Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

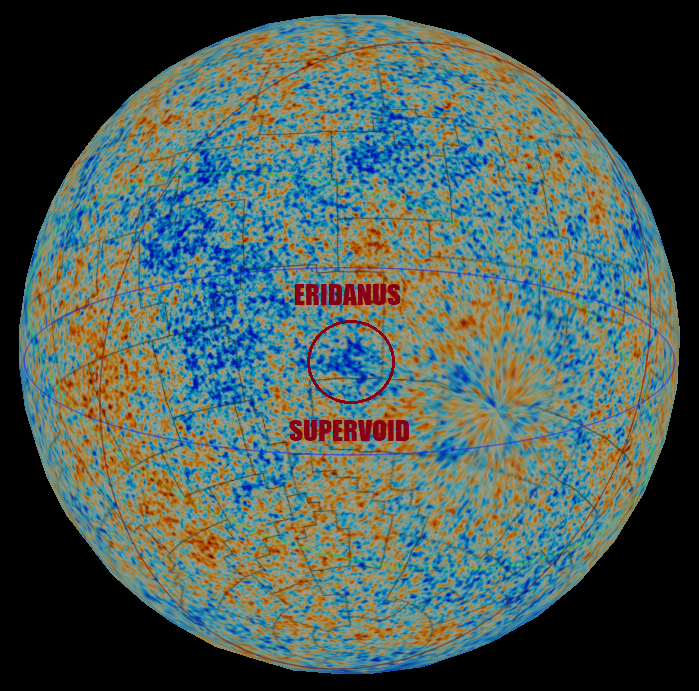

CMB cold spot

View on Wikipedia

The CMB Cold Spot or WMAP Cold Spot is a region of the sky seen in microwaves that has been found to be unusually large and cold relative to the expected properties of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR). The "Cold Spot" is approximately 70 μK (0.00007 K) colder than the average CMB temperature (approximately 2.7 K), whereas the root mean square of typical temperature variations is only 18 μK.[1][note 1] At some points, the "cold spot" is 140 μK colder than the average CMB temperature.[2]

The radius of the "cold spot" subtends about 5°; it is centered at the galactic coordinate lII = 207.8°, bII = −56.3° (equatorial: α = 03h 15m 05s, δ = −19° 35′ 02″). It is, therefore, in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere, in the direction of the constellation Eridanus.

Typically, the largest fluctuations of the primordial CMB temperature occur on angular scales of about 1°. Thus a cold region as large as the "cold spot" appears very unlikely, given generally accepted theoretical models. Various alternative explanations exist, including a so-called Eridanus Supervoid or Great Void that may exist between us and the primordial CMB (foreground voids can cause cold spots against the CMB). Such a void would affect the observed CMB via the integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect, and would be one of the largest structures in the observable universe. This would be an extremely large region of the universe, roughly 150 to 300 Mpc or 500 million to one billion light-years across and 6 to 10 billion light years away,[3] at redshift , containing a density of matter much smaller than the average density at that redshift.[citation needed]

Discovery and significance

[edit]

In the first year of data recorded by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), a region of sky in the constellation Eridanus was found to be colder than the surrounding area.[4] Subsequently, using the data gathered by WMAP over 3 years, the statistical significance of such a large, cold region was estimated. The probability of finding a deviation at least as high in Gaussian simulations was found to be 1.85%.[5] Thus it appears unlikely, but not impossible, that the cold spot was generated by the standard mechanism of quantum fluctuations during cosmological inflation, which in most inflationary models gives rise to Gaussian statistics. The cold spot may also, as suggested in the references above, be a signal of non-Gaussian primordial fluctuations.

Some authors called into question the statistical significance of this cold spot.[6]

In 2013, the CMB Cold Spot was also observed by the Planck satellite[7] at similar significance, discarding the possibility of being caused by a systematic error of the WMAP satellite.

