Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Brancacci Chapel

View on Wikipedia

The Brancacci Chapel (in Italian, "Cappella dei Brancacci") is a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, central Italy. It is sometimes called the "Sistine Chapel of the early Renaissance"[1] for its painting cycle, among the most famous and influential of the period. Construction of the chapel was commissioned by Felice Brancacci and began in 1422. The paintings were executed over the years 1425 to 1427. Public access is currently gained via the neighbouring convent, designed by Brunelleschi. The church and the chapel are treated as separate places to visit and as such have different opening times and it is quite difficult to see the rest of the church from the chapel.

The patron of the pictorial decoration was Felice Brancacci, descendant of Pietro, who had served as the Florentine ambassador to Cairo until 1423.[2] Upon his return to Florence, he hired Masolino da Panicale to paint his chapel. Masolino's associate, 21-year-old Masaccio, 18 years younger than Masolino, assisted, but during painting Masolino left to Hungary, where he was painter to the king, and the commission was given to Masaccio. By the time Masolino returned he was learning from his talented former student. However, Masaccio was called to Rome before he could finish the chapel, and died in Rome at the age of 27. Portions of the chapel were completed later by Filippino Lippi. During the Baroque period some of the paintings were seen as unfashionable and a tomb was placed in front of them.

The paintings

[edit]

In his frescos, Masaccio carries out a radical break from the medieval pictorial tradition, by adhering to the new Renaissance perspectival conception of space. Thus, perspective and light create deep spaces where volumetrically constructed figures move in a strongly individualised human dimension. Masaccio therefore continues on Giotto's path, detaching himself from a symbolic vision of man and propounding a greater realistic painting.[3] The cycle from the life of Saint Peter was commissioned as patron saint from Pietro Brancacci, the original owner of the chapel.[4]

The paintings are explained below in their narrative order.

The Temptation of Adam and Eve

[edit]

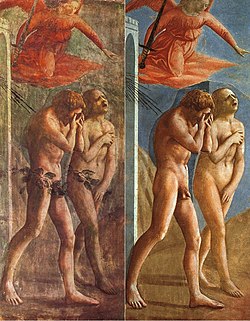

In contrast with Masaccio's Expulsion, this is a serene and innocent raffiguration.

The cycle begins with this painting by Masolino, placed on the higher rectangle of the arch delimiting the Chapel, within the pillar thickness. This scene and the opposite one (the Expulsion) are the premises to the story narrated in the frescos, showing the moment in which humans severed their union with God, later reconciled by Christ with Peter's mediation.

The painting shows Adam standing near Eve: they look at each other with measured postures, as she prepares to bite on the apple, just offered to her by the serpent near her arm around the tree. The snake has a head with thick blond hair, much idealised. The scene is aulic in its presentation, with gestures and style conveying tones of late International Gothic. Light, which models the figures without sharp angles, is soft and embracing; the dark background makes the body stand out in their sensual plasticity, almost suspended in space.

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

[edit]

Masaccio's masterpiece Expulsion from the Garden of Eden is the first fresco on the upper part of the chapel, on the left wall, just at the left of the Tribute Money. It is famous for its vivid energy and unprecedented emotional realism. It contrasts dramatically with Masolino's delicate and decorative image of Adam and Eve before the fall, painted on the opposite wall. It presents a dramatic intensity, with an armed angel who hovers over Adam and Eve indicating the way out of the Garden of Eden: the crying sinners leave at their backs the gates of Paradise.

This work represents a neat separation from the past International Gothic style; Masolino's serene composures are also left behind, and the two biblical progenitors are portrayed in dark desperation, weighed down under the angel's stern sight, who, with his unsheathed sword, forcibly expels them, with such a tension never seen before in painting. Gestures are eloquent enough: on exiting Paradise's Gates, from where some divine rays are shooting forward, Adam covers his face in desperation and guilt; Eve covers her nudity with shame and cries out, with a pained face. The bodies' dynamism, especially Adam's, gives an unprecedented passion to the figures, firmly planted on ground and projecting shadows from the violent light modelling them. Many are the details which increase the emotional drama: Adam's damp and sticky hair (on Earth, he'll struggle with hard labour and dirt), the angel's posture, foreshortened as if diving down from above. Eve's position is from an ancient representation, that of Venus Pudica (modest Venus). The foliage covering the couple's nudities was removed during a restoration in 1990.[5]

Peter's Calling

[edit]By Masolino.

In the left lunette, destroyed in 1746-48, Masolino had painted the Calling of Peter and Andrew, or Vocation, known thanks to some indications by past witnesses such as Vasari, Bocchi and Baldinucci. Roberto Longhi first identified an image of this lost fresco in a later drawing, which does not conform to the lunette's upper curvature, but appears today as a very probable hypothesis. In this scene, Masolino had divided his composition into two expanses, of sea and sky.

La Navicella

[edit]The opposite lunette housed the fresco of the Navicella, a traditional title for the scene where Christ, walking on water, rescues Peter from the surging waves of a storm and pulls him aboard the boat. This lunette again proposed a marine setting, on balance with the opposite scene and thus creating a sort of parable of Creation: from the skies of the Evangelists in the vault, to the seas of the upper register, to the lands and towns of the middle and lower registers, precisely like in Genesis. In a way, the viewer's sight shifts from Paradise to the terrene world in a consequential manner. Sources attribute this lunette to Masolino, but considering the alternating turns taken by the two artists on the scaffolding, some propound for a Masaccio fresco.[6]

Peter's Repentance

[edit]

Peter's Repentance is found in the left semi-lunette of the upper register, where a very schematic preparatory drawing of the sinopia[7] was hosted. The scene was attributed to Masaccio, on the basis of its greater incisiveness in the treatment as against Masolino's work.

The Tribute Money

[edit]

The most famous painting in the chapel is Tribute Money, on the upper left wall, with figures of Jesus and Peter shown in a three part narrative. The painting, largely attributed to Masaccio, represents the story of Peter and the tax collector from Matthew 17:24–27. The left side shows Peter getting a coin from the mouth of a fish and the right side shows Peter paying his taxes. The whole appears to be related to the establishment of the Catasto, the first income tax in Florence, in the time the painting was being executed.[8]

The miracle is not represented in a hagiographic key, but as a human occurrence that posits a divine decision: a historical event, then, with an explicit and indubitable moral meaning. On the narrational plane, the Tribute is developed in three stages: in the central part, Christ, from whom the tax collector asks a tribute for the Temple, orders Peter to go and fetch a coin from the mouth of the first fish he can catch; on the left, Peter, squatting on the shore, takes the coin from the fish; on the right, Peter tenders the coin to the tax collector. The three stages unite and the temporal sequences are expressed in spatial measures. The absence of a chronological scansion in the narrative, is to be sought in the fact that the painting's salient motif is not so much the miracle, as the actuation of the Divine Will, expressed by Jesus' the imperative gesture. His will becomes Peter's will who, by repeating his Lord's gesture, simultaneously indicates the fulfillment of Christ's will. The apostles' solidarity is shown by their serrated grouping around Jesus, as if to form a ring, a "coliseum of men".[9] However, the very task is given to Peter: he alone will have to deal with mundane institutions. The portico's pillar becomes a symbolic element of separation between the grouped apostles and the conclusive delivery of tribute to the tax collector on Peter's part.

In the central group, the transverse directions formed by Christ's gesture with his right arm – replicated by that of Peter and, in opposite, by the turned collector – cross with those formed by the gestures of the right group, emphasizing escape points placed in the deepest space.[10]

Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha

[edit]The upper scene on the right wall shows, on the left side, the Healing of the Cripple and, on the right side, the Raising of Tabitha. The fresco is generally attributed to Masolino,[11] although Masaccio's hand has been discovered by some scholars. The scene shows two different episodes, with St. Peter appearing in both of them enclosed in a scenario of a typical Tuscan city of the 15th century depicted according to the strict rules of central perspective. The latter is generally regarded as Masaccio's main contribution, whereas the two central figures show Gothic influences.

