Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Malachite

View on Wikipedia| Malachite | |

|---|---|

Malachite from the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate mineral |

| Formula | Cu2CO3(OH)2 |

| IMA symbol | Mlc[1] |

| Strunz classification | 5.BA.10 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/a |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 221.1 g/mol |

| Color | Bright green, dark green, blackish green, with crystals deeper shades of green, even very dark to nearly black commonly banded in masses; green to yellowish green in transmitted light |

| Crystal habit | Massive, botryoidal, stalactitic, crystals are acicular to tabular prismatic |

| Twinning | Common as contact or penetration twins on {100} and {201}. Polysynthetic twinning also present. |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {201} fair on {010} |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3.5–4 |

| Luster | Adamantine to vitreous; silky if fibrous; dull to earthy if massive |

| Streak | light green |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 3.6–4 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (–) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.655 nβ = 1.875 nγ = 1.909 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.254 |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Malachite (/ˈmæl.əˌkaɪt/) is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the formula Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often forms botryoidal, fibrous, or stalagmitic masses, in fractures and deep, underground spaces, where the water table and hydrothermal fluids provide the means for chemical precipitation. Individual crystals are rare, but occur as slender to acicular prisms. Pseudomorphs after more tabular or blocky azurite crystals also occur.[5]

Etymology and history

[edit]

The stone's name derives (via Latin: molochītis, Middle French: melochite, and Middle English melochites) from Greek Μολοχίτης λίθος molochites lithos, "mallow-green stone", from μολόχη molochē, variant of μαλάχη malāchē, "mallow".[6] The mineral was given this name due to its resemblance to the leaves of the mallow plant.[7] Copper (Cu2+) gives malachite its green color.[8]

Malachite was mined from deposits near the Isthmus of Suez and the Sinai as early as 4000 BCE.[9]

It was extensively mined at the Great Orme Mines in Britain 3,800 years ago, using stone and bone tools. Archaeological evidence indicates that mining activity ended c. 600 BCE, with up to 1,760 tonnes of copper being produced from the mined malachite.[10][11]

Archaeological evidence indicates that the mineral has been mined and smelted to obtain copper at Timna Valley in contemporary Israel for more than 3,000 years.[12] Since then, malachite has been used as both an ornamental stone and as a gemstone.

The use of azurite and malachite as copper ore indicators led indirectly to the name of the element nickel in the English language. Nickeline, a principal ore of nickel that is also known as niccolite, weathers at the surface into a green mineral (annabergite) that resembles malachite. This resemblance resulted in occasional attempts to smelt nickeline in the belief that it was copper ore, but such attempts always ended in failure due to high smelting temperatures needed to reduce nickel. In Germany this deceptive mineral came to be known as kupfernickel, literally "copper demon." The Swedish alchemist Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (who had been trained by Georg Brandt, the discoverer of the nickel-like metal cobalt) realized that there was probably a new metal hiding within the kupfernickel ore, and in 1751 he succeeded in smelting kupfernickel to produce a previously unknown (except in certain meteorites) silvery white, iron-like metal. Logically, Cronstedt named his new metal after the nickel part of kupfernickel.

Occurrence

[edit]

Malachite often results from the supergene weathering and oxidation of primary sulfidic copper ores, and is often found with azurite (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2), goethite, and calcite. Except for its vibrant green color, the properties of malachite are similar to those of azurite and aggregates of the two minerals occur frequently. Malachite is more common than azurite and is typically associated with copper deposits around limestones, the source of the carbonate.

Large quantities of malachite have been mined in the Urals, Russia. Ural malachite is not being mined as of 2006[update],[13] but G.N Vertushkova reports the possible discovery of new deposits of malachite in the Urals.[14] It is found worldwide including in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Gabon; Zambia; Tsumeb, Namibia; Mexico; Broken Hill, New South Wales; Burra, South Australia; Lyon, France; Timna Valley, Israel; and the Southwestern United States, most notably in Arizona.[15]

Anthropogenic malachite was historically believed to be the primary component of the patina which forms on copper and copper alloy structures exposed to open-air weathering; however, atmospheric sources of sulfate and chloride (such as air pollution or sea winds) typically favour the formation of brochantite or atacamite.[16] Malachite can also be produced synthetically, in which case it is referred to as basic copper carbonate or green verditer.