Possible causes other than primordial temperature fluctuation

[edit]The large 'cold spot' forms part of what has been called an 'axis of evil' (so-called because it was unexpected to see a structure like this).[8]

Supervoid

[edit]

One possible explanation of the cold spot is a huge void between us and the primordial CMB. A region cooler than surrounding sightlines can be observed if a large void is present, as such a void would cause an increased cancellation between the "late-time" integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect and the "ordinary" Sachs–Wolfe effect.[10] This effect would be much smaller if dark energy were not stretching the void as photons went through it.[11]

Rudnick et al.[12] found a dip in NVSS galaxy number counts in the direction of the Cold Spot, suggesting the presence of a large void. Since then, some additional works have cast doubt on the "supervoid" explanation. The correlation between the NVSS dip and the Cold Spot was found to be marginal using a more conservative statistical analysis.[13] Also, a direct survey for galaxies in several one-degree-square fields within the Cold Spot found no evidence for a supervoid.[14] However, the supervoid explanation has not been ruled out entirely; it remains intriguing, since supervoids do seem capable of affecting the CMB measurably.[9][15][16]

A 2015 study shows the presence of a supervoid that has a diameter of 1.8 billion light years and is centered at 3 billion light-years from our galaxy in the direction of the Cold Spot, likely being associated with it.[11] This would make it the largest void detected, and one of the largest structures known.[17][note 2] Later measurements of the Sachs–Wolfe effect show too its likely existence.[18]

Although large voids are known in the universe, a void would have to be exceptionally vast to explain the cold spot, perhaps 1,000 times larger in volume than expected typical voids. It would be 6 billion–10 billion light-years away and nearly one billion light-years across, and would be perhaps even more improbable to occur in the large-scale structure than the WMAP cold spot would be in the primordial CMB.

A 2017 study[19] reported surveys showing no evidence that associated voids in the line of sight could have caused the CMB Cold Spot and concluded that it may instead have a primordial origin.

One important thing to confirm or rule out the late time integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect is the mass profile of galaxies in the area as ISW effect is affected by the galaxy bias which depends on the mass profiles and types of galaxies.[20][21]

In December 2021, the Dark Energy Survey (DES), analyzing their data, put forward more evidence for the correlation between the Eridanus supervoid and the CMB cold spot.[22][23]

Topological defects

[edit]In late 2007, (Cruz et al.)[24] argued that the Cold Spot could be due to a cosmic texture, a remnant of a phase transition in the early Universe. Other explanations based on cosmic defects have been proposed, such as the thawing of a cosmic string loop[25].

Parallel universe

[edit]A controversial claim by Laura Mersini-Houghton is that the cold spot could be the imprint of another universe beyond our own, caused by quantum entanglement between universes before they were separated by cosmic inflation.[3] Other researchers have modeled the cold spot as potentially the result of cosmological bubble collisions, again before inflation.[26][27][19]

A sophisticated computational analysis (using Kolmogorov complexity) has derived evidence for a north and a south cold spot in the satellite data:[28] "...among the high randomness regions is the southern non-Gaussian anomaly, the Cold Spot, with a stratification expected for the voids. Existence of its counterpart, a Northern Cold Spot with almost identical randomness properties among other low-temperature regions is revealed." However, apart from the Southern Cold Spot, the varied statistical methods in general fail to confirm each other regarding a Northern Cold Spot.[29] The 'K-map' used to detect the Northern Cold Spot was noted to have twice the measure of randomness measured in the standard model. The difference is speculated to be caused by the randomness introduced by voids (unaccounted-for voids were speculated to be the reason for the increased randomness above the standard model).[30]

Sensitivity to finding method

[edit]The cold spot is mainly anomalous because it stands out compared to the relatively hot ring around it; it is not unusual if one only considers the size and coldness of the spot itself.[6] More technically, its detection and significance depends on using a compensated filter like a Mexican hat wavelet to find it.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ After the dipole anisotropy, which is due to the Doppler shift of the microwave background radiation due to our peculiar velocity relative to the comoving cosmic rest frame, has been subtracted out. This feature is consistent with the Earth moving at some 627 km/s towards the constellation Virgo.

- ^ A claim by Szapudi et al states that the newly found void is the "largest structure ever identified by humanity". However, another source reports that the largest structure is the supercluster corresponding to the NQ2-NQ4 GRB overdensity at 10 billion light years.

