Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bullwhip effect

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2013) |

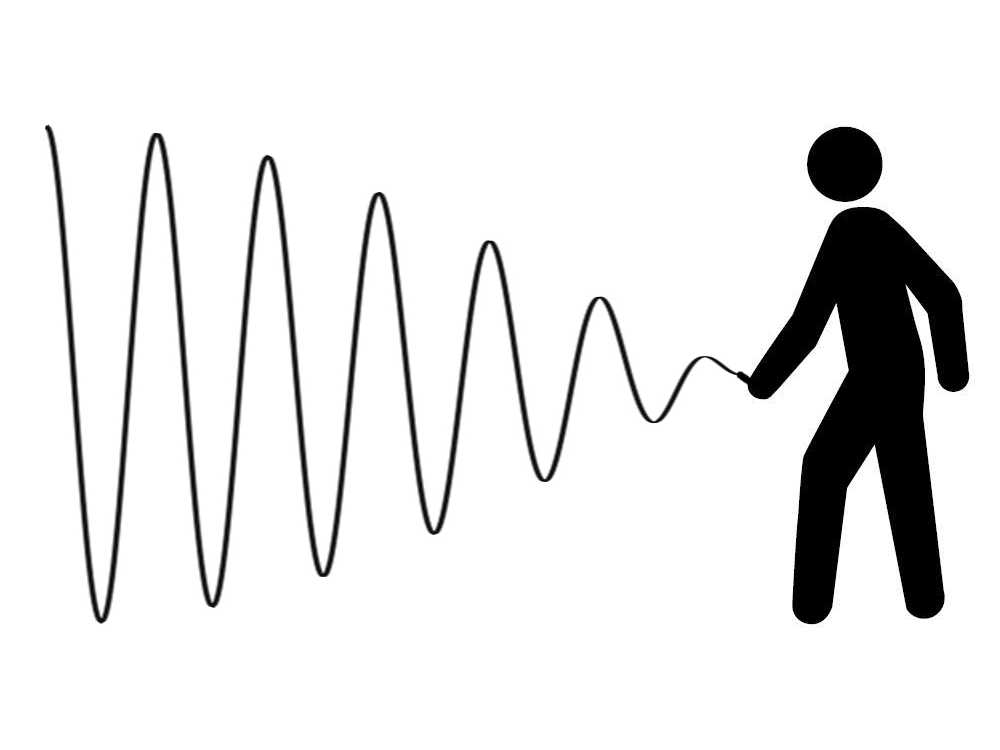

The bullwhip effect is a supply chain phenomenon where orders to suppliers tend to have a larger variability than sales to buyers, which results in an amplified demand variability upstream. In part, this results in increasing swings in inventory in response to shifts in consumer demand as one moves further up the supply chain. The concept first appeared in Jay Forrester's Industrial Dynamics (1961)[1] and thus it is also known as the Forrester effect. It has been described as "the observed propensity for material orders to be more variable than demand signals and for this variability to increase the further upstream a company is in a supply chain".[2]

Research at Stanford University helped incorporate the concept into supply chain vernacular using a story about Volvo. Suffering a glut in green cars, sales and marketing developed a program to sell the excess inventory. While successful in generating the desired market pull, manufacturing did not know about the promotional plans. Instead, they read the increase in sales as an indication of growing demand for green cars and ramped up production.[3]

Research indicates a fluctuation in point-of-sale demand of five percent will be interpreted by supply chain participants as a change in demand of up to forty percent. Much like cracking a whip, a small flick of the wrist - a shift in point of sale demand - can cause a large motion at the end of the whip - manufacturers' responses.[4]

Causes

[edit]

Because customer demand is rarely perfectly stable, businesses must forecast demand to properly position inventory and other resources. Forecasts are based on statistics, and they are rarely perfectly accurate. Because forecast errors are expected, companies often carry an inventory buffer called "safety stock".

