Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Silverstone Circuit

View on WikipediaThis article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2022) |

Silverstone Circuit is a motor racing circuit in England, near the Northamptonshire villages of Silverstone and Whittlebury. It is the home of the British Grand Prix, which it first hosted as the 1948 British Grand Prix. The 1950 British Grand Prix at Silverstone was the first race in the newly created World Championship of Drivers. The race rotated between Silverstone, Aintree and Brands Hatch from 1955 to 1986, but settled permanently at the Silverstone track in 1987. The circuit also hosts the British round of the MotoGP series.

Key Information

Circuit

[edit]

The Silverstone circuit is on the site of a Royal Air Force bomber station, RAF Silverstone, which was operational between 1943 and 1946.[4] The station was the base for the No. 17 Operational Training Unit. The airfield's three runways, in classic WWII triangle format, lie within the outline of the present track.

The circuit straddles the Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire border and is accessed from the nearby A43. The Northamptonshire towns of Towcester (5 miles (8.0 km)) and Brackley (7 miles (11 km)) and the town of Buckingham, (situated in Buckinghamshire) (6 miles (9.7 km)) are close by, and the nearest city is Milton Keynes, the home of Formula One team Red Bull Racing. Many F1 teams have bases in the UK, but Aston Martin (formerly Force India) is the closest to the track, with a new base having just been built under a kilometre from the race circuit.

Silverstone was first used for motorsport by an ad hoc group of friends who set up an impromptu race in September 1947. One of their members, Maurice Geoghegan, lived in nearby Silverstone village and was aware that the airfield was deserted. He and eleven other drivers raced over a 2-mile (3.2 km) circuit, during the course of which Geoghegan himself ran over a sheep that had wandered onto the airfield. The sheep was killed and the car was written off, and in the aftermath of this event the informal race became known as the Mutton Grand Prix.[5]

The next year the Royal Automobile Club took a lease on the airfield and set out a more formal racing circuit. Their first two races were held on the runways themselves, with long straights separated by tight hairpin corners, the track demarcated by hay bales. However, for the 1949 International Trophy meeting, it was decided to switch to the perimeter track. This arrangement was used for the 1950 and 1951 Grands Prix. In 1952 the start line was moved from the Farm Straight to the straight linking the Woodcote and Copse corners, and this layout remained largely unaltered for the following 38 years. For the 1975 meeting a chicane was introduced to try to tame speeds through Woodcote (although motorbikes would still use the circuit without the chicane up until 1986), and Bridge corner was subtly rerouted in 1987.

The track underwent a major redesign between the 1990 and 1991 races, transforming the ultra-fast track (where, in its last years, fourth or fifth gear, depending on the transmission of the car, was used for every corner except the Bridge chicane which was usually taken in second gear) into a more technical track. The reshaped track's first Formula One race was won by Nigel Mansell in front of his home crowd. On his victory lap back to the pits Mansell picked up stranded rival Ayrton Senna to give him a lift on his side-pod after his McLaren had run out of fuel on the final lap of the race.

Following the deaths of Senna and fellow Grand Prix driver Roland Ratzenberger at Imola in 1994, many Grand Prix circuits were modified in order to reduce speed and increase driver safety. As a consequence of this the entry from Hangar Straight into Stowe was modified in 1995 to improve the run off area. In addition, the flat-out Abbey kink was modified to a chicane in just 19 days ready for the 1994 Grand Prix. Parts of the circuit, such as the starting grid, are 17 m (19 yd) wide, complying with the latest safety guidelines.[6]

History

[edit]1940s

[edit]With the termination of hostilities in Europe in 1945, the first motorsport event in the British Isles was held at Gransden Lodge in 1946 and the next on the Isle of Man, but there was nowhere permanent on the mainland which was suitable.[7]

In 1948, Royal Automobile Club (RAC), under the chairmanship of Wilfred Andrews, set its mind upon running a Grand Prix and started to cast around public roads on the mainland. There was no possibility of closing the public highway as could happen on the Isle of Man, or the Channel Islands; it was a time of austerity and there was no question of building a new circuit from scratch, so some viable alternative had to be found.[7]

A considerable number of ex-RAF airfields existed, and it was to these the RAC turned their attention to with particular interest being paid to two near the centre of England – Snitterfield near Stratford-upon-Avon and one behind the village of Silverstone. The latter was still under the control of the Air Ministry, but a lease was arranged in August 1948 and plans put into place to run the first British Grand Prix since the RAC last ran one at Brooklands in 1927 (those held at Donington Park in the late 1930s had the title of 'Donington Grand Prix').[7]

In August 1948, Andrews employed James Brown on a three-month contract to create the Grand Prix circuit in less than two months.[8] Nearly 40 years later, Brown died while still employed by the circuit.[7]

Despite possible concerns about the weather, the 1948 British Grand Prix began at Silverstone on Thursday 30 September 1948. The race took place on 2 October.[7] The new circuit was marked out with oil drums and straw bales and consisted of the perimeter road and the runways running into the centre of the airfield from two directions. Spectators were contained behind rope barriers and the officials were housed in tents. An estimated 100,000 spectators watched the race.[7]

There were no factory entries but Scuderia Ambrosiana sent two Maserati 4CLT/48s for Luigi Villoresi and Alberto Ascari who finished in that order (notwithstanding having started from the back of the grid of 25 cars) ahead of Bob Gerard in his ERA R14B/C. The race was 239 miles (385 km) long and was run at an average speed of 72.28 mph (116.32 km/h). Fourth place went to Louis Rosier's Talbot-Lago T26, followed home by Prince Bira in another Maserati 4CLT/48.[7][9]

The second Grand Prix at Silverstone was scheduled for May 1949 and was officially designated the British Grand Prix. It was to use the full perimeter track with a chicane inserted at Club. The length of the second circuit was exactly three miles and the race run over 100 laps, making it the longest post-war Grand Prix held in England. There were again 25 starters and victory went to a 'San Remo' Maserati 4CLT/48, this time in the hands of Toulo de Graffenried, from Bob Gerard in his familiar ERA and Louis Rosier in a 4½-litre Talbot-Lago. The race average speed had risen to 77.31 mph (124.42 km/h). The attendance was estimated at anything up to 120,000.[7][10]

Also in 1949, the first running took place of what was to become an institution at Silverstone, the International Trophy sponsored by the Daily Express and which become virtually a second Grand Prix. The first International Trophy was run on 20 August in two heats and a final. Victory in heat one went to Bira and the second to Giuseppe Farina – both driving Maserati 4CLT/48s, but the final went to a Ferrari Tipo 125 driven by Ascari from Farina, with Villoresi third in another Ferrari. For this meeting, the chicane at Club was dispensed with and the circuit took up a shape that was to last for 25 years.[7][11][12]

1950s

[edit]The 1950 British Grand Prix was a significant occasion for three reasons: it was the first ever World Championship Grand Prix, carrying the title of the European Grand Prix; it was the first race in the newly created World Championship of Drivers;[13][14] and the event was held in the presence of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth – the first and only time a reigning monarch has attended a motor race in Britain.[7][15]

The year was the institution of the World Championship for Driver, and Silverstone witnessed the first time that Alfa Romeo 158 'Alfettas' had been seen in England, and they took the first three places in the hands of Giuseppe Farina, Luigi Fagioli and Reg Parnell, with the race average having increased to 90.96 mph (146.39 km/h); however the race distance had been reduced to 205 miles (330 km).[7][15]

1951 was memorable for it saw the defeat of the Alfas, with victory going to José Froilán González driving the Ferrari 375. His fellow countryman Juan Manuel Fangio was second in an Alfa Romeo 159B, and Luigi Villoresi in another Ferrari 375 was third. The race distance had increased to 263 miles (423 km), and the race average speed was now 96.11 mph (154.67 km/h).[7][15]

1951 also saw the British Racing Drivers' Club (BRDC) take over the lease from the RAC, and set about making the circuit into something more permanent.[15]

The International Trophy attracted the cream of Formula One, including the seemingly invincible Alfas, driven by Fangio and Farina. However, the weather worsened for the final and visibility was almost nil, and in those conditions the Alfettas with their supercharged engines were at a distinct disadvantage. When the race was abandoned after only six laps, Parnell was in the lead in the "Thinwall Special"; no official winner was declared.[7]

In 1952, the RAC decided it no longer wished to run the circuit, and on 1 January the lease was taken on by the BRDC, with James Brown continuing as track manager. The lease covered only the perimeter track and other areas at specific times. The original pits between Abbey and Woodcote were demolished, and new pit facilities were constructed between Woodcote and Copse. Coinciding with the BRDC taking over the running of the Grand Prix, there was a little unrest within the sport which led to the downgrading of Grand Prix racing to Formula Two, which was won by Alberto Ascari at 90.9 mph (146.3 km/h) from his Ferrari teammate Piero Taruffi – both driving the Tipo 500. The podium was completed by Mike Hawthorn driving a Cooper-Bristol T12.[7]

