Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bayer filter

View on Wikipedia

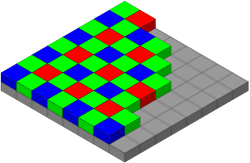

A Bayer filter mosaic is a color filter array (CFA) for arranging RGB color filters on a square grid of photosensors. Its particular arrangement of color filters is used in most single-chip digital image sensors used in digital cameras, and camcorders to create a color image. The filter pattern is half green, one quarter red and one quarter blue, hence is also called BGGR, RGBG,[1][2] GRBG,[3] or RGGB.[4]

It is named after its inventor, Bryce Bayer of Eastman Kodak. Bayer is also known for his recursively defined matrix used in ordered dithering.

Alternatives to the Bayer filter include both various modifications of colors and arrangement and completely different technologies, such as color co-site sampling, the Foveon X3 sensor, the dichroic mirrors or a transparent diffractive-filter array.[5]

Explanation

[edit]

- Original scene

- Output of a 120×80-pixel sensor with a Bayer filter

- Output color-coded with Bayer filter colors

- Reconstructed image after interpolating missing color information

- Full RGB version at 120×80-pixels for comparison (e.g. as a film scan, Foveon or pixel shift image might appear)

Bryce Bayer's patent (U.S. Patent No. 3,971,065[6]) in 1976 called the green photosensors luminance-sensitive elements and the red and blue ones chrominance-sensitive elements. He used twice as many green elements as red or blue to mimic the physiology of the human eye. The luminance perception of the human retina uses M and L cone cells combined, during daylight vision, which are most sensitive to green light. These elements are referred to as sensor elements, sensels, pixel sensors, or simply pixels; sample values sensed by them, after interpolation, become image pixels. At the time Bayer registered his patent, he also proposed to use a cyan-magenta-yellow combination, that is another set of opposite colors. This arrangement was impractical at the time because the necessary dyes did not exist, but is used in some new digital cameras. The big advantage of the new CMY dyes is that they have an improved light absorption characteristic; that is, their quantum efficiency is higher.

The raw output of Bayer-filter cameras is referred to as a Bayer pattern image. Since each pixel is filtered to record only one of three colors, the data from each pixel cannot fully specify each of the red, green, and blue values on its own. To obtain a full-color image, various demosaicing algorithms can be used to interpolate a set of complete red, green, and blue values for each pixel. These algorithms make use of the surrounding pixels of the corresponding colors to estimate the values for a particular pixel.

Different algorithms requiring various amounts of computing power result in varying-quality final images. This can be done in-camera, producing a JPEG or TIFF image, or outside the camera using the raw data directly from the sensor. Since the processing power of the camera processor is limited, many photographers prefer to do these operations manually on a personal computer. The cheaper the camera, the fewer opportunities to influence these functions. In professional cameras, image correction functions are completely absent, or they can be turned off. Recording in Raw-format provides the ability to manually select demosaicing algorithm and control the transformation parameters, which is used not only in consumer photography but also in solving various technical and photometric problems.[7]

Demosaicing

[edit]Demosaicing can be performed in different ways. Simple methods interpolate the color value of the pixels of the same color in the neighborhood. For example, once the chip has been exposed to an image, each pixel can be read. A pixel with a green filter provides an exact measurement of the green component. The red and blue components for this pixel are obtained from the neighbors. For a green pixel, two red neighbors can be interpolated to yield the red value, also two blue pixels can be interpolated to yield the blue value.

This simple approach works well in areas with constant color or smooth gradients, but it can cause artifacts such as color bleeding in areas where there are abrupt changes in color or brightness especially noticeable along sharp edges in the image. Because of this, other demosaicing methods attempt to identify high-contrast edges and only interpolate along these edges, but not across them.

Other algorithms are based on the assumption that the color of an area in the image is relatively constant even under changing light conditions, so that the color channels are highly correlated with each other. Therefore, the green channel is interpolated at first then the red and afterwards the blue channel, so that the color ratio red-green respective blue-green are constant. There are other methods that make different assumptions about the image content and starting from this attempt to calculate the missing color values.

Artifacts

[edit]Images with small-scale detail close to the resolution limit of the digital sensor can be a problem to the demosaicing algorithm, producing a result which does not look like the model. The most frequent artifact is Moiré, which may appear as repeating patterns, color artifacts or pixels arranged in an unrealistic maze-like pattern.