References

[edit]- ^ Wright, E.L. (2004). "Theoretical Overview of Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy". In W. L. Freedman (ed.). Measuring and Modeling the Universe. Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. arXiv:astro-ph/0305591. Bibcode:2004mmu..symp..291W. ISBN 978-0-521-75576-4.

- ^ Woo, Marcus. "The largest thing in the universe". BBC. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b Chown, Marcus (2007). "The void: Imprint of another universe?". New Scientist. 196 (2631): 34–37. doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(07)62977-7.

- ^ Cruz, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, E.; Vielva, P.; Cayon, L. (2005). "Detection of a non-Gaussian Spot in WMAP". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 356 (1): 29–40. arXiv:astro-ph/0405341. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.356...29C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08419.x.

- ^ Cruz, M.; Cayon, L.; Martinez-Gonzalez, E.; Vielva, P.; Jin, J. (2007). "The non-Gaussian Cold Spot in the 3-year WMAP data". The Astrophysical Journal. 655 (1): 11–20. arXiv:astro-ph/0603859. Bibcode:2007ApJ...655...11C. doi:10.1086/509703. S2CID 121935762.

- ^ a b Zhang, Ray; Huterer, Dragan (2010). "Disks in the sky: A reassessment of the WMAP "cold spot"". Astroparticle Physics. 33 (2): 69. arXiv:0908.3988. Bibcode:2010APh....33...69Z. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.249.6944. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2009.11.005. S2CID 5552896.

- ^ Ade, P. A. R.; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (2013). "Planck 2013 results. XXIII. Isotropy and statistics of the CMB". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 571: A23. arXiv:1303.5083. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A..23P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321534. S2CID 13037411.

- ^ Milligan on March 22, 2006 10:31 PM. "WMAP: The Cosmic Axis of Evil – EGAD". Blog.lib.umn.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-06-07. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Granett, Benjamin R.; Neyrinck, Mark C.; Szapudi, István (2008). "An Imprint of Super-Structures on the Microwave Background due to the Integrated Sachs–Wolfe Effect". The Astrophysical Journal. 683 (2): L99 – L102. arXiv:0805.3695. Bibcode:2008ApJ...683L..99G. doi:10.1086/591670. S2CID 15976818.

- ^ Kaiki Taro Inoue; Silk, Joseph (2006). "Local Voids as the Origin of Large-angle Cosmic Microwave Background Anomalies I". The Astrophysical Journal. 648 (1): 23–30. arXiv:astro-ph/0602478. Bibcode:2006ApJ...648...23I. doi:10.1086/505636. S2CID 119080005.

- ^ a b Szapudi, I.; et al. (2015). "Detection of a supervoid aligned with the cold spot of the cosmic microwave background". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 450 (1): 288–294. arXiv:1405.1566. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.450..288S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv488.

- "Cold cosmic mystery solved: Largest known structure in the universe leaves its imprint on CMB radiation". Phys.org. April 20, 2015.

- ^ Rudnick, Lawrence; Brown, Shea; Williams, Liliya R. (2007). "Extragalactic Radio Sources and the WMAP Cold Spot". The Astrophysical Journal. 671 (1): 40–44. arXiv:0704.0908. Bibcode:2007ApJ...671...40R. doi:10.1086/522222. S2CID 14316362.

- ^ Smith, Kendrick M.; Huterer, Dragan (2010). "No evidence for the cold spot in the NVSS radio survey". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 403 (2): 2. arXiv:0805.2751. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.403....2S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15732.x. S2CID 16043676.

- ^ Granett, Benjamin R.; Szapudi, István; Neyrinck, Mark C. (2010). "Galaxy Counts on the CMB Cold Spot". The Astrophysical Journal. 714 (825): 825–833. arXiv:0911.2223. Bibcode:2010ApJ...714..825G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/714/1/825. S2CID 118614796.

- ^ Dark Energy and the Imprint of Super-Structures on the Microwave Background

- ^ Finelli, Fabio; Garcia-Bellido, Juan; Kovacs, Andras; Paci, Francesco; Szapudi, Istvan (2014). "A Supervoid Imprinting the Cold Spot in the Cosmic Microwave Background". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 455 (2): 1246. arXiv:1405.1555. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.455.1246F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2388.