St Peter Preaching

[edit]On the upper left wall one can see St Peter Preaching by Masolino, completed in eight days. Peter is shown, with an expressive gesture, preaching in front of a crowd. The people in the group have many and varied demeanours, from the sweet attention of the veiled nun in the foreground, to the sleepiness of both the girl behind her and the bearded old man, to the fear of the woman at back, whose worried eyes only can be seen. Mountains seem to continue from the preceding scene, with a spatial unity that was one of Masaccio trademarks. The three heads behind St Peter are probably portraits of contemporary people, same as the two friars on the right: all were formerly attributed to Masaccio.[12]

Baptism of the Neophytes

[edit]By Masaccio.

The whole composition presents details of astounding realism: the trembling neophyte, the water droplets from the baptised hair, the white sheet being removed in the background. Chromatic effects of "cangiantismo",[13] where drapery is modelled using contrasting colours to create an effect that simulates cangiante textiles, is achieved by Masaccio through a pictorial technique based on the juxtaposition of complementary colours, later reprised by Michelangelo.[14]

St Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow

[edit]

Lower centre wall, left side, by Masaccio. The episode depicts Acts 5:12–16.

The picture's attribution to Masaccio is based in on the perspective structure used to create the street setting and the craggy naturalism of the physiognomies of the old man and the cripple. According to Federico Zeri, Masaccio's brother, the painter Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi, known as Lo Scheggia, may have served as the model for the apostle John and the old bearded man in the background is a possible portrait of Donatello.[15]

The Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias

[edit]

Lower centre wall, right side, by Masaccio.

According to the narrative in Acts 4:32;5:1–11, each Christian, after selling their own possessions, would bring the proceeds to the apostles, who distributed to everyone according to need. Only Ananias "kept back for himself some of the proceeds and brought only a part of it and laid it at the apostles' feet." Severely reprimanded by Peter, he fell to the ground and died. The composition concentrates on the moment in which Ananias lies on the ground, whilst the woman with child receives alms from Peter, accompanied by John. The compositional structure is quite tight and emotional, involving the viewer in the heart of the event.[16]

Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St. Peter Enthroned

[edit]Lower left wall, by Masaccio, completed by Filippino Lippi approximately fifty years later.

Filippino composed the five bystanders on the left, the Carmelites' drapery and the central part of St. Peter's arm in the "enthroned" representation. According to the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) by Jacobus de Voragine, after release from prison, St. Peter resuscitates, with St Paul's assistance, Theophilus's son, who had died fourteen years before.[17] So, people venerated St Peter and erected a new church to him, where he is enthroned so as to be revered and prayed by all.[18] However, the true meaning of this fresco rests with the politics of the time: that is, in the conflict between Florence and the Duchy of Milan.[19]

There is a precise iconographic resemblance between Theophilus (seated on the left, in an elevated position within a niche) and Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Florence's bitter enemy. The latter was a feared tyrant, whose thirst for power pushed him to start a war with Florence, almost destroying its freedom. Memory of this episode returned in all its crude vividness, when Florence had to confront a dispute with Filippo Maria Visconti, Gian Galeazzo's son. The figure sitting on Theophilus' (i.e., Gian Galeazzo's) right would be the Florentine chancellor Coluccio Salutati, author of an invective against the Lombard lord. St Peter's presence, therefore, symbolizes the mediating role of the Church in the person of Pope Martin V, to sedate the conflict between Milan and Florence. At the extreme right, a group of four bystanders should personify Masaccio (looking away from the painting), Masolino (the shortest one), Leon Battista Alberti (in the foreground); and Filippo Brunelleschi (the last). The frequent use of portraiture makes the imaginary world of painting and the viewer's personal experience converge. For Masaccio's contemporaries it should have been easier to read this scene as a reflection of themselves and their own social realities. The fresco's figures populate a dilated space of their own world and have a natural demeanor: they stretch their necks to see better, they look over their neighbour's shoulder, gesticulate, observe, and gossip about the event with the next bystander.[20]

|

|

St Paul Visiting St Peter in Prison

[edit]By Filippino Lippi.

The cycle continues towards the left, on the pillar, in the lower register, with the scene of St Peter in Prison visited by St Paul, painted by Filippino Lippi. St Peter is visible at a window with bars, while the visitor gives his back to the viewer. Perhaps the scene followed a drawing by Masaccio, as shown by the perfect architectural continuity with the adjacent scene of the Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus.

Decoration of the Brancacci Chapel stayed incomplete due to Masaccio's departure to Rome in 1427, where he died a year later. Moreover, the commissioning patron's exile in 1436 hindered any possibility of the frescos completion by other artists; in fact, it is probable that some parts already painted by Masaccio were removed as a sort of damnatio memoriae, because of their portraiture of the Brancacci family members. Only with the return of this family to Florence in 1480, the frescos could be resumed, by commissioning the artist closer and more faithful to the great Masaccio tradition, that is to say, Filippino Lippi, the son of his first apprentice. Filippino's intervention is not documented with precision, but is datable to ca. 1485 thanks to some indications given by Giorgio Vasari.[21]

St Peter Being Freed from Prison

[edit]Lower right wall, right side. By Filippino Lippi.

This is the last scene, to be related to the imprisoned saint on the opposite wall. In fact, it shows St Peter's liberation from prison by an angel, and it's entirely attributable to Filippino Lippi. Here too the architecture is connected with that of the adjacent depiction. The sword-armed guard sleeps in the foreground, leaning on a stick, whilst the miraculous rescue is happening – this implies Christian salvation, as well as perhaps Florence's recovered autonomy after the contention with Milan.

Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of St Peter

[edit]Lower right wall, centre. By Filippino Lippi.

The large panel in the lower register, right wall, is by Filippino Lippi. Outside the city walls, (in Rome, as indicated by the Pyramid of Cestius along the Aurelian Walls and by the edifices peeking from the merlons) one may see, on the right, the disputation between Simon Magus and St Peter in front of Nero, with a pagan idol lying at the latter's feet. On the left, Peter's crucifixion is taking place: the saint is hanging upside down because he refused to be crucified in the same position as Christ's. The scene is replete with portraits: the youth with a beret on the extreme right is Filippino's self-portrait. The old man with a red hat in the group near St Peter and Simon Magus, is Antonio del Pollaiuolo. The young man below the archway and looking towards the viewer, is a portrait of Sandro Botticelli, Filippino's friend and teacher. In Simon Magus, some critics wish to see the poet Dante Alighieri, celebrated as the creator of the renowned Italian vernacular used by Lorenzo il Magnifico and Agnolo Poliziano.

Layout of the painting complex

[edit]- Left wall

Left wall, higher part II. Expulsion of Adam and Eve (Masaccio), V. Tribute (Masaccio), IX. St Peter Preaching (Masolino, detail)

Left wall, lower part XIII. St Paul Visiting St Peter in Prison (Filippino Lippi, unrestored), XV. Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned (Masaccio and Filippino Lippi), XI. St Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow (Masaccio)

- Right wall

Right wall, higher part X. Baptism of the Neophytes (Masaccio), VI. Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha (Masolino), I=Original Sin (Masolino)

Influence

[edit]Masaccio's application of scientific perspective, unified lighting, use of chiaroscuro and skill in rendering the figures naturalistically established new traditions in Renaissance Florence that some scholars credit with helping to found the new Renaissance style.[22]

The young Michelangelo was one of the many artists who received his artistic training by copying Masaccio's work in the chapel. The chapel was also the site of an assault on Michelangelo by rival sculptor Pietro Torrigiano, who resented Michelangelo's critical remarks about his draughtsmanship. He punched the artist so severely that he "crushed his nose like a biscuit" (according to Benvenuto Cellini)[23] which deformed Michelangelo's face into that of a boxer's.