The International Trophy was notable in 1952, in that it saw a rare victory for Hersham and Walton Motors when Lance Macklin had a win.[7]

The same situation continued into 1953 with the World Championship being run for Formula Two cars. The race was a straight fight between the Maserati and Ferrari teams, with victory going to Ascari at 92.9 mph (149.5 km/h) aboard a Ferrari Tipo 500, from the Maserati A6GCM of Fangio and another Tipo 500 of Farina. The racecard included a Formula Libre race which put the Grand Prix into perspective; Farina drove the Thinwall Special to victory at a higher speed than the actual GP, setting the first lap record at over 100 mph (160 km/h), at 100.16 mph (161.19 km/h).[7]

The 1954 Grand Prix season was the new 2.5-litre Formula One and had attracted interest from some major players. Lancia had joined the fray with their D50, and Daimler-Benz were back; the appearance of Lancia meant that there were three Italian teams competing at the highest level, the others being Ferrari and Maserati. The British were catered for by the Owen Racing Organisation with their BRMs, the Vanwall of Tony Vandervell and Connaught still competing, while Cooper-Bristol were not to be forgotten. At the start of the season, Mercedes-Benz had swept all before them, but Silverstone was a débâcle for the team, which returned to Untertürkheim in defeat. The 263 miles (423 km) race was won by Froilán González from Hawthorn in the works 625s, with Onofre Marimón third in the works Maserati 250F. The best Mercedes driver was pole-man Fangio in his W196.[7]

From 1955, the Grand Prix was alternated between Aintree and Silverstone, until 1964 when Brands Hatch took over as the alternative venue.[15]

By the time the Grand Prix returned to Silverstone in 1956, Mercedes-Benz had gone, as had Lancia as an independent entrant, the cars having been handed to Scuderia Ferrari, who ran them as 'Lancia-Ferraris'. The great Fangio scored his only British Grand Prix win in one of these cars. Second was another Lancia-Ferrari which had started the race in the hands of Alfonso de Portago, but was taken over by Peter Collins at half-distance and third place was Jean Behra in a Maserati 250F.[7]

Matters were somewhat happier for the British enthusiast at the International Trophy; a quality field had been attracted including Fangio and Collins in their Lancia-Ferraris, but the 13 laps of the race were led by the new BRM P25 driven by Hawthorn. When the engine of the BRM expired, Stirling Moss in the Vanwall took over, going on to win. With the Lancias broken by the Brit, the rest of the podium was taken by the Connaughts of Archie Scott Brown and Desmond Titterington.[7]

For 1958 drastic rule changes were introduced into Formula One, Fangio had retired and Maserati had withdrawn due to financial difficulties. Throughout the season the battle was between Ferrari and Vanwall and it was fervently hoped that Vandervell would success at home but it was not to be; the green cars fell apart, Stuart Lewis-Evans the best placed finisher in fourth. Victory went to Collins from Hawthorn, both driving Ferrari Dino 246s. The crowd of 120,000 witnessed a trio of British drivers on the podium with Roy Salvadori coming home third in one of John Cooper's Coventry-Climax rear-engined powered cars.[7]

1960s

[edit]

At the British Grand Prix of 1960, the front-engined cars were completely outclassed, the podium going to the Coventry-Climax–powered cars, with victory going to Jack Brabham in the works Cooper T53 from John Surtees and Innes Ireland in their Lotus 18s. Although the race is remembered as the race lost by Graham Hill, rather than won by Brabham. Hill stalled his BRM on the grid, left the line in last place, then proceeded to carve through the whole field. Once in the lead, the BRM was troubled by fading brakes which led to Hill spinning off at Copse.[7][16]

1961 was the year of the new 1.5 litre Formula One introduced by the governing body on safety grounds – it met with strong opposition in Britain which gave birth to the short-lived Intercontinental Formula, which extended the life of the now-obsolete Formula One cars. The International Trophy was run to this Formula and produced a notable first and last – the first and only appearance of the American Scarab and the last appearance of the Vanwall, in the hands of Surtees. The race was wet and Moss demonstrated his supreme prowess in Rob Walker's Cooper by lapping all but Brabham twice.[7]

In 1962, the second year of the Formula, the International Trophy was run for the 1.5 litre cars. This was the classic occasion when Hill in the BRM crossed the finishing line almost sideways to snatch victory from Jim Clark's Lotus 24; both drivers were credited with the same race time.[7][16]

Clark was to win the British Grand Prix when it returned to Silverstone in 1963, driving the Lotus-Climax 25. By now, even Ferrari had succumbed to the rear-engined layout, but sent only one to Northamptonshire for Surtees (Ferrari 156). He finished second, ahead of three BRM P57's of Hill, Richie Ginther and Lorenzo Bandini.[7][16]

For the 1965 season, BRM had taken a chance and signed Jackie Stewart straight from Formula Three; the International Trophy was only his fourth Formula One race, but despite this he won handsomely from Surtees in the Ferrari. When the Formula One returned for the British Grand Prix later that year, Stewart finished a creditable fifth. Fellow Scot, Clark won the race in his Lotus-Climax 33 from the BRM P261 of Hill and the Ferrari of Surtees.[7]

The following year, the new 3-litre Formula One was heralded as the Return of Power, however the first Grand Prix under these regulations was held at Brands Hatch. It was not until 1967 that the big-engined cars came to Northamptonshire. The result remained unchanged, with Clark winning in the Lotus-Cosworth 49 at a race average speed of 117.6 mph (189.3 km/h). Second was Kiwi Denny Hulme aboard the Brabham-Repco, from the Ferrari 312 of his fellow countrymen Chris Amon.[7]

There was a frightening increase in race average speed in 1969, for it rose by 10 mph (16 km/h), to 127.2 mph (204.7 km/h) when Stewart won in his Matra-Cosworth MS80 from Jacky Ickx (Brabham-Cosworth BT26) and Bruce McLaren driving one of his own Cosworth-powered M7Cs.[7]

1970s

[edit]

By 1971, the 3-litre era was now into its fifth season; it was also the year when sponsorship came to the fore. Ken Tyrrell became a constructor and Jackie Stewart won at Silverstone driving the Tyrrell 003 on his way to a second World Championship. Ronnie Peterson was second in March 711 from Emerson Fittipaldi in Lotus 72D; all were Cosworth-powered in what fast becoming Formula Super Ford; the race average was 130.5 mph (210.0 km/h).[7]

1973 was the year that Jody Scheckter lost control of his McLaren at the completion of the first lap, spinning into the pit wall and setting in motion the biggest accident ever seen on a British motor racing circuit. The race was stopped on lap two and the carnage cleared away; it speaks highly for the construction of the cars that only one driver was injured. The race was won Scheckter's teammate, Peter Revson (McLaren M23-Cosworth) from Peterson (Lotus 72E) and Denny Hulme (McLaren M23). The race average speed had risen again to 131.75 mph (212.03 km/h).[7]

The 1973 débâcle wrought changes upon Silverstone as it was deemed necessary to slow these cars through Woodcote, therefore a chicane was inserted. "Formula Super Ford" reached its peak in 1975, when 26 of the 28 entries were Cosworth-powered, there being just two Ferraris to challenge them. Tom Pryce placed his Shadow DN5 on pole for the 1975 Grand Prix, but an accident destroyed his chances as the race was run in appalling weather and it was stopped at two-thirds distance, following multiple cars crashing on the very wet circuit. Victory went to Fittipaldi (McLaren M23) from Carlos Pace (Brabham BT44B) and Scheckter (Tyrrell 007).[7]

International motor racing at Silverstone is not concerned solely to Formula One however, and 1976 saw one of the closest finishes in endurance racing during the Silverstone Six-Hour race, which was a round of the World Championship for Makes. The series was almost a German benefit that season as the main contenders were the Porsche 935s and BMW 3-litre CSLs (common known as the 'Batmobiles'). Porsche had had the upper hand in the opening rounds of the series, but at Silverstone things were different. John Fitzpatrick and Tom Walkinshaw kept their BMW ahead to win by 197 yd (180 m) (1.18secs) from the Bob Wollek/Hans Heyer Porsche 935 Turbo. Third was a Porsche 934 Turbo in the hands of Leo Kinnunen and Egon Evertz.[7]

The 1977 British Grand Prix saw the beginning of a revolution in Formula One, for towards the back of the grid was the product of Règie Renault which was exploiting a rule in F1 regulations that allowed the use of 1.5-litre turbocharged engines. The Renault RS01 expired early in the race. Ulsterman John Watson had an early battle with James Hunt, but the fuel system in Watson's Brabham-Alfa Romeo let him down and the winner Hunt (McLaren M26) won at a speed of 130.36 mph (209.79 km/h), with Niki Lauda second for Ferrari from Gunnar Nilsson in a Lotus.[7]

