Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Batucada.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Batucada

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Batucada

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Batucada is a dynamic percussive style within samba, originating in Brazil, that features ensemble performances by a group of drummers called a bateria, emphasizing complex, syncopated rhythms played on traditional percussion instruments such as the surdo, tamborim, and cuíca.[1] This style is renowned for its call-and-response structure and communal energy, serving as the rhythmic backbone of Rio de Janeiro's carnival parades and samba school rehearsals.[2]

The origins of batucada trace back to the late 1920s in Rio de Janeiro's Estácio neighborhood, where it was pioneered by the Deixa Falar samba school, founded in 1928, as a structured evolution of earlier Afro-Brazilian forms like samba de roda, maxixe, and capoeira.[3] It gained prominence during the 1929 carnival and spread through influential schools like Portela, becoming standardized in samba recordings and performances by the 1930s and 1940s, reflecting a blend of African rhythmic traditions—particularly from Angolan influences—and European elements.[2] Key figures, including conductors like Oscar Bigode and Alcebíades Barcelos (inventor of the surdo around 1927), shaped its development, emphasizing harmonic tuning and rhythmic precision over improvisation.[3]

In performance, batucada is led by a mestre de bateria who directs the ensemble through composed patterns categorized as marca (steady beats), cortar (divisions), ripica (syncopated African-derived rhythms), and floriados (ornamented variations), often tuned in harmonic intervals like seconds and thirds for tonal cohesion.[3] Essential instruments include the deep bass surdo for marking the pulse, the high-pitched repique for calls, friction cuíca for vocal-like effects, frame pandeiro for accents, and shaker-like ganzá and reco-reco for texture, all contributing to the style's infectious balanço (swing).[1] Today, batucada symbolizes Brazil's Afro-Brazilian heritage and national identity, performed globally in cultural festivals while preserving its roots in resistance and community celebration.[2]

This pattern repeats, with the second measure often shortened for response cues. Harmonic rhythm emerges subtly through fluctuations in percussion density, where swells and layered accents imply underlying chord progressions, blending Afro-Brazilian pulse with European harmonic sensibilities despite the percussion-only format.[19][2]