Moving up the supply chain from end-consumer to raw materials supplier, each supply chain participant has greater observed variation in demand and thus greater need for safety stock. In periods of rising demand, down-stream participants increase orders. In periods of falling demand, orders fall or stop, thereby not reducing inventory. The effect is that variations are amplified as one moves upstream in the supply chain (further from the customer). This sequence of events is well simulated by the beer distribution game that was developed by MIT Sloan School of Management in the 1960s.

- Disorganisation

- Lack of communication

- Free return policies

- Order batching

- Price variations

- Demand information

- Simply human greed and exaggeration

The causes can further be divided into behavioral and operational causes.

Behavioral causes

[edit]The first theories focusing onto the bullwhip effect were mainly focusing on the irrational behavior of the human in the supply chain, highlighting them as the main cause of the bullwhip effect. Since the 90's, the studies evolved, placing the supply chain's misfunctioning at the heart of their studies abandoning the human factors.[5]

Previous control-theoretic models have identified as causes the tradeoff between stationary and dynamic performance[6] as well as the use of independent controllers.[7] In accordance with Dellaert et al. (2017),[8] one of the main behavioral causes that contribute to the bullwhip effect is the under-estimation of the pipeline.[9] In addition, the complementary bias, over-estimation of the pipeline, also has a negative effect under such conditions. Nevertheless, it has been shown that when the demand stream is stationary, the system is relatively robust to this bias. In such situations, it has been found that biased policies (both under-estimating and over-estimating the pipeline) perform just as well as unbiased policies.

Some others behavioral causes can be highlighted:

- Misuse of base-stock policies

- Mis-perceptions of feedback and time delays. In 1979, Buffa and Miller highlighted that in their example. If a retailer sees a permanent drop of 10% of the demand on day 1, he will not place a new order until day 10. That way, the wholesaler is going to notice the 10% drop at day 10 and will place his order on day 20. The longer the supply chain is, the bigger this delay will be and the player at the end of the supply chain will discover the decline of the demand after several weeks.

- Panic ordering reactions after unmet demand

- Perceived risk of other players' bounded rationality. Following the logic of the example of Buffa and Miller, after several weeks of producing at the classical rate, the producer will receive the information of the demand drop. As the drop was 10%, during the delay of the information's circulation the producer had a surplus of 11% per day, accumulated since day 1. He is thus more inclined to cut more than the necessary production.[2]

Human factors influencing the behavior in supply chains are largely unexplored. However, studies suggest that people with increased need for safety and security seem to perform worse than risk-takers in a simulated supply chain environment. People with high self-efficacy experience less trouble handling the bullwhip-effect in the supply chain.[10]

Operational causes

[edit]A seminal Lee et al. (1997) study found that the bullwhip effect did not solely result from irrational decision making: it found that under some circumstances it is rational for a firm to order with greater variability than variability of demand, i.e., distort demand and cause the bullwhip effect. They established a list of four major factors which cause the bullwhip effect: demand signal processing, rationing game, order batching, and price variations.[2] This list has become a standard and is used as a framework to identify bullwhip effect.[citation needed]

- Demand forecast updating is applied individually by all members of a supply chain. In order to guard against unexpected events, a member of the chain who is ordering will add safety stock to the amount actually needed. When the supplier of that member places an order to its own supplier, it will also add safety stock. The more members of the chain, the more safety stock will be made, resulting in an artificial increase in demand.[11]

- Order batching is the preference of most companies to accumulate demand before ordering, with the intent of reducing cost and simplifying logistics. This approach allows them to benefit from more revenue per order without a comparable increase in transportation cost via economy of scale. That can manifest by allowing them to order a full truck or container load, where partial loads are less efficient in terms of transportation cost per unit. Consolidation of orders in this way creates an artificial variability in demand, which potentially increases the bullwhip effect.

- Price fluctuations can be a result of inflationary factors, quantity discounts, or sales. This instability tends to stimulate customers to buy larger quantities than they require. In cases where sales economy is higher than stocking expense, they may buy more than is immediately needed in order to gain bulk discounts. This increases the variability by having large spikes of demand followed by longer periods without orders while the excess stock is sold off, which makes it more difficult for suppliers to predict demand. The resulting uncertainty can contribute to the bullwhip effect. While suppliers can counter this by removing or reducing discounts, this risks loss of business to competitors who continue to offer more or larger incentives.

