Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Volvo

View on Wikipedia

The Volvo Group (Swedish: Volvokoncernen; legally Aktiebolaget Volvo, shortened to AB Volvo, stylized as VOLVO) is a Swedish multinational manufacturing corporation headquartered in Gothenburg. While its core activity is the production, distribution and sale of trucks, buses and construction equipment, Volvo also supplies marine and industrial drive systems and financial services. In 2016, it was the world's second-largest manufacturer of heavy-duty trucks with its subsidiary Volvo Trucks.[5]

Key Information

Volvo was founded in 1927. Initially involved in the automobile industry, Volvo expanded into other manufacturing sectors throughout the twentieth century. Automobile manufacturer Volvo Cars, also based in Gothenburg, was part of AB Volvo until 1999, when it was sold to the Ford Motor Company. Since 2010 Volvo Cars has been owned by the automotive company Geely Holding Group. Both AB Volvo and Volvo Cars share the Volvo logo and cooperate in running the World of Volvo museum in Gothenburg, Sweden.[6]

The corporation was first listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange in 1935, and was listed on the American NASDAQ from 1985 to 2007.[7] Volvo is one of Sweden's largest companies by market capitalisation and revenue.[8]

History

[edit]Early years and international expansion

[edit]

The brand name Volvo was originally registered as a trademark in May 1911, with the intention to be used for a new series of SKF ball bearings. It means "I roll" in Latin, conjugated from "volvere". The idea was short-lived, and SKF decided to simply use its initials as the trademark for all its bearing products.[9]

In 1924, Assar Gabrielsson, an SKF sales manager, and Gustav Larson, a KTH educated engineer, decided to start construction of a Swedish car. They intended to build cars that could withstand the rigours of the country's rough roads and cold temperatures.[10]

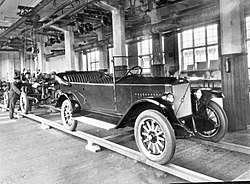

AB Volvo began activities on 10 August 1926. After one year of preparations involving the production of ten prototypes, the firm was ready to commence the car-manufacturing business within the SKF group. The Volvo Group itself considers it started in 1927, when the first car, a Volvo ÖV 4, rolled off the production line at the factory in Hisingen, Gothenburg.[11] Only 280 cars were built that year.[12] The first truck, the "Series 1", debuted in January 1928, as an immediate success and attracted attention outside the country.[9] In 1930, Volvo sold 639 cars,[12] and the export of trucks to Europe started soon after; the cars did not become well known outside Sweden until after World War II.[12] AB Volvo was introduced at the Stockholm Stock Exchange in 1935 and SKF then decided to sell its shares in the company. By 1942, Volvo acquired the Swedish precision engineering company Svenska Flygmotor (later renamed as Volvo Aero).[9]

Pentaverken, which had manufactured engines for Volvo, was acquired in 1935, providing a secure supply of engines and entry into the marine engine market.[13]

The first bus, named B1, was launched in 1934, and aircraft engines were added to the growing range of products at the beginning of the 1940s. Volvo was also responsible for producing the Stridsvagn m/42. In 1963, Volvo opened the Volvo Halifax Assembly plant, the first assembly plant in the company's history outside of Sweden in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

In 1950, Volvo acquired the Swedish construction and agricultural equipment manufacturer Bolinder-Munktell.[14] Bolinder-Munktell was renamed as Volvo BM in 1973.[15] In 1979, Volvo BM's agricultural equipment business was sold to Valmet.[16] Later, through restructuring and acquisitions, the remaining construction equipment business became Volvo Construction Equipment.[14]

In the 1970s, Volvo started to move away from car manufacturing to concentrate more on heavy commercial vehicles. The car division focused on models aimed at upper middle-class customers to improve its profitability.[17]

Partnerships and merging attempts

[edit]In 1977, Volvo tried to combine operations with rival Swedish automotive group Saab-Scania, but the latter company rejected it.[9]

Between 1978[9] and 1981, Volvo acquired Beijerinvest, a trading company involved in the oil, food, and finance businesses. In 1981, those sectors represented about three-quarters of Volvo's revenue, while the automotive sector amounted for most of the rest. In 1982, the company completed the acquisition of White Motor Corporation's assets.[17]

In the early 1970s, French manufacturer Renault and Volvo started to collaborate.[18] In 1978, Volvo Car Corporation was spun off as a separate company within the Volvo group[19] and Renault acquired a minority stake,[9] before selling it back in the 1980s after a restructuring.[18] In the 1990s, Renault and Volvo deepened their collaboration and both companies partnered in purchasing, research and development and quality control while increasing their cross-ownership. Renault would assist Volvo with entry-level and medium segment vehicles and in return, Volvo would share technology with Renault in upper segments. In 1993, a 1994 Volvo-Renault merger deal was announced. The deal was barely accepted in France, but it was opposed in Sweden, and the Volvo shareholders and company board voted against it.[9][18] The alliance was officially dissolved in February 1994 and Volvo sold off its minority Renault stake in 1997.[9] In the 1990s, Volvo also divested from most of its activities outside vehicles and engines.[9]

In 1991, the Volvo Group participated in a joint venture with Japanese automaker Mitsubishi Motors at the former DAF plant in Born, Netherlands. The operation, branded NedCar, began producing the first generation Mitsubishi Carisma alongside the Volvo S40/V40 in 1996.[20][21] During the 1990s, Volvo also partnered with the American manufacturer General Motors. In 1999, the European Union blocked a merger with Scania AB.[9] Israel's Merkavim is partly owned by Volvo.[22]

Refocusing on heavy vehicles

[edit]

In January 1999, Volvo Group sold Volvo Car Corporation to Ford Motor Company for $6.45 billion. The division was placed within Ford's Premier Automotive Group alongside Jaguar, Land Rover and Aston Martin. Volvo engineering resources and components would be used in various Ford, Land Rover and Aston Martin products, with the second generation Land Rover Freelander designed on the same platform as the second generation Volvo S80. The Volvo T5 petrol engine was used in the Ford Focus ST and RS performance models, and Volvo's satellite navigation system was used on certain Aston Martin Vanquish, DB9 and V8 Vantage models.[23][24][25] In November 1999, Volvo Group purchased a 5% stake in Mitsubishi Motors, as part of a partnership deal for the truck and bus business.[26] In 2001, after DaimlerChrysler bought a large Mitsubishi Motors stake,[27] Volvo sold its shares to the former.[28]

Renault Véhicules Industriels (which included Mack Trucks, but not Renault's stake in Irisbus) was sold to Volvo during January 2001, and Volvo renamed it Renault Trucks in 2002. Renault became AB Volvo's biggest shareholder, with a 19.9% stake (in shares and voting rights) as part of the deal.[29] Renault increased its shareholding to 21.7% by 2010.[30]

AB Volvo acquired 13% of the shares in the Japanese truck manufacturer Nissan Diesel (later renamed UD Trucks) from Nissan (part of the Renault-Nissan Alliance) during 2006, becoming a major shareholder. Volvo Group took complete ownership of Nissan Diesel in 2007 to extend its presence in the Asian Pacific market.[10][31]

Renault sold 14.9% of their stake in AB Volvo in October 2010 (comprising 14.9% of the share capital and 3.8% of the voting rights) for €3.02 billion. This share sale left Renault with around 17.5% of Volvo's voting rights.[30] Renault sold their remaining shares in December 2012 (comprising 6.5% of the share capital and 17.2% of the voting rights at the time of transaction) for €1.6 billion, leaving Swedish industrial investment group Aktiebolaget Industrivärden [sv] as the largest shareholder, with 6.2% of the share capital and 18.7% of the voting rights.[32][33] That same year, Volvo sold Volvo Aero to the British company GKN.[34] In 2017 Volvo Cars owner Geely became the largest Volvo shareholder by number of shares after acquiring an 8.2% stake, displacing Industrivärden. Industrivärden kept more voting rights than Geely (Geely getting a 15.8%).[35]

