Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cone cell

View on Wikipedia

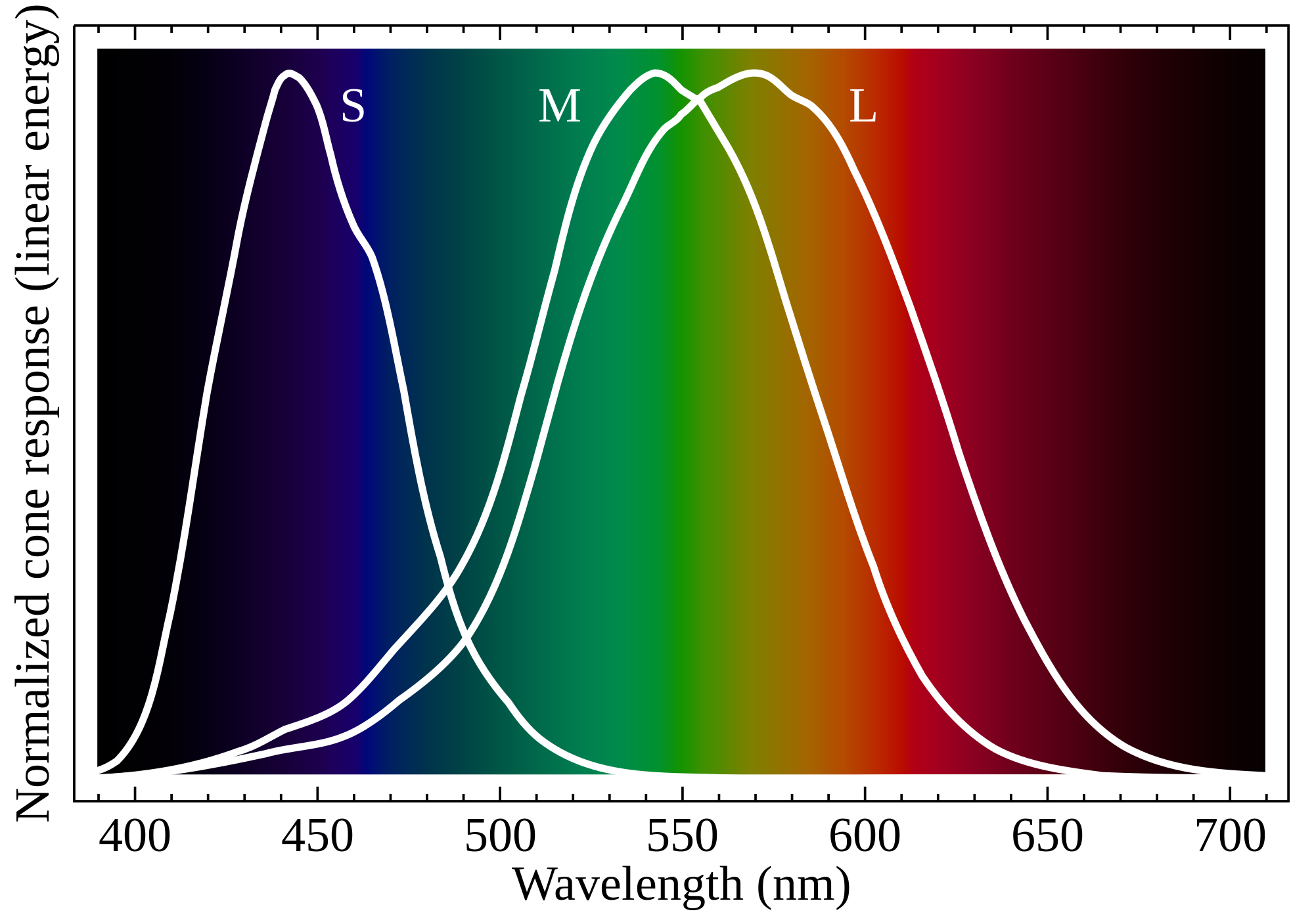

| Cone cells | |

|---|---|

Normalized responsivity spectra of human cone cells, S, M, and L types | |

| Details | |

| Location | Retina of vertebrates |

| Function | Color vision |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D017949 |

| NeuroLex ID | sao1103104164 |

| TH | H3.11.08.3.01046 |

| FMA | 67748 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

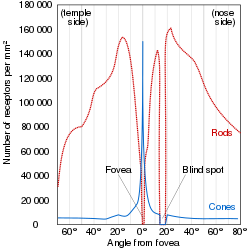

Cone cells or cones are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the vertebrate eye. Cones are active in daylight conditions and enable photopic vision, as opposed to rod cells, which are active in dim light and enable scotopic vision. Most vertebrates (including humans) have several classes of cones, each sensitive to a different part of the visible spectrum of light. The comparison of the responses of different cone cell classes enables color vision. There are about six to seven million cones in a human eye (vs ~92 million rods), with the highest concentration occurring towards the macula and most densely packed in the fovea centralis, a 0.3 mm diameter rod-free area with very thin, densely packed cones. Conversely, like rods, they are absent from the optic disc, contributing to the blind spot.[1]