Restoration

[edit]The first restoration of the chapel frescoes was in 1481-1482, by Filippino Lippi, who was also responsible for completing the cycle. Due to the lamps used for lighting the dark chapel, the frescoes were relatively quickly coated in dust and dirt from the smoke. Another restoration was conducted at the end of the 16th century. Around 1670, sculptures were added, and the fresco-secco additions were made to the frescoes, to hide the various cases of nudity. Late 20th century restoration removed the overpainting and collected dust and dirt. Some critics, including professor and art historian James H. Beck,[24] have criticised these efforts, while others, including professors, historians and restorers, have praised the work done on the chapel.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Cf. B. Berenson, The Italian Painters Of The Renaissance, Pahidon (1952).

- ^ K. Shulman, Anatomy of a Restoration: The Brancacci Chapel (1991), p. 6. Cf. also A. Ladis, Masaccio: la Cappella Brancacci (1994), passim.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, Rizzoli (1999), p. 28.

- ^ "The Brancacci Chapel and the Use of Linear Perspective". Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Cf. John Spike, Masaccio, cit. (2002); Mario Carniani, La Cappella Brancacci a Santa Maria del Carmine, cit., (1998).

- ^ Cf. John Spike, Masaccio, Rizzoli, Milan (2002), s.v. "Navicella".

- ^ The sinopia is the underdrawing for fresco made with reddish, greenish or brownish earth colour with water brushed on the arriccio layer, over which the intonaco is applied before painting. Red earth (iron oxide) mined by the town of Sinopia during the Renaissance period (present Turkey), currently depleted, gave the name to the method. During Giotto times and before Sinopia was the main preparatory drawing - the entire fresco was designed in Sinopia directly on the wall. Cartoons were implemented later after the perspective was "invented" and more thorough composition development became essential. Arriccio (Ariccio; Arricciato, Arriccato) or Browncoat is a layer of plaster over the roughcoat (Trullisatio) and just under the finish coat of plaster (Intonaco) which will be painted. The sinopia or full scale composition is laid out on the arriccio.

- ^ Cf. F. Antal, La pittura fiorentina e il suo ambiente sociale nel Trecento e nel primo Quattrocento, Turin (1960), s.v. "Catasto" and passim; see also R. C. Trexler, Public Life in Renaissance Florence, Ithaca (1980), Pt. 1, Ch. 1, pp. 9–33.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., pp. 30–31.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., p. 31.

- ^ Cf. U. Baldini, O. Casazza, La Cappella Brancacci, Milan (1990).

- ^ U. Procacci, Masaccio. La Capella Brancacci, Florence (1965), s.v. "Predica di san Pietro".

- ^ Cf. definition at "Cangiantismo". Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2012..

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., p. 29.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., p. 32.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., p. 33.

- ^ Jacobus de Voragine. "44. The Chair of Saint Peter". In The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, translated by William Granger Ryan, 1.162–1.166. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1993. Theophilus was a prefect of Antioch.

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., pp. 34–35.

- ^ Cf. R. C. Trexler, Public Life in Renaissance Florence, cit., s.v. "Milan"

- ^ Cf. Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, cit., pp. 34-35; see also F. Antal, La pittura fiorentina e il suo ambiente sociale nel Trecento e nel primo Quattrocento, cit., ibid.; M. Carniani, "La Cappella Brancacci a Santa Maria del Carmine", in AA.VV., Cappelle del Rinascimento a Firenze, Florence (1998).

- ^ M. Carniani, "La Cappella Brancacci a Santa Maria del Carmine", cit.

- ^ Cf. O. Casazza, Masaccio, Florence (1990), s.v. "Stile rinascimentale".

- ^ Cf. H. Hibbard, Michelangelo, Folio Society (2007), p. 12.

- ^ Cf. int. al. Philadelphia Museum of Art, article "Italian Paintings 1250-1450"; see also The Florentine Badia by Anne Leader (2000).

External links

[edit]Brancacci Chapel

View on GrokipediaLocation and Historical Context

Position within Santa Maria del Carmine

The Brancacci Chapel occupies the south transept of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine, a Carmelite church in Florence's Oltrarno district.[3][1] The church itself was established in 1268 by Carmelite friars originating from Pisa, forming part of a larger convent complex that expanded over subsequent centuries.[3] Construction of the chapel as a dedicated family space began around 1386, effectively extending the south arm of the transept to create a self-contained barrel-vaulted enclosure with an altar niche, positioned to align with the church's cruciform plan while allowing separation for private devotion.[1] This addition stemmed from provisions in the 1367 will of Pietro Brancacci, an early family member, though the Brancacci acquired formal rights to the site toward the late 14th century.[1][2] Architecturally, the chapel's placement integrates it into the transept's eastern wall, facing the nave and high altar, which facilitated visibility during liturgical events while preserving the family's commemorative function amid the church's Gothic origins—later overlaid with Baroque reconstruction following a 1771 fire that spared the chapel due to its semi-independent structure.[1] Modern access occurs via a dedicated museum entrance adjacent to the convent cloister at Piazza del Carmine 14, bypassing the main church interior to protect the frescoes from environmental damage and visitor traffic.[3]Architectural Features and Original Setup

The Brancacci Chapel occupies the right arm of the transept in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, forming a compact rectangular space designed specifically for familial patronage and liturgical use. Commissioned around 1422 by Felice Brancacci, its architecture integrated seamlessly with the intended fresco program, featuring plain walls subdivided into upper and lower registers to accommodate narrative scenes, separated by simulated architectural moldings painted in trompe l'oeil to unify the pictorial and structural elements. The ceiling consisted of a cross-vault, providing a modest height suitable for intimate viewing while allowing for painted decoration on the vault surfaces themselves.[4][5] Illumination derived primarily from a single tall, narrow two-light window positioned above the altar on the rear wall, which cast natural light from behind the viewer entering from the transept door, creating directional shadows that aligned with the frescoes' modeled figures for enhanced spatial illusionism. The altar, originally dedicated to Saint Peter in line with the chapel's thematic focus, incorporated a painting of the Madonna del Popolo, positioning the sacred space for both private devotion and public contemplation of the life of Saint Peter depicted around it. This setup emphasized causal integration of light, architecture, and imagery, with the window's placement influencing the fresco compositions' orientation and depth perception.[4][5][6] Subsequent modifications altered the original configuration: following Brancacci's exile in 1436 and formal condemnation in 1458, the chapel was re-consecrated to the Madonna del Popolo, with the final fresco (Saint Peter's Crucifixion, likely below the window) whitewashed and destroyed; by 1670, gilded wooden frames and sculptures divided the registers, and the cross-vault was eventually replaced with a small dome, though restorations have aimed to recover the pre-18th-century state where possible. These changes, including post-1771 fire reconstructions, obscured but did not erase evidence of the initial design's emphasis on unadorned surfaces primed for fresco adhesion and unified visual narrative.[4][5][7]Patronage and Commissioning

Felice Brancacci's Role and Background

Felice Brancacci (c. 1382–after 1447) was a Florentine patrician and prosperous silk merchant engaged in Levantine trade, whose wealth and status positioned him as the key patron for the Brancacci family chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine.[8][9] Active in politics, he occupied roles such as gonfaloniere di compagnia in 1412, captain of the Guelf party in 1420, podestà of Pisa in 1421, and prior in 1423, underscoring his integration into the republic's administrative elite.[10] In 1422, Brancacci undertook a diplomatic embassy to Cairo as Florentine ambassador to Mamluk Sultan Al-Ashraf Barsbay, seeking to advance trade ties and protect the city's currency amid Mediterranean commerce challenges; his detailed diary of the journey documents cross-cultural negotiations and personal hardships encountered.[9] These experiences informed his subsequent artistic commissions, linking his mercantile ventures to themes of authority and redemption in religious iconography. Upon returning to Florence, Brancacci exercised his family's longstanding rights to the chapel—acquired generations earlier—and commissioned its fresco decoration in the mid-1420s, engaging Masolino da Panicale and Masaccio to depict the life of Saint Peter across the walls.[10][11] This program, initiated around 1425, served to elevate the Brancacci lineage's prestige within Carmelite devotion, with specific motifs like the Tribute Money echoing Brancacci's Egyptian diplomacy by portraying fiscal obedience to secular powers.[9] His second marriage to Lena Strozzi in 1431 further allied him with influential anti-Medicean networks, though political reversals later curtailed his direct oversight of the project.[10]Contract Details and Intended Purpose

