end of the 1990s, leaded gasoline was banned within the entire European Union with an exception for Avgas 100LL for general aviation.[34] The UAE started to switch to unleaded in the early 2000s.[35]

Reduction in the average lead content of human blood may be a major cause for falling violent crime rates around the world[36] including South Africa.[37] A study found a correlation between leaded gasoline usage and violent crime (see Lead–crime hypothesis).[38][39] Other studies found no correlation.

In August 2021, the UN Environment Programme announced that leaded gasoline had been eradicated worldwide, with Algeria being the last country to deplete its reserves. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the eradication of leaded petrol an "international success story". He also added: "Ending the use of leaded petrol will prevent more than one million premature deaths each year from heart disease, strokes and cancer, and it will protect children whose IQs are damaged by exposure to lead". Greenpeace called the announcement "the end of one toxic era".[40] However, leaded gasoline continues to be used in aeronautic, auto racing, and off-road applications.[41] The use of leaded additives is still permitted worldwide for the formulation of some grades of aviation gasoline such as 100LL, because the required octane rating is difficult to reach without the use of leaded additives.

Different additives have replaced lead compounds. The most popular additives include aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers (MTBE and ETBE), and alcohols, most commonly ethanol.

Lead replacement petrol

[edit]Lead replacement petrol (LRP) was developed for vehicles designed to run on leaded fuels and incompatible with unleaded fuels. Rather than tetraethyllead, it contains other metals such as potassium compounds or methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT); these are purported to buffer soft exhaust valves and seats so that they do not suffer recession due to the use of unleaded fuel.

LRP was marketed during and after the phaseout of leaded motor fuels in the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, and some other countries.[vague] Consumer confusion led to a widespread mistaken preference for LRP rather than unleaded,[42] and LRP was phased out 8 to 10 years after the introduction of unleaded.[43]

Leaded gasoline was withdrawn from sale in Britain after 31 December 1999, seven years after EEC regulations signaled the end of production for cars using leaded gasoline in member states. At this stage, a large percentage of cars from the 1980s and early 1990s which ran on leaded gasoline were still in use, along with cars that could run on unleaded fuel. However, the declining number of such cars on British roads saw many gasoline stations withdrawing LRP from sale by 2003.[44]

MMT

[edit]Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT) is used in Canada and the U.S. to boost octane rating.[45] Its use in the U.S. has been restricted by regulations, although it is currently allowed.[46] Its use in the European Union is restricted by Article 8a of the Fuel Quality Directive[47] following its testing under the Protocol for the evaluation of effects of metallic fuel-additives on the emissions performance of vehicles.[48]

Fuel stabilizers (antioxidants and metal deactivators)

[edit]

Gummy, sticky resin deposits result from oxidative degradation of gasoline during long-term storage. These harmful deposits arise from the oxidation of alkenes and other minor components in gasoline[citation needed] (see drying oils). Improvements in refinery techniques have generally reduced the susceptibility of gasolines to these problems. Previously, catalytically or thermally cracked gasolines were most susceptible to oxidation. The formation of gums is accelerated by copper salts, which can be neutralized by additives called metal deactivators.

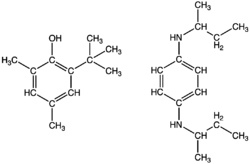

This degradation can be prevented through the addition of 5–100 ppm of antioxidants, such as phenylenediamines and other amines.[11] Hydrocarbons with a bromine number of 10 or above can be protected with the combination of unhindered or partially hindered phenols and oil-soluble strong amine bases, such as hindered phenols. "Stale" gasoline can be detected by a colorimetric enzymatic test for organic peroxides produced by oxidation of the gasoline.[49]

Gasolines are also treated with metal deactivators, which are compounds that sequester (deactivate) metal salts that otherwise accelerate the formation of gummy residues. The metal impurities might arise from the engine itself or as contaminants in the fuel.

Detergents

[edit]Gasoline, as delivered at the pump, also contains additives to reduce internal engine carbon buildups, improve combustion and allow easier starting in cold climates. High levels of detergent can be found in Top Tier Detergent Gasolines. The specification for Top Tier Detergent Gasolines was developed by four automakers: GM, Honda, Toyota, and BMW. According to the bulletin, the minimal U.S. EPA requirement is not sufficient to keep engines clean.[50] Typical detergents include alkylamines and alkyl phosphates at a level of 50–100 ppm.[11]

Ethanol

[edit]

European Union

[edit]In the EU, 5 percent ethanol can be added within the common gasoline spec (EN 228). Discussions are ongoing to allow 10 percent blending of ethanol (available in Finnish, French and German gasoline stations). In Finland, most gasoline stations sell 95E10, which is 10 percent ethanol, and 98E5, which is 5 percent ethanol. Most gasoline sold in Sweden has 5–15 percent ethanol added. Three different ethanol blends are sold in the Netherlands—E5, E10 and hE15. The last of these differs from standard ethanol–gasoline blends in that it consists of 15 percent hydrous ethanol (i.e., the ethanol–water azeotrope) instead of the anhydrous ethanol traditionally used for blending with gasoline.

From 2009 to 2022, renewable percentage in gasoline slowly increased from 5% to 10%, even though EU-produced ethanol can achieve a climate-neutral production capability and most EU cars can use E10. E10 availability is low even in larger countries like Germany (26%) and France (58%). 8 countries in the EU have not adopted E10 as of 2024.[51]

Brazil

[edit]The Brazilian National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) requires gasoline for automobile use to have 27.5 percent of ethanol added to its composition.[52] Pure hydrated ethanol is also available as a fuel.

Australia

[edit]Australia uses both E10 (up to 10% ethanol) and E85 (up to 85% ethanol) in its gasoline. New South Wales mandated biofuel in its Biofuels Act 2007, and Queensland had a biofuel mandate since 2017. Fuel pumps must be clearly labeled with its ethanol/biodiesel content.[53]

U.S.