Once the most prestigious race of the motorcycle calendar, the Isle of Man TT had been increasingly boycotted by the top riders, and finally succumbed to pressure and was dropped, being replaced by the British Motorcycle Grand Prix. 1977 marked the beginning of this era, and Silverstone was the chosen venue. It took place on 14 August, with Pat Hennen riding a Suzuki RG500 to victory from Steve Baker (Yamaha).[17]

The International Trophy attracted World Championship contenders for the last time in 1978 but the race witnessed the début of the epoch-making Lotus 79 in the hands of Mario Andretti. Such events as this gave the Formula One also-rans a chance to start, which they were normally denied in Grands Prix; two such were the Theodore and Fittipaldi. Keke Rosberg won the former in atrocious conditions from Fittipaldi in his namesake car.[7]

14 May witnessed the running of the Silverstone Six-Hours, a round of the World Championship for Makes. A 3.2-litre Porsche 935 won in the hands of Jacky Ickx and Jochen Mass from a 3.0-litre version driven by Wollek and Henri Pescarolo; third and fourth were BMW 320s handled by Harald Grohs/Eddy Joosen and Freddy Kottulinsky/Markus Hotz. The race was run over 235 laps of the Grand Prix circuit to make a total of a little over 689 miles which the winning car covered at 114.914 mph (184.936 km/h).[7][18]

Come the 1979 Grand Prix and the passage of two years had made a great difference to the performance of the turbocharged Renaults; the car which qualified on the last row in 1977 was now on the front row beside Alan Jones in the Williams FW07. When Jones's Cosworth expired, his teammate Clay Regazzoni moved into the lead, going on to win from René Arnoux in the Renault RS10 with Jean-Pierre Jarier third in the Tyrrell 009. The winner's average speed was 138.80 mph (223.38 km/h).[7]

The 1979 British Motorcycle Grand Prix was again held at Silverstone and would be one of the closest races in the history of Motorcycle Grand Prix racing. The 1978 winner Kenny Roberts and the pair of works Suzuki riders, Barry Sheene and Wil Hartog broke away from the rest of the field. After a few laps, Hartog fell off the pace as Sheene and Roberts continued to swap the lead throughout the 28-lap event, the American winning for the second time ahead of Sheene by a narrow margin of just three-hundreds of a second.[19]

1980s

[edit]

In May 1980, sports cars returned in the form of the Silverstone Six-Hours, which was won by Alain de Cadenet driving a car bearing his own name, partnered by Desiré Wilson; the 235 laps (687 miles) being completed at 114.602 mph (184.434 km/h). The only other to complete the full race distance was the Siegfried Brunn/Jürgen Barth (Porsche 908/3), with a Porsche 935K Turbo driven by John Paul and Brian Redman third, a lap down.[7][20]

1981 saw the arrival of the one-one-one grid, staggered in two rows. The turbocharged era saw Renault occupying the front row of the grid, and turbo-engined Ferraris fourth and eighth. The Renaults dominated the race, but total reliability was still lacking and the victory went to John Watson in a McLaren MP4/1. Second place went to Carlos Reutemann in the Williams FW07C from the Talbot-Ligier JS17 of Jacques Laffite, a lap down; the race speed was down a little at 137.64 mph (221.51 km/h).[7]

For 1982, endurance sport car racing entered a rejuvenated phrase with the coming of Group C; the BRDC and l'Automobile Club de l'Ouest instituted a joint Silverstone/Le Mans Challenge Trophy. The trophy eventually went to Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell in a Porsche 956, but at Silverstone they could not make maximum use of the fuel allowance and victory went to the Lancia LC1 of Riccardo Patrese and Michele Alboreto. The winning car completed the 240 laps at a speed of 128.5 mph (206.8 km/h), with the second-place car three laps adrift, that of Ickx/Bell. The final podium place went to the Joest Racing Porsche 936C Turbo of Bob Wollek/Jean-Michel Martin/Philippe Martin.[7][21]

May 1983 saw the running of the Silverstone 1000 kilometres, which was a round of the newly instigated World Endurance Championship. Porsche dominated the event, taking the first five places, with Derek Bell and Stefan Bellof bringing their 956 home ahead of Wollek and Stefan Johansson in an identical car.[7]

In the 1983 British Grand Prix, the first Cosworth-powered car was in 13th place on the grid, all the cars ahead of it being powered by turbocharged engines. Fuel consumption of the turbos was heavy and refuelling mid-race had become necessary. With the ever-increasing power, speeds were continually on the up and in practice René Arnoux became the first person to lap the circuit in under 1:10.000 with a time of 1:09.462 in his Ferrari 126C3, a lap at over 150 mph (240 km/h). In the race, the lap record was raised to over 140 mph (230 km/h) by Frenchman Alain Prost, who won the race in the Renault RE40 at an average speed of 139.218 mph (224.050 km/h), from Nelson Piquet in the Brabham-BMW BT52B and Patrick Tambay in a Ferrari. Finishing fourth, also using Renault power, was the Lotus 94T of Nigel Mansell.[7][22]

The 1985 International Trophy, run on 24 March, was the inaugural event under the regulations for the new International Formula 3000. New Zealand driver Mike Thackwell won the International Trophy for the third time, and the first F3000 race in the process, driving a Ralt RT20 from John Nielsen in a similar car. Third place went a March 85B driven by Michel Ferté.[7]

Six weeks later, sports cars returned for the Silverstone 1000 km. Porsche cars took five of the top six placings in the shape of four 962Cs and a 956. The winners were the works pairing of Ickx/Mass from their teammates Bell and Hans-Joachim Stuck; third was the Lancia-Martini of Patrese and Alessandro Nannini.

The 1985 British Grand Prix saw Keke Rosberg in his 1,150 bhp (858 kW; 1,166 PS) Williams FW10-Honda set a qualifying lap at over 160 mph (260 km/h). Three others clocked an average lap speed of over 159 mph (256 km/h). Rosberg set his time despite a deflating rear tyre and the track still being slightly damp from earlier rain. The turbo era had reached its zenith, and while Prost put the lap record up to 150.035 mph (241.458 km/h), like most races of the era it was something of an economy run as the FIA had limited fuel capacities (220 litres per car per race). Prost went on the win in the race, in the McLaren MP4/2B, at an average of 146.246 mph (235.360 km/h) from the Ferrari 156/85 of Alboreto and the Ligier JS25 of Laffite.[7][22]

The International season opened on 13 April with the first round of the Intercontinental F3000 Championship. The first home was Pascal Fabré with a Lola T86/50 from Emanuele Pirro (March) and Nielsen (Ralt).[7]

In 1986, the Silverstone 1000 km run on 5 May was a round of the World Endurance Championship, which Silk Cut Jaguar (Tom Walkinshaw Racing) won. The Derek Warwick/Eddie Cheever XJR9 was the only car to complete the distance of 212 laps, at a speed of 129.05 mph (207.69 km/h). The Stuck/Bell Porsche 962C was two laps down in second place, with a 962C a further three laps adrift in the hands of Jo Gartner and Tiff Needell.[7]

Due to safety concerns over high speeds, by the time the Grand Prix returned in Silverstone in 1987, a new corner had been inserted before Woodcote. The first International meeting in 1987 was the initial round of the Intercontinental F3000 Championship on 12 April. The race was run at 103.96 mph (167.31 km/h), the winner being Maurício Gugelmin in a Ralt from Michel Trollé in a Lola and Roberto Moreno aboard another Ralt.[7]

In 1987, Jaguar won the Silverstone 1000 km, their fourth successive win in the World Sports Car Championship. The XJR8s took a one-two finish, with the car of Cheever and Raul Boesel winning ahead of Jan Lammers and Watson, with the Porsche 962C of Stuck and Bell third; these three crews covered the whole lap distance of 210 laps of the full GP circuit, the winning Jaguar averaging 123.42 mph (198.63 km/h).[7]

From the 1987 British Grand Prix onwards, the event was firmly established at Silverstone. The first two placings in 1987 were a repeat of the 1986 race at Brands Hatch, Mansell winning from his Williams-Honda teammate Piquet at 146.208 mph (235.299 km/h) and Ayrton Senna in the Lotus-Honda. Following a mid-race pit stop in a bid to cure a vibration in the car, Mansell found himself 29 seconds behind Piquet with 28 laps to go. He quickly cut Piquet's lead by more than a second per lap, until with five laps to go the gap was only 1.6 seconds. With two laps to go, Mansell slipstreamed Piquet down the Hangar Straight, jinked left and then dived right to pass Piquet into Stowe. To a tumultuous reception, Mansell went on to win the race.[7][22]

1987 saw the inaugural World Touring Car Championship arrive at Silverstone. Luis Pérez-Sala led the race until the penultimate lap, with a lead of nearly one minute, but then his Bigazzi-entered BMW M3 retired. He had not been sure that the car would start the race after Olivier Grouillard rolled it in practice. However, the Munich marque still took victory when the CiBiEmme Sport's M3 finished first, in the hands of Enzo Calderari and Fabio Mancini. The Schnitzer M3 of Roberto Ravaglia, Roland Ratzenberger and Pirro managed to finished second, ahead of the Alfa Romeo 75 Turbo of Giorgio Francia and Nicola Larini.[23]