Cones are less sensitive to light than the rod cells in the retina (which support vision at low light levels), but allow the perception of color. They are also able to perceive finer detail and more rapid changes in images because their response times to stimuli are faster than those of rods.[2] In humans, cones are normally one of three types: S-cones, M-cones and L-cones, with each type bearing a different opsin: OPN1SW, OPN1MW, and OPN1LW respectively. These cones are sensitive to visible wavelengths of light that correspond to short-wavelength, medium-wavelength and longer-wavelength light respectively.[3] Because humans usually have three kinds of cones with different photopsins, which have different response curves and thus respond to variation in color in different ways, humans have trichromatic vision. Being color blind can change this, and there have been some verified reports of people with four types of cones, giving them tetrachromatic vision.[4][5][6] The three pigments responsible for detecting light have been shown to vary in their exact chemical composition due to genetic mutation; different individuals will have cones with different color sensitivity.

Structure

[edit]Classes

[edit]Most vertebrates have several different classes of cone cells, differentiated primarily by the specific photopsin expressed within. The number of cone classes determines the degree of color vision. Vertebrates with one, two, three or four classes of cones possess monochromacy, dichromacy, trichromacy and tetrachromacy, respectively.

Humans normally have three classes of cones, designated L, M and S for the long, medium and short wavelengths of the visible spectrum to which they are most sensitive.[7] L cones respond most strongly to light of the longer red wavelengths, peaking at about 560 nm. M cones, respond most strongly to yellow to green medium-wavelength light, peaking at 530 nm. S cones respond most strongly to blue short-wavelength light, peaking at 420 nm, and make up only around 2% of the cones in the human retina. The peak wavelengths of L, M, and S cones occur in the ranges of 564–580 nm, 534–545 nm, and 420–440 nm nm, respectively, depending on the individual.[citation needed] The typical human photopsins are coded for by the genes OPN1LW, OPN1MW, and OPN1SW. The LMS color space is an often-used model of spectral sensitivities of the three cells of a typical human.[8][9]

Histology

[edit]

Cone cells are shorter but wider than rod cells. They are typically 40–50 μm long, and their diameter varies from 0.5–4.0 μm. They are narrowest at the fovea, where they are the most tightly packed. The S cone spacing is slightly larger than the others.[10]

Like rods, each cone cell has a synaptic terminal, inner and outer segments, as well as an interior nucleus and various mitochondria. The synaptic terminal forms a synapse with a neuron bipolar cell. The inner and outer segments are connected by a cilium.[2] The inner segment contains organelles and the cell's nucleus, while the outer segment contains the light-absorbing photopsins, and is shaped like a cone, giving the cell its name.[2]

The outer segments of cones have invaginations of their cell membranes that create stacks of membranous disks. Photopigments exist as transmembrane proteins within these disks, which provide more surface area for light to affect the pigments. In cones, these disks are attached to the outer membrane, whereas they are pinched off and exist separately in rods. Neither rods nor cones divide, but their membranous disks wear out and are worn off at the end of the outer segment, to be consumed and recycled by phagocytic cells.

Distribution

[edit]

While rods outnumber cones in most parts of the retina, the fovea, responsible for sharp central vision, consists almost entirely of cones. The distribution of photoreceptors in the retina is called the retinal mosaic, which can be determined using photobleaching. This is done by exposing dark-adapted retina to a certain wavelength of light that paralyzes the particular type of cone sensitive to that wavelength for up to thirty minutes from being able to dark-adapt, making it appear white in contrast to the grey dark-adapted cones when a picture of the retina is taken. The results illustrate that S cones are randomly placed and appear much less frequently than the M and L cones. The ratio of M and L cones varies greatly among different people with regular vision (e.g. values of 75.8% L with 20.0% M versus 50.6% L with 44.2% M in two male subjects).[12]

Function

[edit]

The difference in the signals received from the three cone types allows the brain to perceive a continuous range of colors through the opponent process of color vision. Rod cells have a peak sensitivity at 498 nm, roughly halfway between the peak sensitivities of the S and M cones.

All of the receptors contain the protein photopsin. Variations in its conformation cause differences in the optimum wavelengths absorbed.

The color yellow, for example, is perceived when the L cones are stimulated slightly more than the M cones, and the color red is perceived when the L cones are stimulated significantly more than the M cones. Similarly, blue and violet hues are perceived when the S receptor is stimulated more. S Cones are most sensitive to light at wavelengths around 420 nm. At moderate to bright light levels where the cones function, the eye is more sensitive to yellowish-green light than other colors because this stimulates the two most common (M and L) of the three kinds of cones almost equally. At lower light levels, where only the rod cells function, the sensitivity is greatest at a blueish-green wavelength.