In December 2013, Volvo sold its Volvo Construction Equipment Rents division to Platinum Equity.[36] In November 2016, Volvo announced its intention of divesting its Government Sales division, made up mainly of Renault Trucks' Renault Trucks Defense but also of Panhard, ACMAT, Mack Defense in the United States, and Volvo Defense.[37] The project for selling the division was later abandoned and, in May 2018, Volvo reorganized Renault Trucks Defense and renamed it Arquus.[38]

In December 2018, Volvo announced it intended to sell a 75.1% controlling stake of its car telematics subsidiary WirelessCar to Volkswagen with the aim of focusing on telematics for commercial vehicles.[39] The sale was completed in March 2019.[40]

In December 2019, Volvo and Isuzu announced their intention of forming a strategic alliance on commercial vehicles. As part of the agreement, Volvo would sell UD Trucks to Isuzu.[41] The "final agreements" for the alliance were signed in October 2020, with UD Trucks sale pending on regulatory clearances.[42] The sale was completed in April 2021.[43]

In the early 2020s, Volvo partnered with other manufacturers to deploy infrastructure for non-hydrocarbon energies. In April 2020, Volvo and Daimler (later Daimler Truck) announced that the former planned to acquire half of Daimler's fuel cell business, forming a joint venture between the two companies.[44] In March 2021, the fuel cell business was reorganised as a joint venture called Cellcentric.[45] In December 2021, Volvo, Daimler Truck, and Traton agreed to the formation of an equally owned joint venture aimed to build an electric vehicle charging network for heavy vehicles in Europe.[46] In December 2022, the joint venture (called Commercial Vehicle Charging Europe) began operations under the trade name Milence.[47]

In April 2021, Volvo announced that it had signed up a new partnership with steel manufacturer SSAB to develop fossil fuel-free steel for future use in Volvo's vehicles.[48] The partnership is derived from SSAB's own green steel venture, HYBRIT.[49]

In November 2023, Volvo acquired Proterra's battery business for US$210 million.[50]

Volvo has announced that it is developing trucks with combustion engines that run on hydrogen. Commercial tests will begin in early 2026.[51]

Corporate

[edit]Business

[edit]

Volvo Group's operations include:

- Volvo Trucks (midsize-duty trucks for regional transportation and heavy-duty trucks for long-distance transportation, as well as heavy-duty trucks for the construction work segment)

- Mack Trucks (light-duty trucks for close distribution and heavy-duty trucks for long-distance transportation)

- Renault Trucks (heavy-duty trucks for regional transportations and heavy-duty trucks for the construction work segment)

- Arquus (military vehicles)[52]

- Dongfeng Commercial Vehicles (45%) (trucks)

- VE Commercial Vehicles Limited Ltd., India (VECV), a joint venture between Volvo Group and Eicher Motors Limited in which Volvo holds 45.6% (trucks and buses)

- Volvo Construction Equipment (construction equipment)

- SDLG (70%) (construction equipment)

- Volvo Group Venture Capital (corporate investment company)

- Volvo Buses (complete buses and bus chassis for city traffic, line traffic and tourist traffic)

- Volvo Financial Services (customer financing, inter-group banking, as real estate administration)

- Volvo Penta (marine engine systems for leisure boats and commercial shipping, diesel engines and drive systems for industrial applications)

- Volvo Energy (management and support for electric vehicles, batteries and electrification networks)[53]

According to the company, in 2021 almost two-thirds (62%) of its revenue came from trucks and services related to them. Second came construction equipment (25%), and the rest was from buses, marine engines, and minor operations, each of them below 5%.[54]

Production facilities

[edit]

Volvo has various production facilities. As of 2022[update], it has plants in 19 countries, with 10 other countries having independent assemblers of Volvo products. The company also has product development, distribution, and logistics centers.[55] Its first plant for vehicle assembly, on the Hisingen island, was owned by SKF until it was made part of the Volvo company in 1930.[9] That year, Volvo acquired its supplier of engines in Skövde (Pentavarken).[56] In 1942, Volvo acquired its supplier of transmissions, Köpings Mekaniska Verkstad,[57] located in the town of Köping. In 1954, Volvo built a new truck assembly plant in Gothenburg and, in 1959–[9] 1964,[58] a car assembly plant in Torslanda.[9] The first truly branched away plant of Volvo was the Floby gearbox plant (100 kilometers to the northeast of Gothenburg), incorporated in 1958. In the 1960s and early 1970s, Volvo and its assembly partners opened plants in Canada, Belgium, Malaysia,[56] and Australia.[59] In the early part of that period Volvo also started to venture into vehicles other than passenger cars and road-going commercial vehicles by acquiring the Eskilstuna plant (Bolinder-Munktell).[56] From the 1970s onwards, Volvo set up various facilities (Bengtsfors, Lindesberg, Vara, Tanumshede, Färgelanda,[56] Borås[60]), most of them within a 150-kilometer radius of Gothenburg,[56] and gradually acquired the Dutch DAF car plants.[9] It also established its first South American plant in Curitiba, Brazil.[61]

From the mid-1970s onwards, Volvo began building assembly plants with smaller assembly lines, more worker-centric and with better use of automation, leaving Fordism. These were Kalmar (car assembly, built in 1974),[58] Tuve (truck assembly, 1982)[58][62] and Uddevalla (car assembly, 1989). Kalmar and Uddevalla were closed down in the early 1990s, following yearly losses.[58] The Tuve plant (called the LB plant) replaced the Gothenburg plant (X plant) for truck assembly through the 1980s, as the former could produce more technologically complex models.[62] In 1982, Volvo gained its first plant in the United States, the New River Valley plant in Dublin, Virginia, after acquiring the assets of the White Motor Corporation.[17] Starting in the late 1980s, Volvo expanded its limited bus production capabilities through acquisitions in various countries (Swedish Saffle Karroseri, Danish Aabenraa, German Drögmöller Karroserien, Canadian Prévost Car, Finnish Carrus, American Nova Bus, Mexican Mexicana de Autobuses). In the late 1990s, after a short-lived joint venture with Polish manufacturer Jelcz, Volvo built its main bus production hub for Europe in Wrocław.[61] In the 1990s, Volvo also increased its construction equipment assets by acquiring the Swedish company Åkerman and the construction equipment division of Samsung Heavy Industries.[63] In 1998, the company opened an assembly facility for its three main heavy product lines (trucks, construction equipment, and buses) near Bengaluru, India.[61]

Volvo sold all its car manufacturing assets in 1999.[61]

Following the acquisition of Renault Véhicules Industriels[61] and Nissan Diesel[64] in the 2000s, Volvo gained various production facilities in Europe, North America, and Asia.[61][64]

In 2014, Volvo's Volvo Construction Equipment acquired the haul truck manufacturing division of Terex Corporation, which included five truck models and a manufacturing facility in Motherwell, Scotland.[65][66][67]

| Volvo production sites as of October 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Company | Plants |

| Volvo Trucks |

|

| Renault Trucks |

|

| Mack Trucks |

|

| Volvo Construction Equipment |

|

| Volvo Buses |

|

| VE Commercial Vehicles |

|

| Dongfeng Truck |

|

| SDLG |

|

| Volvo Penta | |

| Notes | |

Minority owned by Volvo.

| |

| Sources | |

| [55][59][60][61][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88] | |

Trademark

[edit]Volvo Trademark Holding AB is equally owned by AB Volvo and Volvo Car Corporation.[89]

The main activity of the company is to own, maintain, protect and preserve the Volvo trademarks, including Volvo, the Volvo branding symbols (grille slash and iron mark), Volvo Penta, on behalf of its owners and to license these rights to its owners. The day-to-day work is focused upon maintaining the global portfolio of trademark registrations, and to extend sufficiently the scope of the registered protection for the Volvo trademarks.