[edit]The federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) effectively requires refiners and blenders to blend renewable biofuels (mostly ethanol) with gasoline, sufficient to meet a growing annual target of total gallons blended. Although the mandate does not require a specific percentage of ethanol, annual increases in the target combined with declining gasoline consumption have caused the typical ethanol content in gasoline to approach 10 percent. Most fuel pumps display a sticker that states that the fuel may contain up to 10 percent ethanol, an intentional disparity that reflects the varying actual percentage. In parts of the U.S., ethanol is sometimes added to gasoline without an indication that it is a component.

India

[edit]In October 2007, the Government of India decided to make five percent ethanol blending (with gasoline) mandatory. Currently, 10 percent ethanol blended product (E10) is being sold in various parts of the country.[54][55] Ethanol has been found in at least one study to damage catalytic converters.[56]

Dyes

[edit]Though gasoline is a naturally colorless liquid, many gasolines are dyed in various colors to indicate their composition and acceptable uses. In Australia, the lowest grade of gasoline (RON 91) was dyed a light shade of red/orange, but is now the same color as the medium grade (RON 95) and high octane (RON 98), which are dyed yellow.[57] In the U.S., aviation gasoline (avgas) is dyed to identify its octane rating and to distinguish it from kerosene-based jet fuel, which is left colorless.[58] In Canada, the gasoline for marine and farm use is dyed red and is not subject to fuel excise tax in most provinces.[59]

Oxygenate blending

[edit]Oxygenate blending adds oxygen-bearing compounds such as methanol, MTBE, ETBE, TAME, TAEE, ethanol, and biobutanol. The presence of these oxygenates reduces the amount of carbon monoxide and unburned fuel in the exhaust. In many areas throughout the U.S., oxygenate blending is mandated by EPA regulations to reduce smog and other airborne pollutants. For example, in Southern California fuel must contain two percent oxygen by weight, resulting in a mixture of 5.6 percent ethanol in gasoline. The resulting fuel is often known as reformulated gasoline (RFG) or oxygenated gasoline, or, in the case of California, California reformulated gasoline (CARBOB). The federal requirement that RFG contain oxygen was dropped on 6 May 2006 because the industry had developed VOC-controlled RFG that did not need additional oxygen.[60]

MTBE was phased out in the U.S. due to groundwater contamination and the resulting regulations and lawsuits. Ethanol and, to a lesser extent, ethanol-derived ETBE are common substitutes. A common ethanol-gasoline mix of 10 percent ethanol mixed with gasoline is called gasohol or E10, and an ethanol-gasoline mix of 85 percent ethanol mixed with gasoline is called E85. The most extensive use of ethanol takes place in Brazil, where the ethanol is derived from sugarcane. In 2004, over 13 billion liters (3.4×109 U.S. gal) of ethanol was produced in the U.S. for fuel use, mostly from corn and sold as E10. E85 is slowly becoming available in much of the U.S., though many of the relatively few stations vending E85 are not open to the general public.[61]

The use of bioethanol and bio-methanol, either directly or indirectly by conversion of ethanol to bio-ETBE, or methanol to bio-MTBE is encouraged by the European Union Directive on the Promotion of the use of biofuels and other renewable fuels for transport. Since producing bioethanol from fermented sugars and starches involves distillation, though, ordinary people in much of Europe cannot legally ferment and distill their own bioethanol at present (unlike in the U.S., where getting a BATF distillation permit has been easy since the 1973 oil crisis).

Safety

[edit]

Toxicity

[edit]The safety data sheet for a 2003 Texan unleaded gasoline shows at least 15 hazardous chemicals occurring in various amounts, including benzene (up to five percent by volume), toluene (up to 35 percent by volume), naphthalene (up to one percent by volume), trimethylbenzene (up to seven percent by volume), methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (up to 18 percent by volume, in some states), and about 10 others.[62] Hydrocarbons in gasoline generally exhibit low acute toxicities, with LD50 of 700–2700 mg/kg for simple aromatic compounds.[63] Benzene and many antiknocking additives are carcinogenic.

People can be exposed to gasoline in the workplace by swallowing it, breathing in vapors, skin contact, and eye contact. Gasoline is toxic. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has also designated gasoline as a carcinogen.[64] Physical contact, ingestion, or inhalation can cause health problems. Since ingesting large amounts of gasoline can cause permanent damage to major organs, a call to a local poison control center or emergency room visit is indicated.[65]

Contrary to common misconception, swallowing gasoline does not generally require special emergency treatment, and inducing vomiting does not help, and can make it worse. According to poison specialist Brad Dahl, "even two mouthfuls wouldn't be that dangerous as long as it goes down to your stomach and stays there or keeps going". The U.S. CDC's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry says not to induce vomiting, lavage, or administer activated charcoal.[66][67]

Inhalation for intoxication

[edit]Inhaled (huffed) gasoline vapor is a common intoxicant. Users concentrate and inhale gasoline vapor in a manner not intended by the manufacturer to produce euphoria and intoxication. Gasoline inhalation has become epidemic in some poorer communities and indigenous groups in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and some Pacific Islands.[68] The practice is thought to cause severe organ damage, along with other effects such as intellectual disability and various cancers.[69][70][71][72]

In Canada, Native children in the isolated Northern Labrador community of Davis Inlet were the focus of national concern in 1993, when many were found to be sniffing gasoline. The Canadian and provincial Newfoundland and Labrador governments intervened on several occasions, sending many children away for treatment. Despite being moved to the new community of Natuashish in 2002, serious inhalant abuse problems have continued. Similar problems were reported in Sheshatshiu in 2000 and also in Pikangikum First Nation.[73] In 2012, the issue once again made the news media in Canada.[74]

Australia has long faced a petrol (gasoline) sniffing problem in isolated and impoverished aboriginal communities. Although some sources argue that sniffing was introduced by U.S. servicemen stationed in the nation's Top End during World War II[75] or through experimentation by 1940s-era Cobourg Peninsula sawmill workers,[76] other sources claim that inhalant abuse (such as glue inhalation) emerged in Australia in the late 1960s.[77] Chronic, heavy petrol sniffing appears to occur among remote, impoverished indigenous communities, where the ready accessibility of petrol has helped to make it a common substance for abuse.

