Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

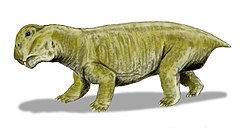

Bulbasaurus

View on Wikipedia

| Bulbasaurus Temporal range: Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Photograph and diagram of holotype skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Family: | †Geikiidae |

| Genus: | †Bulbasaurus Kammerer & Smith, 2017 |

| Type species | |

| Bulbasaurus phylloxyron Kammerer & Smith, 2017

| |

Bulbasaurus (meaning "bulbous reptile") is an extinct genus of dicynodont that is known from the Lopingian epoch of the Late Permian period of what is now South Africa, containing the type and only species B. phylloxyron. It was formerly considered as belonging to Tropidostoma; however, due to numerous differences from Tropidostoma in terms of skull morphology and size, it has been reclassified the earliest known member of the family Geikiidae, and the only member of the group known from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone. Within the Geikiidae, it has been placed close to Aulacephalodon, although a more basal position is not implausible.

Bulbasaurus was ostensibly not directly named after the Pokémon Bulbasaur, but rather after its nasal bosses, which are unusually bulbous among geikiids; however, the describers noted that the similarity in name "may not be entirely coincidental." Additionally, the specific name of the type species means "leaf razor", which is most directly a reference to its keratin-covered jaws. Other distinguishing characteristics of Bulbasaurus among the geikiids include the hook-like beak, very large tusks, and absence of bossing on the prefrontal bone.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

The holotype specimen of Bulbasaurus was found by Roger M.H. Smith in the Vredelus locality, which is located at an altitude of 1,445 metres (4,741 ft), in the district of Fraserburg, Northern Cape, South Africa. This locality is part of what is known as the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone, which belongs to the Lopingian (upper Permian) Hoedemaker Member of the Middle Teekloof Formation. The Tropidostoma AZ is named after the oudenodontid Tropidostoma, which occurs commonly at the site. The holotype itself, which is catalogued as SAM-PK-K11235, is a partially complete skull that is missing the left subtemporal and both postorbital bars. It was discovered lying right-side-up in a bed of grey siltstone with embedded micrite nodules, and there were no associated remains from the rest of the skeleton.[1] "Head-only" preservation is common in therapsid fossils of the Hoedemaker Member, because the specimens were probably left out in the open and became disarticulated before being rapidly buried by flash floods.[2]

Other referred specimens include the nearly-complete skull CGP/1/938 (from the Wilgerbosch Kloof locality in Fraserburg), the complete skull CGP/1/949 (also from Wilgerbosch Kloof), the complete skull with associated lower jaws and postcranial remains CGP/1/970 (from the Blaauwkrans locality in Beaufort West, Western Cape), the complete but crushed skull CGP/1/2263 (locality unknown), the crushed skull with lower jaws SAM-PK-K10106 (from the Paalhuisberg locality in Beaufort West), and the complete juvenile skull with lower laws SAM-PK-K10587 (from the Doornhoek locality in Beaufort West). All of these specimens are either held at the Iziko Museums in Cape Town or the Council for Geoscience in Praetoria. Before being referred to the new genus Bulbasaurus, they were initially treated as specimens of Tropidostoma in collections.[1]

Bulbasaurus was described by Christian Kammerer and Smith in 2017. The description states that the generic name combines the Latin bulbus, referring to the very large and bulbous nasal bosses, with the common suffix -saurus. As for the specific name phylloxyron, meaning literally "leaf razor", it is derived from the Greek phyllos and xyron, and apparently refers to the keratinous covering on the premaxilla, maxilla, and palate that would have been used to shear plant material.[1] Thus, as published, the name of Bulbasaurus does not directly refer to Pokémon, or specifically the similarly-named Bulbasaur. However, Kammerer noted that "if one wished to read between the lines concerning certain similarities, I wouldn't stop them",[3] and later added that "similarities between this species and certain other squat, tusked quadrupeds may not be entirely coincidental."[4]

Description

[edit]Premaxilla, maxilla, and palate

[edit]