The main business is also to act against unauthorised registration and use (including counterfeiting) of trademarks identical or similar to the Volvo trademarks on a global basis.[90]

Collaboration with universities and colleges

[edit]Volvo has a strategic collaboration within research and recruitment with a number of selected colleges and universities, such as Penn State University, INSA Lyon, EMLYON Business School, NC State University, Sophia University, Chalmers University of Technology, The Gothenburg School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg, Mälardalen University College, and the University of Skövde.[91]

Communication campaigns

[edit]In November 2013, Volvo Trucks enlisted Jean-Claude Van Damme to perform a split between two moving trucks in reverse. The goal of this campaign, titled "Epic Split," was to demonstrate the stability and precision of their "Dynamic Steering" model.[92] In just three weeks, the video went viral, garnering over 61 million views on YouTube.[93]

Two years after the "Epic Split", Volvo Trucks aimed to demonstrate the durability of one of their trucks by handing over the controls to a four-year-old girl named Sophie. Conceptualized by the Swedish agency Forsman and Bodenfors, the widely shared video clip features Sophie using a remote control to navigate the truck through various obstacles, showcasing the vehicle's robustness and precision.[94]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It includes financial information attributable to both AB Volvo proper and its consolidated and non-consolidated affiliates (such as subsidiaries and joint ventures), collectively known as the Volvo Group.

References

[edit]- ^ "Annual Report 2024" (PDF). AB Volvo. pp. 6, 35, 38–39, 59. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ^ "The foundations of Volvo Group". Volvo Group. 14 April 1927. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "La historia de Volvo". Auto Bild España (in Spanish). 17 November 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "La historia de Volvo". Todas las noticias de coches (in Spanish). 23 February 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "Annual and Sustainability Report 2016" (PDF). Volvo. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Home". Volvo Museum. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Volvo to quit Nasdaq". Toronto Star. 14 June 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ "Largest Swedish companies by market capitalization". companiesmarketcap.com. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pederson, Jay P. (June 2005). "AB Volvo". International Directory of Company Histories. Vol. 67. St. James Press. pp. 378–383. ISBN 978-1-5586-2512-9.

- ^ a b "History time-line : Volvo Group – Global". Volvo. Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ Volvo Group Global. "Volvo 80 years". Volvo. Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Georgano, G. N. Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886–1930. (London: Grange-Universal, 1985) ISBN 9781590844915

- ^ "1930 – History: Volvo Penta". Volvo Penta. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b Eliasson, G (2013). "Automotive dinamics in regional economies". In Pyka, Andreas; Burghof, Hans-Peter (eds.). Innovation and Finance. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-135-08491-2. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Heccből támasztották fel a Volvo híres traktormárkáját" (in Hungarian). Agrarszektor.hu. 6 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "Zo zou de Volvo BM er nu uit kunnen zien" (in Dutch). Mechaman.nl. 24 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Vinocur, John (17 May 1982). "Volvo diversifying away from autos". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Donnelly, Tom; Donnelly, Tim; Morris, David (2004). "Renault 1985–2000: From bankruptcy to profit" (PDF). Working papers (Caen Innovation Marché Entreprise) (30). OCLC 799704146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Styhre, Alexander (2007). The Innovative Bureaucracy: Bureaucracy in an Age of Fluidity. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96433-0. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Mitsubishi Motors Corporation Vehicle Manufacturer Strategic Insight Archived 23 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Automotive World (subscription required)

- ^ "Once upon a time..." History, Nedcar.nl website". Nedcar.nl. 1 May 2006. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ "Volvo criticized for West Bank armoured buses". The Local. 1 February 2017.

- ^ Simister, John (November 2006). "Volvo C30 T5 SE". Evo. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

The T5 petrol engine is almost the same as the one borrowed from Volvo by Ford for the Focus ST...

- ^ "ASTON'S CLEARER ADVANTAGE". The Scotsman. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

The optional satellite navigation remains a Volvo-sourced system that is absurdly fiddly.

- ^ Simister, John (December 2006). "Land Rover Freelander". Evo. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

But it's good news for the new 'Freelander 2', based on the S-Max/S80/next-Mondeo platform, powered in the top model by a 229bhp Volvo straight-six

- ^ "Mitsubishi Motors announces alliance with Volvo". The Augusta Chronicle. 10 October 1999. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Miller, Scott (15 February 2001). "Volvo Might Sell Its Mitsubishi Stake Because of Daimler's Control of Firm". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Volvo säljer sitt innehav i Mitsubishi". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 11 April 2001. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "AB VOLVO TRANSFER REMAINING SHARES TO RENAULT S.A". Volvo. 9 February 2001. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Renault raises €3bn with part-sale of Volvo stake". The Daily Telegraph. 7 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ "Volvo in $1.1bn Nissan purchase". BBC News. BBC. 20 February 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ Pearson, David (12 December 2012). "Renault to Sell Rest of Its Volvo Stake". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ "Industrivärden strengthens its ownership position in Volvo". Industrivärden. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ "GKN's shares soar as it buys Volvo's aircraft engine business". The Guardian. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "China's Geely turns to Volvo trucks in latest Swedish venture". Reuters. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Matthew (12 February 2014). "Despite Raising Eyebrows, BlueLine Prices $252M PIK Toggle High Yield Bond Deal". Forbes. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Tran, Pierre (4 November 2016). "Volvo Launches RTD Sale, No Timetable". Defense News. Sightline Media Group. Retrieved 14 June 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Altmeyer, Cyril (24 May 2018). "Armament terrestre: Renault Trucks Defense (Volvo) devient Arquus" [Ground army: Renault Trucks Defense (Volvo) becomes Arquus]. L'Usine Nouvelle (in French). Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Volvo Group To Divest 75.1% Of Shares In WirelessCar Unit To Volkswagen". Markets Insider. 19 December 2018. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Volvo Group has completed the sale of shares in WirelessCar" (Press release). Volvo. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Okada, Emi; Yamada, Kohei; Fukao, Kosei (20 December 2019). "Isuzu tackles emerging rivals and R&D costs with Volvo tie-up". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Volvo Group and Isuzu Motors sign final agreements to form strategic alliance" (Press release). Volvo. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Volvo Group and Isuzu Motors complete UD Trucks transaction as part of the strategic alliance". volvogroup.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Steve (21 April 2020). "Volvo buying half of Daimler's fuel cell activities as firms form venture". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Carey, Nick (29 April 2021). "Daimler, Volvo seek huge cuts in hydrogen fuel cell costs by 2027". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Kane, Mark (19 December 2021). "Volvo, Daimler and Traton agree on JV charging network for trucks". InsideEVs. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Milence charging network accelerates Europe's shift to fossil-free road transport". UK Haulier. 8 December 2022. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Volvo investigates fossil fuel-free steel collaboration with SSAB". SSAB. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Volvo Cars to test fossil-free steel from SSAB's HYBRIT venture". Reuters. 16 June 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Truckmaker Volvo to buy Proterra's battery business for $210 mln". Reuters. 10 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Service Truck Magazine | Aug Sept 2024".

- ^ "Organization | Volvo Group". www.volvogroup.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "About us". Volvo Energy. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Our global presence". Volvo. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Our production facilities". Volvo. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Law, Christopher M. (July 2017). "Restructuring the Swedish manufacturing industry the case of the motor vehicle industry". Restructuring the Global Automobile Industry. Routledge Library Editions: The Automobile Industry. Vol. 4. Taylor & Francis. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-415-04712-8.

- ^ "Vår historia". volvogroup.com (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d Sandberg, Åke, ed. (2007). Enriching Production: Perspectives on Volvo's Uddevalla plant as an alternative to lean production. Avebury. pp. VIII–IX, 1–8. ISBN 978-1-85972-106-3.