In Australia, petrol sniffing now occurs widely throughout remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, northern parts of South Australia, and Queensland.[78] The number of people sniffing petrol goes up and down over time as young people experiment or sniff occasionally. "Boss", or chronic, sniffers may move in and out of communities; they are often responsible for encouraging young people to take it up.[79] In 2005, the Government of Australia and BP Australia began the usage of Opal fuel in remote areas prone to petrol sniffing.[80] Opal is a non-sniffable fuel (which is much less likely to cause a high) and has made a difference in some indigenous communities.

Flammability

[edit]

Gasoline is flammable with low flash point of −23 °C (−9 °F). Gasoline has a lower explosive limit of 1.4 percent by volume and an upper explosive limit of 7.6 percent. If the concentration is below 1.4 percent, the air-gasoline mixture is too lean and does not ignite. If the concentration is above 7.6 percent, the mixture is too rich and also does not ignite. However, gasoline vapor rapidly mixes and spreads with air, making unconstrained gasoline quickly flammable.

Gasoline exhaust

[edit]The exhaust gas generated by burning gasoline is harmful to both the environment and to human health. After CO is inhaled into the human body, it readily combines with hemoglobin in the blood, and its affinity is 300 times that of oxygen. Therefore, the hemoglobin in the lungs combines with CO instead of oxygen, causing the human body to be hypoxic, causing headaches, dizziness, vomiting, and other poisoning symptoms. In severe cases, it may lead to death.[81][82] Hydrocarbons only affect the human body when their concentration is quite high, and their toxicity level depends on the chemical composition. The hydrocarbons produced by incomplete combustion include alkanes, aromatics, and aldehydes. Among them, a concentration of methane and ethane over 35 g/m3 (0.035 oz/cu ft) will cause loss of consciousness or suffocation, a concentration of pentane and hexane over 45 g/m3 (0.045 oz/cu ft) will have an anesthetic effect, and aromatic hydrocarbons will have more serious effects on health, blood toxicity, neurotoxicity, and cancer. If the concentration of benzene exceeds 40 ppm, it can cause leukemia, and xylene can cause headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Human exposure to large amounts of aldehydes can cause eye irritation, nausea, and dizziness. In addition to carcinogenic effects, long-term exposure can cause damage to the skin, liver, kidneys, and cataracts.[83] After NOx enters the alveoli, it has a severe stimulating effect on the lung tissue. It can irritate the conjunctiva of the eyes, cause tearing, and cause pink eyes. It also has a stimulating effect on the nose, pharynx, throat, and other organs. It can cause acute wheezing, breathing difficulties, red eyes, sore throat, and dizziness causing poisoning.[83][84] Fine particulates are also dangerous to health.[85]

Environmental effect

[edit]The air pollution in many large cities has changed from coal-burning pollution to "motor vehicle pollution". In the U.S., transportation is the largest source of carbon emissions, accounting for 30 percent of the total carbon footprint of the U.S.[86] Combustion of gasoline produces 2.35 kilograms per liter (19.6 lb/U.S. gal) of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.[87][88]

Unburnt gasoline and evaporation from the tank, when in the atmosphere, react in sunlight to produce photochemical smog. Vapor pressure initially rises with some addition of ethanol to gasoline, but the increase is greatest at 10 percent by volume.[89] At higher concentrations of ethanol above 10 percent, the vapor pressure of the blend starts to decrease. At a 10 percent ethanol by volume, the rise in vapor pressure may potentially increase the problem of photochemical smog. This rise in vapor pressure could be mitigated by increasing or decreasing the percentage of ethanol in the gasoline mixture. The chief risks of such leaks come not from vehicles, but gasoline delivery truck accidents and leaks from storage tanks. Because of this risk, most (underground) storage tanks now have extensive measures in place to detect and prevent any such leaks, such as monitoring systems (Veeder-Root, Franklin Fueling).

Production of gasoline consumes 1.5 liters per kilometer (0.63 U.S. gal/mi) of water by driven distance.[90]

Gasoline use causes a variety of deleterious effects to the human population and to the climate generally. The harms imposed include a higher rate of premature death and ailments, such as asthma, caused by air pollution, higher healthcare costs for the public generally, decreased crop yields, missed work and school days due to illness, increased flooding and other extreme weather events linked to global climate change, and other social costs. The costs imposed on society and the planet are estimated to be $3.80 per gallon of gasoline, in addition to the price paid at the pump by the user. The damage to the health and climate caused by a gasoline-powered vehicle greatly exceeds that caused by electric vehicles.[91][92]

Gasoline can be released into the environment as an uncombusted liquid fuel, as a flammable liquid, or as a vapor by way of leakages occurring during its production, handling, transport and delivery.[93] Gasoline contains known carcinogens,[94][95][96] and gasoline exhaust is a health risk.[85] Gasoline is often used as a recreational inhalant and can be harmful or fatal when used in such a manner.[97] When burned, one liter (0.26 U.S. gal) of gasoline emits about 2.3 kilograms (5.1 lb) of CO2, a greenhouse gas, contributing to human-caused climate change.[98][99] Oil products, including gasoline, were responsible for about 32% of CO2 emissions worldwide in 2021.[100]

Carbon dioxide

[edit]About 2.353 kilograms per liter (19.64 lb/U.S. gal) of carbon dioxide (CO2) are produced from burning gasoline that does not contain ethanol.[88] Most of the retail gasoline now sold in the U.S. contains about 10 percent fuel ethanol (or E10) by volume.[88] Burning E10 produces about 2.119 kilograms per liter (17.68 lb/U.S. gal) of CO2 that is emitted from the fossil fuel content. If the CO2 emissions from ethanol combustion are considered, then about 2.271 kilograms per liter (18.95 lb/U.S. gal) of CO2 are produced when E10 is combusted.[88]

Worldwide 7 liters of gasoline are burnt for every 100 km driven by cars and vans.[101]

In 2021, the International Energy Agency stated, "To ensure fuel economy and CO2 emissions standards are effective, governments must continue regulatory efforts to monitor and reduce the gap between real-world fuel economy and rated performance."[101]

Contamination of soil and water

[edit]Gasoline enters the environment through the soil, groundwater, surface water, and air. Therefore, humans may be exposed to gasoline through methods such as breathing, eating, and skin contact. For example, using gasoline-filled equipment, such as lawnmowers, drinking gasoline-contaminated water close to gasoline spills or leaks to the soil, working at a gasoline station, inhaling gasoline volatile gas when refueling at a gasoline station is the easiest way to be exposed to gasoline.[102]

Use and pricing

[edit]The International Energy Agency said in 2021 that "road fuels should be taxed at a rate that reflects their impact on people's health and the climate".[101]

Europe

[edit]Countries in Europe impose substantially higher taxes on fuels such as gasoline when compared to the U.S. The price of gasoline in Europe is typically higher than that in the U.S. due to this difference.[103]

U.S.