- Rationing and gaming is when a retailer limits order quantities by providing only a percentage of the order, but the buyer acts on this knowledge by placing larger orders in hopes of getting closer to the actual desired quantity. Rationing and gaming generate inconsistencies in the ordering information that is being received, and may feed into the bullwhip effect.[12]

Other operational causes include:

- Dependent demand processing

- Forecast errors

- Adjustment of inventory control parameters with each demand observation

- Lead time variability (forecast error during replenishment lead time)

- Lot-sizing/order synchronization

- Consolidation of demands

- Transaction motive

- Quantity discounts

- Trade promotion and forward buying

- Anticipation of shortages

- Allocation rule of suppliers

- Shortage gaming

- Lean and JIT style management of inventories and a chase production strategy

Consequences

[edit]In addition to greater safety stocks, the described effect can lead to either inefficient production or excessive inventory, as each producer needs to fulfill the demand of its customers in the supply chain. This also leads to a low utilization of the distribution channel.

In spite of having safety stocks there is still the hazard of stock-outs which result in poor customer service and lost sales. In addition to the (financially) hard measurable consequences of poor customer services and the damage to public image and loyalty, an organization has to cope with the ramifications of failed fulfillment which may include contractual penalties. Moreover, repeated hiring and dismissal of employees to manage the demand variability induces further costs due to training and possible lay-offs.

The impact of the bullwhip effect has been especially acute at the beginning stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, when sudden spikes in demand for everything from medical supplies such as masks or ventilators[13] to consumer items such as toilet paper or eggs created feedback loops of panic buying, hoarding, and rationing.[14]

Countermeasures

[edit]Information sharing across the supply chain is an effective strategy to mitigate the bullwhip effect. For example, it has been successfully implemented in Wal-Mart's distribution system. Individual Wal-Mart stores transmit point-of-sale (POS) data from the cash register back to corporate headquarters several times a day. This demand information is used to queue shipments from the Wal-Mart distribution center to the store and from the supplier to the Wal-Mart distribution center. The result is near-perfect visibility of customer demand and inventory movement throughout the supply chain. Better information leads to better inventory positioning and lower costs throughout the supply chain.

Another recommended strategy to limit the bullwhip effect is order smoothing.[7] Previous research has demonstrated that order smoothing and the bullwhip effect are concurrent in industry.[15] It has been proved that order smoothing is beneficial for the system's performance when the demand is stationary. However, its impact is limited to the worst-case order amplification when the demand is unpredictable. Having said that, dynamic analysis reveals that order smoothing can degrade performance in the presence of demand shocks. The opposite bias (i.e., over-reaction to mismatches), on the other hand, degrades the stationary performance but can increase dynamic performance; controlled over-reaction can aid the system reach its new goals quickly. The system, nevertheless, is considerably sensitive to that behaviour; extreme over-reaction significantly reduces performance. Overall, unbiased policies offer in general good results under a large range of demand types. Although these policies do not result in the best performance under certain criteria. It is always possible to find a biased policy that outperforms an unbiased policy for any one performance metric.

Methods intended to reduce uncertainty, variability, and lead time:

- Vendor-managed inventory (VMI)

- Just in time replenishment (JIT)

- Demand-driven MRP

- Strategic partnership

- Information sharing

- Smooth the flow of products

- Coordinate with retailers to spread deliveries evenly

- Reduce minimum batch sizes

- Smaller and more frequent replenishments

- Eliminate pathological incentives

- Every day low price policy

- Restrict returns and order cancellations

- Order allocation based on past sales instead of current size in case of shortage

Financial bullwhip

[edit]Many studies demonstrate the bullwhip effect in a supply chain from different perspectives, including information sharing (Lee et al., 2000),[16] information distortion (Lee et al., 2004),[17] bankruptcy events (Lee et al., 2004, Mizgier et al., 2012[18]) and systematic risk (Osadchiy et al., 2015).[19] Most of them devote themselves to exploring the bullwhip effect from the perspectives of inventory flow risk and information flow risk rather than that of cash flow risk. For a firm's internal liquidity risk (Chen et al., 2011),[20] it is an appropriate proxy for a firm's financial risk.