False color artifact

[edit]A common and unfortunate artifact of Color Filter Array (CFA) interpolation or demosaicing is what is known and seen as false coloring. Typically this artifact manifests itself along edges, where abrupt or unnatural shifts in color occur as a result of misinterpolating across, rather than along, an edge. Various methods exist for preventing and removing this false coloring. Smooth hue transition interpolation is used during the demosaicing to prevent false colors from manifesting themselves in the final image. However, there are other algorithms that can remove false colors after demosaicing. These have the benefit of removing false coloring artifacts from the image while using a more robust demosaicing algorithm for interpolating the red and blue color planes.

Zippering artifact

[edit]The zippering artifact is another side effect of CFA demosaicing, which also occurs primarily along edges, is known as the zipper effect. Simply put, zippering is another name for edge blurring that occurs in an on/off pattern along an edge. This effect occurs when the demosaicing algorithm averages pixel values over an edge, especially in the red and blue planes, resulting in its characteristic blur. As mentioned before, the best methods for preventing this effect are the various algorithms which interpolate along, rather than across image edges. Pattern recognition interpolation, adaptive color plane interpolation, and directionally weighted interpolation all attempt to prevent zippering by interpolating along edges detected in the image.

However, even with a theoretically perfect sensor that could capture and distinguish all colors at each photosite, Moiré and other artifacts could still appear. This is an unavoidable consequence of any system that samples an otherwise continuous signal at discrete intervals or locations. For this reason, most photographic digital sensors incorporate something called an optical low-pass filter (OLPF) or an anti-aliasing (AA) filter. This is typically a thin layer directly in front of the sensor, and works by effectively blurring any potentially problematic details that are finer than the resolution of the sensor.

Modifications

[edit]This section may contain material unrelated to the topic of the article and should be moved to color filter array instead. (September 2012) |

The Bayer filter is almost universal on consumer digital cameras. Alternatives include the CYGM filter (cyan, yellow, green, magenta) and RGBE filter (red, green, blue, emerald), which require similar demosaicing. The Foveon X3 sensor (which layers red, green, and blue sensors vertically rather than using a mosaic) and arrangements of three separate CCDs (one for each color) doesn't need demosaicing.

Panchromatic cells

[edit]

On June 14, 2007, Eastman Kodak announced an alternative to the Bayer filter: a colour-filter pattern that increases the sensitivity to light of the image sensor in a digital camera by using some panchromatic cells that are sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light and collect a larger amount of light striking the sensor.[8] They present several patterns, but none with a repeating unit as small as the Bayer pattern's 2×2 unit.

Another 2007 U.S. patent filing, by Edward T. Chang, claims a sensor where "the color filter has a pattern comprising 2×2 blocks of pixels composed of one red, one blue, one green and one transparent pixel," in a configuration intended to include infrared sensitivity for higher overall sensitivity.[9] The Kodak patent filing was earlier.[10]

Such cells have previously been used in "CMYW" (cyan, magenta, yellow, and white)[11] "RGBW" (red, green, blue, white)[12] sensors, but Kodak has not compared the new filter pattern to them yet.

Fujifilm "EXR" color filter array

[edit]

Fujifilm's EXR color filter array are manufactured in both CCD (SuperCCD) and CMOS (BSI CMOS). As with the SuperCCD, the filter itself is rotated 45 degrees. Unlike conventional Bayer filter designs, there are always two adjacent photosites detecting the same color. The main reason for this type of array is to contribute to pixel "binning", where two adjacent photosites can be merged, making the sensor itself more "sensitive" to light. Another reason is for the sensor to record two different exposures, which is then merged to produce an image with greater dynamic range. The underlying circuitry has two read-out channels that take their information from alternate rows of the sensor. The result is that it can act like two interleaved sensors, with different exposure times for each half of the photosites. Half of the photosites can be intentionally underexposed so that they fully capture the brighter areas of the scene. This retained highlight information can then be blended in with the output from the other half of the sensor that is recording a 'full' exposure, again making use of the close spacing of similarly colored photosites.

Fujifilm "X-Trans" filter

[edit]

The Fujifilm X-Trans CMOS sensor used in many Fujifilm X-series cameras is claimed[13] to provide better resistance to color moiré than the Bayer filter, and as such they can be made without an anti-aliasing filter. This in turn allows cameras using the sensor to achieve a higher resolution with the same megapixel count. Also, the new design is claimed to reduce the incidence of false colors, by having red, blue and green pixels in each line. The arrangement of these pixels is also said to provide grain more like film.