The 1988 race was won at 124.142 mph (199.787 km/h), the dramatic reduction in race speed being due to heavy rain. Senna took victory in his McLaren from Mansell (Williams) and Nannini (Benetton).[7][22]

The 1988 Silverstone 1000 km saw Cheever take a hat-trick of victories for Jaguar, this time partnered by Martin Brundle. The XJR9 won at 128.02 mph (206.03 km/h) from the Sauber-Mercedes C9 driven by Jean-Louis Schlesser and Mass. The second Sauber driven by Mauro Baldi and James Weaver, was third, two laps down, while third on the road was the Porsche 962C of Bell and Needell which was disqualified for an oversize fuel tank.[7]

April 1989 saw the first round of the 1989 International F3000 Championship. Thomas Danielsson won at the wheel of a Reynard 89D, at a speed of 131.56 mph (211.73 km/h). Second by 0.5secs was Philippe Favre in a Lola T89/50 from Mark Blundell and Jean Alesi in Reynards.[7]

Mid-July is the traditional time for the British Grand Prix and on the 16th, over 90,000 spectators converged upon the circuit to see Prost score his 38th GP win in the McLaren-Honda MP4/5, at 143.694 mph (231.253 km/h). Mansell brought the Ferrari 640 into second place from Nannini's Benetton.

1990s

[edit]

The weekend of 19/20 May 1990 was a busy one at Silverstone, for on the Saturday, a round of the FIA F3000 Championship was run on the Grand Prix circuit, and on the Sunday the contenders in the World Sports-Prototype Championship had their turn. In the F3000 race, Scotland's Allan McNish led Érik Comas home from Marco Apicella. The first two were Lola T90/50 mounted, while the third-placed car was a Reynard 90D. The sports cars again ran over 300 miles, contesting the Shell BRDC Empire Trophy. The first three places went to British cars, with Jaguar first and second from a Spice-Cosworth in the hands of Fermín Vélez and Bruno Giacomelli. The winning Jaguar XJR11 of Martin Brundle and Michel Ferté was the only to run the full distance of 101 laps, lapping even the second-placed XJR11 of Jan Lammers and Andy Wallace.[7]

And so to July, and the British Grand Prix. Once again, it was over 190 miles (310 km) and was won at 145.253 mph (233.762 km/h). Alain Prost was now driving for Ferrari and his victory was rounded by Thierry Boutsen in the Williams in second, and Ayrton Senna's McLaren in third.[7]

After the Grand Prix, it had already been decided to extensively redesign Silverstone's layout. Nearly every part of Silverstone (except Copse, Abbey and all of the straights, save the Farm Straight) was redesigned. The ultra-high speed Club and Stowe corners were made slower and a chicane was placed before Club. Maggotts, Becketts and Chapel were re-designed as very fast snaky esses that proved to be even more challenging than the original series of corners – the considerable amount of lateral acceleration change from side to side became the highlighted challenge of the new circuit. A new twisty infield section called Luffield was created in place of the Farm Straight and the Bridge chicane. Despite these alterations, the Grand Prix and World Sportscar circuses both very much approved of the new layout: Silverstone was still fast, which is what it has always been known for.

When the Group C cars returned in 1991, they raced for the World Sports Car Championship, but the race distance was reduced to 269 miles (433 km) (83 laps of the GP circuit) and it was a straight battle between Jaguar and Mercedes-Benz, with victory going to the Jaguar XJR14 of Teo Fabi and Derek Warwick at a speed of 122.048 mph (196.417 km/h). In second place, four laps behind, came the Mercedes C291 of Michael Schumacher and Karl Wendlinger, followed by the singleton driver XJR14 of Brundle.[7]

July came, and with it came, of course, the Grand Prix. The almost unbelievably popular victory was Nigel Mansell's 18th Grand Prix win, making him the most successful British driver ever. Only two other drivers completed the full race distance: Gerhard Berger for McLaren and Prost for Ferrari.[7]

1992 was once more a very busy International season for Silverstone with a round of the International F3000 Championship, the World Sports Car Championship, and of course, the Grand Prix. The first two were run on the same day, 10 May. Although the practice was spoilt by hailstorm, the races were run in bright weather. The F3000 victor was Jordi Gené who completed the 37 laps at a speed of 121.145 mph (194.964 km/h) in a Reynard-Mugen 92D, from a similar Judd-engined example in the hands of Rubens Barrichello. Lola-Cosworth were third and fourth, driven by Olivier Panis and Emanuele Naspetti.[7]

1992 was also notable for the title decider for the British Touring Car Championship which involved an incident between Tim Harvey and John Cleland, during which Cleland gave a middle finger to Harvey's BMW teammate Steve Soper, prompting Murray Walker to exclaim "'I'm going for first,' says John Cleland!" A few corners later, Soper and Cleland both crashed out, gifting the title to Harvey. This is widely viewed as one of the most iconic moments in BTCC history.[24]

The sports car race was a sad affair, with but a handful of cars coming to the grid. There were 11 starters and just five finishers. The race was won by the Peugeot 905 of Warwick and Yannick Dalmas at 122.661 mph (197.404 km/h), two laps ahead of the Maurizio Sandro Sala/Johnny Herbert Mazda MXR-01 which was four laps ahead of the Lola-Judd T92/10 driven by Jésus Pareja and Stefan Johansson. At the end of the season, the World Sports Car Championship was no more.[7]

The Grand Prix was a happier affair with Williams-Renaults of Mansell and Riccardo Patrese taking top honours from the Benettons of Brundle and Schumacher. Mansell dominated practice and the race, winning at 133.772 mph (215.285 km/h).[7]

Six days after competing at Donington Park, the F3000 guys were at Silverstone for the second round of the 1993 International F3000 Championship. Gil de Ferran won at 119.462 mph (192.255 km/h) from David Coulthard and Michael Bartels – all were driving Cosworth powered Reynard 93Ds.[7]

Despite back-to-back Grand Prix victories for Williams, Mansell would not be back in 1993 to try for a famous hat-trick as he was racing in the States. However, things looked good for his replacement, Damon Hill after he set the fastest time in practice, but Prost (now at Williams) pipped him to pole by just 0.128secs and he went on to win the race after Hill's engine exploded 18 laps from home. Second and third were the Benettons of Schumacher and Patrese.[7][25]

A year later, the Grand Prix was a race of controversy which rumbled on for most of the season: Hill was barely ahead of Schumacher on the grid and on the formation lap the young German sprinted ahead of him, which was not allowed under the rules (cars were required to maintain station during the formation lap). The race authorities informed Benetton that their man had been penalised 5 seconds for his transgression but they did not realise that it was a stop/go penalty and did not call Schumacher in, so he was black-flagged. Schumacher ignored the black flag for six laps, and for failing to respond to the black flag Schumacher was disqualified, having finished second on the road. Hill won the race from Jean Alesi in the Ferrari and Mika Häkkinen in the McLaren.[7]

The 1994 F3000 race was an all Reynard 94D affair. The 38-lap race was won by Franck Lagorce winning at 119.512 mph (192.336 km/h), from Coulthard and de Ferran. The race distance for the following season had increased by two. Victorious on this occasion was Riccardo Rosset driving Super Nova's Reynard-Cosworth AC 95D. His teammate Vincenzo Sospiri finished second, while Allan McNish was third in a Zytek-Judd KV-engined 95D.[7]

Hill and Schumacher were not having a happy 1995 and managed to take each other off after the final pit stops, leaving Coulthard in the lead which he lost when he had to take a 10 sec 'stop/go' penalty for speeding in the pit lane. All of this left Herbert to take his maiden Grand Prix win – he was euphoric and was held shoulder high on the podium by the second and third-placed men, Coulthard and Alesi.[7]

On 12 May 1996, the Northamptonshire circuit hosted a round of the International BPR series which was very a British affair. First was the McLaren F1 GTR of Andy Wallace and Olivier Grouillard followed by the Jan Lammers/Perry McCarthy Lotus Esprit and another McLaren in the hands of James Weaver and Ray Bellm.[7]

At the Grand Prix on 14 July, Damon Hill qualified first. He spun out of contention when a front wheel nut became loose, and his teammate Jacques Villeneuve went on to win at a fraction over 124 mph (200 km/h), from Berger's Benetton and the McLaren of Häkkinen.[7]

The 1997 Grand Prix was again won by Villeneuve at the wheel of a Williams-Renault at a speed of 128.443 mph (206.709 km/h) from the Benettons of Alesi and Alexander Wurz.[7]