- ^ a b Meredith, David (22 November 2017). "Milestone for Volvo's Brisbane plant". The West Australian. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Volvo celebrates 200,000 chassis produced at Borås factory". Coach & Bus Week. 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ivarsson, Inge; Alvstam, Claes G. (2007). "Global production and trade systems: the Volvo case". In Pellenbarg, Piet; Wever, Egbert (eds.). International Business Geography: Case Studies of Corporate Firms. Routledge. pp. 63–74. ISBN 978-0-203-93920-8.

- ^ a b Berggren, Christian (2019). Alternatives to Lean Production: Work Organization in the Swedish Auto Industry. Cornell University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-87546-317-9.

- ^ "Dig this history of Volvo evolving excavator range". Compact Equipment. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Volvo buys Nissan Diesel". Financial Times. 20 February 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Latimer, Cole (10 December 2013). "Terex sells trucks arm to Volvo". Australian Mining. Prime Creative Media. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Miller, Graham (31 December 2013). "Volvo buys Terex plant in Newhouse for $160m". Daily Record. Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Further job cuts at Terex truck firm in Motherwell". BBC. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Tuve plant". Volvo. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Volvo Trucks New River Valley plant". Volvo. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Blainville". Volvo. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Industrial organization". Arquus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Reman center". Volvo Trucks US. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Arvika". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Braås". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Eskilstuna". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Hallsberg". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Konz". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Hameln". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Belley". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Motherwell". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Changwon". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Bangalore". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Shanghai". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Pederneiras". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Shippensburg". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Linyi". Volvo Construction Equipment. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Nova Bus opens assembly plant in Plattsburgh, N.Y." Reliable Plant. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Wright, Robert (8 April 2022). "Volvo Trucks to take $423mn hit after halting work in Russia". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Volvo Annual Report 1999". .volvo.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "The Volvo Brand Name, Volvo Annual Report 1999". .volvo.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Academic Partner Program | Volvo Group". www.volvogroup.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "VIDÉO. Jean-Claude Van Damme fait le grand écart entre deux camions en marche arrière". HuffPost. 14 November 2013.

- ^ "VIDEOS. Jean-Claude Van Damme et Volvo : les secrets d'une pub qui cartonne". Le Parisien. 5 December 2013.

- ^ Nouvelle, L'Usine (7 December 2015). "L'industrie c'est fou : quand Volvo confie les clés du camion à une fille de 4 ans". usine nouvelle.

External links

[edit]- Official Volvo Group website

- Official Volvo website – for Volvo-branded companies.

Volvo

View on GrokipediaAB Volvo, known as the Volvo Group, is a Swedish multinational corporation headquartered in Gothenburg that manufactures trucks, buses, construction equipment, engines, and driveline solutions for heavy applications.[1] Founded in 1927 by Assar Gabrielsson and Gustaf Larson, the company initially produced passenger cars, beginning with the ÖV4 model, before divesting its automotive division in 1999 to focus on commercial vehicles; that entity now operates separately as Volvo Cars, majority-owned by China's Geely Holding Group.[2][3][4] With approximately 102,000 employees across nearly 180 markets, the Volvo Group emphasizes sustainable transport solutions and maintains production in 17 countries.[5] The brand gained renown for safety innovations, including the three-point seatbelt invented by engineer Nils Bohlin in 1959 and freely licensed to other manufacturers, which has saved millions of lives.[6]

History

Founding and early development (1927–1950)

AB Volvo was incorporated on August 10, 1926, as a subsidiary of the Swedish ball bearing manufacturer SKF, with Assar Gabrielsson appointed as managing director and Gustaf Larson as chief engineer.[7] The company aimed to produce durable automobiles suited to Sweden's harsh roads and climate, emphasizing safety and strength from inception.[2] The first prototype was tested in 1926, leading to the production of the inaugural series-manufactured car, the Volvo ÖV4 (also known as Jakob), which rolled off the assembly line at the Hisingen plant in Gothenburg on April 14, 1927.[2] Priced at 4,800 kronor, the ÖV4 featured a 2.0-liter inline-four engine producing 28 horsepower and a robust laminated steel body designed for longevity.[8] Initial car sales were modest, with 297 ÖV4 and PV4 variants (a saloon version) sold in the first year, totaling around 996 units produced by 1929.[8] Facing slow passenger car demand, Volvo pivoted toward commercial vehicles; the first truck, designated Type 1, entered production in 1928, proving more successful and helping achieve profitability by the third year through combined output of cars, trucks, and buses.[2] By 1929, total vehicle sales reached 1,383 units, including 27 exports, while the introduction of the six-cylinder PV651 model expanded the passenger lineup.[8] Trucks and buses dominated early production volumes, with models like the TR671 series taxis and PV652 saloon launched in 1930, coinciding with the purchase of the Hisingen factory for expanded operations.[8] The 1930s saw further growth, marked by the delivery of the 10,000th vehicle in 1932 and the debut of the first bus chassis, LV70B.[8] In 1935, Volvo floated shares on the Stockholm Stock Exchange and released the streamlined PV36 Carioca, priced at 8,500 kronor, which incorporated advanced features like independent front suspension.[8] Acquisitions bolstered capabilities, including engine supplier Pentaverken (later Volvo Penta) in 1935, enhancing powertrain development for both cars and trucks.[2] Exports grew, supported by the reputation for rugged reliability, though the Great Depression posed economic pressures. During World War II, Sweden's neutrality allowed continued production, primarily of trucks for civilian and military use, reaching the 50,000th vehicle milestone in 1941.[8] Postwar planning included the PV444 compact car, showcased in 1944 with 2,300 pre-orders, entering full production in 1947 and selling 10,181 units initially.[8] By 1950, variants like the PV444 B series and PV831/832 taxis were introduced, while truck lines evolved with heavier-duty models, setting the stage for broader internationalization; the PV60 truck production concluded that year.[8] Early emphasis on three-point safety belts in prototypes underscored Volvo's foundational commitment to occupant protection, though widespread adoption came later.[2]Post-war expansion and internationalization (1950–1990)

Following World War II, Volvo experienced significant domestic expansion in Sweden, driven by pent-up demand for civilian vehicles after wartime truck production. In 1950, the company acquired Bolinder-Munktell, laying the foundation for its construction equipment division. Car production surged with models like the PV444 series, reaching the 100,000th unit by 1956, while total annual output exceeded 50,000 vehicles by 1957. Truck manufacturing also grew, supported by Sweden's industrial recovery and export incentives.[2][9] Internationalization accelerated in the mid-1950s as Volvo targeted export markets to offset limited domestic capacity. Entry into the United States began in 1955 with PV444 exports, establishing over 100 dealers by 1956; the Amazon (P120/122) model, launched in 1956, became a key export success due to its durability and appeal in North America and Europe. Safety features, including standard padded dashboards in 1957 and the invention of the three-point seatbelt by engineer Nils Bohlin in 1959—offered patent-free to other manufacturers—enhanced Volvo's global reputation for engineering rigor, contributing to rising foreign sales.[9][9] The 1960s marked a shift toward overseas production to support export growth and reduce tariffs. In 1963, Volvo opened its first assembly plant outside Sweden in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, initially producing models like the Amazon for the North American market. Domestically, the Torslanda plant in Gothenburg commenced operations in 1964 with a capacity of 200,000 cars annually, enabling scaled production of the 140 series introduced in 1966. Further facilities included assembly in Alsemberg, Belgium (1960s), truck operations in Australia, and car manufacturing in Malaysia by 1968, reflecting strategic diversification amid rising global demand.[10][11][2] By the 1970s and 1980s, Volvo deepened its European footprint and ventured into emerging markets through acquisitions and new sites. A second truck plant opened in Belgium in 1977, alongside Swedish expansions like the Borås bus plant and Vara engine factory, bolstering truck and bus exports. The 240 series, launched in 1974, sustained car sales amid oil crises due to its fuel efficiency and safety. In 1980–1982, acquisitions of U.S.-based White Motor Corporation and Swedish firm AB Höglund & Co strengthened heavy truck capabilities, while a plant in Curitiba, Brazil, initiated local production. U.S. car exports rebounded strongly in the early 1980s, surpassing 100,000 units annually, as workforce grew from 8,500 in 1950 to 76,000 by the decade's start. These moves positioned Volvo as a multinational entity, with trucks comprising a growing share of international revenue.[2][12][13]Restructuring and divestitures (1990–2000)