One of main drawbacks for custom patterns is that they may lack full support in third party raw processing software like Adobe Photoshop Lightroom[14] where adding improvements took multiple years.[15]

Quad Bayer

[edit]Sony introduced Quad Bayer color filter array, which first featured in the iPhone 6's front camera released in 2014. Quad Bayer is similar to Bayer filter, however adjacent 2×2 pixels are the same color, the 4×4 pattern features 4× blue, 4× red, and 8× green.[16] For darker scenes, signal processing can combine data from each 2×2 group, essentially like a larger pixel. For brighter scenes, signal processing can convert the Quad Bayer into a conventional Bayer filter to achieve higher resolution.[17] The pixels in Quad Bayer can be operated in long-time integration and short-time integration to achieve single shot HDR, reducing blending issues.[18] Quad Bayer is also known as Tetracell by Samsung, 4-cell by OmniVision,[17][19] and Quad CFA (QCFA) by Qualcomm.[20]

On March 26, 2019, the Huawei P30 series were announced featuring RYYB Quad Bayer, with the 4×4 pattern featuring 4× blue, 4× red, and 8× yellow.[21]

Nonacell

[edit]On February 12, 2020, the Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra was announced featuring Nonacell CFA. Nonacell CFA is similar to Bayer filter, however adjacent 3×3 pixels are the same color, the 6×6 pattern features 9× blue, 9× red, and 18× green.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]

- US patent 3971065, Bryce E. Bayer, "Color imaging array", issued 1976-07-20 on web

Notes

[edit]- ^ Jeff Mather (2008). "Adding L* to RGBG". Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ dpreview.com (2000). "Sony announce 3 new digital cameras". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21.

- ^ Margaret Brown (2004). Advanced Digital Photography. Media Publishing. ISBN 0-9581888-5-8.

- ^ Thomas Maschke (2004). Digitale Kameratechnik: Technik digitaler Kameras in Theorie und Praxis. Springer. ISBN 3-540-40243-8. Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ^ Wang, Peng; Menon, Rajesh (29 October 2015). "Ultra-high-sensitivity color imaging via a transparent diffractive-filter array and computational optics". Optica. 2 (11): 933. Bibcode:2015Optic...2..933W. doi:10.1364/optica.2.000933.

- ^ "Patent US3971065 - Color imaging array - Google Patents". Archived from the original on 2013-08-11. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ^ Cheremkhin, P. A., Lesnichii, V. V. & Petrov, N. V. (2014). "Use of spectral characteristics of DSLR cameras with Bayer filter sensors". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 536 (1) 012021. Bibcode:2014JPhCS.536a2021C. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/536/1/012021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John Compton and John Hamilton (2007-06-14). "Color Filter Array 2.0". A Thousand Nerds: A Kodak blog. Archived from the original on 2007-07-20. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ "US patent publication 20070145273 "High-sensitivity infrared color camera"". Archived from the original on 2017-02-22.

- ^ "US Patent Application 20070024879 "Processing color and panchromatic pixels"". Archived from the original on 2016-12-21.

- ^ L. J. d'Luna; et al. (1989). "A digital video signal post-processor for color image sensors". 1989 Proceedings of the IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference. Vol. 1989. pp. 24.2/1–24.2/4. doi:10.1109/CICC.1989.56823. S2CID 61954103.

A variety of CFA patterns can be used, with various arrangements of red, green, and blue (RGB) or of cyan, magenta, yellow, and white (CMYW) colors.

- ^ Sugiyama, Toshinobu, US patent application 20050231618, "Image-capturing apparatus" Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, filed March 30, 2005

- ^ "Fujifilm X-Trans sensor technology". Archived from the original on 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ^ Diallo, Amadou. "Adobe's Fujifilm X-Trans sensor processing tested". dpreview.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Adobe Improves X-Trans Processing in Lightroom CC Update: Promises More to Come". Thomas Fitzgerald Photography Blog. 17 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Sony Releases Stacked CMOS Image Sensor for Smartphones with Industry's Highest 48 Effective Megapixels". Sony Global - Sony Global Headquarters. Archived from the original on 2019-09-05. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ a b "How Tetracell delivers crystal clear photos day and night | Samsung Semiconductor Global Website". www.samsung.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ "IMX294CJK | Sony Semiconductor Solutions". Sony Semiconductor Solutions Corporation. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ "Product Releases | News & Events | OmniVision". www.ovt.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ US pending 20200280659, "Quad color filter array camera sensor configurations"