From the start of 1998, the FIA decreed that all Formula One grids must be straight: in order to comply with this, the RAC moved the start line forward at Silverstone but not, significantly, the finish line. This led to some confusion at the end of the Grand Prix, which was scheduled for 60 laps, but was effectively 59.95 laps. With the timing being taken from the finish line and not the start line, the winning car was in the pits at the end of the race and the Ferrari pit was situated between the two lines. The chequered flag is supposed to be waved at the winning car and then showed to the other competitors, but it was waved at the second man who thought that he had won.[7]

Victory went to Schumacher at the wheel of a Ferrari in appalling conditions. In addition to pit lane confusion, he was penalised 10 seconds for passing another racer under a yellow flag. The stewards failed to inform the teams of their decision in the proper manner so Schumacher took his stop go penalty in the pits, after the race was over. McLaren appealed to the FIA, but the appeal was rejected and the results were confirmed, with Häkkinen second in the McLaren and Eddie Irvine third in the second Ferrari.[7]

Victory in the 1999 British Grand Prix went to Coulthard's McLaren-Mercedes with an average speed of 124.256 mph (199.971 km/h).[7]

2000s

[edit]For Silverstone's first Grand Prix of the 21st Century, the FIA decreed that the race should be moved to April, and the event took place over Easter, with the GP itself run on Easter Sunday. In hindsight this was a poor decision by the FIA, who failed to take into account the unpredictable weather in Britain at this time of year. It rained almost continually for the best part of three weeks before the event and most of Good Friday; by Easter Saturday the car parks had virtually collapsed and were completely closed. Although most of the race day itself was fine, the damage was done and many thousands of spectators were unable to get to Silverstone to witness David Coulthard win his second straight victory in the event, from his McLaren teammate Mika Häkkinen, with Michael Schumacher third for Ferrari.[7][26]

On 14 May, the FIA GT Championship came to Northants, in slightly more clement conditions and victory went to Julian Bailey and Jamie Campbell-Walter driving a Lister Storm GT from no fewer than four Chrysler Viper GTS-Rs.[7]

The 2000 Silverstone 500 USA Challenge was the first American Le Mans Series race to be held outside of North America. It served as a precursor to the creation of the European Le Mans Series by gauging the willingness of European teams from the FIA Sportscar Championship and FIA GT Championship to participate in a series identical to the American Le Mans Series. This event also shared the weekend at Silverstone with an FIA GT round, with some GT teams running both events. The race was won by the Schnitzer Motorsport's BMW V12 LMP of Jörg Müller and JJ Lehto.[27]

Formula One returned for the 2001 British Grand Prix in July to see Häkkinen triumph having managing to overtake the driver in pole, Schumacher. Schumacher, driving for Ferrari finished second while teammate Barrichello gained the final spot in the podium.[28]

The 2002 British Grand Prix saw Ferrari return to the top two steps of the podium with Schumacher beating Barrichello, while pole-sitter and Williams driver Juan Pablo Montoya finished in third. These three drivers, as well as gaining the top three qualifying places, were the only drivers to finish on the lead lap. This year marked the first year of British Grand Prix being promoted by American sports agency Octagon pursuant to lease agreement with BRDC signed in December 2000.[29] Octagon also assumed the management of the circuit and acquired the assets and liabilities of Silverstone Circuits Limited from BRDC. BRDC kept the ownership of the circuit.

Although the 2003 Grand Prix was won by pole-sitter Barrichello for Ferrari, the race is probably most remembered for a track invasion by the defrocked priest, Neil Horan, who ran along Hangar Straight, head-on to the 175 mph (282 km/h) train of cars, wearing a saffron kilt and waving religious banners. Kimi Räikkönen (McLaren) was pressured by Barrichello into losing the lead and an unforced error later on allowed Montoya to seize second.[30]

Neil Hodgson had a brilliant World Superbike meeting in 2003. The Fila Ducati rider withstood the attention of James Toseland in the first race and then fellow Ducati pilot, Gregorio Lavilla in the second, just 0.493secs ahead of the Spaniard. Rubén Xaus claimed two third-place finishes.[31]

On 30 September 2004, British Racing Drivers' Club president Jackie Stewart announced that the British Grand Prix would not be included on the 2005 provisional race calendar and, if it were, would probably not occur at Silverstone.[32] However, on 9 December an agreement was reached with former Formula One rights holder Bernie Ecclestone ensuring that the track would host the British Grand Prix until 2009 after which Donington Park would become the new host. However, the Donington Park leaseholders, Donington Ventures Leisure, ran into severe financial problems and went into administration, resulting in the BRDC signing a 17-year deal with Ecclestone to hold the British Grand Prix at Silverstone.[33] In an unrelated case, due to financial problems affecting parent company The Interpublic Group of Companies, Octagon terminated its lease of Silverstone Circuit and ceased promoting British Grand Prix after 2004. BRDC reassumed the management of the circuit and acquired assets and liabilities of Octagon subsidiary Silverstone Motorsport Limited and merged them back into reactivated Silverstone Circuits Limited, this reverted the 2000 transaction.[34][35]

Schumacher celebrated his 80th Grand Prix victory of his career at the 2004 event after taking the lead from Räikkönen during the first round of pit stops. Barrichello completed the podium in third, and coming home in fourth was BAR's Jenson Button.[36]

A crowd of 68,000 saw Renegade Ducati's Noriyuki Haga and Ten Kate Honda's Chris Vermeulen take a win each in the 2004 World Superbike event. Haga pulled off a close finish in race one, just beating Vermeulen. In race two, the roles were reversed with the Honda beating the Ducati.[37]

When the Le Mans Prototypes returned in 2004, they raced for the Le Mans Series over a distance of 1000 km. It was a straight battle between the pair of Audi R8's of Audi Sport UK Team Veloqx and Team Goh's singleton R8, with victory going to the Veloqx pair of Allan McNish and Pierre Kaffer. In second place, one lap behind was Rinaldo Capello and Seiji Ara for Team Goh, followed by the all British pair of Johnny Herbert and Jamie Davies for Veloqx.[38]

A crowd of 27,000 welcomed back the World Touring Car Championship. The Alfa Romeo drivers dominated the first race, on a sunny 15 May 2005. Gabriele Tarquini scored a lights to flag victory, leading home an Alfa quartet. Behind the Italian, a tough fight for second between James Thompson and Fabrizio Giovanardi, with a number of overtaking and paint swapping moves, also involving the BMW 320i of Andy Priaulx. Augusto Farfus completed the quartet, with Priaulx dropping back to fifth.[39] After a superb start, Priaulx led most of race two, until side-lined with a puncture. This enabled the SEAT duo of Rickard Rydell and Jason Plato to take the win for the Spanish manufacturer, with Tarquini in third.[40]

Ducati took both legs of the 2005 World Superbike double-header. Régis Laconi scored the first win and Toseland doubled Ducati's pleasure. Laconi beat Troy Corser to the finishing line by 0.096secs. Toseland claimed third on the podium. Toseland turn came to Race 2, when he passed Croser and Haga.[41]

Montoya won the 2005 British Grand Prix.[42]

In the 2005 Le Mans Series race, Team ORECA Audi R8 scored a prestigious victory, with McNish, this time paired with Stéphane Ortelli, winning after a thrilling race-long battle with the Creation Autosportif's DBA 03S of Nicolas Minassian and Campbell-Walter, a car that provided much of the season's excitement.[38]

Alonso would see the chequered flag first as he wins again at Silverstone in 2006. In doing so, the Spaniard became the youngest driver to get the hat-trick (pole position, winning and fastest lap). Alonso won by nearly 14 seconds from Schumacher and Räikkönen took third again.[43]

Troy Bayliss gained a pair of wins in the 2006 World Superbike, aboard his Xerox Ducati. Haga (Yamaha) and Toseland (Honda) joined Bayliss on the podium in both races.[44]

Following Hamilton's victory in the 2007 Canadian Grand Prix, Silverstone reported that ticket sales had "gone through the roof"; circuit director Ian Phillips added, "we haven't seen this level of interest since Mansell-mania in the late 80s and early 90s". Hamilton qualified his McLaren on pole. However, race day saw Räikkönen move ahead during the first round of pit stops. The other McLaren driver, Alonso, finished second.[45][46]

Bayliss (Ducati) took the chequered flag in a solitary 2007 World Superbike race, with a heavy downpour causing the first race to be run in the wet, with Race 2 cancelled altogether. Naga and Corser completed the podium line-up.[47]

After a one-year hiatus, the Le Mans Series returned to Silverstone. At the head of the field, the Team Peugeot 908 HDi's lead was unchallenged and Minassian achieved his goal to do one better, partnered by Marc Gené. Emmanuel Collard/Jean-Christophe Boullion finished two laps down in second. Third place on the podium was for the Rollcentre Pescarolo, piloted by Stuart Hall and Joao Barbosa.[48]

Hamilton won the 2008 British Grand Prix, when he crossed the line to win by 68 seconds. The margin of victory was the largest in Formula One since 1995. Once again, Barrichello finished on the podium, this time in a Honda.