The decoration of the Brancacci Chapel was commissioned by Felice di Michele Brancacci, a Florentine silk merchant, diplomat, and member of the city's political elite, who held the chapel as a family patronage right inherited from earlier Brancacci generations dating to the late 14th century.[12][13] No surviving contract document specifies the exact terms, payments, or timelines, though archival evidence from Florentine catasti (tax declarations) and patronage records confirms Brancacci's role in funding the project, with construction of the chapel space initiated around 1422 and fresco work commencing by 1424-1425.[8][14] The intended purpose centered on establishing a votive and funerary space for the Brancacci family within the Carmelite church, featuring a fresco cycle that linked Genesis narratives of Original Sin—painted in the upper register—with scenes from the life of Saint Peter below, symbolizing redemption through apostolic authority and ecclesiastical mediation of sin.[15][13] This program reflected Brancacci's personal devotion, possibly influenced by his 1422 diplomatic mission to Egypt where he encountered Eastern Christian traditions emphasizing Petrine primacy, as well as broader Florentine mercantile piety tying family legacy to salvific theology.[16] The chapel served practical functions including family burials and Masses, aligning with 15th-century Italian patronage norms where such commissions reinforced social status, spiritual intercession, and alignment with mendicant orders like the Carmelites.[12]Artists Involved

Masolino da Panicale's Initial Work

Masolino da Panicale, born Tommaso di Cristoforo Fini around 1383, received the commission to decorate the Brancacci Chapel from Felice Brancacci following the chapel's construction starting in 1422.[17] Work on the frescoes commenced circa 1424, with Masolino executing initial scenes in the upper register of the chapel walls as part of a planned cycle illustrating Original Sin and the life of Saint Peter.[17] [18] Masolino's contributions included three primary panels: The Temptation, located in the upper left lunette alongside Masaccio's subsequent Expulsion from Paradise; The Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha on the right wall; and Saint Peter Preaching adjacent to it.[17] These works, painted between 1424 and 1427, employed fresco technique on the chapel's barrel-vaulted surfaces, adhering to the Carmelite order's iconographic requirements for narrative clarity and theological emphasis.[17] His figures exhibit elongated proportions and graceful poses characteristic of International Gothic influences, contrasting with the emerging volumetric naturalism later introduced by Masaccio.[19] The initial phases under Masolino established the chapel's compositional framework, dividing the walls into three horizontal registers with lunette scenes above and narrative episodes below, facilitating a continuous visual storytelling.[17] Payments recorded in Brancacci's accounts confirm Masolino's active role through 1427, after which his departure—possibly for commissions in Hungary—halted progress on his assigned portions.[17] This foundational work laid the groundwork for the chapel's evolution into a pivotal site for Renaissance artistic innovation, though Masolino's more decorative approach preserved late medieval conventions in posture and drapery rendering.[19]Masaccio's Innovations and Contributions

Masaccio's contributions to the Brancacci Chapel frescoes, painted between 1425 and 1427, marked a pivotal shift toward scientific naturalism in Western art, departing from the stylized forms of the International Gothic prevalent in Masolino's sections.[20] His innovations emphasized empirical observation and mathematical precision, drawing on Filippo Brunelleschi's demonstrations of linear perspective to create illusions of three-dimensional space within the flat fresco medium.[20] In The Tribute Money, Masaccio orchestrated orthogonals—lines representing architectural elements and gestures—to converge at a single vanishing point aligned with Christ's head, establishing a coherent horizon line and recession that integrated multiple narrative episodes into a unified architectural setting.[21] This systematic application of one-point perspective was among the earliest in painting, enabling viewers to perceive the scene as an extension of the chapel's real space.[20] Complementing linear perspective, Masaccio incorporated atmospheric perspective, where distant elements fade in clarity and color saturation, as seen in the hazy background landscape of The Tribute Money, which augments spatial depth without relying solely on geometry.[21] Foreshortening further enhanced realism, particularly in The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, where Eve's elongated neck and Adam's straining limbs suggest bodily distortion consistent with their recession into depth, grounded in anatomical accuracy rather than decorative elongation.[21] Figures throughout exhibit contrapposto stances and proportional solidity derived from classical sculpture, with volumetric modeling achieved through chiaroscuro—graduated light and shadow that sculpts forms as if illuminated by a single external source matching the chapel's ambient light.[20] In St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow, cast shadows project realistically from Peter's form onto the ground, reinforcing spatial continuity and the causal interplay of light with matter.[21] Masaccio's emphasis on emotional verisimilitude distinguished his work, as in The Expulsion, where Adam and Eve's faces contort in raw grief—Adam covering his eyes in despair, Eve wailing with open mouth—conveying psychological depth absent in prior religious iconography.[20] These elements collectively prioritized observable human anatomy, gesture, and environmental interaction over symbolic abstraction, influencing artists like Michelangelo and laying foundational principles for Renaissance figural representation.[20] The frescoes' execution in buon fresco technique ensured durability while allowing rapid application of wet plaster to capture fluid, lifelike drapery folds and textures.[1]

Filippino Lippi's Later Completion

The Brancacci Chapel fresco cycle, initiated by Masolino da Panicale and Masaccio in the 1420s, remained incomplete following Masaccio's death in 1428 and Masolino's departure for Hungary.[1] Over fifty years later, Filippino Lippi, son of the painter Fra Filippo Lippi and a pupil of Sandro Botticelli, was tasked with finishing the unfinished sections and restoring damaged areas between 1481 and 1485.[22] [23] This commission marked Lippi's first major independent project, during which he overpainted effaced faces in existing frescoes and executed new scenes to bring the narrative of Saint Peter's life to conclusion.[24] [23] Lippi completed Masaccio's Raising of the Son of Theophilus and Saint Peter Enthroned on the left wall's lower register, integrating his contributions seamlessly with the earlier master's work while adding contemporary portraits, including possible depictions of Florentine notables.[22] He painted Saint Paul Visiting Saint Peter in Prison on an adjacent pilaster and the expansive Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of Saint Peter on the opposite entrance wall, depicting the apostle's final trials and martyrdom in a manner that emphasized dramatic narrative and intricate architectural backdrops.[22] [25] These additions adhered to the original iconographic program focused on redemption through Saint Peter's authority, linking the Genesis scenes of original sin to apostolic miracles and sacrifice.[1] Stylistically, Lippi's frescoes reflect the evolved quattrocento aesthetic of the 1480s, featuring denser compositions, heightened decorative detail, and softer, more fluid figures compared to Masaccio's pioneering naturalism, linear perspective, and sculptural volume from the 1420s.[24] [13] His work incorporates Botticellian grace and elaborate costumes, introducing a tenderness and narrative richness that contrasted with the earlier artists' focus on spatial innovation and emotional directness, yet preserved the chapel's didactic unity.[24] Lippi also included a self-portrait among the observers in the Raising of the Son of Theophilus, a common practice for artists asserting their role in collaborative endeavors.[26] This completion not only restored the chapel's visual coherence but also bridged early and high Renaissance techniques, influencing subsequent generations of Florentine painters.[13]Fresco Cycle Overview