In the early 1990s, AB Volvo encountered significant financial challenges, including operating losses and competitive pressures in its diversified operations, prompting efforts to restructure through strategic alliances. A proposed merger with Renault in 1993, intended to combine automotive businesses, was abandoned in December of that year after failing to gain sufficient shareholder and regulatory support, resulting in an estimated destruction of SEK 8.6 billion (approximately US$1.1 billion) in Volvo shareholder value due to market reactions and unresolved integration issues.[14] This setback highlighted the difficulties of cross-border consolidation amid differing corporate cultures and government influences on Renault, leading Volvo to pursue independent divestitures to reduce debt and refocus on core competencies. Throughout the decade, Volvo systematically shed non-core assets outside its vehicle and engine segments to streamline its portfolio and improve profitability. Organizational changes included a 1990 restructuring of Volvo North America Corporation, which involved management reshuffles and operational consolidations to address regional inefficiencies.[15] By the mid-1990s, the company had divested interests in areas such as pharmaceuticals and consumer products, including the separation of Procordia (its health care division) following Swedish government divestment in 1993, allowing Volvo to allocate resources toward industrial operations. These moves were driven by the need to counter declining margins in passenger cars, where high development costs and market saturation eroded returns compared to the more stable commercial vehicle sector. The period's pivotal divestiture occurred in 1999, when AB Volvo sold its passenger car operations—Volvo Cars—to Ford Motor Company for US$6.45 billion, a transaction announced in January and approved by shareholders on March 8.[16][17][18] This sale, motivated by the car division's underperformance relative to trucks and buses—where Volvo held leading global positions—enabled the company to eliminate substantial debt, fund investments in heavy vehicles, and concentrate on sectors with higher growth potential and margins. Post-divestiture, AB Volvo rebranded as the Volvo Group, emphasizing trucks, construction equipment, and engines, which marked a strategic shift toward industrial specialization amid globalization and industry consolidation.[19]Refocus on commercial vehicles and recent growth (2000–present)

Following the divestiture of its passenger car operations to Ford Motor Company in March 2000 for approximately SEK 50 billion, AB Volvo redirected its strategic emphasis toward commercial vehicles, encompassing trucks, buses, construction equipment, and related power solutions.[2] This refocus enabled the company to streamline resources and capitalize on its established expertise in heavy-duty transport and infrastructure machinery.[20] In 2001, Volvo Group acquired Renault Trucks and Mack Trucks from Renault for about SEK 25 billion, nearly doubling its global truck production capacity and enhancing market penetration in North America and Europe.[2] These acquisitions integrated complementary brands, with Mack focusing on North American heavy-haul applications and Renault Trucks strengthening European medium- and heavy-duty segments. Subsequent expansions included the 2007 establishment of a manufacturing plant in Kaluga, Russia, for trucks and construction equipment, and the 2008 acquisition of Shandong Lingong Construction Machinery (SDLG) in China, bolstering Volvo Construction Equipment's presence in emerging markets for wheel loaders and excavators.[2] Further consolidation occurred in 2013 with the purchase of Terex Corporation's off-highway hauler business for $160 million, adding rigid dump trucks to the construction portfolio, and a 45% stake in Dongfeng Commercial Vehicles (DFCV) with Dongfeng Motor Corporation, targeting China's truck market.[2] By 2016, the truck division reorganized into brand-specific units—Volvo Trucks, Mack Trucks, Renault Trucks, and UD Trucks—to optimize product development and regional strategies.[2] This period marked sustained revenue expansion, driven by rising global demand for commercial transport and infrastructure development. Net sales grew from SEK 291.5 billion in 2020 to SEK 553 billion in 2023, a compound annual growth rate exceeding 23%, fueled by higher vehicle volumes and service revenues.[21] Truck deliveries reached 246,272 units in 2023, up 6% from 2022, while construction equipment sales stood at 60,064 units despite market cyclicality.[21]| Year | Trucks (units) | Construction Equipment (units) | Buses (units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 232,769 | 86,885 | 9,731 |

| 2020 | 166,841 | 93,760 | 6,215 |

| 2021 | 202,458 | 99,871 | 4,522 |

| 2022 | 232,558 | 80,909 | 5,815 |

| 2023 | 246,272 | 60,064 | 5,773 |

Corporate Structure

Ownership and governance

AB Volvo, operating as Volvo Group, is a publicly traded company listed on Nasdaq Stockholm since 1935, with shares traded under the symbols VOLV A (class A shares) and VOLV B (class B shares). The company maintains a dual-class share structure, where class A shares confer ten votes per share and class B shares one vote, concentrating voting influence among A-share holders despite their smaller proportion of total capital.[23] This setup, common in Swedish firms, preserves strategic control with domestic institutional investors while allowing broader public participation through B shares. As of late 2024, approximately 88% of shares are held by institutional and large investors, with foreign ownership comprising a minority.[24][25] The largest shareholder is AB Industrivärden, a Swedish investment company, which holds about 9.6% of the capital but controls roughly 28% of voting rights through its A-share holdings.[26] Other notable owners include pension funds such as AMF Fonder AB (around 2.9% of capital) and Alecta (about 2.2%), alongside dispersed holdings by international institutions like BlackRock and Vanguard.[25] No entity possesses majority ownership, fostering a governance model reliant on consensus among key Swedish stakeholders rather than dominant external control. Geely Holding Group, owner of the separate Volvo Cars entity, maintains a minor stake insufficient for significant influence.[27] Governance follows the Swedish Corporate Governance Code, with the Board of Directors responsible for overall strategy, risk oversight, and executive remuneration, elected annually by shareholders at the annual general meeting.[28] Pär Boman has served as Chairman since March 2024, succeeding prior leadership to ensure continuity in industrial focus.[29] The board comprises ten members, including employee representatives and nominees from major shareholders like Industrivärden (e.g., Fredrik Persson), balancing independence with owner interests; key committees handle audit (chaired by Eric Elzvik), remuneration, and transformation initiatives.[30] Operational leadership rests with the Group Executive Board, chaired by President and CEO Martin Lundstedt, who has held the role since October 2015 and also serves on the board.[31] The executive team, numbering 11 members as of 2025, includes heads of divisions such as Roger Alm (Volvo Trucks), Melker Jernberg (Construction Equipment), and Jens Holtinger (Chief Technology Officer), reporting directly to the board on day-to-day execution and performance metrics.[31] This structure emphasizes long-term value creation, ethical standards, and alignment with shareholder priorities, with annual reports detailing compliance and deviations from the Code where applicable.[27]Organizational divisions and subsidiaries