- ^ "Part 4: Non-Bayer CFA, Phase Detection Autofocus (PDAF) | TechInsights". techinsights.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ "Samsung's 108Mp ISOCELL Bright HM1 Delivers Brighter Ultra-High-Res Images with Industry-First Nonacell Technology". news.samsung.com. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

External links

[edit]- RGB "Bayer" Color and MicroLenses, Silicon Imaging (design, manufacturing and marketing of high-definition digital cameras and image processing solutions)

- eLynx image processing library, Big set of Bayer mosaic manipulation source code licensed under the GPL.

- Efficient, high-quality Bayer demosaic filtering on GPUs

- Global Computer Vision

- Review of Bayer Pattern Color Filter Array (CFA) Demosaicing with New Quality Assessment Algorithms

- Digital Camera Sensors

Bayer filter

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Purpose

The Bayer filter is a color filter array (CFA) consisting of a mosaic of red, green, and blue filters applied to the pixel array of a charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) image sensor.[1] This arrangement allows each photosite on the sensor to capture light intensity for only one color channel, producing a raw image known as a Bayer pattern mosaic. The primary purpose of the Bayer filter is to enable the capture of full-color images using a single image sensor, rather than requiring separate sensors for each color as in traditional three-chip systems.[6] By sampling red, green, and blue light at different pixels, it simplifies the hardware design, reduces manufacturing costs, and achieves greater compactness, making it ideal for consumer digital cameras and compact imaging devices.[6] Invented in 1976, this filter pattern has become the de facto standard for single-sensor color imaging in most modern cameras.[1] A key feature of the Bayer filter is its allocation of green filters to 50% of the pixels—twice as many as red or blue—to align with the human visual system's higher sensitivity to green wavelengths, which dominate luminance perception.[1] The resulting mosaic data requires post-capture demosaicing to interpolate missing color values and reconstruct a complete RGB image for each pixel.Historical Development

The Bayer filter was invented by Bryce E. Bayer, a researcher at Eastman Kodak Company, in 1976 as part of broader initiatives to develop cost-effective color imaging systems for single-chip digital sensors.[1] This innovation addressed the challenge of capturing full-color images without requiring multiple separate sensors for each primary color, thereby reducing complexity and expense in early digital camera prototypes.[7] The core design was detailed in U.S. Patent 3,971,065, filed on March 5, 1975, and granted on July 20, 1976, under the title "Color Imaging Array."[1] The patent outlined the RGGB pattern, which assigns twice as many filters to green as to red or blue to align with human visual sensitivity, prioritizing luminance information for sharper perceived images while sampling chrominance at lower frequencies.[1] Following its invention, the Bayer filter was integrated into Kodak's image sensors, with its initial commercial application in the Kodak DCS 200 series introduced in 1992, marking a key step in practical implementation within the company's development efforts.[8] By the 1990s, it gained widespread adoption in consumer digital cameras, notably through Kodak's DCS 200 series, which helped establish it as the dominant color filter array in the emerging market.[8] In the 2000s, the Bayer filter persisted as the standard CFA amid the industry's shift from CCD to CMOS sensor technologies, driven by CMOS advantages in power efficiency and integration that made digital imaging more accessible without necessitating a redesign of the color sampling approach.[9]Pattern and Operation

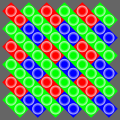

RGGB Mosaic Structure

The Bayer filter employs a repeating 2×2 mosaic pattern known as RGGB, where each unit consists of one red (R) filter, two green (G) filters, and one blue (B) filter arranged in an alternating grid across the sensor surface.[1] This structure forms continuous rows that alternate between RG and GB configurations, ensuring a balanced distribution of color sensitivities over the entire array.[10] The layout can be visualized as follows:Row 1: R G R G ...

Row 2: G B G B ...

Row 3: R G R G ...

Row 4: G B G B ...

Row 1: R G R G ...

Row 2: G B G B ...

Row 3: R G R G ...

Row 4: G B G B ...