Iconographic Program: Original Sin and St. Peter

The iconographic program of the Brancacci Chapel juxtaposes scenes of Original Sin with the life of St. Peter to articulate a theological progression from humanity's primordial fall to redemption through ecclesiastical authority and sacraments. Commissioned around 1424, the cycle begins on the entrance wall with Masolino da Panicale's Temptation of Adam and Eve and Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, both executed between 1425 and 1427, which depict the Genesis narrative of disobedience leading to sin, shame, and exile from paradise.[27][21] These panels establish the human condition of inherited guilt and mortality, setting a doctrinal foundation for the subsequent frescoes.[27] St. Peter's cycle, comprising the majority of the chapel's walls, illustrates his ministry as the divinely appointed instrument of salvation, directly countering the consequences of Original Sin through acts symbolizing forgiveness, healing, and baptismal renewal. Key scenes such as the Baptism of the Neophytes and Healing the Sick with His Shadow, painted by Masaccio circa 1426, evoke the cleansing of sin via water and shadow—metaphors for sacramental grace administered by the Church, of which Peter is the foundational "rock" (Matthew 16:18).[21][27] Peter's own repentance after denying Christ parallels Adam's transgression, underscoring themes of fallibility and restoration, while his miracles affirm the Church's role in mediating divine mercy to the afflicted.[27] This integration reflects Carmelite and early Renaissance emphases on causal realism in salvation history: the Expulsion's raw emotionalism—Masaccio's figures convey irreversible loss through linear perspective and volumetric modeling—contrasts with Peter's authoritative composure in later panels, symbolizing progression from despair to ecclesial hope.[21] The program's coherence, despite multiple artists, prioritizes Peter's apostolic legacy as the antidote to original guilt, aligning with patron Felice Brancacci's probable devotion to papal and civic redemption narratives.[27][21]Techniques and Materials Employed

The frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel were primarily executed in the buon fresco technique, whereby natural pigments ground with water were applied directly onto freshly laid lime plaster, or intonaco. This method allowed the mineral pigments to chemically bind with the calcium hydroxide in the plaster as it carbonated and dried, forming insoluble carbonates that ensured long-term adhesion and resistance to flaking. The process demanded precise timing, as the intonaco was applied in small sections, or giornate, corresponding to the area that could be completed before the plaster set, typically within a day.[28] Beneath the intonaco layer lay the coarser arriccio preparatory plaster, upon which sinopia underdrawings were incised or painted using reddish iron oxide pigments to outline compositions and guide the final painting. Full-scale cartoons were likely employed for transferring detailed designs via pouncing or incision, facilitating the accurate rendering of complex scenes and figures. Some adjustments, or pentimenti, are evident in surviving sinopia traces, revealing iterative refinements by the artists.[29] Pigments included earth-based colors such as ochres and umbers for tones, vermilion for reds, and malachite for greens, as identified through spectroscopic analysis of Masaccio's works like the healing of the invalids. Blues were achieved with azurite or less costly alternatives, though lapis lazuli was rare in these frescoes due to cost. Limited a secco overpainting occurred in original execution for fine details or corrections not compatible with wet plaster, though extensive a secco additions were later applied around 1670 to obscure nudity. Restoration efforts, including 1980s cleanings and 2023-2024 interventions, employed non-destructive reflectance spectroscopy to confirm pigment identities and monitor color stability, revealing brighter original greens post-removal of accretions.[30][31][32]Original Sin Frescoes

The Temptation of Adam and Eve

The Temptation of Adam and Eve, executed by Masolino da Panicale as part of the Brancacci Chapel fresco cycle, depicts the biblical scene from Genesis 3 where Eve receives the forbidden fruit from the serpent and offers it to Adam.[33] This fresco, located in the upper register on the entrance arch of the chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, measures approximately 2.08 meters in height and forms the initial panel introducing the theme of Original Sin.[22] Painted in fresco technique between 1424 and 1425, it adheres to traditional iconography prevalent in early 15th-century Italian art, featuring Adam and Eve nude in a paradisiacal setting with the Tree of Knowledge at center.[34] Masolino portrays Eve extending the apple toward Adam, who reaches for it with a gesture of acceptance, while the serpent coils around the tree branch above, its head aligned with Eve's.[35] The figures exhibit graceful, elongated proportions and soft contours characteristic of Masolino's elegant style, influenced by International Gothic traditions, with minimal emotional expression—Eve's face serene and Adam's gaze direct yet vacant, suggesting unawareness of impending consequences.[36] Against a dark, neutral background that emphasizes the static poses, the composition lacks deep spatial recession, prioritizing decorative linearity over volumetric modeling.[37] This panel's stylistic approach contrasts with the subsequent Expulsion by Masaccio on the opposite wall, highlighting Masolino's preference for idealized beauty and surface ornamentation rather than dramatic realism or psychological depth.[27] Scholarly analysis attributes the work's attribution to Masolino based on its lighter palette, fluid drapery folds, and overall refinement, distinguishing it from Masaccio's heavier forms and chiaroscuro effects elsewhere in the cycle.[38] The fresco's survival intact, following 1980s restorations that removed overpainting, reveals original vibrant colors and subtle gilding on the serpent, underscoring Masolino's role in bridging Gothic elegance with emerging Renaissance naturalism.[39]The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden is a fresco executed by Masaccio circa 1424–1427 in the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, measuring approximately 7 feet by 2 feet 11 inches.[40] It occupies the right section of the upper register on the chapel's entrance wall, complementing Masolino da Panicale's adjacent Temptation to narrate the Fall. The composition portrays the angel with flaming sword herding Adam and Eve from paradise, with Adam averting his face in shame while covering his genitals and Eve gesturing in grief, her hands shielding her breasts as tears stream down her face.[40] [35] Masaccio's application of buon fresco technique involved pigment on wet plaster in daily sections (giornate), yielding durable integration with the wall surface.[40] The figures exhibit naturalistic anatomy, with Adam's robust musculature conveying physical weight and Eve's contrapposto pose echoing classical Venus pudica motifs, departing from medieval stylization toward volumetric form through chiaroscuro modeling.[35] A unified light source from the viewer's left casts consistent shadows, including ground shadows from the figures—the first such depiction in Western art since antiquity—enhancing spatial coherence and realism.[35] [40] Foreshortening on the angel's form projects depth, while the barred gate of Eden recedes angularly amid a barren landscape, symbolizing exile's desolation.[40] This emotional intensity—evident in the protagonists' distorted features and dynamic gestures—contrasts Masolino's static Temptation, underscoring Masaccio's innovation in conveying psychological turmoil and human fallibility, pivotal to the chapel's redemption theme via Saint Peter's life.[35] The work's raw naturalism, prioritizing observable human proportions over idealization, influenced subsequent Renaissance masters by reintroducing empirical observation in figure depiction after a millennium of symbolic abstraction.[40]Life of St. Peter Frescoes

Peter's Calling and Early Ministry

The original iconographic program of the Brancacci Chapel included a fresco depicting the calling of Saints Peter and Andrew by Jesus Christ, painted by Masolino da Panicale in the left lunette of the entrance wall, but this scene was destroyed during the chapel's reconstruction between 1746 and 1748.[25] [41] Surviving frescoes illustrate pivotal moments from Peter's early apostolic activities. Masolino's St. Peter Preaching, positioned on the upper register near the entrance, portrays the apostle delivering a sermon to a gathered crowd, drawing from accounts in the Acts of the Apostles where Peter addresses Jews in Jerusalem following Pentecost. The composition features Peter in a dynamic pose, gesturing to emphasize his message, surrounded by listeners including figures in contemporary Florentine attire, underscoring the relevance to the chapel's patrons.[42] Complementing this is Masaccio's Baptism of the Neophytes (1426–1427), adjacent on the same wall, which depicts Peter overseeing the baptism of new converts emerging nude from a river, symbolizing the rapid growth of the early Christian community as described in Acts 2:41. Measuring 255 by 162 cm, the fresco employs volumetric modeling and atmospheric perspective to convey depth and realism, with light illuminating the wet skin of the neophytes and the architectural elements in the background.[43] Masaccio's The Tribute Money, located nearby on the opposite wall, narrates the episode from Matthew 17:24–27 in a continuous narrative across three registers: the tax collector confronting Jesus and the apostles, Peter paying the tribute, and Peter extracting a coin from a fish's mouth by the lakeside. This scene, executed around 1425–1427, highlights Peter's obedience and the miraculous provision during his time as a disciple, establishing his authority and foreshadowing his leadership role.[44]Miracles and Trials of St. Peter

