Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bump function

View on Wikipedia

In mathematical analysis, a bump function (also called a test function) is a function on a Euclidean space which is both smooth (in the sense of having continuous derivatives of all orders) and compactly supported. The set of all bump functions with domain forms a vector space, denoted or The dual space of this space endowed with a suitable topology is the space of distributions.

Examples

[edit]

The function given by

is an example of a bump function in one dimension. Note that the support of this function is the closed interval . In fact, by definition of support, we have that , where the closure is taken with respect the Euclidean topology of the real line. The proof of smoothness follows along the same lines as for the related function discussed in the Non-analytic smooth function article. This function can be interpreted as the Gaussian function scaled to fit into the unit disc: the substitution corresponds to sending to

A simple example of a (square) bump function in variables is obtained by taking the product of copies of the above bump function in one variable, so

A radially symmetric bump function in variables can be formed by taking the function defined by . This function is supported on the unit ball centered at the origin.

For another example, take an that is positive on and zero elsewhere, for example

- .

Smooth transition functions

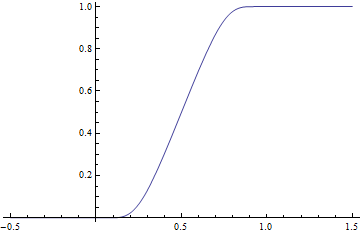

Consider the function

defined for every real number x.

The function

has a strictly positive denominator everywhere on the real line, hence g is also smooth. Furthermore, g(x) = 0 for x ≤ 0 and g(x) = 1 for x ≥ 1, hence it provides a smooth transition from the level 0 to the level 1 in the unit interval [0, 1]. To have the smooth transition in the real interval [a, b] with a < b, consider the function

For real numbers a < b < c < d, the smooth function

equals 1 on the closed interval [b, c] and vanishes outside the open interval (a, d), hence it can serve as a bump function.

Caution must be taken since, as example, taking , leads to:

which is not an infinitely differentiable function (so, is not "smooth"), so the constraints a < b < c < d must be strictly fulfilled.

Some interesting facts about the function:

Are that make smooth transition curves with "almost" constant slope edges (a bump function with true straight slopes is portrayed this Another example).

A proper example of a smooth Bump function would be:

A proper example of a smooth transition function will be:

where could be noticed that it can be represented also through Hyperbolic functions:

Existence of bump functions

[edit]

It is possible to construct bump functions "to specifications". Stated formally, if is an arbitrary compact set in dimensions and is an open set containing there exists a bump function which is on and outside of Since can be taken to be a very small neighborhood of this amounts to being able to construct a function that is on and falls off rapidly to outside of while still being smooth.

Bump functions defined in terms of convolution

The construction proceeds as follows. One considers a compact neighborhood of contained in so The characteristic function of will be equal to on and outside of so in particular, it will be on and outside of This function is not smooth however. The key idea is to smooth a bit, by taking the convolution of with a mollifier. The latter is just a bump function with a very small support and whose integral is Such a mollifier can be obtained, for example, by taking the bump function from the previous section and performing appropriate scalings.

Bump functions defined in terms of a function with support

An alternative construction that does not involve convolution is now detailed. It begins by constructing a smooth function that is positive on a given open subset and vanishes off of [1] This function's support is equal to the closure of in so if is compact, then is a bump function.

Start with any smooth function that vanishes on the negative reals and is positive on the positive reals (that is, on and on where continuity from the left necessitates ); an example of such a function is for and otherwise.[1] Fix an open subset of and denote the usual Euclidean norm by (so is endowed with the usual Euclidean metric). The following construction defines a smooth function that is positive on and vanishes outside of [1] So in particular, if is relatively compact then this function will be a bump function.

If then let while if then let ; so assume is neither of these. Let be an open cover of by open balls where the open ball has radius and center Then the map defined by is a smooth function that is positive on and vanishes off of [1] For every let where this supremum is not equal to (so is a non-negative real number) because the partial derivatives all vanish (equal ) at any outside of while on the compact set the values of each of the (finitely many) partial derivatives are (uniformly) bounded above by some non-negative real number.[note 1] The series converges uniformly on to a smooth function that is positive on and vanishes off of [1] Moreover, for any non-negative integers [1] where this series also converges uniformly on (because whenever then the th term's absolute value is ). This completes the construction.

As a corollary, given two disjoint closed subsets of the above construction guarantees the existence of smooth non-negative functions such that for any if and only if and similarly, if and only if then the function is smooth and for any if and only if if and only if and if and only if [1] In particular, if and only if so if in addition is relatively compact in (where implies ) then will be a smooth bump function with support in

Properties and uses

[edit]While bump functions are smooth, the identity theorem prohibits their being analytic unless they vanish identically. Bump functions are often used as mollifiers, as smooth cutoff functions, and to form smooth partitions of unity. They are the most common class of test functions used in analysis. The space of bump functions is closed under many operations. For instance, the sum, product, or convolution of two bump functions is again a bump function, and any differential operator with smooth coefficients, when applied to a bump function, will produce another bump function.

If the boundaries of the Bump function domain is to fulfill the requirement of "smoothness", it has to preserve the continuity of all its derivatives, which leads to the following requirement at the boundaries of its domain:

The Fourier transform of a bump function is a (real) analytic function, and it can be extended to the whole complex plane: hence it cannot be compactly supported unless it is zero, since the only entire analytic bump function is the zero function (see Paley–Wiener theorem and Liouville's theorem). Because the bump function is infinitely differentiable, its Fourier transform must decay faster than any finite power of for a large angular frequency [2] The Fourier transform of the particular bump function from above can be analyzed by a saddle-point method, and decays asymptotically as for large [3]

See also

[edit]- Cutoff function – Integration kernels for smoothing out sharp features

- Laplacian of the indicator – Limit of sequence of smooth functions

- Non-analytic smooth function – Mathematical functions which are smooth but not analytic

- Schwartz space – Function space of all functions whose derivatives are rapidly decreasing

Citations

[edit]- ^ The partial derivatives are continuous functions so the image of the compact subset is a compact subset of The supremum is over all non-negative integers where because and are fixed, this supremum is taken over only finitely many partial derivatives, which is why

- ^ a b c d e f g Nestruev 2020, pp. 13–16.

- ^ K. O. Mead and L. M. Delves, "On the convergence rate of generalized Fourier expansions," IMA J. Appl. Math., vol. 12, pp. 247–259 (1973) doi:10.1093/imamat/12.3.247.

- ^ Steven G. Johnson, Saddle-point integration of C∞ "bump" functions, arXiv:1508.04376 (2015).

References

[edit]- Nestruev, Jet (10 September 2020). Smooth Manifolds and Observables. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 220. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-45649-8. OCLC 1195920718.

![{\displaystyle [-1,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51e3b7f14a6f70e614728c583409a0b9a8b9de01)

![{\displaystyle (-\infty ,0]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0241c015ef4c611c9c9aeafb395e7c4a16178405)

![{\displaystyle h~:=~{\frac {f_{A}}{f_{A}+f_{B}}}:\mathbb {R} ^{n}\to [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f5098be32605f8c2a579bc3bd9821e73a36f8c40)