The Volvo Group organizes its operations into distinct business areas focused on trucks, construction equipment, buses and coaches, marine and industrial engines, financial services, and emerging technologies such as autonomous solutions and energy systems. These divisions operate under dedicated leadership, with shared functions for research and development, purchasing, and manufacturing coordinated through entities like Group Trucks Technology and Group Trucks Operations. As of December 31, 2024, the trucks division reported net sales of SEK 360,610 million, construction equipment SEK 88,305 million, buses SEK 24,544 million, and Volvo Penta SEK 19,852 million, reflecting their relative scale within the group's industrial operations.[32][33] The trucks business area encompasses production and sales of heavy-duty and medium-duty vehicles under the Volvo Trucks, Mack Trucks, and Renault Trucks brands, supported by joint ventures including 45.6% ownership in VE Commercial Vehicles (for Eicher-branded trucks) and 45% in Dongfeng Commercial Vehicles. Key subsidiaries include Volvo Lastvagnar AB, which handles truck manufacturing and development in Sweden. This division integrates engine and transmission production across brands, with global R&D led by approximately 10,000 employees in Group Trucks Technology.[32][34][33] Volvo Construction Equipment manages articulated haulers, excavators, and wheel loaders primarily under the Volvo brand, alongside Rokbak for off-highway haulers and 70% ownership in Shandong Lingong Construction Machinery (SDLG) for compact equipment targeted at emerging markets. Operations are supported by subsidiaries such as Volvo Construction Equipment AB in Sweden. The buses and coaches area includes Volvo Buses for urban and intercity models, Prevost for premium touring coaches, and Nova Bus for North American transit vehicles, though Nova Bus underwent restructuring including factory closures by 2025.[32][34] Volvo Penta specializes in propulsion systems for marine, industrial, and off-road applications, operating as a fully integrated division with dedicated subsidiaries for engine production. Financial services are provided through Volvo Financial Services, a global arm offering leasing, loans, and insurance in approximately 50 countries, with a credit portfolio exceeding SEK 280 billion as of 2024 and headquartered in the United States. Additional subsidiaries handle group-wide functions, including Volvo Group Insurance Försäkrings AB and Volvo Group Venture Capital for strategic investments.[32][33][34] Joint ventures and partial ownerships extend the group's reach, such as 50% in cellcentric for fuel cell systems, 33.3% in Milence for electric charging infrastructure, and 45% in Flexis for last-mile delivery solutions established in 2024. These arrangements, totaling SEK 22.5 billion in investments by year-end 2024, complement core subsidiaries without full consolidation. AB Volvo directly or indirectly owns 289 legal entities, ensuring operational alignment across divisions while maintaining brand autonomy.[32][34]Products and Services

Trucks and buses

Volvo Trucks, a core division of the Volvo Group, began production with the LV Series 1 model in 1928, shortly after the company's founding, establishing a foundation for heavy-duty commercial vehicles emphasizing durability and safety.[35] The division now offers 16 truck models tailored for long-haul, distribution, construction, and specialized applications, with assembly occurring in 12 countries to serve operations in 130 markets worldwide.[36] In 2024, Volvo Trucks delivered 134,000 vehicles and maintained a 17.9% share of the global heavy-duty truck market (vehicles ≥16 tonnes), supported by approximately 11,500 employees and a network of 2,200 service points.[36][37] The division has led advancements in electrification, capturing 32% of the European heavy electric truck market and nearly 50% in North America as of early 2023, with sales expanding to 48 countries by 2024.[38][39] Volvo Buses, established as an independent division within the Volvo Group in 1968, traces its origins to the first bus prototype produced in 1928 on a modified truck chassis, followed by the introduction of diesel-powered models in 1945.[40][41] The division manufactures premium city buses, intercity buses, coaches, and chassis for bus rapid transit systems, prioritizing driver ergonomics, passenger safety, and low-emission technologies.[42] Operations span 85 countries with over 1,500 dealerships and workshops, including the Prevost subsidiary—acquired for its expertise in premium coaches since its founding in 1924—which supports more than 15,000 vehicles on North American roads.[42] Volvo Buses integrates Volvo Group resources for hybrid and fully electric models, aligning with commitments to the UN Global Compact for ethical and sustainable practices since 2001.[42] Both divisions contribute significantly to the Volvo Group's net sales of SEK 527 billion in 2024, with trucks forming the largest segment and buses advancing urban mobility solutions amid regulatory pushes for decarbonization.[32] Shared engineering focuses on first-principles safety features, such as advanced collision avoidance systems derived from decades of empirical testing, distinguishing Volvo products in competitive global markets.[43]Construction and mining equipment

Volvo Construction Equipment (Volvo CE), a business area within the Volvo Group, manufactures heavy machinery for construction sites and mining operations worldwide. Its product lineup includes wheel loaders, articulated haulers, hydraulic excavators, motor graders, asphalt and soil compactors, and pavers, with specialized variants adapted for mining environments such as rigid dump trucks and large-scale loaders for overburden removal and material handling.[44] The division traces its roots to 1832, when Johan Theofron Munktell established an engineering workshop in Eskilstuna, Sweden, initially focused on steam engines and agricultural machinery; this entity merged with Bolinder to form Bolinder-Munktell, which Volvo acquired in 1950 to enter the construction sector.[45][46] Key early innovations include the 1954 introduction of the H10 wheel loader, marking Volvo's first foray into loader production, and the 1966 launch of the DR 631, the world's inaugural articulated hauler designed for rugged terrain transport in construction and mining.[45][47] Volvo CE's mining equipment emphasizes durability and productivity in surface operations, with articulated haulers like the A-series models capable of payloads exceeding 50 tons and rigid haulers for high-volume ore transport; these machines integrate Volvo's proprietary engine technology for fuel efficiency and reduced emissions.[44] The company maintains manufacturing facilities globally, including a North American plant in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, operational since 1974 for compaction equipment and expanded for broader production.[48] In recent performance, Volvo CE delivered 16,987 machines in the second quarter of 2025, reflecting steady demand amid global infrastructure projects, though the division contends with cyclical market fluctuations tied to commodity prices and construction activity.[49] As part of the Volvo Group's SEK 527 billion net sales in 2024, Volvo CE contributes significantly to the corporation's construction segment, holding a competitive position among top global manufacturers with emphasis on technological integration for operator safety and machine uptime.[32][50]Engines and power solutions

Volvo Group's engines and power solutions are primarily developed and supplied through its subsidiary Volvo Penta, which specializes in marine, industrial, and power generation applications.[5] Established as an independent entity in 1907 in Skövde, Sweden, with the production of its first marine diesel engine, the B1, Volvo Penta was acquired by Volvo in 1935 when the company purchased Pentaverken, its engine supplier.[51] Today, Volvo Penta offers a range of diesel engines characterized by high torque at low RPM, fuel efficiency, and compliance with stringent emission standards such as Stage V for off-road use.[52] In marine applications, Volvo Penta provides propulsion systems including inboard engines like the D4 and D6 series, designed for powerboats, yachts, and commercial vessels, emphasizing durability and performance in harsh saltwater environments.[53] These engines integrate with technologies such as the IPS (Inboard Performance System) for enhanced maneuverability and efficiency.[51] For industrial uses, Volvo Penta engines power off-highway equipment, irrigation systems, and water management, with models optimized for reliability in agriculture, mining, and municipal operations.[54] Power generation solutions from Volvo Penta include stationary engines for backup and prime power, supporting capacities from small-scale to large industrial needs, often paired with electronic controls for remote monitoring and low emissions. The division is expanding into alternative power sources, including hydrogen fuel cells suitable for trucks, buses, and marine applications, as well as electric and hybrid systems to meet sustainability demands.[55] These advancements build on Volvo Penta's legacy of innovation, such as pioneering sterndrive systems in the mid-20th century, while maintaining a focus on robust, low-maintenance designs.[51]Financial and support services

Volvo Financial Services (VFS), the captive finance subsidiary of the Volvo Group, offers customized financing, leasing, and insurance solutions for trucks, buses, construction equipment, and marine engines to facilitate customer acquisitions and operational continuity.[56] Operating across more than 50 markets with over 1,500 employees, VFS emphasizes flexible terms that align with business cash flows, including options for wholesale financing to dealers and retail contracts for end-users.[57] Service financing products cover maintenance and repair costs, enabling extended vehicle utilization without upfront capital burdens.[33] Support services complement these financial offerings by prioritizing vehicle uptime and operational efficiency through proactive and reactive interventions. The Volvo Action Service provides round-the-clock roadside assistance, towing, and emergency repairs, supported by a dealer network exceeding 400 locations in North America.[58] For construction equipment, real-time technical support leverages live video feeds and mobile diagnostics to enable remote troubleshooting by expert technicians, minimizing on-site downtime.[59] Additional programs include preventive maintenance contracts, genuine parts distribution, and telematics-based fleet monitoring to predict failures and optimize fuel efficiency across global operations.[5]Innovations and Technology

