Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Analytic function

View on Wikipedia| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Basic theory |

| Complex functions |

| Theorems |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In mathematics, an analytic function is a function that is locally given by a convergent power series. There exist both real analytic functions and complex analytic functions. Functions of each type are infinitely differentiable, but complex analytic functions exhibit properties that do not generally hold for real analytic functions.

A function is analytic if and only if for every in its domain, its Taylor series about converges to the function in some neighborhood of . This is stronger than merely being infinitely differentiable at , and therefore having a well-defined Taylor series; the Fabius function provides an example of a function that is infinitely differentiable but not analytic.

Definitions

[edit]Formally, a function is real analytic on an open set in the real line if for any one can write

in which the coefficients are real numbers and the series is convergent to for in a neighborhood of .

Alternatively, a real analytic function is an infinitely differentiable function such that the Taylor series at any point in its domain

converges to for in a neighborhood of pointwise.[a] The set of all real analytic functions on a given set is often denoted by , or just by if the domain is understood.

A function defined on some subset of the real line is said to be real analytic at a point if there is a neighborhood of on which is real analytic.

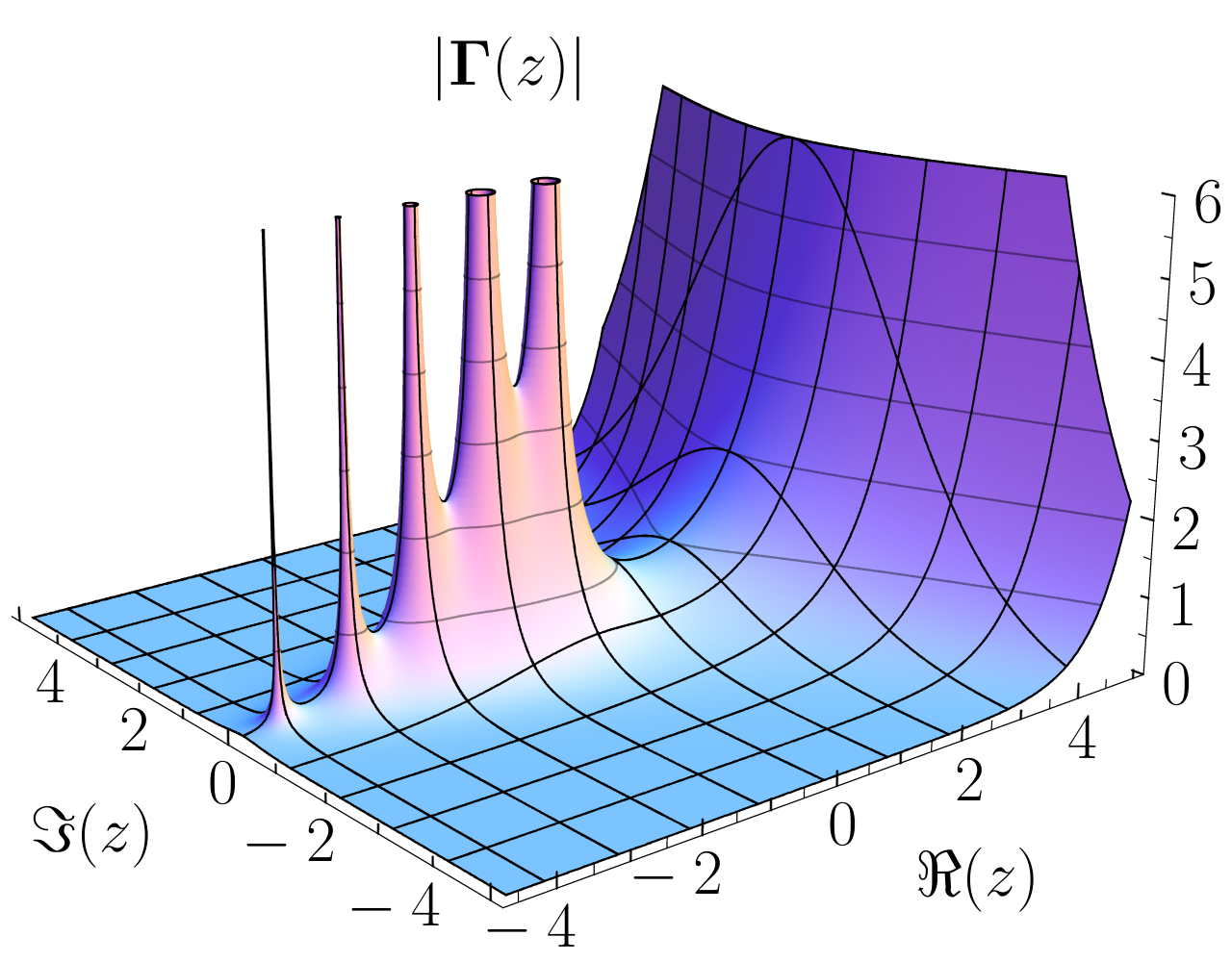

The definition of a complex analytic function is obtained by replacing, in the definitions above, "real" with "complex" and "real line" with "complex plane". A function is complex analytic if and only if it is holomorphic i.e. it is complex differentiable. For this reason the terms "holomorphic" and "analytic" are often used interchangeably for such functions.[1]

In complex analysis, a function is called analytic in an open set "U" if it is (complex) differentiable at each point in "U" and its complex derivative is continuous on "U".[2]

Examples

[edit]Typical examples of analytic functions are

- The following elementary functions:

- All polynomials: if a polynomial has degree n, any terms of degree larger than n in its Taylor series expansion must immediately vanish to 0, and so this series will be trivially convergent. Furthermore, every polynomial is its own Maclaurin series.

- The exponential function is analytic. Any Taylor series for this function converges not only for x close enough to x0 (as in the definition) but for all values of x (real or complex).

- The trigonometric functions, logarithm, and the power functions are analytic on any open set of their domain.

- Most special functions (at least in some range of the complex plane):

Typical examples of functions that are not analytic are

- The absolute value function when defined on the set of real numbers or complex numbers is not everywhere analytic because it is not differentiable at 0.