- ^ "Mysterious 'Cold Spot': Fingerprint of Largest Structure in the Universe?". Discovery News. 2017-05-10. Archived from the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- ^ Seshadri, Nadatur; Crittenden, Robert (2016). "A detection of the integrated Sachs-Wolfe imprint of cosmic superstructures using a matched-filter approach". The Astrophysical Journal. 830 (2016): L19. arXiv:1608.08638. Bibcode:2016ApJ...830L..19N. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/830/1/L19. S2CID 55896975.

- ^ a b Mackenzie, Ruari; et al. (2017). "Evidence against a supervoid causing the CMB Cold Spot". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 470 (2): 2328–2338. arXiv:1704.03814. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.470.2328M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx931.

Another explanation could be that the Cold Spot is the remnant of a collision between our Universe and another 'bubble' universe during an early inflationary phase (Chang et al. 2009, Larjo & Levi 2010).

- ^ Rahman, Syed Faisal ur (2020). "The enduring enigma of the cosmic cold spot". Physics World. 33 (2): 36. Bibcode:2020PhyW...33b..36R. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/33/2/35. S2CID 216440967.

- ^ Dupe, F.X. (2011). "Measuring the integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 534: A51. arXiv:1010.2192. Bibcode:2011A&A...534A..51D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015893. S2CID 14737577.

- ^ Kovács, A; Jeffrey, N; Gatti, M; Chang, C; Whiteway, L; Hamaus, N; Lahav, O; Pollina, G; Bacon, D; Kacprzak, T; Mawdsley, B (2021-12-17). "The DES view of the Eridanus supervoid and the CMB cold spot". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 510 (1): 216–229. arXiv:2112.07699. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab3309. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ "Our Universe is normal! Its biggest anomaly, the CMB cold spot, is now explained". Big Think. February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Cruz, M.; N. Turok; P. Vielva; E. Martínez-González; M. Hobson (2007). "A Cosmic Microwave Background Feature Consistent with a Cosmic Texture". Science. 318 (5856): 1612–4. arXiv:0710.5737. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1612C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.246.8138. doi:10.1126/science.1148694. PMID 17962521. S2CID 12735226.

- ^ Ringeval, C.; D. Yamauchi; J. Yokoyama; F.R. Bouchet (2016). "Large scale CMB anomalies from thawing cosmic strings". JCAP. 02 (2016): 033. arXiv:1510.01916. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2016/02/033.

- ^ Chang, Spencer; Kleban, Matthew; Levi, Thomas S. (2009). "Watching Worlds Collide: Effects on the CMB from Cosmological Bubble Collisions". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2009 (4): 025. arXiv:0810.5128. Bibcode:2009JCAP...04..025C. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2009/04/025. S2CID 15683857.

- ^ Czech, Bartłomiej; Kleban, Matthew; Larjo, Klaus; Levi, Thomas S; Sigurdson, Kris (2010). "Polarizing bubble collisions". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2010 (12): 023. arXiv:1006.0832. Bibcode:2010JCAP...12..023C. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2010/12/023. S2CID 250776263.

- ^ Gurzadyan, V. G.; et al. (2009). "Kolmogorov cosmic microwave background sky". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 497 (2): 343. arXiv:0811.2732. Bibcode:2009A&A...497..343G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911625. S2CID 16262725.

- ^ Rossmanith, G.; Raeth, C.; Banday, A. J.; Morfill, G. (2009). "Non-Gaussian Signatures in the five-year WMAP data as identified with isotropic scaling indices". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 399 (4): 1921–1933. arXiv:0905.2854. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399.1921R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15421.x. S2CID 11586058.

- ^ Gurzadyan, V. G.; Kocharyan, A. A. (2008). "Kolmogorov stochasticity parameter measuring the randomness in Cosmic Microwave Background". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 492 (2): L33. arXiv:0810.3289. Bibcode:2008A&A...492L..33G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200811188.