The miracles and trials of St. Peter in the Brancacci Chapel frescoes draw primarily from the Acts of the Apostles, supplemented by apocryphal accounts in texts like the Golden Legend, to depict Peter's exercise of divine authority amid persecution and communal challenges. Masaccio executed several key scenes between approximately 1425 and 1427, emphasizing themes of healing, judgment, and redemption through naturalistic figures and spatial depth. These panels, measuring around 230 by 162 cm each, integrate continuous narratives within unified architectural settings, reflecting Peter's role as Christ's vicar.[45][22] In St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow, Masaccio illustrates Acts 5:15, where Peter's passing shadow restores health to the infirm lined along a Roman street. The fresco shows Peter advancing from the left, his elongated shadow falling centrally over the supplicants, while disciples trail behind; this sequence underscores the unmediated transmission of apostolic power without physical contact. The architectural backdrop, with coffered vaults and receding orthogonals, establishes a coherent perspectival space, innovative for its time.[45][44] Adjacent, The Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias conveys two linked events from Acts 4:32–5:11: Peter and St. John dispensing communal funds to the needy on the left, followed by Ananias collapsing dead on the right after concealing proceeds from a property sale. Masaccio's composition employs a single vanishing point to link the vignettes, with Ananias's dramatic fall—body twisting in agony—conveying instant divine retribution for deceit. The donors' varied expressions and gestures heighten the moral contrast between generosity and hypocrisy.[46][22] The Baptism of the Neophytes portrays Peter baptizing converts in a rocky outdoor setting, symbolizing initiation into the faith; nude figures emerging from water evoke vulnerability and renewal, while bystanders' reluctance highlights communal purity requirements. Masaccio's attention to anatomical volume and wet drapery effects realism in the rite.[22][25] Peter's trials include imprisonment, addressed in Filippino Lippi's later additions around 1481–1485: St. Paul Visiting St. Peter in Prison shows Paul consoling the chained apostle, and The Liberation of St. Peter depicts angelic release, per Acts 12. Masaccio initiated The Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St. Peter Enthroned, where Peter resurrects the prefect's deceased son post-incarceration, as recounted in the Golden Legend; enthroned centrally, Peter receives homage, affirming his papal primacy amid a crowded basilica interior. Lippi completed the upper sections, blending with Masaccio's lower figures to narrate vindication through miracle.[47][22][48]St. Peter's Martyrdom and Legacy

The martyrdom of Saint Peter concludes the fresco cycle in the Brancacci Chapel, depicted in Filippino Lippi's panel Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of St. Peter, executed between 1481 and 1485 on the chapel's altar wall.[22] [49] This fresco integrates two narrative episodes: Peter's confrontation with the sorcerer Simon Magus before Emperor Nero on the right, where Peter's prayer causes Simon's fall, and the saint's inverted crucifixion on the left, symbolizing his deference to Christ's sacrifice by requesting an upside-down execution as he deemed himself unworthy of the same posture.[24] [25] Lippi's composition employs a continuous narrative across the panel, with figures observing both events simultaneously, heightening the dramatic tension of Peter's final trial and execution under Nero's persecution around 64-67 CE, as recorded in early Christian traditions.[50] The inverted cross, central to the left scene, visually reinforces Peter's humility and the inversion of worldly power through divine authority, with executioners nailing his legs while crowds witness the event.[24] In the broader iconographic program of the chapel, Peter's martyrdom encapsulates his legacy as the foundational apostle and first bishop of Rome, entrusted by Christ with the keys to the Kingdom and the shepherding of the faithful, linking human redemption from Original Sin—depicted in the chapel's upper register—to ecclesiastical salvation.[13] The cycle's progression from Peter's calling and miracles to his sacrificial death underscores the causal chain of apostolic witness establishing the Church's enduring authority against heresy and persecution, as Peter's triumph over Simon Magus prefigures the Church's doctrinal victories.[29] This narrative closure, completed decades after Masaccio and Masolino's initial work around 1425, affirms Peter's role in perpetuating Christ's mission, influencing subsequent Renaissance depictions of papal primacy and martyrdom.[51]Layout and Viewing Experience

Spatial Arrangement of the Panels

The fresco panels of the Brancacci Chapel occupy the lateral and altar walls of the small rectangular space (approximately 4.7 meters wide by 6.7 meters long), forming a continuous cycle visible upon entry from the south transept of Santa Maria del Carmine.[1] The side walls each host four rectangular panels in two horizontal registers (upper and lower), each panel measuring roughly 2.5 meters high by 6 meters wide, painted in buon fresco technique to cover the plaster surfaces without frames or strict divisions between adjacent scenes.[29] This grid-like structure on the walls integrates illusionistic architectural elements, such as fictive columns and arches, to unify the composition and direct the viewer's eye toward converging vanishing points calibrated for standing observers below.[1] On the left wall (south wall, facing the altar), the upper register positions Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden to the left (adjacent to the entrance pilaster) and his Tribute Money to the right, juxtaposing the consequences of original sin with Peter's resolution of a fiscal miracle from the Gospel of Matthew (17:24-27).[22] The lower register continues with Masolino's Preaching of Saint Peter on the left and Masaccio's Baptism of the Neophytes on the right, maintaining a left-to-right progression that links doctrinal teaching to sacramental initiation.[29] The right wall (north wall) employs a similar tiered format, with the lower register featuring Masaccio's Saint Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow (left) and Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias (right), emphasizing apostolic power and judgment; the upper register, left incomplete until 1481-1485, contains Filippino Lippi's Disputation with Simon Magus (left) and Crucifixion of Saint Peter (right).[22] [1] The altar wall integrates three principal scenes: Masaccio's Raising of the Son of Theophilus spanning the left side and connecting to the adjacent wall, centered by Saint Peter Enthroned (partly executed by Masaccio and completed by Lippi), flanked on the right by Masolino's Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha.[22] Pilasters and smaller areas on this wall and sides include Lippi's additions, such as Saint Paul Visiting Saint Peter in Prison and Liberation of Saint Peter from Prison, framing the liturgical altar to culminate the narrative in themes of resurrection and martyrdom.[29] Overall, the arrangement supports a didactic viewing sequence—commencing upper left, traversing rightward across tiers, then to the altar—paralleling humanity's fall (upper left) with Peter's redemptive ministry below and beyond, optimized for the chapel's confined scale where light from narrow windows enhances the dramatic chiaroscuro.[1] [22]Original and Reconstructed Perspectives

The frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel were designed with linear perspectives calibrated for viewers standing on the chapel floor in the center of the space, at an approximate eye height of 1.5 to 1.7 meters, allowing coherent spatial illusion across the walls and avoiding distortions from extreme angles.[44] In Masaccio's The Tribute Money, for instance, orthogonals from architectural elements and figures converge on a vanishing point aligned with Christ's head when observed from a distance of about 6 meters from the wall, integrating the three episodes of the narrative into a unified scene that rewards this fixed viewpoint.[52] Similarly, in The Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha, the street recedes toward a vanishing point suited to the same observer position, enhancing the illusion of depth within the chapel's barrel-vaulted confines.[53] This approach marked an innovation over prior Gothic schemes, prioritizing causal realism in light and shadow modulation to match the Carmelite church's natural illumination from side windows.[54] Historical interventions obscured this intended experience: the chapel was whitewashed around 1739 for political reasons tied to the Brancacci family's exile, then partially damaged by the 1771 church fire, leading to overpainting and dimmed tones that flattened perceived perspectives until the 19th-century uncovering.[13] The 1980s restoration, involving solvent cleaning and removal of baroque-era retouchings, revealed the original vibrant pigments—such as azurite blues and vermilion reds—restoring luminosity that amplifies the frescoes' atmospheric depth and viewpoint-specific shadows, as documented in technical analyses of pigment layers and binding media.[55] Post-restoration examinations confirmed that Masaccio's underdrawings (sinopie) align with these perspectives, evidencing premeditated orthogonals for floor-level viewing without later alterations.[56] Modern reconstructions further elucidate the original setup through digital and virtual modeling. The BrancacciPOV project, a 2022 virtual reality prototype developed by Italy's CNR-ISPC, simulates immersion within the fresco surfaces, replicating 15th-century lighting conditions and viewer trajectories to demonstrate how perspectives unify when experienced sequentially from the entrance, countering fragmented modern visits limited to small groups.[57] Photogrammetric surveys from 2020 onward, using laser scanning and hyperspectral imaging, have reconstructed the chapel's pre-fire geometry, verifying that Masolino and Lippi's contributions maintain compatible vanishing points despite stylistic variances, thus preserving the cycle's holistic viewpoint.[58] These tools highlight discrepancies in earlier interpretations, such as overstated distortions from off-axis viewing, attributing them to degraded surfaces rather than design flaws.[29]Artistic Significance and Innovations