A spirited drive from the 2008 Le Mans winners Rinaldo Capello and McNish saw their Audi R10 TDI progress through the field after a trip in the gravel early in the race, all the way up to second behind their sister car. When the leading Audi came in for an unplanned pit stop and was pulled into the pit for some rear suspension repairs, this handed the lead to McNish and Capello, who took a well deserved win. The Charouz Lola-Aston Martin B08/60 was second, driven by Jan Charouz and Stefan Mücke. The Pescarolo of Romain Dumas and Boullion got a well deserved podium finish.[49]

The 2009 British Grand Prix at Silverstone was due to be the last in Northamptonshire, as the event was moving to Donington Park from the 2010 season. The race was won by Sebastian Vettel for Red Bull Racing, 15.1secs ahead of his teammate Mark Webber. A further 25.9secs behind was Barrichello, in his Brawn. However, due to Donington Park funding issues, the Grand Prix would remain at Silverstone.[50]

The 2009 1000 km of Silverstone saw Oreca take the chequered flag with the aid of their drivers Olivier Panis and Nicolas Lapierre. The next three cars home were also on the lead lap after 195 laps of racing, with second place going to Speedy Racing's Lola-Aston Martin B08/60 of Marcel Fässler, Andrea Belicchi and Nicolas Prost. The newer Lola-Aston Martin B09/60 of Aston Martin Racing took the next two places, with the partnership of Tomáš Enge, Charouz and Mücke claiming the final step on the podium.[51]

2010s

[edit]

Mark Webber (Red Bull) won the 2010 British Grand Prix, just over a second ahead of McLaren's Hamilton. Nico Rosberg claimed third place for Mercedes.[52]

The FIM World Superbike Championship round at Silverstone in 2010 was dominated by British riders. In both races, Yamaha Sterilgarda's Cal Crutchlow won with Jonathan Rea second. Alstare Suzuki's Leon Haslam and Aprilla's Leon Camier made appearances in the top three, giving Britain a complete podium sweep of the event.[53]

The 2010 British motorcycle Grand Prix returned to Silverstone for the first time since 1986, although the category had evolved into MotoGP. Jorge Lorenzo dominated the event for Fiat Yamaha, finishing nearly seven seconds clear of a battle for second place. Andrea Dovizioso won the battle for second for Repsol Honda, with the Tech 3 Yamaha of Ben Spies third, after passing fellow American Nicky Hayden on the last lap.[54]

Anthony Davidson and Minassian won for Peugeot in the 2010 1000 km of Silverstone. Second place was enough for the Oreca team to be crowned as the 2010 champions, using a Peugeot instead their own race winning chassis from the 2009 event. This time Lapierre was co-driven by Stéphane Sarrazin. Audi were third with the R15 TDI of Capello and Timo Bernhard.[55]

The 2011 British Grand Prix saw Fernando Alonso win for Ferrari, sixteen seconds ahead of the Red Bulls of Vettel and Webber.[56]

The Althea Racing Ducati of Carlos Checa won ahead of Yamaha's Eugene Laverty with Laverty's teammate Marco Melandri finishing third in both races of the 2011 World Superbike meeting.[57]

MotoGP returned in June 2011, with the Repsol Hondas dominating the race in rainy conditions. Casey Stoner took pole position and beat his teammate Dovizioso by more than 15 seconds. The Tech 3 Yamaha of Colin Edwards completed the podium.[58]

The 2011 6 Hours of Silverstone witnessed a nose-to-tail fight between the Audi R18 of Bernhard and Fässler and the Peugeot 908 of Sébastien Bourdais and Simon Pagenaud, but was temporarily finished after a spin by Bernhard. A conservative drive from Pagenaud saw him caught and then overtaken by Fässler. Pagenaud picked up the pace and the two cars were on each other's tails until the end of the fourth hour when damaged rear bodywork needed replacing on the Audi. This gave the Peugeot a one-minute advantage that it did not give up. Third was the OAK Racing's Pescarolo 01 piloted by Olivier Pla and Alexandre Prémat.[59]

The 2012 British Grand Prix was won for the second time by Webber, with pole-sitter Alonso second for Ferrari, finishing three seconds behind. Webber's teammate Vettel rounded off the podium.[60]

Silverstone is often the site of unpredictable weather, and the 2012 World Superbike event took place in mixed wet and dry conditions. Kawasaki Racing's Loris Baz won from the BMWs of Michel Fabrizio and Ayrton Badovini. Baz then took second behind PATA Racing's Ducati, piloted by Sylvain Guintoli in a shortened second race. Jakub Smrz took third, as nine riders went down before the official called an early end after eight laps.[61]

The 2012 British MotoGP was won by the Yamaha factory rider, Lorenzo. He crossed the line 3.313 seconds ahead of the Respol Honda of Stoner, with Dani Pedrosa third on the other Honda.[62]

The 2012 Le Mans 24 Hours winners Benoît Tréluyer, André Lotterer and Fässler steered their Audi R18 e-tron Quattro hybrid car to victory in the 6 Hours of Silverstone on 26 August 2012. The second Audi of Allan McNish, Rinaldo Capello and Tom Kristensen, finished third, with the Toyota TS030 hybrid of Alex Wurz, Kazuki Nakajima and Nicolas Lapierre splitting the two in second, having led early on.[63]

The opening round of the 2013 World Endurance Championship saw Audi Sport Team Joest dominating. The race soon developed into a pattern of two Audi R18 e-tron quattros followed by two Toyota TS030 Hybrids and backed up by two Rebellion Lola B12/60s. Audis had a better early stage of the race when the Toyota's tyres did not work well, and by the middle of the race they were securely leading the race by one lap. McNish was behind Tréluyer by more than 20 seconds with some 15 laps to go. But McNish (partnered by Kristensen and Loïc Duval), and motivated to win the RAC Tourist Trophy award for the race, closed the gap and overtook Tréluyer (supported by Lotterer and Fässler) two laps before the finish. The podium was completed the Toyota of Davidson/Sarrazin/Sébastien Buemi.[64]

Mercedes's Rosberg held off Red Bull's Webber to win the 2013 British Grand Prix. In a race featuring two safety car interventions and tyre failures on five cars (four of which blew the rear-right tyre), Ferrari's Alonso finished third from ninth on the grid. Rosberg's teammate, Hamilton, dropped to last with tyre failure, but recovered to finish fourth ahead of Lotus's Räikkönen.[65]

Pata Honda's Jonathan Rea took advantage of the fluctuating weather conditions to take the lead mid-distance during the 2013 World Superbike Race 1, which he held until the end. Aprilia Racing's Eugene Laverty followed home for second place, with Crescent Suzuki's Leon Camier third. Race 2 started dry but deteriorated to treacherously damp by mid-race. This saw Baz prevailing, replicating his victory from 2012, in similar conditions. Jules Cluzel took his Crescent Suzuki up to second place, followed home by Laverty in third.[66]

Reigning World MotoGP Champion, Lorenzo, ended Marc Márquez's four-race winning streak to take victory in the 2013 British MotoGP. Yamaha factory-rider, Lorenzo swapped the lead three times with Márquez through the last few corners, but Lorenzo managed to make the crucial pass and win. Márquez's Repsol Honda teammate, Pedrosa finished third, while Crutchlow was seventh. Meanwhile, in the supporting Moto2 race, Scott Redding won.[67][68]

Easter Sunday 2014 saw the return of Porsche to top-level sportscar racing in the World Endurance Championship event. Toyota dominated the event, as the Toyota TS040 Hybrid of Sébastien Buemi, Anthony Davidson and Nicolas Lapierre took victory by a clear lap over their teammates, Alex Wurz, Kazuki Nakajima and Stéphane Sarrazin, at the end of a race that was red-flagged before its scheduled finish courtesy of heavy rain. Porsche claimed a podium on its return with the 919 Hybrid. The partnership of Mark Webber, Timo Bernhard and Brendon Hartley took third, finishing two laps down on the winner and one down on the second-placed Toyota.[69]

Mercedes driver Lewis Hamilton won the 2014 British Grand Prix. He was catching his teammate and championship rival, Nico Rosberg, at the half-way stage of the race when Rosberg suffered a gearbox failure and was forced to retire, with Williams's Valtteri Bottas coming from 14th on the grid to finish second. Red Bull's Daniel Ricciardo took third. The race had to be red flagged following a high-speed crash on the opening lap of Kimi Räikkönen.[70]

The reigning world champion Marc Márquez won the Hertz British MotoGP for his 11th win in 12 starts. The Honda rider overtook the previous year's winner Jorge Lorenzo on a Yamaha with three laps to go to cross the line 0.732 seconds in front. The second works Yamaha of Valentino Rossi completed the podium, after fending off Honda's Dani Pedrosa.[71]

The escalating costs of the British Grand Prix led to the BRDC triggering a break clause in their contract, meaning that the 2019 British Grand Prix would be the last at the Silverstone Circuit. Although there was speculation of a street race in London, lengthy negotiations with Liberty Media led to a new agreement for Silverstone to continue to host the British Grand Prix for a further five years after 2019.[72]