History

Origins in Early 20th-Century Brazil

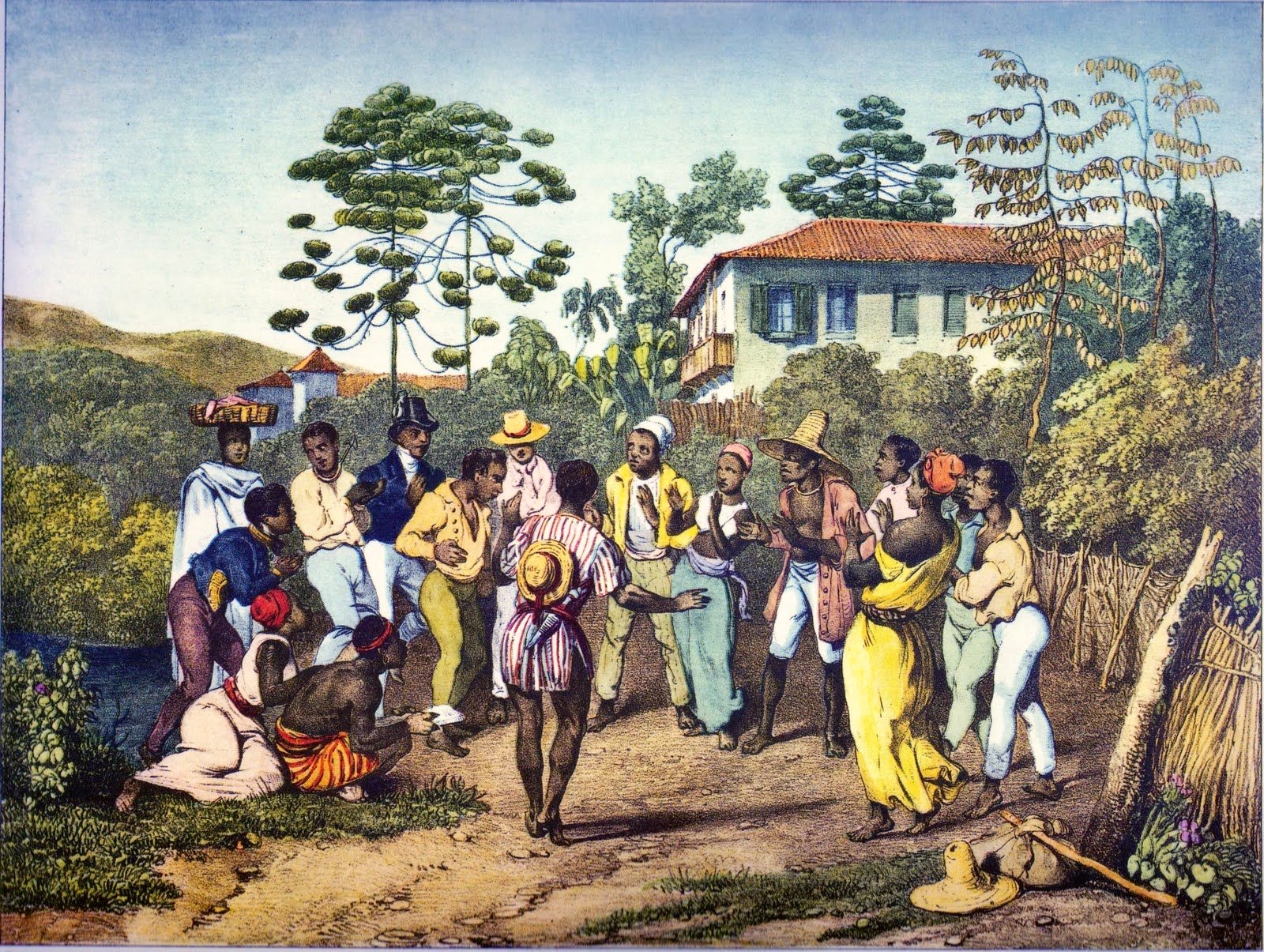

Batucada emerged as a percussive ensemble style in the early 20th century, characterized by intense, polyrhythmic drumming derived from Afro-Brazilian traditions, particularly the rhythms of candomblé religious ceremonies.[4] These influences stemmed from the cultural practices of enslaved Africans brought to Brazil during the colonial period, where Bantu and Sudanic rhythmic patterns were adapted using locally available materials to create instruments like drums and shakers.[4] By the 1920s, batucada began to crystallize in Rio de Janeiro's urban landscape as a communal form of expression, blending these African elements with European harmonic structures from genres like maxixe and choro.[5] The tradition took shape through informal carnival groups known as blocos carnavalescos, which formed in Rio's working-class neighborhoods and favelas starting around 1917.[5] These early blocos evolved from rudimentary percussion using household items like pots and pans during street processions, gradually organizing into more structured drumming ensembles by the late 1920s.[4] A pivotal moment came in 1928 with the establishment of the first samba schools, such as Deixa Falar in the Estácio neighborhood, where batucada was formalized as a core component of carnival parades.[5] Portuguese colonial rhythms, including march-like beats, intermingled with African slave contributions to shape batucada's syncopated style, as seen in early samba compositions that incorporated percussive elements.[5] Pioneering figures like Ismael Silva, a key composer from the Estácio de Sá group, played a crucial role by integrating batucada rhythms into sambas such as those recorded in the late 1920s, emphasizing heavier percussion to evoke urban vitality.[5] Amid Brazil's rapid urbanization in the early 20th century, batucada rose among working-class communities in Rio's favelas as a means of cultural resistance and social bonding, countering marginalization faced by Afro-Brazilian populations during economic shifts and rural-to-urban migration.[5] These ensembles provided a platform for collective identity in the face of socioeconomic exclusion, transforming informal street gatherings into symbols of resilience by the 1930s.[4]Integration into Samba Schools and Carnival

The first official samba school, Deixa Falar, was established on August 12, 1928, in the Estácio de Sá neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro by Ismael Silva, Bide, Armando Marçal, Nilton Bastos, and others, transforming informal carnival blocks into organized groups that adopted batucada as the core percussion ensemble for their parades to enhance rhythmic drive and communal participation.[5] Precursors like Portela, founded in 1923, and Estação Primeira de Mangueira, founded in 1928, also quickly integrated batucada sections featuring surdo drums and other percussion to structure their processions, setting a model for subsequent schools.[5] These early adoptions formalized batucada's role, shifting from spontaneous street rhythms to disciplined parade accompaniments that unified singers, dancers, and instrumentalists.[6] A pivotal milestone occurred in 1932 when the Brazilian government regulated Carnival celebrations, organizing the first official competitive parade of samba schools at Praça Onze in Rio de Janeiro, where nineteen groups showcased their batucada-driven performances, effectively mandating structured percussion sections as essential to the format.[6] This regulation elevated samba schools from marginal community associations to sanctioned cultural institutions, with batucada ensembles required to synchronize with enredo themes and choreography during the event.[5] By the mid-1930s, under President Getúlio Vargas, samba schools received official recognition in 1935, permitting their downtown parades and embedding batucada as a symbol of national unity.[5] Vargas' cultural policies from the 1930s onward promoted samba, including its batucada elements, as a cornerstone of Brazilian national identity, using state radio like Rádio Nacional to broadcast percussion-heavy recordings that celebrated racial mixture while monitoring content to suppress overtly political or dissenting Afro-Brazilian expressions.[5] This approach romanticized batucada's Afro-Brazilian roots in songs like "Aquarela do Brasil" (1939), positioning it as an emblem of harmonious mestiçagem, though it curtailed some unfiltered candomblé-influenced rituals to align with authoritarian control.[7] Through these policies, batucada evolved from a favela practice to a state-endorsed spectacle, influencing school repertoires to emphasize patriotic themes during Carnival.[8] From the 1940s to the 1960s, samba school batucada ensembles expanded significantly in scale and complexity, growing from around 20 percussionists in the early years to over 100 members by the postwar period, enabling more intricate polyrhythms and visual synchronization in parades.[9] Competitions intensified, with innovations like the 1950s introduction of samba-enredo—narrative sambas tailored to parade themes—further centering batucada as the rhythmic backbone.[6] By the 1970s, standardized bateria sizes of 200-300 musicians were established through league regulations, professionalizing roles such as mestre de bateria and ensuring consistent power for the Sambódromo-era spectacles.[9]Instruments and Ensemble

