Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Compton scattering

View on Wikipedia

| Light–matter interaction |

|---|

|

| Low-energy phenomena: |

| Photoelectric effect |

| Mid-energy phenomena: |

| Thomson scattering |

| Compton scattering |

| High-energy phenomena: |

| Pair production |

| Photodisintegration |

| Photofission |

Compton scattering (or the Compton effect) is the quantum theory of scattering of a high-frequency photon through an interaction with a charged particle, usually an electron. Specifically, when the photon interacts with a loosely bound electron, it releases the electron from an outer valence shell of an atom or molecule.

The effect was discovered in 1923 by Arthur Holly Compton while researching the scattering of X-rays by light elements, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927. The Compton effect significantly deviated from dominating classical theories, using both special relativity and quantum mechanics to explain the interaction between high frequency photons and charged particles.

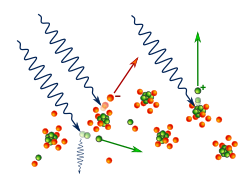

Photons can interact with matter at the atomic level (e.g. photoelectric effect and Rayleigh scattering), at the nucleus, or with only an electron. Pair production and the Compton effect occur at the level of the electron.[1] When a high-frequency photon scatters due to an interaction with a charged particle, the photon's energy is reduced, and thus its wavelength is increased. This trade-off between wavelength and energy in response to the collision is the Compton effect. Because of conservation of energy, the energy that is lost by the photon is transferred to the recoiling particle (such an electron would be called a "Compton recoil electron").

This implies that if the recoiling particle initially carried more energy than the photon has, the reverse would occur. This is known as inverse Compton scattering, in which the scattered photon increases in energy.

Introduction

[edit]

In Compton's original experiment (see Fig. 1), the energy of the X-ray photon (≈ 17 keV) was significantly larger than the binding energy of the atomic electron, so the electrons could be treated as being free after scattering. The amount by which the light's wavelength changes is called the Compton shift. Although Compton scattering from a nucleus exists,[3] Compton scattering usually refers to the interaction involving only the electrons of an atom. The Compton effect was observed by Arthur Holly Compton in 1923 at Washington University in St. Louis and further verified by his graduate student Y. H. Woo in the years following. Compton was awarded the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery.

The effect is significant because it demonstrates that light cannot be explained purely as a wave phenomenon.[4] Thomson scattering, the classical theory of an electromagnetic wave scattered by charged particles, cannot explain shifts in wavelength at low intensity: classically, light of sufficient intensity for the electric field to accelerate a charged particle to a relativistic speed will cause radiation-pressure recoil and an associated Doppler shift of the scattered light,[5] but the effect would become arbitrarily small at sufficiently low light intensities regardless of wavelength. Thus, if we are to explain low-intensity Compton scattering, light must behave as if it consists of particles. Or the assumption that the electron can be treated as free is invalid resulting in the effectively infinite electron mass equal to the nuclear mass (see e.g. the comment below on elastic scattering of X-rays being from that effect). Compton's experiment convinced physicists that light can be treated as a stream of particle-like objects (quanta called photons), whose energy is proportional to the light wave's frequency.

As shown in Fig. 2, the interaction between an electron and a photon results in the electron being given part of the energy (making it recoil), and a photon of the remaining energy being emitted in a different direction from the original, so that the overall momentum of the system is also conserved. If the scattered photon still has enough energy, the process may be repeated. In this scenario, the electron is treated as free or loosely bound. Experimental verification of momentum conservation in individual Compton scattering processes by Bothe and Geiger as well as by Compton and Simon has been important in disproving the BKS theory.

Compton scattering is commonly described as inelastic scattering. This is because, unlike the more common Thomson scattering that happens at the low-energy limit, the energy in the scattered photon in Compton scattering is less than the energy of the incident photon.[6][7] As the electron is typically weakly bound to the atom, the scattering can be viewed from either the perspective of an electron in a potential well, or as an atom with a small ionization energy. In the former perspective, energy of the incident photon is transferred to the recoil particle, but only as kinetic energy. The electron gains no internal energy, respective masses remain the same, the mark of an elastic collision. From this perspective, Compton scattering could be considered elastic because the internal state of the electron does not change during the scattering process. In the latter perspective, the atom's state is changed, constituting an inelastic collision. Whether Compton scattering is considered elastic or inelastic depends on which perspective is being used, as well as the context.

Compton scattering is one of four competing processes when photons interact with matter. At energies of a few eV to a few keV, corresponding to visible light through soft X-rays, a photon can be completely absorbed and its energy can eject an electron from its host atom, a process known as the photoelectric effect. High-energy photons of 1.022 MeV and above may bombard the nucleus and cause an electron and a positron to be formed, a process called pair production; even-higher-energy photons (beyond a threshold energy of at least 1.670 MeV, depending on the nuclei involved), can eject a nucleon or alpha particle from the nucleus in a process called photodisintegration. Compton scattering is the most important interaction in the intervening energy region, at photon energies greater than those typical of the photoelectric effect but less than the pair-production threshold.