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2016) |

From 1998 to 2004, the price of gasoline fluctuated between $0.26 and $0.53 per liter ($1 and $2/U.S. gal).[104] After 2004, the price increased until the average gasoline price reached a high of $1.09 per liter ($4.11/U.S. gal) in mid-2008 but receded to approximately $0.69 per liter ($2.60/U.S. gal) by September 2009.[104] The U.S. experienced an upswing in gasoline prices through 2011,[105] and, by 1 March 2012, the national average was $0.99 per liter ($3.74/U.S. gal). California prices are higher because the California government mandates unique California gasoline formulas and taxes.[106]

In the U.S., most consumer goods bear pre-tax prices, but gasoline prices are posted with taxes included. Taxes are added by federal, state, and local governments. As of 2009[update], the federal tax was $0.049 per liter ($0.184/U.S. gal) for gasoline and $0.064 per liter ($0.244/U.S. gal) for diesel (excluding red diesel).[107]

About nine percent of all gasoline sold in the U.S. in May 2009 was premium grade, according to the Energy Information Administration. Consumer Reports magazine says, "If [your owner's manual] says to use regular fuel, do so—there's no advantage to a higher grade."[108] The Associated Press said premium gas—which has a higher octane rating and costs more per gallon than regular unleaded—should be used only if the manufacturer says it is "required".[109] Cars with turbocharged engines and high compression ratios often specify premium gasoline because higher octane fuels reduce the incidence of "knock", or fuel pre-detonation.[110] The price of gasoline varies considerably between the summer and winter months.[111]

There is a considerable difference between summer oil and winter oil in gasoline vapor pressure (Reid Vapor Pressure, RVP), which is a measure of how easily the fuel evaporates at a given temperature. The higher the gasoline volatility (the higher the RVP), the easier it is to evaporate. The conversion between the two fuels occurs twice a year, once in autumn (winter mix) and the other in spring (summer mix). The winter blended fuel has a higher RVP because the fuel must be able to evaporate at a low temperature for the engine to run normally. If the RVP is too low on a cold day, the vehicle will be difficult to start; however, the summer blended gasoline has a lower RVP. It prevents excessive evaporation when the outdoor temperature rises, reduces ozone emissions, and reduces smog levels. At the same time, vapor lock is less likely to occur in hot weather.[112]

Gasoline production by country

[edit]| Country | Gasoline production | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrels (thousands) |

m3 (thousands) |

ft3 (thousands) |

kL | |

| U.S. | 8,921 | 1,418.3 | 50,090 | 1,418.3 |

| China | 2,578 | 409.9 | 14,470 | 409.9 |

| Japan | 920 | 146 | 5,200 | 146 |

| Russia | 910 | 145 | 5,100 | 145 |

| India | 755 | 120.0 | 4,240 | 120.0 |

| Canada | 671 | 106.7 | 3,770 | 106.7 |

| Brazil | 533 | 84.7 | 2,990 | 84.7 |

| Germany | 465 | 73.9 | 2,610 | 73.9 |

| Saudi Arabia | 441 | 70.1 | 2,480 | 70.1 |

| Mexico | 407 | 64.7 | 2,290 | 64.7 |

| South Korea | 397 | 63.1 | 2,230 | 63.1 |

| Iran | 382 | 60.7 | 2,140 | 60.7 |

| UK | 364 | 57.9 | 2,040 | 57.9 |

| Italy | 343 | 54.5 | 1,930 | 54.5 |

| Venezuela | 277 | 44.0 | 1,560 | 44.0 |

| France | 265 | 42.1 | 1,490 | 42.1 |

| Singapore | 249 | 39.6 | 1,400 | 39.6 |

| Australia | 241 | 38.3 | 1,350 | 38.3 |

| Indonesia | 230 | 37 | 1,300 | 37 |

| Taiwan | 174 | 27.7 | 980 | 27.7 |

| Thailand | 170 | 27 | 950 | 27 |

| Spain | 169 | 26.9 | 950 | 26.9 |

| Netherlands | 148 | 23.5 | 830 | 23.5 |

| South Africa | 135 | 21.5 | 760 | 21.5 |

| Argentina | 122 | 19.4 | 680 | 19.4 |

| Sweden | 112 | 17.8 | 630 | 17.8 |

| Greece | 108 | 17.2 | 610 | 17.2 |

| Belgium | 105 | 16.7 | 590 | 16.7 |

| Malaysia | 103 | 16.4 | 580 | 16.4 |

| Finland | 100 | 16 | 560 | 16 |

| Belarus | 92 | 14.6 | 520 | 14.6 |

| Turkey | 92 | 14.6 | 520 | 14.6 |

| Colombia | 85 | 13.5 | 480 | 13.5 |

| Poland | 83 | 13.2 | 470 | 13.2 |

| Norway | 77 | 12.2 | 430 | 12.2 |

| Kazakhstan | 71 | 11.3 | 400 | 11.3 |

| Algeria | 70 | 11 | 390 | 11 |

| Romania | 70 | 11 | 390 | 11 |

| Oman | 69 | 11.0 | 390 | 11.0 |

| Egypt | 66 | 10.5 | 370 | 10.5 |

| UAE | 66 | 10.5 | 370 | 10.5 |

| Chile | 65 | 10.3 | 360 | 10.3 |

| Turkmenistan | 61 | 9.7 | 340 | 9.7 |

| Kuwait | 57 | 9.1 | 320 | 9.1 |

| Iraq | 56 | 8.9 | 310 | 8.9 |

| Vietnam | 52 | 8.3 | 290 | 8.3 |

| Lithuania | 49 | 7.8 | 280 | 7.8 |

| Denmark | 48 | 7.6 | 270 | 7.6 |

| Qatar | 46 | 7.3 | 260 | 7.3 |

Comparison with other fuels

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

Below is a table of the energy density (per volume) and specific energy (per mass) of various transportation fuels as compared with gasoline. In the rows with gross and net, they are from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory's Transportation Energy Data Book.[114]