Evolving from the notion of a stock derived bullwhip effect, there exists a similar, "financial bullwhip effect", explored in (Chen et al., 2013),[21] on bondholders' wealth along a supply chain by examining whether the internal liquidity risk effect on bond yield spreads becomes greater upwardly along the supply chain counterparties.

Financial ripple effect

[edit]This is more generally modelled in (Proselkov et al., 2023),[22] which uses complex adaptive systems modelling to study cascade failures as a consequence of financial bullwhips. Specifically, they create an agent-based supply network simulation model capturing the behaviours of companies with asymmetric power dynamics with their partners. To remain operational, they maximise their liquidity by negotiating longer repayment terms and cheaper financing, thus distributing risk onto weaker companies and propagating financial stress. This results in network-wide breakdown.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Forrester, Jay Wright (1961). Industrial Dynamics. MIT Press.

- ^ a b c Lee, H.; Padmanabhan, V.; Whang, S. (1997). "Information distortion in a supply chain: The bullwhip effect". Management Science. 43 (4): 546–558. doi:10.1287/mnsc.43.4.546.

- ^ Chain reaction: Managing a supply chain is becoming a bit like rocket science, The Economist, 31 January 2002

- ^ "Bullwhip effect. The bullwhip effect is a distribution channel phenomenon in which forecasts yield supply chain inefficiencies. It refers to increasing swings i". ww.en.freejournal.org. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ "Faculty of Science" (PDF).

- ^ Hoberg, K.; Thonemann, U. (2014). "Modeling and analyzing information delays in supply chains using transfer functions". International Journal of Production Economics. 156: 132–145. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.05.019.

- ^ a b Disney, S. (2008). "Supply chain aperiodicity, bullwhip and stability analysis with Jury's inners". IMA Journal of Management Mathematics. 19 (2): 101–116. doi:10.1093/imaman/dpm033.

- ^ Udenio, Maximiliano; Vatamidou, Eleni; Fransoo, Jan C.; Dellaert, Nico (2017-10-03). "Behavioral causes of the bullwhip effect: An analysis using linear control theory". IISE Transactions. 49 (10): 980–1000. doi:10.1080/24725854.2017.1325026. ISSN 2472-5854. S2CID 53692411.

- ^ Sterman, J. (1989). "Modeling managerial behavior: Misperceptions of feedback in a dynamic decision making experiment". Management Science. 35 (3): 321–339. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.3.321. hdl:1721.1/2184.

- ^ Brauner P., Runge S., Groten M., Schuh M., Ziefle M. (2013). Human Factors in Supply Chain Management. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 8018, 2013, pp 423-432

- ^ "Faculty of Science" (PDF).

- ^ "Opentextbooks". 24 February 2015.

- ^ "How health systems are responding as COVID-19 squeezes the medical supply chain". Supply Chain Dive. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ "What procurement managers should expect from a 'bullwhip on crack'". Supply Chain Dive. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ Bray, R.L.; Mendelson, H. (2015). "Production smoothing and the bullwhip effect". Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 17 (2): 208–220. doi:10.1287/msom.2014.0513.

- ^ Hau L. Lee; Kut C. So; Christopher S. Tang (2000). "The Value of Information Sharing in a Two-Level Supply Chain". Management Science. 46 (5): 626–643. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.5.626.12047.

- ^ Hau L. Lee; V. Padmanabhan; Seungjin Whang (2004). "Information Distortion in a Supply Chain: The Bullwhip Effect". Management Science. 50 (12): 1875–1886. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1040.0266.

- ^ Mizgier, Kamil J.; Wagner, Stephan M.; Holyst, Janusz A. (2012). "Modeling defaults of companies in multi-stage supply chain networks". International Journal of Production Economics. 135 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.09.022.