At the front of the upper jaw of Bulbasaurus, the tips of the fused premaxillae are strongly hook-like, much more so than Tropidostoma and other dicynodonts[1] but not as much as Dinanomodon.[5] Also unlike Tropidostoma, the flattened front face of the premaxillae bear a tall, narrow, prominent ridge; Aulacephalodon also has a similar ridge, albeit broader and not as sharp. The back of the premaxillae narrow and extend between the roughened bosses on the nasal bones. Viewed from underneath, the bone is roughly pentagonal; the bottom surface bears two ridges near the front, as well as an additional ridge extending backward from where the two forward ridges end, which gradually becomes taller and wider. These ridges are separated by depressions in the bone of roughly equal depth, which is like other geikiids but unlike Tropidostoma. At the outer extremities of the premaxillae, low and roughened ridges are located near the base of the tusks.[1]

Further back on the interior of the upper jaw, the palatine bones are exposed as a palatine pad, which is very roughened and would have been covered in keratin, although the portion where they contact the premaxillae is smooth and sloping. The back portion of the palatines are thinner than the rest of the bone, but it is still thicker than that of either Tropidostoma or Oudenodon, instead resembling Aulacephalodon more closely. The pterygoid bones are robust in contrast to Tropidostoma, and bear ridges that converge into a tall, blade-like process known as the crista oesophagea. The pterygoids also project outwards in rod-like structures to meet the quadrate bones.[1]

Compared to other dicynodonts, the maxillary tusk of Bulbasaurus was massive; the holotype skull, which is 14 cm (5.5 in) long, has a 1.9 cm (0.75 in) tusk diameter. Only Aulacephalodon has comparably large tusks proportionally, but these belong to adult specimens much larger than Bulbasaurus (in juveniles the size of Bulbasaurus, the tusks are still erupting).[6] The root of the tusk bulges outwards from the surface of the maxilla due to its large size. Extensive pitting on the surface of the maxilla is suggestive of some kind of keratinous covering, which has also been inferred for other dicynodonts.[7] Unlike other geikiids and most other cryptodontian dicynodonts, there is no ridge behind the tusk, although mature Aulacephalodon also lack this ridge.[1]

Nasal and orbital rim

[edit]

The nasal bones, which form the roof the snout, bear a pair of enlarged bosses of bone as in other cryptodontians.[8] In contrast to the small, oval-shaped, relatively narrow, and smooth-textured bosses of Tropidostoma, the roughened bosses of Bulbasaurus are very large and nearly form a single continuous boss (although a narrow strip of the premaxilla extends backwards between the bosses). Aulacephalodon and Pelanomodon also have large and roughened bosses, but they are separated in part by the nasals. At the back of the bosses, a slight indentation wrapping around the top and sides of the skull separates them from the eye socket, typical of cryptodontians except for Odontocyclops.[9] The suture between the nasals and the frontal bones is slightly raised relative to the rest of the skull; the same raised suture is also seen in Aulacephalodon and Pelanomodon.[1]

Typical of geikiids, the interorbital region between the eyes was quite broad. The lacrimal bones, prefrontal bones, frontal bones, and jugal bones form the margin of the eye socket, with the portion comprised by the lacrimals having an orbital ridge that is better-developed and more raised. Unlike other cryptodontians, there is no evidence of a second set of bosses on the prefrontals, although their surfaces are somewhat thickened. A relatively deep midline depression (mildly developed in Tropidostoma and Oudenodon, but absent in other geikiids) is visible on the frontals, which are situated largely between the eyes and form roughened edges where they contributes to the rims of the eye sockets. There appears to be no separation of the postfrontal bones from the frontals, which is probably an adult characteristic as in Aulacephalodon. The elongate jugals form part of the zygoma, or bony cheek, and ends at the temporal fenestra. It also forms part of the temporal and postorbital bars; Pelanomodon differs from Bulbasaurus in having small bosses on the latter portions of the jugals.[1][10]

Postorbital skull

[edit]