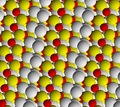

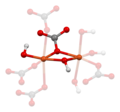

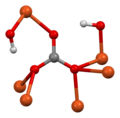

Structure

[edit]Malachite crystallizes in the monoclinic system. The structure consists of chains of alternating Cu2+ ions and OH− ions, with a net positive charge, woven between isolated triangular CO32− ions. Thus each copper ion is conjugated to two hydroxyl ions and two carbonate ions; each hydroxyl ion is conjugated with two copper ions; and each carbonate ion is conjugated with six copper ions.[17][18]

-

View along c axis of the crystal structure of malachite

-

View along a axis of malachite crystal structure

-

View along b axis of malachite crystal structure

-

Unit cell of malachite

-

Formula unit and its coordination environment

-

Coordination environment of copper #1

-

Coordination environment of copper #2

-

Coordination environment of carbonate

-

Coordination environment of hydroxide #1

-

Coordination environment of hydroxide #2

Use

[edit]

Malachite was used as a mineral pigment in green paints from antiquity until c. 1800.[20] The pigment is moderately lightfast, sensitive to acids, and varying in color. This natural form of green pigment has been replaced by its synthetic form, verditer, among other synthetic greens.

Malachite is also used for decorative purposes, such as in wands and the Malachite Room in the Hermitage Museum,[21] which features a huge malachite vase, and the Malachite Room in Castillo de Chapultepec in Mexico City.[22] Russian Tsars obtained malachite for decorating their castles, panelling the walls, and for beautiful inlaid works.[23] Another example is the Demidov Vase, part of the former Demidov family collection, and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[24] "The Tazza", a large malachite vase, one of the largest pieces of malachite in North America and a gift from Tsar Nicholas II, stands as the focal point in the centre of the room of Linda Hall Library. In the time of Tsar Nicolas I decorative pieces with malachite were among the most popular diplomatic gifts.[25] It was used in China as far back as the Eastern Zhou period.[26] The base of FIFA World Cup Trophy has two layers of malachite.

Symbolism and superstitions

[edit]A 17th-century Spanish superstition held that having a child wear a lozenge of malachite would help them sleep, and keep evil spirits at bay.[27] Marbodus recommended malachite as a talisman for young people because of its protective qualities and its ability to help with sleep.[28] It has also historically been worn for protection from lightning and contagious diseases and for health, success, and constancy in the affections.[28] During the Middle Ages it was customary to wear it engraved with a figure or symbol of the Sun to maintain health and to avert depression to which Capricorns were considered vulnerable.[28]

In ancient Egypt the colour green (wadj) was associated with death and the power of resurrection as well as new life and fertility. Ancient Egyptians believed that the afterlife contained an eternal paradise, referred to as the "Field of Malachite", which resembled their lives but with no pain or suffering.[29] During these times, the green pigment made from malachite was often used for eye preparations during the burial process. These preparations were an essential tool in the funerary equipment, even in modest burials.[30]

Ore uses

[edit]

Simple methods of copper ore extraction from malachite involved thermodynamic processes such as smelting.[31] This reaction involves the addition of heat and a carbon, causing the carbonate to decompose leaving copper oxide and an additional carbon source such as coal converts the copper oxide into copper metal.[31][32]

The basic word equation for this reaction is:

Copper carbonate + heat → carbon dioxide + copper oxide (color changes from green to black).[31][32]

Copper oxide + carbon → carbon dioxide + copper (color change from black to copper colored).[31][32]

Malachite is a low grade copper ore, however, due to increase demand for metals, more economic processing such as hydrometallurgical methods (using aqueous solutions such as sulfuric acid) are being used as malachite is readily soluble in dilute acids.[33][34] Sulfuric acid is the most common leaching agent for copper oxide ores like malachite and eliminates the need for smelting processes.[35]