Breakthroughs in Perspective and Realism

Masaccio's contributions to the Brancacci Chapel frescoes, executed between approximately 1424 and 1428, introduced linear perspective as a systematic method for representing spatial depth, building on Filippo Brunelleschi's optical experiments conducted in the early 1420s.[59] In The Tribute Money, dated to circa 1425–1427, this manifests through a centralized vanishing point aligned with Christ's head, which organizes orthogonals converging on the architectural elements and figures, thereby unifying three temporally distinct narrative episodes—Christ's directive to Peter, the tribute payment, and the coin's retrieval from the fish—within a single, illusionistic space.[44] [52] Atmospheric perspective further enhances depth in the background landscape, with receding forms rendered in cooler tones and diminished detail to simulate aerial diffusion.[44] These perspectival techniques complemented Masaccio's pursuit of realism in figure depiction, where forms achieve three-dimensional volume through precise anatomical structure and modulated shading via chiaroscuro, departing from the flatter, more stylized figures of predecessors like Giotto di Bondone.[20] Figures exhibit weighted stances, with contrapposto-like shifts in balance and foreshortening in limbs to convey dynamic movement and corporeality, informed by direct observation of the human body rather than idealized medieval schemas.[21] In The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve's musculature and skeletal proportions reflect empirical anatomical knowledge, while their gestures—Adam's anguished cover of his face and Eve's wailing posture—capture raw emotional immediacy, grounding biblical narrative in observable human psychology.[60] Such innovations prioritized causal optical effects and proportional accuracy, establishing painting as a rational, measurable enterprise that mirrored empirical reality, influencing subsequent Renaissance developments in spatial and figural representation.[20][21]Light, Shadow, and Human Anatomy

Masaccio's frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, executed between 1424 and 1427, introduced a pioneering application of chiaroscuro, employing contrasts of light and shadow to impart three-dimensional volume to figures and architecture. This technique modeled forms with gradations from light to dark, departing from the flat, uniform illumination of earlier Italian painting, and created a sense of depth and solidity in the human body.[60][61] In scenes such as The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, shadows cast by Adam and Eve's bodies align with a single light source approximating the chapel's actual window, enhancing spatial coherence and realism.[61][14] The consistent directionality of light across panels unified the narrative cycle, simulating natural illumination that interacts dynamically with forms. For instance, in St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow, the apostle's elongated shadow becomes a miraculous agent, rendered with precise tonal modulation to convey both narrative symbolism and optical verisimilitude. This approach not only heightened dramatic tension but also grounded supernatural events in observable physical principles, influencing subsequent Renaissance depictions of light as a causal force in composition.[44][14] Complementing these optical innovations, Masaccio's treatment of human anatomy emphasized anatomical accuracy and emotional expressivity, drawing on classical precedents and contemporary dissections to depict musculature, posture, and proportion with unprecedented fidelity. Figures possess weighty, monumental solidity, their limbs and torsos sculpted through shadow to reveal underlying skeletal structure and muscle tension, as seen in the strained, nude forms of Adam and Eve conveying shame and despair through contorted gestures and facial contortions.[62][61] This naturalistic rendering marked a shift from symbolic to corporeal humanity, prioritizing observable bodily mechanics over stylized idealization.[60] In The Tribute Money, anatomical precision extends to group dynamics, with figures exhibiting varied poses that demonstrate torsion, balance, and interaction, their drapery adhering to and revealing body contours under modulated light. Masaccio's method integrated light, shadow, and anatomy to achieve a causal realism, where illumination logically dictates form perception, establishing benchmarks for volumetric depiction that persisted in later masters like Michelangelo.[44][63]Influence and Reception

Impact on Renaissance Masters

The Brancacci Chapel's frescoes, executed primarily by Masaccio between 1425 and 1427, exerted profound influence on later Renaissance artists through their pioneering use of linear perspective, volumetric figures, and naturalistic light effects. Michelangelo Buonarroti, born in 1475, visited the chapel repeatedly in the early 1490s as a young apprentice, sketching and copying Masaccio's compositions to master anatomical precision and emotional gravitas in human forms, techniques evident in his later works like the *Sistine Chapel* ceiling painted from 1508 to 1512.[14][64] Sandro Botticelli and Domenico Ghirlandaio also studied the chapel's panels, adopting Masaccio's emphasis on spatial depth and narrative clarity while infusing their own styles with greater lyricism and idealization, as seen in Botticelli's mythological scenes from the 1480s.[65] Filippino Lippi, who completed the unfinished sections between 1481 and 1485, directly engaged with Masaccio's innovations, bridging early and High Renaissance developments.[66] The chapel functioned as an informal academy for Florentine painters, with artists like Lippo Lippi and Andrea del Castagno drawing from its realistic modeling of drapery and shadow to advance figural monumentality, fundamentally altering the trajectory of Tuscan art toward greater empirical observation of the natural world.[61] This emulation underscores Masaccio's causal role in shifting painting from medieval symbolism to Renaissance humanism grounded in observable reality.[44]Historical Viewership and Study

The frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel gained immediate renown in the 15th century, serving as a primary study site for Florentine and visiting artists who copied and analyzed their innovative techniques in perspective, anatomy, and light. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, expanded 1568), described the chapel as the "cappella degli studiosi" (chapel of studies), emphasizing that it was visited by virtually all practitioners of painting from Masaccio's era through the mid-16th century, who treated it as a foundational "school of the world" for mastering naturalistic representation.[67] Michelangelo Buonarroti, as a young artist in the 1490s, dedicated months to sketching Masaccio's figures, particularly in scenes like The Tribute Money and The Expulsion from Paradise, which informed his later works such as the Sistine Chapel ceiling; surviving drawings, including one after Saint Peter, attest to this direct engagement.[68][69] Other major figures, including Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Sandro Botticelli, and Filippino Lippi (who completed the cycle in 1481–1485), similarly studied and replicated the compositions, with Vasari noting Leonardo's particular admiration for Masaccio's lifelike figures.[68][1] Access required permission from the Carmelite monks of Santa Maria del Carmine, leading artists to queue for entry, a practice documented in contemporary accounts and reflected in the volume of extant copies from the 15th and 16th centuries.[1] Into the 16th and 17th centuries, the chapel continued to draw homage from painters like Andrea del Sarto and Pontormo, though viewership waned as Renaissance innovations proliferated elsewhere in Florence. The 1771 fire that gutted the adjacent church spared the chapel but prompted protective whitewashing, obscuring the frescoes until partial cleanings in the 19th century revived scholarly interest; 19th-century copies, such as Cesare Mariannecci's watercolors after key scenes, preserved details for further study amid these interventions.[70] By the early 20th century, art historians like those at Harvard's Villa I Tatti began systematic analysis of its patronage and iconography, building on Vasari's framework to contextualize its role in transmitting early Renaissance naturalism.[71]Conservation History