Most of the postorbital bar is made up of the postorbital bones, which are very robust relative to other cryptodontians as in other geikiids. However, compared to other geikiids, the postorbital bar of Bulbasaurus is relatively smooth and free of bosses. The sides of the postorbitals, which would have anchored jaw musculature, are very concave. Near the back, the postorbitals curve and converge to form a somewhat pinched intertemporal bar that overlaps the parietal bones to varying extents. The squamosal bones also contribute to the postorbital bar; its back edge along the postorbital bar is somewhat twisted in Bulbasaurus, which is seen in other cryptodontians but is taken to an extreme by Aulacephalodon and Pelanomodon, where the bone has become entirely twisted such that the interior faces outwards. Projections of the squamosal bones partially surround the posttemporal fenestrae on the rear of the skull, like Aulacephalodon, Pelanomodon, Oudenodon, and Tropidostoma.[1][10]

As for the underlying parietals themselves, they are slightly concave. In front of the parietals are the small midline preparietal bones, which are relatively broad and have a rounded tip, as in Aulacephalodon and Pelanomodon but in contrast to Tropidostoma. The pineal foramen is bordered by the preparietals and parietals, and it is surrounded by a simple ridge instead of being on a raised boss like either the large rhaciocephalids and Endothiodon or some large specimens belonging to Aulacephalodon. On the braincase, no sutures are visible, suggesting that the bones are very fused. The occipital bones are likewise very fused. The contribution of the supraoccipital bones to the back of the skull is unusually extensive and occupies much of the area not part of the squamosals above the level of the foramen magnum. Also unusual are the smaller elements at the back of the skull, namely the postparietals and tabulars. The postparietals are not part of the continuous flat surface at the back of the skull, instead forming a sharp divot; additionally, a strong midline crest is present on the postparietals and do not extend onto other bones. Meanwhile, the tabulars are wider than they are long.[1]

Mandible and postcrania

[edit]

The mandible of Bulbasaurus was largely similar to Aulacephalodon. At the front of the mandible, the two toothless dentary bones fuse at the front to form a continuous beak with a sharp, pointed tip. The somewhat convex front surface of this junction, or the dentary symphysis, is separated from the sides of the dentaries by sharp ridges, a condition also seen in Pelanomodon and Geikia but not seen in Aulacephalodon. Overall, the dentary was tall and robust, the symphysis more so than the rest of the bone. Located at the mid-height of the dentaries are the mandibular fenestrae, which are small and oval, and bordered on top by a dentary shelf that expands into a boss. Asides from the skull, the other portions of Bulbasaurus have not been prepared in depth. The ribs are gently curved and are bicipital in that they have two heads. On the humerus, the deltopectoral crest was robust and strongly separated.[1]

Ontogeny

[edit]

Most skulls referred to Bulbasaurus are 13–16 centimetres (5.1–6.3 in) long, with two skulls (CGP/1/2263 and SAM-PK-K10587) being smaller at 10.9 centimetres (4.3 in) and 10.4 centimetres (4.1 in) respectively. The larger skulls generally belong to mature specimens. While the CGP/1/2263's size is largely due to compression, SAM-PK-K10587 seems to be a genuinely immature individual. Notably, it differs from other specimens in having a shorter and less hooked snout; relatively smaller but still completely erupted tusks; less developed nasal bosses that are more separated by the premaxilla; a narrower interorbital region between the eyes; a wider intertemporal region at the back of the skull; relatively weak depressions in the interorbital and intertemporal regions; no overlap of the parietals by the postorbitals; and minimal twisting of the squamosal on the postorbital bar.[1]

These differences are most likely due to growth, as similar transformations are also seen in Aulacephalodon.[6][10] However, the latter (and all other geikiids where the growth sequence is known) differs from Bulbasaurus in that the degree of overlap of the parietals by the postorbitals does not change; instead, the parietals themselves simply become wider. In this respect, Bulbasaurus retains the ancestral cryptodontian condition, which is also seen in rhachiocephalids as well as Oudenodon, Tropidostoma, and other oudenodontids.[10] Overall, the relatively small Bulbasaurus provides evidence that the growth sequence of large geikiids such as Aulacephalodon did not develop along with their size, but rather was already present ancestrally and was retained as geikiids grew.[1]

Classification

[edit]

In 2017, Bulbasaurus was assigned to the Geikiidae clade of dicynodonts on account of its prominent nasal-frontal ridge, its relatively wide interorbital region, and its twisted squamosal on the postorbital bar. This assignment was supported by a phylogenetic analysis based on that conducted by Kammerer et al. in 2011,[5][11] which found it as the closest relative of Aulacephalodon on the basis of it lacking a ridge behind its tusk (which is ontogenetically influenced). However, this assignment is somewhat questionable, and forcing Bulbasaurus as a basal geikiid outside of the Geikiinae (Aulacephalodon, Geikia, and Pelanomodon) only requires one additional evolutionary step. Overall, the Cryptodontia (including the Geikiidae) were very unstable, suggesting that current datasets may not be able to sufficiently evaluate their relationships. An excerpt from the consensus of two phylogenetic trees, illustrating the relationships between cryptodontians, is shown below.