- Piecewise defined functions (functions given by different formulae in different regions) are typically not analytic where the pieces meet.

- The complex conjugate function z → z* is not complex analytic, although its restriction to the real line is the identity function and therefore real analytic, and it is real analytic as a function from to .

- Other non-analytic smooth functions, and in particular any smooth function with compact support, i.e. , cannot be analytic on .[3]

Alternative characterizations

[edit]The following conditions are equivalent:

- is real analytic on an open set .

- There is a complex analytic extension of to an open set which contains .

- is smooth and for every compact set there exists a constant such that for every and every non-negative integer the following bound holds[4]

Complex analytic functions are exactly equivalent to holomorphic functions, and are thus much more easily characterized.

For the case of an analytic function with several variables (see below), the real analyticity can be characterized using the Fourier–Bros–Iagolnitzer transform.

In the multivariable case, real analytic functions satisfy a direct generalization of the third characterization.[5] Let be an open set, and let . Then is real analytic on if and only if and for every compact there exists a constant such that for every multi-index the following bound holds[6]

Properties of analytic functions

[edit]- The sums, products, and compositions of analytic functions are analytic.

- The reciprocal of an analytic function that is nowhere zero is analytic, as is the inverse of an invertible analytic function whose derivative is nowhere zero. (See also the Lagrange inversion theorem.)

- Any analytic function is smooth, that is, infinitely differentiable. The converse is not true for real functions; in fact, in a certain sense, the real analytic functions are sparse compared to all real infinitely differentiable functions. For the complex numbers, the converse does hold, and in fact any function differentiable once on an open set is analytic on that set (see "analyticity and differentiability" below).

- For any open set , the set A(Ω) of all analytic functions is a Fréchet space with respect to the uniform convergence on compact sets. The fact that uniform limits on compact sets of analytic functions are analytic is an easy consequence of Morera's theorem. The set of all bounded analytic functions with the supremum norm is a Banach space.

A polynomial cannot be zero at too many points unless it is the zero polynomial (more precisely, the number of zeros is at most the degree of the polynomial). A similar but weaker statement holds for analytic functions. If the set of zeros of an analytic function ƒ has an accumulation point inside its domain, then ƒ is zero everywhere on the connected component containing the accumulation point. In other words, if (rn) is a sequence of distinct numbers such that ƒ(rn) = 0 for all n and this sequence converges to a point r in the domain of D, then ƒ is identically zero on the connected component of D containing r. This is known as the identity theorem.