The chemical equation for sulfuric acid leaching of copper ore from malachite is as follows:[35]

| + → + + | Reaction 1 |

Health and environmental concerns

[edit]Mining for malachite for ornamental or copper ore purposes involves open-pit mining or underground mining depending on the grade of the ore deposits.[36] Open-pit and underground mining practices can cause environmental degradation through habitat and biodiversity loss.[37][38] Acid mine drainage can contaminate water and food sources to negatively impact human health if improperly managed or if leaks from tailing ponds occur.[38][39] The risk of health and environmental impacts of both traditional metallurgy and newer methods of hydrometallurgy are both significant,[38] however, water conservation and waste management practices for hydrometallurgy processes for ore extraction, such as for malachite, are stricter and relatively more sustainable.[40] New research is also being conducted on better alternatives to methods such as sulfuric acid leaching which has high environmental impacts, even under hydrometallurgy regulation standards and innovation.[35]

Gallery

[edit]-

Slice through a double stalactite, from Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size 5.9 × 3.9 × 0.7 cm.

-

Malachite stalactites (to 9 cm height), from Kasompi Mine, Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size: 21.6×16.0×11.9 cm.

-

Sample of malachite found at Kaluku Luku Mine, Lubumbashi, Shaba, Congo

-

Vase in malachite in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

-

Malachite, image taken under a stereoscopic microscope

-

British calendar, 1851, gilt bronze and malachite, height: 20.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Malachite at Kaleideum Children's Museum

-

Elephant carved from malachite. Length 11 cm.

-

A polished slice of malachite through three intergrown stalactites with bulls-eye banding

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (2003). "Malachite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. V (Borates, Carbonates, Sulfates). Chantilly, Virginia: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209740.

- ^ Malachite. Webmineral

- ^ a b Malachite. Mindat

- ^ Malachite, Dictionary.com

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "malachite". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Minerals Colored by Metal Ions". minerals.gps.caltech.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Susarla, S.M (2016). "The colourful history of malachite green: from ancient Egypt to modern surgery". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 46 (3): 401–403. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.022. PMID 27771151.

- ^ Johnson, Ben, ed. (2014). "The Great Orme Mines". Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Ruggeri, Amanda (21 April 2016). "The Ancient Copper Mines Dug By Bronze Age Children". BBC. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Parr, Peter J. (1974). "Review of 'Timma: Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines' by Beno Rothenberg Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 223–224

- ^ Куда делись символы России? Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Argumenty i Fakty (24 May 2006)

- ^ Somin, L. M. Тайны седого Урала. Малахит Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine. oldrushistory.ru

- ^ Mindat map with over 8500 locations. mindat.org

- ^ W. H. J. Vernon (1934). "Basic copper carbonate and green patina". J. Chem. Soc.: 1853. doi:10.1039/JR9340001853.

- ^ Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. (1993). Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) (21st ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 417. ISBN 047157452X.

- ^ "Malachite". American Mineralogical Crystal Structure Database. Department of Geology, University of Arizona. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "The Red Queen and Her Sisters: Women of Power in Golden Kingdoms". www.metmuseum.org. 7 March 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Gettens, R.J. and Fitzhugh, E. W. (1993) "Malachite and Green Verditer", pp. 183–202 in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0894682601

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2011). "Малахитовые залы Петербурга, России, Европы... / Malachite salon of St.-Petersburg, Russia, Europe..." // Блистательный Петербург. Роль архитекторов XIX века в создании неповторимого облика города. Материалы научно-практической конференции. Кафедра. Сб. науч. Ст. – СПб.: Государственный музей-памятник «Исаакиевский собор», 2011. – С. 23-49.

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2013). "La produzione in malachite dei Demidov: sulle trace degli oggetti alla prima esposizione universale / I Demidoff fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e prestigio di une famiglia in Europa dal XVIII al XX secolo. – P. 151-176, 9 tav". // I Demidoff Fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e Prestigio di Une Famiglia in Europa Dal XVIII al XX Secolo. A Cura di Lucia Tonini. Cultura e Memoria, Vol. 50. – Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2013.