| Fuel type | Energy density | Specific energy | RON | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross | Net | Gross | Net | ||||||

| MJ/L | BTU / U.S. gal | MJ/L | BTU / U.S. gal | MJ/kg | BTU/lb | MJ/kg | BTU/lb | ||

| Gasoline | 34.8 | 125,000 | 32.2 | 115,400 | 44.4 | 19,100[115] | 41.1 | 17,700 | 91–98 |

| Autogas (LPG)[a] | 26.8 | 96,000 | 46 | 20,000 | 108 | ||||

| Ethanol | 21.2 | 76,000[115] | 21.1 | 75,700 | 26.8 | 11,500[115] | 26.7 | 11,500 | 108.7[116] |

| Methanol | 17.9 | 64,000 | 15.8 | 56,600 | 22.6 | 9,700 | 19.9 | 8,600 | 123 |

| Butanol | 29.2 | 105,000 | 36.6 | 15,700 | 91–99[clarification needed] | ||||

| Gasohol | 31.2 | 112,000 | 31.3 | 112,400 | 93–94[clarification needed] | ||||

| Diesel[b] | 38.6 | 138,000 | 35.9 | 128,700 | 45.4 | 19,500 | 42.2 | 18,100 | 25 |

| Biodiesel | 33.3–35.7 | 119,000–128,000[117][clarification needed] | 32.6 | 117,100 | |||||

| Avgas | 33.5 | 120,000 | 31 | 112,000 | 46.8 | 20,100 | 43.3 | 18,600 | |

| Jet A | 35.1 | 126,000 | 43.8 | 18,800 | |||||

| Jet B | 35.5 | 127,500 | 33.1 | 118,700 | |||||

| LNG | 25.3 | 91,000 | 55 | 24,000 | |||||

| LPG | 25.4 | 91,300 | 23.3 | 83,500 | 46.1 | 19,800 | 42.3 | 18,200 | |

| CGH2[c] | 10.1 | 36,000 | 0.036 | 130[118] | 142 | 61,000 | 0.506 | 218 | |

See also

[edit]Chevron published a free technical guide Motor Gasolines Technical Review[inappropriate external link?] using common language that explains gasoline production, blending, and combustion in an engine.[promotion?] The report covers the US and other locations globally.

- Aviation fuel – Fuel used to power aircraft

- Butanol fuel – Fuel for internal combustion engines – replacement fuel for use in unmodified gasoline engines

- Biogasoline – Gasoline produced from biomass - petrol derived from biomass such as algae

- Diesel fuel – Liquid fuel used in diesel engines

- Filling station – Facility that sells gasoline and diesel

- Fuel dispenser – Machine at a filling station that is used to pump fuels

- Fuel saving device – Product sold in the automotive aftermarket

- Gas to liquids – Conversion of natural gas to liquid petroleum products

- Gasoline and diesel usage and pricing

- Gasoline gallon equivalent – Amount of alternative fuel it takes to equal the energy content of one liquid gallon of gasoline

- Hydrogen fuel – Using hydrogen to decarbonize more sectors

- Internal combustion engine (ICE) – Engine in which fuel combusts with an oxidizer

- Jerrycan – Robust pressed steel liquid container

- List of automotive fuel retailers

- List of gasoline additives

- Natural-gas condensate § Drip gas – Low-density mixture of hydrocarbon liquids

- Synthetic gasoline – Fuel from carbon monoxide and hydrogen

- Octane rating – Standard measure of the performance of an engine or aviation fuel

- World oil market chronology from 2003 – Chronology of events affecting the oil market

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Consisting mostly of C3 and C4 hydrocarbons

- ^ Diesel fuel is not used in a gasoline engine, so its low octane rating is not an issue; the relevant metric for diesel engines is the cetane number.

- ^ at −253.2 °C (−423.8 °F)

References

[edit]- ^ Gary, James H.; Handwerk, Glenn E. (2001). Petroleum refining: technology and economics (4. ed.). New York Basel: Dekker. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8247-0482-7.

- ^ "Why small planes still use leaded fuel decades after phase-out in cars". NBC News. 22 April 2021. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Race Fuel 101: Lead and Leaded Racing Fuels". Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "gasoline". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "gasoline". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ gasoline". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2024.

- ^ "petroleum". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "N-OCTANE / CAMEO Chemicals / NOAA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Hydrocarbon Gas Liquids Explained - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Gasoline—a petroleum product". U.S. Energy Information Administration website. U.S. Energy Information Administration. 12 August 2016. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Werner Dabelstein, Arno Reglitzky, Andrea Schütze and Klaus Reders "Automotive Fuels" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_719.pub2

- ^ Hofverberg, Elin (14 April 2022). "The History of the Elimination of Leaded Gasoline | In Custodia Legis". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "Alkylate: Understanding a Key Component of Cleaner Gasoline". American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers. 6 August 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Specially designed fuel for cleaner oceans". AlkylateFuel.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "The story behind Aspen Alkylate Fuel". AspenFuel.co.uk. 5 June 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ US EPA (June 2004). "State Actions Banning MTBE (Statewide)" (PDF). EPA Archives.

- ^ "China's use of methanol in liquid fuels has grown rapidly since 2000 - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ^ Huess Hedlund, Frank; Boier Pedersena, Jan; Sinc, Gürkan; Garde, Frits G.; Kragha, Eva K.; Frutiger, Jérôme (February 2019). "Puncture of an import gasoline pipeline—Spray effects may evaporate more fuel than a Buncefield-type tank overfill event" (PDF). Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 122: 33–47. Bibcode:2019PSEP..122...33H. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2018.11.007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Refining crude oil—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Bell Fuels. "Lead-Free gasoline Material Safety Data Sheet". NOAA. Archived from the original on 20 August 2002.