Tropidostoma, the genus Bulbasaurus was originally assigned to, exhibits two distinct morphologies - a robust morph with short snout and large tusks, and a gracile morph with long snout and small tusks, which probably represents sexual dimorphism as in other dicynodonts.[6][7][10][12][13] However, Bulbasaurus matches neither of those morphologies; it differs from the genus Tropidostoma as a whole in many respects (addressed above). Additionally, even the holotype of Tropidostoma (which is probably immature judging by the unerupted tusks) is larger than adult specimens of Bulbasaurus, which further warrants their separation. The same is true of Bulbasaurus and Aulacephalodon, in addition to their differing boss morphologies and different interorbital widths. Bulbasaurus also differs from the problematic specimens BP/1/763 (assigned once to its own genus, Proaulacocephalodon, or to a juvenile Aulacephalodon[6][10]) and TM 1480 (assigned once to Dicynodon hartzenbergi[5]) by its larger tusks and wider interorbital region, among other characteristics. These specimens are additionally from the younger Cistecephalus assemblage zone.[1]

Paleoecology

[edit]

Although the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone, from where Bulbasaurus hails, is named after the oudenodontid Tropidostoma, Tropidostoma is only the third most common dicynodont in this assemblage zone. Most common is the small Diictodon, over 2000 specimens of which are known from the Tropidostoma AZ alone. Also more common than Tropidostoma is Pristerodon. Other dicynodonts present include Cistecephalus, Dicynodontoides, Emydops, Endothiodon, Oudenodon, Palemydops, and Rhachiocephalus.[14] Notable in the Tropidostoma AZ is the lack of geikiid and dicynodontoid dicynodonts (Dicynodontoides is a diictodont), which is unusual since they must have already diverged from their ancestral lineages by this time; Bulbasaurus happens to fill the former gap.[1]

The Tropidostoma AZ also records the gradual diversification of therocephalians and gorgonopsians.[1] Therocephalians present include Hofmeyria, Ictidosuchoides (most common), Ictidosuchops, Ictidosuchus, and Lycideops; gorgonopsids present include Aelurognathus, Aelurosaurus, Aloposaurus, Cyonosaurus, Gorgonops (most common), Lycaenops, and Scymnognathus.[14] Within the Karoo Supergroup, cynodonts also first appear within the Tropidostoma AZ;[1] they include Abdalodon (formerly assigned to Procynosuchus)[15] and Charassognathus.[16] Rarer members of the Tropidostoma AZ assemblage include the burnetiamorphs Lobalopex[17] and Lophorhinus;[18] parareptiles Pareiasaurus and Saurorictus; the archosauromorph Younginia; and the temnospondyl Rhinesuchus.[14]

Bulbasaurus was probably buried on floodplains surrounding a meandering river up to 350 metres (1,150 ft) wide and with point bars up to 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) in diameter.[1][19] This river flowed from the southern mountains northeast onto an alluvial fan some 500 kilometres (310 mi) wide. The water flow in the rivers was seasonally dependent, but there was probably flowing water year-round. About every 30,000 years, the river banks were breached by flooding, leaving overbank deposits and a series of small, isolated ponds.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Kammerer, C.F.; Smith, R.M.H. (2017). "An early geikiid dicynodont from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone (late Permian) of South Africa". PeerJ. 5 e2913. doi:10.7717/peerj.2913. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5289114. PMID 28168104.

- ^ Smith, R.M.H. (1993). "Vertebrate taphonomy of Late Permian floodplain deposits in the southwestern Karoo Basin of South Africa". PALAIOS. 8 (1): 45–67. Bibcode:1993Palai...8...45S. doi:10.2307/3515221. JSTOR 3515221.