Pioneering advancements in safety and efficiency

Volvo's commitment to safety originated with the development of the modern three-point seat belt by engineer Nils Bohlin in 1959, a design patented by the company but freely licensed to all manufacturers to maximize its life-saving potential, an action credited with preventing over one million fatalities worldwide.[6][60] This innovation built on earlier two-point belts but introduced a diagonal upper strap anchored to the opposite side, distributing crash forces across the stronger pelvis and shoulder while allowing controlled body movement to avoid submarining or ejection.[61] In commercial vehicles, Volvo pioneered the safety cab for trucks in 1977, featuring a reinforced structure with energy-absorbing zones to protect the driver during frontal collisions by deforming in a controlled manner rather than shattering.[62] The company introduced anti-lock braking systems (ABS) for heavy trucks in 1985, enabling wheels to maintain traction during emergency stops on varied surfaces and reducing jackknifing risks, a technology that became an industry standard after initial adoption in models like the F10 and F12.[62] Further advancements included the front underride guard in 1996, designed to prevent smaller vehicles from sliding under truck trailers during rear-end impacts, enhancing compatibility in mixed traffic.[62] On efficiency, Volvo integrated turbo-compound technology into its D13 engine for trucks starting in the early 2010s, recovering exhaust energy to boost power output by up to 50 horsepower and improve fuel economy by 3-5% compared to conventional turbocharged diesels, through a power turbine linked directly to the crankshaft.[63] Aerodynamic optimizations, such as those in the 2024 Volvo VNL tractor, achieved up to 10% better fuel efficiency via streamlined cab designs, side fairings, and gap reducers that minimize drag at highway speeds, validated through wind tunnel testing and real-world fleet data.[64] These efforts extended to transmissions like the I-Shift, refined in 2024 with 30% faster shift speeds to optimize engine load and reduce fuel consumption by maintaining peak torque bands.[65] In construction equipment, Volvo introduced load-sensing hydraulic systems in excavators during the 1980s, which adjust pump output based on demand to lower energy use by up to 20% during partial loads, pioneering variable displacement pumps that superseded fixed-flow designs for better cycle times and reduced diesel burn.[66] The company's participation in the U.S. SuperTruck 2 program, culminating in 2023, demonstrated a 100%+ freight efficiency gain in prototype heavy-duty trucks through integrated hybrid powertrains and waste heat recovery, exceeding Department of Energy targets via combined engine, aerodynamic, and tire innovations.[67]Electrification, autonomy, and sustainable technologies

Volvo Group initiated series production of battery-electric trucks with gross vehicle weights up to 27 tons in 2019, establishing leading market shares in Europe and North America for zero-emission commercial vehicles.[68] The company expanded its electrification portfolio with models such as the VNR Electric, which accumulated 15 million zero-tailpipe-emission miles in North American customer operations by April 2025.[69] In September 2024, Volvo announced the launch of a long-range FH Electric variant capable of up to 600 km on a single charge, scheduled for production in 2025, targeting heavy-duty transport applications.[70] Electrification extends to buses and construction equipment, supported by joint ventures including battery and fuel cell development with Daimler Truck.[71] Volvo Autonomous Solutions, a dedicated division, develops hub-to-hub autonomous transport systems for trucks, emphasizing safety through virtual driver technology.[72] Key partnerships include a 2021 collaboration with Aurora for the Volvo VNL Autonomous truck, integrating driverless capabilities at Volvo's New River Valley plant.[73] Additional alliances, such as with Waabi, focus on AI-driven autonomy for scalable deployment.[74] Operational milestones include autonomous hauling of over 1 million tonnes at Brønnøy Kalk mine using seven FH trucks by May 2025, and the December 2024 start of driverless operations for DHL Supply Chain in Texas, demonstrating practical freight applications.[75][76] Sustainable technologies encompass hydrogen fuel cells, alongside electrification, as part of a multi-pathway decarbonization strategy to address varying operational needs.[77] The company adheres to Science Based Targets for emission reductions aligned with climate science, committing to prolong product lifecycles through reuse, recycling, and minimized resource impacts.[78][79] Volvo's 2019-2020 strategic update integrated sustainability across climate, resources, and people, prioritizing replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy sources in operations and products.[80] These efforts aim for zero-emission transport solutions, with investments in clean power technologies projected to boost lifecycle revenues from electrified vehicles by over 50%.[81]Global Operations

Manufacturing facilities and supply chain

Volvo Group maintains manufacturing facilities in 18 countries, encompassing production of trucks, buses, construction equipment, engines, and transmissions, with 19 facilities in Europe alone and additional assembly operations supported by independent partners at 10 global locations.[82] Major hubs include the Tuve plant in Göteborg, Sweden, which assembles Volvo trucks, and the Köping facility in Sweden for engines and transmissions.[83] In North America, the company operates 16 manufacturing and remanufacturing sites across the United States, Canada, and Mexico, highlighted by the New River Valley Plant in Dublin, Virginia—the largest global facility for Volvo Trucks, producing all heavy-duty models sold in the region.[84][85] Other key European sites feature the Gent plant in Belgium for truck assembly, Blainville and Bourg-en-Bresse in France for Volvo and Renault Trucks respectively, and facilities in Germany (Konz-Könen for construction equipment) and the United Kingdom (Motherwell for construction machinery).[83] Outside Europe, production occurs in Brazil (Curitiba for trucks), India (Bangalore for construction equipment), and South Korea, with recent expansions including a $261 million investment announced in June 2025 to bolster crawler excavator output at sites in Sweden, Shippensburg (Pennsylvania, USA), and South Korea.[86][87] A planned battery production facility in Sweden faces delays, with high-volume output now projected several years beyond the original 2025 target due to market and technical factors.[88] The supply chain emphasizes rigorous supplier standards, including compliance with the Volvo Group Supply Partner Code of Conduct for human rights, environmental performance, and anti-corruption measures, alongside evaluations using tools like the Global MMOG/LE for logistics efficiency.[89] Sustainability initiatives include sourcing fossil-free steel since 2022, produced via hydrogen-based reduction to cut CO2 emissions, as part of broader net-zero ambitions across the chain.[90] Suppliers must report material data through the International Material Data System (IMDS) and adhere to Volvo's restricted substances lists to ensure product quality and minimize downtime in aftermarket services.[89] These practices support proactive collaboration for cost reduction and innovation, though global disruptions have prompted inventory visibility enhancements via data platforms for spare parts distribution.[91]Workforce and international presence

As of December 31, 2024, the Volvo Group employed 102,000 people globally.[32] By June 30, 2025, this figure had risen to 103,201, including temporary employees and consultants.[92] The workforce supports operations across trucks, buses, construction equipment, and engines, with a focus on manufacturing, assembly, research, and sales.[1] In North America, which accounted for 29% of 2024 sales, the company employs over 19,600 individuals across 16 manufacturing and remanufacturing sites in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.[84] Europe remains the core region, featuring 19 production facilities—primarily in Sweden—and key markets including France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Sweden itself.[82] Volvo Group's international footprint extends to production in 18 countries and distribution in nearly 180 markets, enabling localized assembly and adaptation to regional demands.[82] Notable facilities include assembly plants in India (such as Hosakote near Bangalore, operational since 1998 for truck production), Australia, and additional sites in Asia, Africa, and South America to serve emerging markets.[93] This decentralized structure supports supply chain resilience and reduces dependency on any single region, though it exposes the company to varying labor regulations and geopolitical risks.[5]Financial Performance