- ^ Nikolay Osadchiy; Vishal Gaur; Sridhar Seshadri (2015). "Systematic Risk in Supply Chain Networks". Management Science. 62 (6): 1755–1777. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2015.2187.

- ^ Chen, Minjia; Guariglia, Alessandra (2013). "Internal financial constraints and firm productivity in China: Do liquidity and export behavior make a difference?". Journal of Comparative Economics. 41 (4): 1123–1140. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2013.05.003.

- ^ Chen, Tsung Kang; Liao, Hsien Hsing; Kuo, Hui Ju (2013). "Internal liquidity risk, financial bullwhip effects, and corporate bond yield spreads: Supply chain perspectives". Journal of Banking and Finance. 37 (7): 2434–2456. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.02.011.

- ^ Yaniv Proselkov; Jie Zhang; Liming Xu; Erik Hofmann; Thomas Y. Choi; Dale Rogers; Alexandra Brintrup (2023). "Financial ripple effect in complex adaptive supply networks: an agent-based model". International Journal of Production Research. 62 (3): 823–845. doi:10.1080/00207543.2023.2173509. S2CID 257149106.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lee, Hau L; Padmanabhan, V.; Whang, Seungjin (1997). "The Bullwhip Effect in Supply Chains". Sloan Management Review. 38 (3): 93–102.

- Mason-Jones, Rachel; Towill, Dennis R. (2000). "Coping with Uncertainty: Reducing "Bullwhip" Behaviour in Global Supply Chains". Supply Chain Forum. 1: 40–44. doi:10.1080/16258312.2000.11517070. S2CID 7920876.

- Bean, Michael (2006). "Bullwhips and Beer: Why Supply Chain Management is so Difficult". /forio (blog).[unreliable source?]

Literature

[edit]- Bray, Robert L., and Haim Mendelson. "Information transmission and the bullwhip effect: An empirical investigation." Management Science 58.5 (2012): 860–875.

- Buffa Elwood S and Jeffrey G Miller. 1979. Production-Inventory Systems : Planning and Control. 3d ed. Homewood Ill: Richard D. Irwin.

- Cannella S., and Ciancimino E. (2010). On the bullwhip avoidance phase: supply chain collaboration and order smoothing. International Journal of Production Research, 48 (22), 6739-6776

- Chen, Y. F., Z. Drezner, J. K. Ryan and D. Simchi-Levi (2000), Quantifying the Bullwhip Effect in a Simple Supply Chain: The Impact of Forecasting, Lead Times and Information. Management Science, 46, 436–443.

- Chen, Y. F., J. K. Ryan and D. Simchi-Levi (2000), The Impact of Exponential Smoothing Forecasts on the Bullwhip Effect. Naval Research Logistics, 47, 269–286.

- Chen, Y. F., Z. Drezner, J. K. Ryan and D. Simchi-Levi (1998), The Bullwhip Effect: Managerial Insights on the Impact of Forecasting and Information on Variability in a Supply Chain. Quantitative Models for

- Disney, S.M., and Towill, D.R. (2003). On the bullwhip and inventory variance produced by an ordering policy. Omega, the International Journal of Management Science, 31 (3), 157–167.

- Lee, H.L., Padmanabhan, V., and Whang, S. (1997). Information distortion in a supply chain: the bullwhip effect. Management Science, 43 (4), 546–558.

- Lee, H.L. (2010). Taming the bullwhip. Journal of Supply Chain Management 46 (1), pp. 7–7.

- Supply Chain Management, S. Tayur, R. Ganeshan and M. Magazine, eds., Kluwer, pp. 417–439.

- Selwyn, B. (2008) Bringing Social Relations Back In: (re)Conceptualising the 'Bullwhip Effect' in global commodity chains. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy, 3 (2)156-175.

- Tempelmeier, H. (2006). Inventory Management in Supply Networks—Problems, Models, Solutions, Norderstedt:Books on Demand. ISBN 3-8334-5373-7.

External links

[edit]- What the "beer game" can teach about supply chain challenges segment from the Jun 29, 2021 episode of Marketplace with Professor Willy Shih of the Harvard Business School interviewed by Kai Ryssdal