- ^ Kammerer, C.F. [@Synapsida] (2017-01-31). "Not as published, no, but...if one wished to read between the lines concerning certain similarities, I wouldn't stop them" (Tweet). Retrieved 2017-02-11 – via Twitter.

- ^ Sloat, S. (2017). "No, Scientists That Discovered Bulbasaurus Didn't Name It After a Pokémon". Inverse. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- ^ a b c Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Frobisch, J. (2011). "A Comprehensive Taxonomic Revision of Dicynodon (Therapsida, Anomodontia) and Its Implications for Dicynodont Phylogeny, Biogeography, and Biostratigraphy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (sp1): 1–158. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31S...1K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.627074. S2CID 84987497.

- ^ a b c d Tollman, S.M.; Grine, F.E.; Hahn, B.D. (1980). "Ontogeny and sexual dimorphism in Aulacephalodon (Reptilia, Anomodontia)". Annals of the South African Museum. 81: 159–186.

- ^ a b Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Frobisch, J. (2015). "Redescription of Digalodon rubidgei, an emydopoid dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the Late Permian of South Africa". Fossil Record. 18: 43–55. doi:10.5194/fr-18-43-2015.

- ^ Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D. (2009). "A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2018: 1–24.

- ^ Angielczyk, K.D. (2002). "Redescription, phylogenetic position, and stratigraphic significance of the dicynodont genus Odontocyclops (Synapsida: Anomodontia)". Journal of Paleontology. 76 (6): 1047–1059. Bibcode:2002JPal...76.1047A. doi:10.1017/S0022336000057863. S2CID 232344421.

- ^ a b c d e f Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Frobisch, J. (2016). "Redescription of the geikiid Pelanomodon (Therapsida, Dicynodontia), with a reconsideration of "Propelanomodon"". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (1) e1030408. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E0408K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1030408. S2CID 86064011.

- ^ Boos, A.D.S.; Kammerer, C.F.; Schultz, C.L.; Soares, M.B.; Ilha, A.L.R. (2016). "A New Dicynodont (Therapsida: Anomodontia) from the Permian of Southern Brazil and Its Implications for Bidentalian Origins". PLOS ONE. 11 (5) e0155000. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155000B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155000. PMC 4880204. PMID 27224287.

- ^ Sullivan, C.; Reisz, R.R.; Smith, R.M.H. (2003). "The Permian mammal-like herbivore Diictodon, the oldest known example of sexually dimorphic armament". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1511): 173–178. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2189. PMC 1691218. PMID 12590756.

- ^ Ray, S. (2005). "Lystrosaurus (Therapsida, Dicynodontia) from India: taxonomy, relative growth and cranial dimorphism". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1017/S1477201905001574. S2CID 87131692.

- ^ a b c d Smith, R.; Rubidge, B.; van der Walt, Merrill (2012). "Therapsid Biodiversity Patterns and Palaeoenvironments of the Karoo Basin, South Africa". In Chinsamy-Turan, A. (ed.). Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 31–64. ISBN 978-0-253-00533-5.

- ^ Kammerer, C.F. (2016). "A new taxon of cynodont from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone (upper Permian) of South Africa, and the early evolution of Cynodontia". Papers in Palaeontology. 2 (3): 387–397. doi:10.1002/spp2.1046. S2CID 131743432.

- ^ Botha, J.; Abdala, F.; Smith, R. (2009). "The oldest cynodont: new clues on the origin and early diversification of the Cynodontia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 149 (3): 477–492. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00268.x.

- ^ Sidor, C.A.; Hopson, J.A.; Keyser, A.W. (2004). "A new burnetiamorph therapsid from the Teekloof Formation, Permian, of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 938–950. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0938:ANBTFT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85752458.

- ^ Sidor, C.A.; Smith, R.M.H. (2007). "A second burnetiamorph therapsid from the Permian Teekloof Formation of South Africa and its associated fauna". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 420–430. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[420:ASBTFT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86173425.

- ^ Smith, R.M.H. (1987). "Morphology and Depositional History of Exhumed Permian Point Bars in the Southwestern Karoo, South Africa". Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. 57 (1): 19–29.