Core Percussion Instruments

The core percussion instruments of batucada form the rhythmic foundation of this Brazilian ensemble style, primarily consisting of drums and bells derived from Afro-Brazilian traditions adapted in early 20th-century Rio de Janeiro. These instruments, including the surdo, repique, tamborim, cuíca, and agogô, are typically constructed from wood or metal shells with animal skin or synthetic heads, evolving from rudimentary homemade versions using butter barrels and nailed leathers to professional models with tunable hardware by the mid-20th century.[3] Their acoustic properties emphasize layered tones, from deep bass resonances to high-pitched calls, enabling the dense polyrhythms characteristic of batucada.[5] The surdo, or bass drum, serves as the heartbeat of the ensemble and traces its origins to African ngoma drums brought by enslaved people and adapted in 1920s Rio samba schools, with its invention credited to Alcebíades Barcelos around 1927 for the Deixa Falar group. It features a single-headed construction with a wooden or metal body and leather or synthetic skin head, typically measuring 20–24 inches in diameter and 18–24 inches in height, allowing for tunable pitches via metal rods or keys. Variations include the surdo primeiro (first, largest at 24 inches for the lowest tone), segundo (second, mid-range), and terceiro (third, smallest at around 20 inches for higher bass), producing a deep, resonant boom with warm sustain from leather heads lasting about two seconds.[3][10][3] The repique, a high-pitched drum related to but distinct from the surdo, was incorporated into samba percussion in the 1930s, becoming established by the 1950s in Rio samba schools. Constructed similarly with a single head on a wooden or metal shell and tunable synthetic or leather skin, it is smaller, typically 10–14 inches in diameter, enabling clear, singing tones higher than those of the surdos. Its acoustic profile offers a sharp, dense resonance suited for melodic variation, with modern models featuring metal tuning hardware for precise pitch control.[3] The tamborim, a small frame drum of Afro-Portuguese origin integrated into samba by the late 1920s, is handheld with a single synthetic or animal skin head stretched over a wooden or metal frame, usually 5–8 inches in diameter and 2 inches deep. Historically, early versions used cat skins, as noted in 1950s Portela practices, evolving to durable nylon heads post-World War II for consistent performance. It produces a sharp, high-pitched crack with minimal tonal sustain, often tuned to D or G for harmonic balance within the ensemble.[3][5][3] The cuíca, a friction drum of African Bantu roots introduced to popular samba by Deixa Falar in the 1920s, consists of a wooden or metal body with a single animal skin head connected internally to a bamboo stick rubbed with a damp cloth to vary tension. Sizes vary from portable 12-inch models to larger versions, with heads tuned to pitches like G# or C# for undulating tones spanning up to a minor tenth. Its distinctive squeaky, vocal-like glissandi mimic human cries, achieved through friction that creates long, open sounds resembling "a/u" vowels.[3][5][3] The agogô, a double-bell instrument of Yoruba African origin adopted in Brazilian percussion by the early 20th century, is forged from welded steel or aluminum sheets, typically measuring 14–15 inches long with two conjoined bells of differing sizes for contrasting pitches. Early homemade versions used recycled metal, transitioning to chromed or lacquered professional models by the 1950s to prevent rust and enhance durability. It yields a bright, penetrating clang with the larger bell providing a lower tone and the smaller a higher one, cutting through dense ensembles.[11][12] The pandeiro, a hand-held tambourine-like instrument of Portuguese and African origin, features a single-headed frame with jingles (platinelas), typically 10–12 inches in diameter, used in batucada for rhythmic accents and fills since the early days of samba schools. It is played by shaking, striking the head with hand or mallet, and muffling, producing versatile tones from crisp jingles to muffled thumps. The caixa, or snare drum, adapted from military traditions, provides sharp backbeats and rolls in batucada ensembles, with a wooden or metal shell, double-headed with snares, usually 12–14 inches in diameter. Introduced to samba in the 1930s, it adds crisp, cutting accents to the rhythmic layers. The reco-reco, a scraped percussion idiophone of African origin, consists of a metal or bamboo tube or serrated surface scraped with a stick, producing rasping textures that enhance syncopation in batucada. Adopted in the early 20th century, it provides continuous rhythmic drive. The chocalho, or ganzá, a shaker made of metal sheets with beads or pebbles, delivers high-frequency sibilance and swing, typically 8–12 inches tall, integrated into samba for textural support from the 1920s onward.Ensemble Organization and Roles