- ^ Demirel, Yaşar (26 January 2012). Energy: Production, Conversion, Storage, Conservation, and Coupling. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4471-2371-2. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Crisara, Matt (6 March 2023). "It's True: Gasoline Has an Expiration Date". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 15 January 2025. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ Pradelle, Florian; Braga, Sergio L.; Martins, Ana Rosa F. A.; Turkovics, Franck; Pradelle, Renata N. C. (3 November 2015). "Gum Formation in Gasoline and Its Blends: A Review". Energy & Fuels. 29 (12): 7753–7770. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b01894.

- ^ "Energy Information Administration". www.eia.gov. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Fuel Properties Comparison" (PDF). Alternative Fuels Data Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ "Oil Industry Statistics from Gibson Consulting". Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Gomez, Aly (6 February 2025). "Premium vs. Regular Gas: Are You Getting What You Pay For?". Substack. Retrieved 8 February 2025.

- ^ "Quality of petrol and diesel fuel used for road transport in the European Union (Reporting year 2013)". European Commission. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Types Of Car Fuel". Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Sunoco CFR Racing Fuel". Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Ryan Lengerich Journal staff (17 July 2012). "85-octane warning labels not posted at many gasoline stations". Rapid City Journal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015.

- ^ "95/93 – What is the Difference, Really?". Automobile Association of South Africa (AA). Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Hearst Magazines (April 1936). "Popular Mechanics". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines: 524–. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013.

- ^ Calderwood, Dave (8 March 2022). "Europe moves to ban lead in avgas". FLYER. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "UAE switches to unleaded fuel". January 2003. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (22 April 2013). "Lead abatement, alcohol taxes and 10 other ways to reduce the crime rate without annoying the NRA". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Marrs, Dave (22 January 2013). "Ban on lead may yet give us respite from crime". Business Day. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Reyes, J. W. (2007). "The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. "a" ref citing Pirkle, Brody, et al. (1994). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Ban on leaded petrol 'has cut crime rates around the world'". 28 October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Highly polluting leaded petrol now eradicated from the world, says UN". BBC News. 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Miranda, Leticia; Farivar, Cyrus (12 April 2021). "Leaded gas was phased out 25 years ago. Why are these planes still using toxic fuel?". NBC News. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Seggie, Eleanor (5 August 2011). "More than 20% of SA cars still using lead-replacement petrol but only 1% need it". Engineering News. South Africa. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Clark, Andrew (14 August 2002). "Petrol for older cars about to disappear". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "AA warns over lead replacement fuel". The Daily Telegraph. London. 15 August 2002. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Hollrah, Don P.; Burns, Allen M. (11 March 1991). "MMT Increases Octane While Reducing Emissions". www.ogj.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016.

- ^ "EPA Comments on the Gasoline Additive MMT". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 5 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016.

- ^ "Directive 2009/30/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009". Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Protocol for the Evaluation of Effects of Metallic Fuel-Additives on the Emissions Performance of Vehicles" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ A1 AU 2000/72399 A1 Gasoline test kit

- ^ "Top Tier Detergent Gasoline (Deposits, Fuel Economy, No Start, Power, Performance, Stall Concerns)", GM Bulletin, 04-06-04-047, 06-Engine/Propulsion System, June 2004

- ^ "Ethanol in gasoline: an immediate solution for renewables in road transport, the potential of E10 deployment in the EU – Summary of webinar by ETIP Bioenergy Working Group 3 – ETIP Bioenergy". Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ "MEDIDA PROVISÓRIA nº 532, de 2011". senado.gov.br. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Ethanol and other biofuels". Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. 20 February 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Government to take a call on ethanol price soon". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 21 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "India to raise ethanol blending in gasoline to 10%". 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "European Biogas Association" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "The Color of Australian Unleaded Petrol Is Changing To Red/Orange" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "EAA – Avgas Grades". 17 May 2008. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Fuel Taxes & Road Expenditures: Making the Link" (PDF). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ "Removal of Reformulated Gasoline Oxygen Content Requirement (national) and Revision of Commingling Prohibition to Address Non-0xygenated Reformulated Gasoline (national)". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 22 February 2006. Archived from the original on 20 September 2005.

- ^ "Alternative Fueling Station Locator". U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ "Material safety data sheet" (PDF). Tesoro petroleum Companies, Inc., U.S. 8 February 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Karl Griesbaum et al. "Hydrocarbons" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_227

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Gasoline". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ E Reese and R D Kimbrough (December 1993). "Acute toxicity of gasoline and some additives". Environmental Health Perspectives. 101 (Suppl 6): 115–131. Bibcode:1993EnvHP.101S.115R. doi:10.1289/ehp.93101s6115. PMC 1520023. PMID 8020435.

- ^ University of Utah Poison Control Center (24 June 2014), Dos and Don'ts in Case of Gasoline Poisoning, University of Utah, archived from the original on 8 November 2020, retrieved 15 October 2018

- ^ Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (21 October 2014), Medical Management Guidelines for Gasoline (Mixture) CAS# 86290-81-5 and 8006-61-9, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, archived from the original on 14 November 2020, retrieved 13 December 2018