World Champion Lewis Hamilton's win at the 2019 British Grand Prix was his sixth win at the Silverstone circuit, and with it, he broke a 52-year-old record for most wins in the British Grand Prix by a Formula One driver. The previous record of five wins was set and held by Jim Clark in 1967. This record was then matched by Alain Prost in 1993, and Hamilton in 2017.[73]

2020s

[edit]The 2020 British motorcycle Grand Prix, scheduled to be held at Silverstone, was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Silverstone Circuit held two Formula One World Championship races in one season in 2020 (behind closed doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic) on consecutive weekends with the races on 2 and 9 August; the second race was referred to as the 70th Anniversary Grand Prix to commemorate the 70 years since the inception of the Formula One World Championship in 1950.[74]

In December 2020 the BRDC named the pit straight after Lewis Hamilton in recognition of his achievements.[75] This is the first time in the circuit's history that an area of the track has been named after an individual.[76]

Leading up to the Sunday race of the 2022 British motorcycle Grand Prix, it was confirmed that the 2023 race would start on the Hamilton Straight, with Abbey becoming the new turn 1, which is the same configuration as in F1.[77] This was the first time that the MotoGP, 2 and 3 class started at the Hamilton straight since the 2012 event.[citation needed]

In February 2024, Silverstone and Formula One agreed a ten-year contract extension to host the British Grand Prix, with the new deal lasting until the 2034 event.[78]

Before the Moto3 race in 2024, the 2025 dates were confirmed to be 23–25 May 2025, this would be the earliest a British motorcycle Grand Prix has ever been hosted in Silverstone and its former track Donington Park.[79][80]

In the Moto2 Race, British rider Jake Dixon won his first home race in his career, making him the first British rider to win his home race since Danny Kent won the 2015 Moto3 race.[81]

After 945 days without a victory in Formula 1, Lewis Hamilton won his ninth British Grand Prix breaking the record for most wins at a single circuit or Grand Prix and extending his consecutive Silverstone podium record to 12.[82][83]

On 6 July 2025, Google commemorated the 75th anniversary of Formula 1 and its origination at Silverstone in 1950 with a dedicated Google Doodle on their homepage, showcasing the iconic Silverstone track, Wing building and red car with the number 75 emblazoned upon it. Lando Norris won his first British Grand Prix becoming the 13th British driver to win on home soil.[83][84]

Other competitions

[edit]

Silverstone also hosts many club racing series and the world's largest historic race meeting, the Silverstone Classic. It was also host to a 24-hour car race, the Britcar 24, having run between 2005 and 2018.

It has in the past hosted exhibition rounds of the D1 Grand Prix both in 2005 and 2006. The course, starting from the main straight used in club races, makes use of both Brooklands and Luffield corners to form an S-bend – a requirement in drifting – and is regarded by its judge, Keiichi Tsuchiya, as one of the most technical drifting courses of all.[85] The section, used in drifting events since 2002, is currently used to host a European Drift Championship round. The Course also hosts the Formula Student Competition by the iMechE yearly.

In 2010 Silverstone hosted its very first Superleague Formula event.[86]

Events

[edit]- Current events

- 22 February: Pomeroy Trophy

- 15–16 March: BRSCC Season Opener

- 5–6 April: Britcar

- 25–27 April: British GT Championship Silverstone 500, GB3 Championship, GB4 Championship

- 2–4 May: Britcar BRSCC Silverstone 24 Hours, Supercar Challenge, F4 British Championship

- 17–18 May: TCR UK Touring Car Championship

- 23–25 May: Grand Prix motorcycle racing British motorcycle Grand Prix, British Talent Cup

- 4–6 July: Formula One British Grand Prix, FIA Formula 2 Championship Silverstone Formula 2 round, FIA Formula 3 Championship

- 2–3 August: GB3 Championship, GB4 Championship, GT Cup Championship

- 22–24 August: Silverstone Classic

- 5–7 September: Ferrari Challenge UK Ferrari Racing Days

- 12–14 September: European Le Mans Series 4 Hours of Silverstone, Le Mans Cup, Ligier European Series

- 20–21 September: British Touring Car Championship, F4 British Championship, Porsche Carrera Cup Great Britain

- 27–28 September: BRSCC Silverstone Finals Race Weekend

- 11–12 October: HSCC Finals

- 19–20 October: MRL Silverstone GP Meeting

- 1–2 November: Walter Hayes Trophy

- Future events

- Eurocup-3 (2026)

- F1 Academy (2026)

- Former events

- 24H Series (2016, 2018)

- Alpine Elf Europa Cup (2018–2019)

- American Le Mans Series

- Auto GP (2006, 2013, 2015)

- BMW M1 Procar Championship (1979)

- BPR Global GT Series (1995–1996)

- British Formula 3 International Series (1971–2014)

- British Formula Two Championship (1989–1994, 1996)

- British Superbike Championship (1998–2023)

- British Supersport Championship (1998–2023)

- EuroBOSS Series (1995–1999, 2001, 2003–2004)

- Eurocup Mégane Trophy (2008–2011)

- Euroformula Open Championship (2013–2019)

- European Formula 5000 Championship (1969–1975)

- European Formula Two Championship (1967, 1975, 1977, 1979–1984)

- European Touring Car Championship (1970, 1972–1986, 1988, 2001–2002)

- European Truck Racing Cup (1985–1988)

- F4 Eurocup 1.6 (2010)

- Ferrari Challenge Europe (2006–2007, 2012, 2014, 2017–2018, 2022)

- Ferrari Challenge Italia (2008)

- FIA European Formula 3 Championship (1980–1984)

- FIA European Formula 3 Cup (1987)

- FIA Formula 3 European Championship (2013–2015, 2017–2018)

- FIA GT Championship (1997–2002, 2005–2009)

- FIA GT1 World Championship

- RAC Tourist Trophy (2010–2011)

- FIA GT3 European Championship (2006–2011)

- FIA World Endurance Championship

- 4 Hours of Silverstone (2019)

- 6 Hours of Silverstone (2012–2018)

- FIA World Rallycross Championship

- World RX of Great Britain (2018–2019)

- FIM Endurance World Championship (1983, 2002)

- Formula 3 Euro Series (2011)

- Formula 750 (1973–1976)

- Formula BMW Europe (2008–2010)

- Formula One

- 70th Anniversary Grand Prix (2020)

- Formula Palmer Audi (1998–2000, 2002–2005, 2007–2010)

- Formula Renault 2.0 Northern European Cup (2013–2016)

- Formula Renault Eurocup (1995–1996, 1998–1999, 2001–2002, 2008–2011, 2015, 2017–2019)

- Grand Prix Masters (2006)

- GT World Challenge Europe (2013–2019)

- GT4 European Series (2007–2011, 2013, 2016)

- GP2 Series

- Silverstone GP2 round (2005–2016)

- GP3 Series (2010–2018)

- International Formula 3000

- BRDC International Trophy (1985–1990, 1992–2004)

- International GT Open (2013–2019)

- JK Racing Asia Series (2012)

- Lamborghini Super Trofeo Europe (2009, 2011–2019)

- International Touring Car Championship (1996)

- MotoE World Championship

- British eRace (2023)

- Porsche Supercup (1994–2020, 2022–2024)

- Red Bull MotoGP Rookies Cup (2011–2015)

- Renault Sport Trophy (2015)

- SEAT León Eurocup (2014–2016)

- Sidecar World Championship (1977–1984, 1986, 2002–2003)

- Silverstone 24 Hour (2005–2013, 2015–2018)

- Superbike World Championship (2002–2007, 2010–2013)

- Superleague Formula (2010)

- Supersport World Championship (2002–2007, 2010–2013)

- Trofeo Maserati (2003–2006, 2014)

- USAC Cup National Championship (1978)

- World Series Formula V8 3.5 (2008–2012, 2015–2017)

- World Sportscar Championship (1976–1988, 1990–1992)

- World Touring Car Championship

- FIA WTCC Race of UK (1987, 2005)

- W Series (2021–2022)

Lap records

[edit]

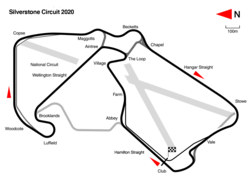

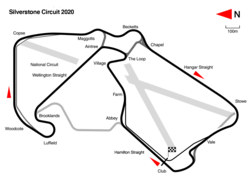

Max Verstappen's lap of 1:27.097 in the 2020 British Grand Prix is the official race lap record for the current Grand Prix configuration, which has only been in existence since 2011. The diagram at right illustrates the changes in configuration which have been made, a detailed description of the changes which have been made, see development history of Silverstone Circuit.