A batucada ensemble, known as a bateria in the context of samba schools, typically comprises 50 to 300 or more percussionists, depending on the group's scale and affiliation with Carnival parades. These members are organized into distinct sections based on instrument function, ensuring rhythmic layering and cohesion. The marcação section, anchored by surdo drums, forms the foundational pulse, with surdo de primeira providing the primary downbeat, surdo de segunda handling call-and-response patterns, and surdo de terceira introducing variations. Leading and sustaining elements come from the conduction section, including repique drums for melodic cues and fills, caixa (snare drums) for sharp accents and rolls, and tamborim for intricate high-pitched rhythms. Supporting textures are added by the acompanhamento section, featuring instruments like cuíca for vocal-like effects, reco-reco for scraped rhythms, agogô bells, chocalho shakers, and pandeiro tambourines for melodic fills.[13] Leadership of the bateria is provided by the mestre de bateria, the conductor who directs the ensemble through hand signals, whistles, and repique calls to maintain tempo, dynamics, and synchronized breaks known as paradinhas. The mestre oversees the overall sound balance and cues transitions, drawing on deep knowledge of all instruments to guide the group without disrupting the flow. Additional roles include support staff such as roadies, who handle instrument transport, maintenance, and setup during parades and rehearsals, ensuring logistical efficiency for large-scale performances. Musicians within sections specialize in their instruments, with surdo players emphasizing steady foundation, repique performers leading variations, caixa drummers delivering accents, and pandeiro players adding improvisational fills.[13][14] Rehearsals for batucada ensembles occur weekly in community centers called quadras, beginning several months before Carnival—often as early as July—and intensifying through sectional practices and full-group sessions to build synchronization and physical stamina. These sessions focus on rhythmic precision and endurance, preparing performers for parades lasting 60 to 90 minutes, where the bateria must sustain high energy amid marching. Technical rehearsals in venues like the Sambadrome follow, allowing final adjustments to timing and formations.[15][16] Batucada has traditionally been male-dominated, with women historically sidelined from percussion roles in baterias due to sexist attitudes and cultural stereotypes associating drumming with masculinity. Since the 1980s, following Brazil's return to democracy and rising feminist movements, female participation has increased, including in all-female groups formed in the 2010s that challenge gender norms by featuring women as drummers, composers, and leaders. Specific roles continue to evolve, with more women now playing surdo, caixa, and repique, though all-female ensembles remain a minority amid ongoing efforts to promote inclusivity.[17][18]Rhythms and Musical Structure

Fundamental Rhythmic Patterns

Batucada's fundamental rhythmic patterns revolve around polyrhythmic structures that interlock to create a driving, syncopated groove, typically in 2/4 time with a binary feel emphasizing duple subdivisions. The core rhythm is anchored by the surdo, which delivers a steady quarter-note pulse acting as the ensemble's heartbeat, often notated as a low "boom" on the downbeat (beat 1) and a higher "chick" on beat 2, with variations introducing rests or accents for call-and-response dynamics. This binary pattern provides stability while allowing higher instruments to weave syncopated fills around it.[19][20] Interlocking layers build complexity on this foundation: the surdo maintains quarter-note pulses, while the tamborim introduces eighth-note syncopations that cross and fill the gaps, such as patterns accenting the "&" of beats for a propulsive swing. The cuíca contributes sliding glissandi and vocal-like accents to punctuate transitions, enhancing the polyrhythmic texture without overpowering the base. In standard samba de batucada grooves, these elements coalesce at tempos of 120-160 BPM, fostering an energetic forward motion suitable for carnival processions.[19][2][21] A simple notational example for the surdo in a 4/4 adaptation (common for transcription) illustrates this base:| boom - chick | boom - |

| 1 & 2 | 3 & 4 |

| boom - chick | boom - |

| 1 & 2 | 3 & 4 |