- ^ "Petrol Sniffing Fact File". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Yip, Leona; Mashhood, Ahmed; Naudé, Suné (2005). "Low IQ and Gasoline Huffing: The Perpetuation Cycle". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 1020–1021. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1020-a. PMID 15863813. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Rising Trend: Sniffing Gasoline – Huffing & Inhalants". 16 May 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Petrol Sniffing / Gasoline Sniffing". Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Benzene and Cancer Risk". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Lauwers, Bert (1 June 2011). "The Office of the Chief Coroner's Death Review of the Youth Suicides at the Pikangikum First Nation, 2006–2008". Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ "Labrador Innu kids sniffing gas again to fight boredom". CBC.ca. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Wortley, R.P. (29 August 2006). "Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Land Rights (Regulated Substances) Amendment Bill". Legislative Council (South Australia). Hansard. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ Brady, Maggie (27 April 2006). "Community Affairs Reference Committee Reference: Petrol sniffing in remote Aboriginal communities" (PDF). Official Committee Hansard (Senate). Hansard: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ^ Kozel, Nicholas; Sloboda, Zili; Mario De La Rosa, eds. (1995). Epidemiology of Inhalant Abuse: An International Perspective (PDF) (Report). National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Research Monograph 148. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Petrol-sniffing reports in Central Australia increase as kids abuse low aromatic Opal fuel". ABC News. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Williams, Jonas (March 2004). "Responding to petrol sniffing on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands: A case study". Social Justice Report 2003. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Submission to the Senate Community Affairs References Committee by BP Australia Pty Ltd" (PDF). Parliament of Australia Web Site. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Carbon Monoxide Poisoning" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Carbon monoxide poisoning - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b x-engineer.org. "Effects of vehicle pollution on human health – x-engineer.org". Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "NOx gases in diesel car fumes: Why are they so dangerous?". phys.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Human Health Risk Assessment for Gasoline Exhaust". www.canada.ca. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Facts About Gasoline". Coltura - moving beyond gasoline. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "How Gasoline Becomes CO2". Slate Magazine. 1 November 2006. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "How much carbon dioxide is produced by burning gasoline and diesel fuel?". U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Archived from the original on 27 October 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "How much carbon dioxide is produced by burning gasoline and diesel fuel?". U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Archived from the original on 27 October 2013.

- ^ V. F. Andersen; J. E. Anderson; T. J. Wallington; S. A. Mueller; O. J. Nielsen (21 May 2010). "Vapor Pressures of Alcohol−Gasoline Blends". Energy Fuels. 24 (6): 3647–3654. doi:10.1021/ef100254w.

- ^ "Water Intensity of Transportation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ University, Duke. "New models yield clearer picture of emissions' true costs". phys.org. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Shindell, Drew T. (2015). "The social cost of atmospheric release". Climatic Change. 130 (2): 313–326. Bibcode:2015ClCh..130..313S. doi:10.1007/s10584-015-1343-0. hdl:10419/85245. S2CID 41970160.

- ^ "Preventing and Detecting Underground Storage Tank (UST) Releases". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 13 October 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "Evaluation of the Carcinogenicity of Unleaded Gasoline". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010.

- ^ Mehlman, MA (1990). "Dangerous properties of petroleum-refining products: carcinogenicity of motor fuels (gasoline)". Teratogenesis, Carcinogenesis, and Mutagenesis. 10 (5): 399–408. doi:10.1002/tcm.1770100505. ISSN 2472-1727. PMID 1981951.

- ^ Baumbach, JI; Sielemann, S; Xie, Z; Schmidt, H (15 March 2003). "Detection of the gasoline components methyl tert-butyl ether, benzene, toluene, and m-xylene using ion mobility spectrometers with a radioactive and UV ionization source". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (6): 1483–90. doi:10.1021/ac020342i. PMID 12659213.

- ^ "Gasoline Sniffing". HealthyChildren.org. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "Releases or emission of CO2 per Liter of fuel (Gasoline, Diesel, LPG)". économie, écologie, énergies, innovations et société. 7 March 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Cook, John; Nuccitelli, Dana; Green, Sarah A.; Richardson, Mark; Winkler, Bärbel; Painting, Rob; Way, Robert; Jacobs, Peter; Skuce, Andrew (2013). "Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet". Environmental Research Letters. 8 (2) 024024. NASA. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8b4024C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024. S2CID 250675802. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data. Global Change Data Lab. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Fuel Consumption of Cars and Vans – Analysis". IEA. November 2021. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022.

- ^ "Gasoline, Automotive | ToxFAQs™ | ATSDR". wwwn.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Fuel Prices and New Vehicle Fuel Economy in Europe" (PDF). MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. August 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Gas Prices: Frequently Asked Questions". fueleconomy.gov. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ "Fiscal Facts". Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ "Regional gasoline price differences - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "When did the Federal Government begin collecting the gas tax?—Ask the Rambler — Highway History". FHWA. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ "New & Used Car Reviews & Ratings". Consumer Reports. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Gassing up with premium probably a waste". philly.com. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009.

- ^ Biello, David. "Fact or Fiction?: Premium Gasoline Delivers Premium Benefits to Your Car". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Why is summer fuel more expensive than winter fuel?". HowStuffWorks. 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Why Is Gas More Expensive in the Summer Than in the Winter?". HowStuffWorks. 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ "Gasoline production - Country rankings". Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Appendix B – Transportation Energy Data Book". ornl.gov. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ a b c George Thomas. "Overview of Storage Development DOE Hydrogen Program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. (99.6 KB). Livermore, California. Sandia National Laboratories. 2000.

- ^ Eyidogan, Muharrem; Ozsezen, Ahmet Necati; Canakci, Mustafa; Turkcan, Ali (2010). "Impact of alcohol–gasoline fuel blends on the performance and combustion characteristics of an SI engine". Fuel. 89 (10): 2713. Bibcode:2010Fuel...89.2713E. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2010.01.032.

- ^ "Extension Forestry" (PDF). North Carolina Cooperative Extension. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". The National Hydrogen Association. 25 November 2005. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gold, Russell. The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World (Simon & Schuster, 2014).

- Yergin, Daniel. The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (Penguin, 2011).

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (Buccaneer Books, 1994; latest edition: Reissue Press, 2008).

- Graph of inflation-corrected historic prices, 1970–2005. Highest in 2005 Archived 23 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- The Low-Down on High Octane Gasoline

- MMT-US EPA Archived 20 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- An introduction to the modern petroleum science Archived 4 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine, and to the Russian-Ukrainian theory of deep, abiotic petroleum origins.

- What's the difference between premium and regular gas? Archived 19 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine (from The Straight Dope)

- International Fuel Prices 2005 with diesel and gasoline prices of 172 countries

- EIA – Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update

- World Internet News: "Big Oil Looking for Another Government Handout", April 2006.

- Durability of various plastics: Alcohols vs. Gasoline Archived 28 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Dismissal of the Claims of a Biological Connection for Natural petroleum.

- Fuel Economy Impact Analysis of RFG Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine i.e. reformulated gasoline. Has lower heating value data, actual energy content is higher see higher heating value

- A Refiner's Viewpoint on MOTOR FUEL QUALITY Archived 4 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 'A Refiner's Viewpoint on Motor Fuel Quality' About the fuel specs refiners can control. Holaday W, and Happel J. (SAE paper 430113, 1943).