Official lap records are set in a race, although qualifying laps are typically faster. The fastest lap of 1:24.303 was set by Lewis Hamilton during 2020 qualification.[87] As of September 2025, the fastest official race lap records of Silverstone are listed as:

Fatalities

[edit]- Harry Schell – 1960 BRDC International Trophy[255]

- Bob Anderson – 1967 British Grand Prix[256]

- Martin Brain – Nottingham Sports Car Club meeting[257]

- Graham Coaker – Formula Libre[258]

- Norman Brown – 1983 British motorcycle Grand Prix[259]

- Peter Huber – 1983 British motorcycle Grand Prix

- Darren Needham – Mini Challenge UK[260]

- Denis Welch – 2014 Jack Brabham Memorial Trophy[261]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "List Of FIA Licensed Circuits Updated On : 2025-11-03" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 3 November 2025. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ "British GP". FIA.com. Federation Internationale de l'Automobile. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "New Silverstone circuit gets green light for 2010 British Grand Prix". Silverstone Circuit. British Racing Drivers' Club. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "Silverstone – UK Airfield Guide". www.ukairfieldguide.net. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Tibballs, Geoff (2001). Motor Racing's Strangest Races. London: Robson Books. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-86105-411-1.

- ^ Moskvitch, Katia (25 February 2011). "Formula 1 seeks to be better by design". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br Peter Swinger, Motor Racing Circuits in England : Then & Now (Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0 7110 3104 5, 2008)

- ^ Jones, Matt (2 July 2014). "The history of Silverstone circuit". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "British Grand Prix • STATS F1". Statsf1.com. 2 October 1948. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "II British Grand Prix • STATS F1". Statsf1.com. 14 May 1949. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone". Silverstone.co.uk. 2 October 1948. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "BRDC International Trophy • STATS F1". Statsf1.com. 20 August 1949. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Mike Lang, Grand Prix! Volume 1, 1950 to 1965, p. 14

- ^ World Championship of Drivers, 1974 FIA Yearbook, Grey section, pp. 118–119

- ^ a b c d e "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone – The 1950s". Silverstone.co.uk. 27 August 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone – The 1960s". Silverstone.co.uk. 27 August 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Chris Carter, "Motocourse 1977–1979" (Hazleton Securities Ltd, ISBN 0 905138-04-X, 1979)

- ^ "Silverstone 6 Hours 1978 – Race Results". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "· Silverstone 1979 – a Roberts-Sheene classic". Motogp.com. 13 January 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Silverstone 6 Hours 1980 – Race Results". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Silverstone 6 Hours 1982 – Race Results". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone – The 1980s". Silverstone.co.uk. 5 September 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "1987 WTC – round 7". Touringcarracing.net. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ BTCC Silverstone 1992 Round 15, 15 March 2015, retrieved 12 July 2023

- ^ "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone – The 1990s". Silverstone.co.uk. 5 September 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "The History of British Motorsport and Motor Racing at Silverstone – The 2000s". Silverstone.co.uk. 5 September 2009. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Silverstone 500, USA Challenge May 13, 2000 Official results" (PDF). European Le Mans Series. 13 May 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Hakkinen halts Schumacher charge". BBC. 15 July 2001. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Brands Hatch Leisure Limited Directors' Report and Financial Statements - Year Ended 31 December 2000 from Companies House

- ^ Legard, Jonathan (20 July 2003). "A very British curse". BBC Sport. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2003 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "British GP set for axe". Itv-f1.com. 1 October 2004. Archived from the original on 24 March 2005. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Silverstone seals British GP deal". BBC News. 9 December 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Engels 1 Limited Directors' Report and Financial Statements - Year Ended 31 December 2004 from Companies House

- ^ Silverstone Circuits Limited Directors' Report and Financial Statements - For The Year Ended 30 June 2005 from Companies House

- ^ "Schumacher takes 80th career win at British GP". Motorsport.com. 13 July 2004. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "2004 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b "European Le Mans Series". European Le Mans Series. 9 May 2004. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "WTCC: Race results (1) – Silverstone. – WTCC Results – May 2005". Crash.net. 15 May 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "WTCC: Race results (2) – Silverstone. – WTCC Results – May 2005". Crash.net. 15 May 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2004 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "British GP – Sunday – Race Report – Monty Casino!". Grandprix.com. 11 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Alonso cruises to first British win". Formula 1. 11 June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "2006 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2007 FORMULA 1 Santander British Grand Prix". Formula 1. 8 July 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Hamilton win triggers ticket rush – F1 news". Autosport.com. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "2007 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2007 Le Mans Series Silverstone 1000 km – Report and Slideshow". Ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "2008 Le Mans Series Silverstone 1000 km – Report and Slideshow". Ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (21 June 2009). "BBC SPORT | Motorsport | Formula 1 | Vettel romps to Silverstone win". BBC News. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2009 Le Mans Series Silverstone 1000 km – Report and Slideshow". Ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (11 July 2010). "BBC Sport – F1 – British Grand Prix: Webber storms to British GP win". BBC News. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2010 WSB Silverstone Results". Motorcycle USA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "AirAsia British Grand Prix". Motogp.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2010 Le Mans Series Silverstone 1000 km (ILMC) – Report and Slideshow". Ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (10 July 2011). "BBC Sport – British Grand Prix: Fernando Alonso storms to Silverstone win". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Silverstone World Superbike Results 2011". Motorcycle USA. 31 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "· AirAsia British Grand Prix". Motogp.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "2011 Le Mans Series 6 Hours of Silverstone (ILMC) – Report and Slideshow". Ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Mark Webber charges to superb British Grand Prix victory – F1 news". Autosport.com. 8 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "World Superbike Silverstone Results 2012". Motorcycle USA. 5 August 2012. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "· Hertz British Grand Prix". Motogp.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Audi wins 6 Hours of Silverstone to claim WEC Manufacturer title | Michelin UK Motorsport". Motorsport.michelin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "News". Racing Sports Cars. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (30 June 2013). "BBC Sport – British GP: Nico Rosberg wins after Lewis Hamilton Pirelli blowout". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "World Superbike Silverstone Results 2013 – Motorcycle USA". motorcycle-usa.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Silverstone MotoGP: Jorge Lorenzo beats Marc Marquez in epic race". Autosport. 1 September 2013.

- ^ "British GP: Jorge Lorenzo edges Marc Marquez for win". Bbc.co.uk. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Watkins, Gary. "Silverstone WEC: Toyota starts 2014 with one-two, disaster for Audi". autosport.com. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Lewis Hamilton wins classic British GP after Nico Rosberg retires". Bbc.co.uk. 6 July 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "GP Results – 2014 British Grand Prix MotoGP RAC Classification". motogp.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "F1 announce British GP at Silverstone is saved with new five-year deal | British Grand Prix". The Guardian. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ FOM/SNTV, Source (14 July 2019). "Lewis Hamilton wins a record sixth British Grand Prix – video". The Guardian.

- ^ "F1 confirms first 8 races of revised 2020 calendar, starting with Austria double header". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (12 December 2020). "Silverstone names pit straight after Hamilton". BBC Sport. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Silverstone renames International Pits Straight in recognition of Lewis Hamilton's outstanding achievements". Silverstone. 12 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ MotoGP™🏁 [@MotoGP] (7 August 2022). "The provisional dates for the 2023 #BritishGP are in! 🗓️ And we're heading back to the International Paddock! ✅ #MotoGP | 📰 https://t.co/WVUfXE7Fb1" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Silverstone confirmed as host of the Formula 1 British Grand Prix until 2034". Silverstone Circuit. 8 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "👋 @SilverstoneUK, see you again in May 2025! Next year's #BritishGP 🇬🇧 dates are out! 📅". X (formerly Twitter). 4 August 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "MotoGP Will Kick Off Silverstone's Trifecta of Major Events in 2025". Silverstone. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "MotoGP British GP: Full Moto2 and Moto3 results – Ivan Ortola picks up the Moto3 victory while Jake Dixon triumphs in Moto2 at the British Grand Prix". autosport.com. 4 August 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "2024 F1 British Grand Prix results: Hamilton takes record-breaking ninth Silverstone win". Silverstone. 7 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2025.

- ^ a b Kelly, Sean (6 July 2025). "Best facts and stats from the British Grand Prix". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 7 July 2025.

- ^ "Norris wins dramatic British GP as Hulkenberg takes P3". www.formula1.com. 6 July 2025. Retrieved 7 November 2025.

- ^ JDM Option Volume 29 – 2006 D1GP Silverstone UK

- ^ "12 races on the 2010 Superleague Formula by Sonangol schedule / News archive / News & Media / Home". Superleague Formula. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Formula 1 Pirelli British Grand Prix 2020 - Qualifying". Formula One World Championship Limited. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2025.

- ^ a b "FIA WEC - 2019 4 Hours of Silverstone - Final Classification" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). 1 September 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "2015 Formula Renault 3.5 Series - Silverstone - Race 2 (40' +1 lap) - Final Classification" (PDF). 6 September 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "2025 European Le Mans Series - Goodyear 4 Hours of Silverstone – Race - Final Classification" (PDF). 14 September 2025. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "2013 Silverstone Auto GP". Motor Sport Magazine. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2021.