Early Repairs and Interruptions

The frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel were begun in 1425 by Masolino da Panicale, who was soon joined by the younger Masaccio; their collaborative work on scenes from the life of Saint Peter continued until Masaccio's death in Rome in autumn 1428, after which Masolino also departed for other commissions, leaving the cycle incomplete.[14][13] This interruption spanned over five decades, during which the unfinished portions remained unpainted, and the chapel saw limited use amid the Brancacci family's declining fortunes.[72] Felice Brancacci's exile in 1435—stemming from his anti-Medici political alignments—and his formal declaration as a rebel in 1458 prompted alterations to the frescoes, including plastering over family coats of arms and donor portraits to efface associations with the disgraced patron.[13][73] Work resumed only in the 1480s under Filippino Lippi, who removed layers of plaster to expose the earlier frescoes, integrated his own completions, and addressed nascent damages from exposure and neglect, effectively serving as the first documented intervention to restore visibility and coherence.[2][74] A further restoration occurred at the end of the 16th century, likely involving cleaning and minor repainting to counteract accumulating grime and flaking, though details remain sparse due to limited contemporary records.[2] By the mid-18th century, Baroque-era modifications in 1746–1748 included the construction of a new lower vault, necessitating the detachment and reattachment of Masolino's ceiling frescoes and adjacent upper panels, which introduced new structural stresses and overpainting that obscured original pigments.[75][74] These early efforts, while preserving the works against immediate loss, often prioritized aesthetic adaptation over fidelity, setting the stage for later degradations culminating in the 1771 fire.[76]Major Restorations: 1771 Fire and Beyond

On January 29, 1771, a fire ravaged the Basilica di Santa Maria del Carmine, destroying much of the church's interior and many chapels, though the Brancacci Chapel sustained comparatively limited damage, with the frescoes affected primarily by heat-induced discoloration and plaster detachment rather than total loss.[77][23] The blaze spared the structural integrity of the chapel walls, allowing for subsequent salvage and repair of the Renaissance fresco cycle by Masaccio, Masolino da Panicale, and Filippino Lippi.[2] Post-fire reconstruction of the chapel and church commenced promptly, incorporating late-Baroque stylistic elements under the direction of architect Giuseppe Ruggieri, with major works concluding by the late 1770s.[22] A new altar was installed during this phase, altering the chapel's original layout and partially obscuring lower fresco sections until later removals.[77] In 1780, following the Brancacci family's financial ruin and flight to France amid Medici-era political shifts, the chapel was acquired by the Riccardi family, who funded further renovations to integrate it with the rebuilt church, including decorative enhancements that preserved but did not fully restore the frescoes' original vibrancy.[2][72] Throughout the 19th century, the frescoes endured neglect, accumulating grime and soot from environmental exposure and limited maintenance within the Carmelite complex.[64] A significant cleaning campaign in 1904 removed surface accumulations, revealing enhanced color tones and preparatory sinopia underdrawings, though it employed methods now critiqued for potential over-aggressiveness in solvent use.[64] These efforts marked the last major intervention before mid-20th-century assessments, stabilizing the artworks amid ongoing structural vulnerabilities in the post-fire church fabric.[78]1980s Cleaning and Revelations

In the early 1980s, the Brancacci Chapel underwent a comprehensive restoration project directed by conservators Umberto Baldini and Ornella Casazza, with the chapel closing to the public around 1981 to facilitate detailed examination and cleaning of the frescoes.[79] [18] The effort, spanning nine years until 1990, addressed accumulations of soot from votive lamps, varnish layers, atmospheric pollutants, and residues from prior interventions, which had obscured the original pigments and surfaces since the 15th century.[79] [39] The cleaning process employed solvent-based methods and mechanical removal to strip these overlays, unveiling brighter original colors, sharper tonal contrasts, and enhanced visibility of linear perspective and chiaroscuro effects in Masaccio's contributions, such as the volumetric modeling in figures like those in The Tribute Money and The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.[79] [39] Conservation teams also detached sinopias—red ochre underdrawings—from two lost frescoes on the chapel's entrance arch, revealing preparatory sketches that illuminated the artists' initial compositional plans and execution techniques for the Life of Saint Peter cycle.[18] These interventions confirmed the frescoes' technical sophistication, including Masaccio's experimental use of light sources aligned with real chapel windows and anatomical precision, while exposing residual damages from earlier events like the 1771 fire and 1966 flood.[79] Post-restoration analysis noted some loss of surface patina and chromatic depth due to irreversible prior alterations, yet the overall disclosure of unaltered pigment layers substantiated the chapel's status as a pivotal early Renaissance site, influencing subsequent scholarly attributions and iconographic studies.[55] The chapel reopened on June 8, 1990, enabling direct observation of these rediscovered details by researchers and visitors.[79]Recent Technological Advances (2000s–2025)

In preparation for and during the 2020–2024 restoration of the Brancacci Chapel frescoes, noninvasive high-definition imaging techniques were employed, including examinations under visible, raking, ultraviolet, and infrared light, to identify artists' original methods, materials, and deterioration patterns without damaging the surfaces.[72] These diagnostics, conducted by collaborators such as the Opificio delle Pietre Dure and Italy's National Research Council (CNR), revealed subtle degradation phenomena and informed targeted cleaning and stabilization efforts, enabling the project to address issues undetected in prior 1980s interventions.[72] Geophysical surveys using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) with 900 MHz and 2000 MHz antennas provided non-destructive structural analysis of the chapel walls in 2023, mapping 17 voids, 24 fractures, and detachments via 3D time-slice processing and dielectric permittivity assessments.[80] This revealed wall thicknesses of approximately 0.6 meters, multi-layered plaster (0.03–0.04 meters thick), and moisture content of 4–6% from historical gypsum injections, guiding preventive measures against further fresco detachment and informing long-term monitoring protocols.[80] Complementary 3D surveying integrated laser scanning and photogrammetry to generate high-fidelity models and real-time simulations of the chapel's interior, supporting conservation planning by visualizing surface irregularities and enabling virtual reconstructions for scholarly analysis.[81] These multimodal approaches, combining optical and radar data, enhanced precision in defect localization and material assessment compared to traditional methods, with outcomes including a Web3D application for public communication and ongoing preservation strategies presented at a 2025 conference.[72][81]Scholarly Debates

Authorship Attributions and Disputes

The Brancacci Chapel fresco cycle, commissioned by Felice Brancacci around 1422 and initiated in 1424–1425, involved primary contributions from Masolino da Panicale and Masaccio until interruptions in 1427–1428, when Masaccio traveled to Rome and died there at age 27, leaving multiple scenes unfinished; Masolino had already departed for other commissions, including in Hungary.[1] Filippino Lippi resumed and completed the work from 1481 to 1485, integrating new scenes and overpainting sections to harmonize the ensemble.[22] Early attributions, as recorded by Giorgio Vasari in his 1550 Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori, predominantly credited Masaccio with the cycle's innovations, downplaying Masolino as a mere associate whose style lacked the younger artist's revolutionary naturalism and perspective. This view persisted into the 19th century but was challenged by 20th-century scholars through comparative stylistic analysis, restoring Masolino's role in scenes emphasizing graceful figures and International Gothic elements, such as Original Sin and Temptation of Adam and Eve on the chapel's upper left wall.[1] Masaccio's undisputed panels, including Expulsion from Paradise and The Tribute Money, demonstrate stark contrasts in volumetric modeling and emotional depth, underscoring their divided labor despite close collaboration.[44] Specific disputes center on hybrid or transitional elements. In the Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha (upper right wall), traditionally assigned to Masolino for its fluid compositions, Roberto Longhi's 1940 analysis reattributed the head of Christ to Masolino based on facial typology and execution, countering broader ascriptions of the scene to Masaccio alone; subsequent scholars have partially accepted this, though consensus remains divided due to shared workshop practices.[82] Similarly, the Temptation panel shows stylistic inconsistencies, with the serpent and tree potentially reflecting Masaccio's intervention in Masolino's design, as evidenced by underdrawing variations revealed in post-1980s technical studies.[55] Lippi's completions, particularly in the lower register, have sparked debate over emulation versus invention; the St. Peter Enthroned scene, long misattributed to Masaccio for its volumetric figures, exemplifies Lippi's deliberate mimicry of his predecessor's techniques, blending unfinished Raising of the Son of Theophilus underlayers with new additions, as confirmed by infrared examinations distinguishing preparatory sinopias.[24] While some historians, like Frank Jewett Mather Jr. in 1944, questioned the visibility of surviving Masolino elements due to overpainting and damage, empirical evidence from conservation— including pigment analysis and stratigraphy—supports differentiated hands, affirming the cycle's layered authorship without resolving all ambiguities in collaborative zones.[83]Interpretations of Patron Intent and Iconography