External links

[edit]- CNN/Money: Global gas prices

- EEP: European gas prices

- Transportation Energy Data Book

- Energy Supply Logistics Searchable Directory of US Terminals

- High octane fuel, leaded and LRP gasoline—article from robotpig.net

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Comparison of Regular, Midgrade, and Premium Fuel

- Images

- Down the Gasoline Trail Handy Jam Organization, 1935 (Cartoon)

Gasoline

View on GrokipediaHistory

Etymology and early nomenclature

The term "gasoline" originated in the mid-19th century as a trade name for a volatile petroleum distillate, deriving from "gas," which alluded to its ability to produce illuminating gas through evaporation or its similarity to gaseous fuels in volatility, combined with the suffix "-oline" from Latin oleum (oil) to denote an oily substance.[10] The earliest recorded variant, "gasolene," appeared in 1863 in Britain as a trademark for refined petroleum products, likely influenced by earlier brands such as "Cazeline," registered in 1862 by British merchant John Cassell for a patent illuminating oil, and its Irish imitation "Gazeline."[11] By 1864, "gasoline" had entered American usage, reflecting marketing efforts to promote the liquid as a solvent or lighter fluid distinct from gaseous "illuminating gas" (typically coal-derived town gas piped for lighting), though early nomenclature often blurred the line due to gasoline's role in generating vapors for illumination.[10] [12] In British English, the term "petrol" emerged later as a shortening of "petroleum," specifically for refined motor fuel, with roots in Medieval Latin petroleum (rock oil).[13] It was trademarked in 1892–1893 by the British firm Carless, Fitzpatrick & Co. (later Haltermann Carless) as a branded solvent and fuel, gaining prevalence in the UK and Commonwealth to differentiate automotive use from American "gasoline" amid regional patent and marketing divergences.[14] Early 19th-century nomenclature for such distillates varied widely, including "naphtha" or "benzine" for lighter fractions, but "gasoline" and "petrol" standardized as the liquid gained recognition separate from gaseous illuminants, emphasizing its petroleum origin over coal gas production.[10]Pre-industrial uses and distillation

Petroleum from natural seeps was utilized in ancient Persia and China for rudimentary applications such as lamp fuels, medicines, and incendiary mixtures, with early distillation separating lighter volatile fractions akin to naphtha for solvents and preservatives.[15] In China, petroleum extraction via drilled wells reached depths of up to 800 feet by 347 CE, primarily for fuel in salt evaporation processes, though distillation remained trial-based and focused on heavier oils.[16] By the 9th century, Persian scholar Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi documented the fractional distillation of crude oil in Kitab al-Asrar, yielding kerosene for illumination alongside lighter, more volatile distillates used medicinally or as cleaners, marking an empirical advancement in isolating hydrocarbons without theoretical purity standards.[15][17] These pre-industrial efforts emphasized kerosene-like middle distillates for practical lamps, relegating lighter gasoline-range fractions to marginal roles due to their instability and low demand. In medieval Islamic regions, alembic distillation refined seep oils for disinfectants and fuels, but light ends were often evaporated or repurposed sparingly, reflecting causal limitations in storage and combustion control.[18] The 19th-century shift to commercial refining amplified this dynamic: after Edwin Drake's 1859 well in Pennsylvania initiated systematic production, distillers prioritized kerosene for lighting, discarding or flaring the volatile light fraction—later standardized as gasoline—as a hazardous waste, though some employed it as an industrial solvent or cleaner.[19][20] Refineries like those operated by early producers treated gasoline as an "essence" byproduct, evaporating it or using it minimally due to explosion risks, with yields varying by crude source but typically comprising 10-20% of output.[9] Emerging internal combustion experiments in the 1860s-1880s began highlighting gasoline's volatility as a potential asset for liquid fuels, contrasting its prior nuisance status. Étienne Lenoir's 1860 gas engine and Nikolaus Otto's 1876 four-stroke cycle initially relied on manufactured gases, yet testers noted the evaporative properties of light petroleum distillates for carburetion prototypes, foreshadowing engine adaptations despite persistent safety concerns and preference for heavier fuels.[9][21] This recognition stemmed from empirical trials, such as vaporizing light fractions for ignition, though widespread adoption awaited automotive viability.[19]19th and early 20th century development

In the late 19th century, the invention of practical internal combustion engines transformed light petroleum distillates from mere byproducts of kerosene production into viable fuels. Karl Benz's 1885 Patent-Motorwagen, widely recognized as the first automobile, operated on ligroin—a volatile, low-boiling petroleum fraction akin to naphtha or early gasoline analogs—demonstrating the feasibility of such fuels for mobile engines despite their prior discard as waste during lamp oil refining.[22] [23] By 1896, Henry Ford's Quadricycle further advanced this application, employing straight-run gasoline derived from simple distillation, which underscored the causal link between engine design and fuel necessity amid nascent industrialization.[24] [25] Refining techniques evolved to meet burgeoning automotive needs, with continuous fractional distillation processes supplanting batch methods between 1880 and 1910, utilizing multiple interconnected stills to boost throughput and isolate gasoline fractions more efficiently from crude oil.[26] This enabled scalable production without advanced cracking, aligning supply with demand surges. The 1908 introduction of Ford's Model T accelerated this shift, as mass production of affordable vehicles—reaching over 15 million units by 1927—propelled gasoline from a niche solvent to an industrial staple, overtaking kerosene in U.S. refinery output by around 1910.[27] [28] World War I intensified gasoline's strategic role, with Allied forces consuming millions of gallons daily for trucks, aircraft, and tanks, exposing supply vulnerabilities and cementing petroleum's military primacy—Entente powers controlled over 70% of global production, averting shortages that plagued the Central Powers.[29] [30] Prewar consumption patterns, averaging 1 million gallons daily for French operations alone, escalated dramatically, driving postwar investments in refining capacity and underscoring gasoline's emergence as a cornerstone of mechanized economies devoid of contemporary octane enhancers or detergents.[31]Mass production and post-WWII advancements