Cones also tend to possess a significantly elevated visual acuity because each cone cell has a lone connection to the optic nerve, therefore, the cones have an easier time telling that two stimuli are isolated. Separate connectivity is established in the inner plexiform layer so that each connection is parallel.[13]

The response of cone cells to light is also directionally nonuniform, peaking at a direction that receives light from the center of the pupil; this effect is known as the Stiles–Crawford effect.

S cones may play a role in the regulation of the circadian system and the secretion of melatonin, but this role is not clear yet. Any potential role of the S cones in the circadian system would be secondary to the better established role of melanopsin (see also Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell).[14]

Color afterimage

[edit]Sensitivity to a prolonged stimulation tends to decline over time, leading to neural adaptation. An interesting effect occurs when staring at a particular color for a minute or so. Such action leads to an exhaustion of the cone cells that respond to that color – resulting in the afterimage. This vivid color aftereffect can last for a minute or more.[15]

Associated diseases

[edit]- Achromatopsia (rod monochromacy) – a form of monochromacy with no functional cones

- Blue cone monochromacy – a rare form of monochromacy with only functional S-cones

- Congenital red–green color blindness – partial color blindness where either one cone class is absent (dichromacy, including protanopia, deuteranopia & tritanopia) or the spectral sensitivity of one cone class is shifted (anomalous trichromacy, including protanomaly, deuteranomaly)

- Oligocone trichromacy – poor visual acuity and impairment of cone function according to ERG, but without significant color vision loss.[16]

- Bradyopsia – photopic vision has defects in detecting rapid changes in light .[16]

- Bornholm eye disease – X-linked recessive myopia, astigmatism, impaired visual acuity and red–green dichromacy.[16]

- Cone dystrophy – a degenerative loss of cone cells

- Retinoblastoma – a type of cancer originating from cone precursor cells

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Rods and Cones of the Human Eye". HyperPhysics Concepts - Georgia State University.

- ^ a b c Kandel, E.R.; Schwartz, J.H; Jessell, T. M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 507–513. ISBN 9780838577011.

- ^ Schacter, Gilbert, Wegner, "Psychology", New York: Worth Publishers,2009.

- ^ Jameson, K. A.; Highnote, S. M. & Wasserman, L. M. (2001). "Richer color experience in observers with multiple photopigment opsin genes" (PDF). Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 8 (2): 244–261. doi:10.3758/BF03196159. PMID 11495112. S2CID 2389566.

- ^ "You won't believe your eyes: The mysteries of sight revealed". The Independent. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

Equipped with four receptors instead of three, Mrs M - an English social worker, and the first known human "tetrachromat" - sees rare subtleties of colour.

- ^ Mark Roth (September 13, 2006). "Some women may see 100,000,000 colors, thanks to their genes". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on November 8, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

A tetrachromat is a woman who can see four distinct ranges of color, instead of the three that most of us live with.

- ^ Roorda, A.; Williams, D. R. (1999-02-11). "The arrangement of the three cone classes in the living human eye". Nature. 397 (6719): 520–522. doi:10.1038/17383. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10028967.

- ^ Wyszecki, Günther; Stiles, W.S. (1981). Color Science: Concepts and Methods, Quantitative Data and Formulae (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley Series in Pure and Applied Optics. ISBN 978-0-471-02106-3.

- ^ R. W. G. Hunt (2004). The Reproduction of Colour (6th ed.). Chichester UK: Wiley–IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-470-02425-6.

- ^ Brian A. Wandel (1995). Foundations of Vision. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ^ Foundations of Vision, Brian A. Wandell

- ^ Roorda A.; Williams D.R. (1999). "The arrangement of the three cone classes in the living human eye". Nature. 397 (6719): 520–522. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..520R. doi:10.1038/17383. PMID 10028967. S2CID 4432043.

- ^ Strettoi, E; Novelli, E; Mazzoni, F; Barone, I; Damiani, D (Jul 2010). "Complexity of retinal cone bipolar cells". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 29 (4): 272–83. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.005. PMC 2878852. PMID 20362067.

- ^ Soca, R (Feb 13, 2021). "S-cones and the circadian system". Keldik. Archived from the original on 2021-02-14.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L. Psychology: the second edition. Chapter 4.9.

- ^ a b c Aboshiha, Jonathan; Dubis, Adam M; Carroll, Joseph; Hardcastle, Alison J; Michaelides, Michel (January 2016). "The cone dysfunction syndromes: Table 1". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 100 (1): 115–121. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306505. PMC 4717370. PMID 25770143.