- ^ Schumann, Walter (1977). Minerals of the World. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. p. 176.

- ^ Monumental vase lapidary work: early 19th century; pedestal and mounts: 1819 Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Будрина, Людмила (2020). Малахитовая дипломатия. Екатеринбург: Кабинетный ученый. p. 208. ISBN 978-5-6044025-1-1.

- ^ Langhals, Heinz; Bathelt, Daniela (1 December 2003). "The Restoration of the Largest Archaelogical Discovery—a Chemical Problem: Conservation of the Polychromy of the Chinese Terracotta Army in Lintong". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 42 (46): 5676–5681. doi:10.1002/anie.200301633. PMID 14661198.

- ^ The Illustrated Book of Signs and Symbols by Miranda Bruce-Mitford, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 1996, p. 41

- ^ a b c The Book of Talismans, Amulets and Zodiacal Gems, by William Thomas and Kate Pavitt, [1922], p. 254

- ^ Hill, J (2010). "Meaning of green in ancient Egypt". Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ^ do Sameiro Barroso, Maria (June 2017). "Malachite, the Healing Gem of Green Nature". Vesalius: Acta Internationales Historiae Medicinae. 23: 101, 102.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Cris E.; Yee, Gordon T.; Eddleton, Jeannine E. (2004-12-01). "Copper Metal from Malachite circa 4000 B.C.E.". Journal of Chemical Education. 81 (12): 1777. Bibcode:2004JChEd..81.1777J. doi:10.1021/ed081p1777. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c Day, Jo; Kobik, Maggie (2019-09-30), "Reconstructing a Bronze Age Kiln from Priniatikos Pyrgos, Crete", Experimental Archaeology: Making, Understanding, Story-telling, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, pp. 63–72, doi:10.2307/j.ctvpmw4g8.11, ISBN 978-1-78969-320-1, S2CID 210629355, retrieved 2021-02-25

- ^ Ata, O. N.; Yalap, H. (2007-06-01). "Optimization of Copper Leaching from Ore Containing Malachite". Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly. 46 (2): 107–114. Bibcode:2007CaMQ...46..107A. doi:10.1179/cmq.2007.46.2.107. ISSN 0008-4433. S2CID 98163205.

- ^ "Malachite". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ a b c Shabani, M. A.; Irannajad, M.; Azadmehr, A. R. (2012-09-01). "Investigation on leaching of malachite by citric acid". International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy, and Materials. 19 (9): 782–786. Bibcode:2012IJMMM..19..782S. doi:10.1007/s12613-012-0628-9. ISSN 1869-103X. S2CID 96128268.

- ^ "Malachite". www.mine-engineer.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Monjezi, M.; Shahriar, K.; Dehghani, H.; Samimi Namin, F. (2009-07-01). "Environmental impact assessment of open pit mining in Iran". Environmental Geology. 58 (1): 205–216. Bibcode:2009EnGeo..58..205M. doi:10.1007/s00254-008-1509-4. ISSN 1432-0495. S2CID 128616763.

- ^ a b c Salomons, W. (1995-01-01). "Environmental impact of metals derived from mining activities: Processes, predictions, prevention". Journal of Geochemical Exploration. Heavy Metal Aspects of Mining Pollution and Its Remediation. 52 (1): 5–23. Bibcode:1995JCExp..52....5S. doi:10.1016/0375-6742(94)00039-E. ISSN 0375-6742.

- ^ "Environmental Impact of Sulfuric Acid Leaching". www.savethesantacruzaquifer.info. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Conard, Bruce R. (1992-06-01). "The role of hydrometallurgy in achieving sustainable development". Hydrometallurgy. Hydrometallurgy, Theory and Practice Proceedings of the Ernest Peters International Symposium. Part B. 30 (1): 1–28. Bibcode:1992HydMe..30....1C. doi:10.1016/0304-386X(92)90074-A. ISSN 0304-386X.