Also, if all the derivatives of an analytic function at a point are zero, the function is constant on the corresponding connected component.

These statements imply that while analytic functions do have more degrees of freedom than polynomials, they are still quite rigid.

Analyticity and differentiability

[edit]As noted above, any analytic function (real or complex) is infinitely differentiable (also known as smooth, or ). (Note that this differentiability is in the sense of real variables; compare complex derivatives below.) There exist smooth real functions that are not analytic: see non-analytic smooth function. In fact there are many such functions.

The situation is quite different when one considers complex analytic functions and complex derivatives. It can be proved that any complex function differentiable (in the complex sense) in an open set is analytic. Consequently, in complex analysis, the term analytic function is synonymous with holomorphic function.

Real versus complex analytic functions

[edit]Real and complex analytic functions have important differences (one could notice that even from their different relationship with differentiability). Analyticity of complex functions is a more restrictive property, as it has more restrictive necessary conditions and complex analytic functions have more structure than their real-line counterparts.[7]

According to Liouville's theorem, any bounded complex analytic function defined on the whole complex plane is constant. The corresponding statement for real analytic functions, with the complex plane replaced by the real line, is clearly false; this is illustrated by

Also, if a complex analytic function is defined in an open ball around a point x0, its power series expansion at x0 is convergent in the whole open ball (holomorphic functions are analytic). This statement for real analytic functions (with open ball meaning an open interval of the real line rather than an open disk of the complex plane) is not true in general; the function of the example above gives an example for x0 = 0 and a ball of radius exceeding 1, since the power series 1 − x2 + x4 − x6... diverges for |x| ≥ 1.

Any real analytic function on some open set on the real line can be extended to a complex analytic function on some open set of the complex plane. However, not every real analytic function defined on the whole real line can be extended to a complex function defined on the whole complex plane. The function f(x) defined in the paragraph above is a counterexample, as it is not defined for x = ±i. This explains why the Taylor series of f(x) diverges for |x| > 1, i.e., the radius of convergence is 1 because the complexified function has a pole at distance 1 from the evaluation point 0 and no further poles within the open disc of radius 1 around the evaluation point.

Analytic functions of several variables

[edit]One can define analytic functions in several variables by means of power series in those variables (see power series). Analytic functions of several variables have some of the same properties as analytic functions of one variable. However, especially for complex analytic functions, new and interesting phenomena show up in 2 or more complex dimensions:

- Zero sets of complex analytic functions in more than one variable are never discrete. This can be proved by Hartogs's extension theorem.

- Domains of holomorphy for single-valued functions consist of arbitrary (connected) open sets. In several complex variables, however, only some connected open sets are domains of holomorphy. The characterization of domains of holomorphy leads to the notion of pseudoconvexity.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This implies uniform convergence as well in a (possibly smaller) neighborhood of .

- ^ Churchill; Brown; Verhey (1948). Complex Variables and Applications. McGraw-Hill. p. 46. ISBN 0-07-010855-2.

A function f of the complex variable z is analytic at point z0 if its derivative exists not only at z but at each point z in some neighborhood of z0. It is analytic in a region R if it is analytic at every point in R. The term holomorphic is also used in the literature to denote analyticity

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Gamelin, Theodore W. (2004). Complex Analysis. Springer. ISBN 9788181281142.

- ^ Strichartz, Robert S. (1994). A guide to distribution theory and Fourier transforms. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8273-4. OCLC 28890674.

- ^ Krantz & Parks 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Komatsu, Hikosaburo (1960). "A characterization of real analytic functions". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. 36 (3): 90–93. doi:10.3792/pja/1195524081. ISSN 0021-4280.

- ^ "Gevrey class - Encyclopedia of Mathematics". encyclopediaofmath.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ^ Krantz & Parks 2002.

References

[edit]- Conway, John B. (1978). Functions of One Complex Variable I. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 11 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90328-6.

- Krantz, Steven; Parks, Harold R. (2002). A Primer of Real Analytic Functions (2nd ed.). Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-4264-1.

- Gamelin, Theodore W. (2004). Complex Analysis. Springer. ISBN 9788181281142.