Historical trends and key metrics

AB Volvo's financial performance has historically exhibited cyclical patterns closely aligned with global economic cycles, commodity prices, and infrastructure spending, given its core businesses in trucks, construction equipment, buses, and engines. Founded in 1927, the company initially diversified into automobiles but refocused on commercial vehicles after divesting its passenger car division to Ford in 1999 for $6.45 billion, enabling targeted growth in higher-margin heavy-duty segments. Net sales expanded steadily from the early 2000s amid globalization and emerging market demand, particularly in Asia and North America, though punctuated by downturns during the 2008-2009 financial crisis (when truck sales volumes fell over 50% globally) and the 2020 COVID-19 disruptions. Recovery phases, such as post-2010, saw revenue compound annually at around 5-7% through volume growth and operational efficiencies, culminating in record highs in 2022-2023 driven by supply chain normalization and pent-up demand.[94] Key metrics underscore this trajectory, with net sales peaking at SEK 553 billion in 2023 before contracting to SEK 527 billion in 2024 amid softening demand and inventory adjustments in trucks and construction equipment. Operating income followed suit, reaching SEK 66 billion in 2024 with margins stabilizing around 12-13% post-recovery, reflecting cost controls and pricing power in premium segments despite raw material volatility. Net income for 2023 stood at approximately SEK 40 billion (equivalent to $3.78 billion), bolstered by higher volumes, though earlier years like 2020 saw sharp declines to under SEK 20 billion due to pandemic-related halts. Sales volumes in trucks, the largest contributor (over 60% of revenue), hit an all-time high of 145,195 units in 2022, up 19% from 122,525 in 2021, before moderating in subsequent years.[32][94][95]| Year | Net Sales (SEK billion) | Operating Income (SEK billion) | Truck Deliveries (units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | ~340 | ~25 | ~110,000 |

| 2021 | ~372 | ~32 | 122,525 |

| 2022 | ~482 | ~53 | 145,195 |

| 2023 | 553 | ~82 | ~140,000 |

| 2024 | 527 | 66 | ~130,000 |

Recent results and market challenges (2020–2025)

Volvo Cars experienced a recovery from the COVID-19 disruptions in 2020, with global retail sales volumes increasing from approximately 661,000 units in 2020 to 698,000 in 2021 amid supply chain constraints. Revenue grew from SEK 249.9 billion in 2020 to SEK 262.8 billion in 2021. By 2022, sales volumes dipped to around 620,000 units due to semiconductor shortages and geopolitical tensions affecting production, though revenue rose to SEK 282.0 billion supported by pricing adjustments. In 2023, volumes rebounded to 708,000 units and revenue to SEK 330.1 billion, reflecting improved supply chains and demand for electrified models. The company achieved record performance in 2024, with global sales reaching 763,389 vehicles—an 8% increase from 2023—and revenue hitting SEK 400.2 billion for the first time, driven by strong sales in Europe and the US alongside higher average selling prices.[97][98] Entering 2025, Volvo Cars faced heightened market challenges, including softening demand for electric vehicles (EVs), intensified competition from lower-cost Chinese manufacturers, and macroeconomic pressures such as inflation and potential tariffs on imports linked to its Chinese parent company Geely. Global retail sales declined, with August volumes down 9% year-over-year to 48,029 units and May sales plunging 12%, attributed to tariff uncertainties, rising material costs, and an SUV-dominated market where Volvo's sedan lineup struggled. In response, the company launched an SEK 18 billion cost and cash action plan in Q1 2025, targeting reduced fixed costs and inventory optimization.[99][100][101] Financial results in 2025 reflected these headwinds: Q1 operating income (EBIT) stood at SEK 1.9 billion with wholesales down due to strategic volume management, but Q2 swung to a SEK -10.0 billion loss amid lower volumes and pricing pressures. Q3 showed partial recovery with EBIT of SEK 6.4 billion and a 7.4% margin, though overall the year was described as turbulent by CEO Jim Rowan, with expectations of industry-wide price cuts and stagnant car demand growth. US sales exemplified the slump, dropping 9% to 26,021 units in Q3.[101][102][103] A key strategic shift addressed EV market realities: In September 2024, Volvo adjusted its electrification targets from 100% fully electric sales by 2030 to 90-100% electrified (including plug-in hybrids) by 2030 and 50-60% by 2025, citing slower-than-expected consumer adoption, subsidy reductions in Europe, and infrastructure gaps rather than abandoning sustainability goals. This flexibility aimed to balance profitability amid hybrid demand resurgence, though it drew criticism for diluting earlier ambitions amid competitive pressures from Tesla and BYD. The company pledged five new products despite trade challenges, focusing on premium positioning to revive US retail sales by 60%.[104][105][106]| Year | Global Sales Volume (units) | Revenue (SEK billion) |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | ~698,000 | 262.8 |

| 2022 | ~620,000 | 282.0 |

| 2023 | 708,000 | 330.1 |

| 2024 | 763,389 | 400.2 |

Controversies and Criticisms

Emissions compliance and regulatory penalties

In the late 1990s, Volvo's truck division, part of Volvo Group, entered into a landmark settlement with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) over violations involving diesel engine emissions controls. The agreement, announced on October 22, 1998, imposed an $83.4 million civil penalty—the largest ever at the time for environmental law violations—on Volvo Truck Corporation and other manufacturers for equipping heavy-duty diesel engines with devices that defeated emissions standards during normal operation while passing lab tests.[107] This case highlighted early regulatory scrutiny on real-world versus laboratory emissions discrepancies, requiring engine redesigns projected to reduce nationwide nitrogen oxide emissions by 75 million tons by 2025.[108] Subsequent enforcement actions targeted ongoing non-compliance in Volvo Group's engine production. In 2014, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld penalties against Volvo for failing to meet EPA standards on heavy-duty diesel engines, ordering payment of approximately SEK 508 million (about $76 million USD at the time) plus interest.[109] The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case in 2015, affirming a $62 million portion of the penalty related to emissions exceedances.[110] These rulings stemmed from consent decrees where Volvo had committed to emissions reductions but fell short, underscoring causal links between inadequate selective catalytic reduction systems and higher pollutant outputs. Smaller-scale violations persisted, such as a 2022 California Air Resources Board settlement fining Volvo Group North America $21,645 for emission warranty breaches on affected vehicles.[111] For Volvo Cars, the passenger vehicle arm independent from Volvo Group since 2010, emissions controversies have centered on diesel models amid the broader post-2015 "Dieselgate" revelations, though without equivalent regulatory penalties. Independent testing revealed certain Volvo diesels, such as the S60, exceeding European NOx limits in real-driving conditions by factors of up to several times lab approvals, prompting allegations of software-based defeat devices. This led to civil class-action claims in jurisdictions like the UK, where law firms pursued compensation for owners of 2007–2020 models, asserting misleading emissions data influenced purchase decisions.[112] Unlike Volkswagen's billions in EPA and EU fines for deliberate cheating, Volvo Cars faced no comparable government sanctions; responses included voluntary software recalls to align real-world performance with standards, avoiding formal findings of systematic fraud.[113] Recent fleet-wide CO2 compliance for Volvo Cars reflects proactive adaptation rather than penalties. Positioned ahead of the EU's 2025 target of 93.6 g/km through high electric vehicle penetration, Volvo has pooled excess credits with partners like Suzuki to offset their deficits, averting fines under the regulation's averaging mechanism.[114] Company leadership opposed proposed EU delays to stricter targets, citing achievable compliance via electrification, with no penalties incurred to date despite industry-wide pressures potentially totaling €15 billion.[115][116] This contrasts with laggards reliant on pooling or regulatory relief, emphasizing Volvo's empirical progress in reducing tailpipe emissions through hybrid and battery-electric shifts.Ethical sourcing, geopolitical involvement, and data security issues