Description of the phenomenon

[edit]

By the early 20th century, research into the interaction of X-rays with matter was well under way. It was observed that when X-rays of a known wavelength interact with atoms, the X-rays are scattered through an angle and emerge at a different wavelength related to . Although classical electromagnetism predicted that the wavelength of scattered rays should be equal to the initial wavelength,[8] multiple experiments had found that the wavelength of the scattered rays was longer (corresponding to lower energy) than the initial wavelength.[8]

In 1923, Compton published a paper that explained the X-ray shift by attributing particle-like momentum to light quanta (Albert Einstein had proposed light quanta in 1905 in explaining the photo-electric effect, but Compton did not build on Einstein's work). The energy of light quanta depends only on the frequency of the light. In his paper, Compton derived the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays by assuming that each scattered X-ray photon interacted with only one electron. His paper concludes by reporting on experiments which verified his derived relation: where

- is the initial wavelength,

- is the wavelength after scattering,

- is the Planck constant,

- is the electron rest mass,

- is the speed of light, and

- is the scattering angle.

The quantity h/mec is known as the Compton wavelength of the electron; it is equal to 2.43×10−12 m. The wavelength shift λ′ − λ is at least zero (for θ = 0°) and at most twice the Compton wavelength of the electron (for θ = 180°).

Compton found that some X-rays experienced no wavelength shift despite being scattered through large angles; in each of these cases the photon failed to eject an electron.[8] Thus the magnitude of the shift is related not to the Compton wavelength of the electron, but to the Compton wavelength of the entire atom, which can be upwards of 10000 times smaller. This is known as "coherent" scattering off the entire atom since the atom remains intact, gaining no internal excitation.

In Compton's original experiments the wavelength shift given above was the directly measurable observable. In modern experiments it is conventional to measure the energies, not the wavelengths, of the scattered photons. For a given incident energy , the outgoing final-state photon energy, , is given by

Derivation of the scattering formula

[edit]| Feynman diagrams (time from left to right) |

|---|

s channel

|

u channel

|

A photon γ with wavelength λ collides with an electron e in an atom, which is treated as being at rest. The collision causes the electron to recoil, and a new photon γ′ with wavelength λ′ emerges at angle θ from the photon's incoming path. Let e′ denote the electron after the collision. Compton allowed for the possibility that the interaction would sometimes accelerate the electron to speeds sufficiently close to the velocity of light as to require the application of Einstein's special relativity theory to properly describe its energy and momentum.

At the conclusion of Compton's 1923 paper, he reported results of experiments confirming the predictions of his scattering formula, thus supporting the assumption that photons carry momentum as well as quantized energy. At the start of his derivation, he had postulated an expression for the momentum of a photon from equating Einstein's already established mass-energy relationship of E = mc2 to the quantized photon energies of hf, which Einstein had separately postulated. If mc2 = hf, the equivalent photon mass must be hf/c2. The photon's momentum is then simply this effective mass times the photon's frame-invariant velocity c. For a photon, its momentum , and thus hf can be substituted for pc for all photon momentum terms which arise in course of the derivation below. The derivation which appears in Compton's paper is more terse, but follows the same logic in the same sequence as the following derivation.

The conservation of energy E merely equates the sum of energies before and after scattering.

Compton postulated that photons carry momentum;[8] thus from the conservation of momentum, the momenta of the particles should be similarly related by

in which pe is omitted as being negligible.

The photon energies are related to the frequencies by

where h is the Planck constant.

Before the scattering event, the electron is treated as sufficiently close to being at rest that its total energy consists entirely of the mass–energy equivalence of its rest mass me,

After scattering, the possibility that the electron might be accelerated to a significant fraction of the speed of light, requires that its total energy be represented using the relativistic energy–momentum relation

Substituting these quantities into the expression for the conservation of energy gives

This expression can be used to find the magnitude of the momentum of the scattered electron,

| 1 |

Note that this magnitude of the momentum gained by the electron (formerly zero) exceeds the energy/c lost by the photon,

Equation (1) relates the various energies associated with the collision. The electron's momentum change involves a relativistic change in the energy of the electron, so it is not simply related to the change in energy occurring in classical physics. The change of the magnitude of the momentum of the photon is not just related to the change of its energy; it also involves a change in direction.

Solving the conservation of momentum expression for the scattered electron's momentum gives

Making use of the scalar product yields the square of its magnitude,

In anticipation of being replaced with hf, multiply both sides by c2,

After replacing the photon momentum terms with hf/c, we get a second expression for the magnitude of the momentum of the scattered electron,

| 2 |

Equating the alternate expressions for this momentum gives

which, after evaluating the square and canceling and rearranging terms, further yields

Dividing both sides by 2hff′mec yields

Finally, since fλ = f′λ′ = c,

| 3 |

It can further be seen that the angle φ of the outgoing electron with the direction of the incoming photon is specified by

| 4 |

Applications

[edit]Compton scattering

[edit]Compton scattering is of prime importance to radiobiology, as it is the most probable interaction of gamma rays and high energy X-rays with atoms in living beings and is applied in radiation therapy.[9] [10]

Compton scattering is an important effect in gamma spectroscopy which gives rise to the Compton edge, as it is possible for the gamma rays to scatter out of the detectors used. Compton suppression is used to detect stray scatter gamma rays to counteract this effect.

Magnetic Compton scattering

[edit]Magnetic Compton scattering is an extension of the previously mentioned technique which involves the magnetisation of a crystal sample hit with high energy, circularly polarised photons. By measuring the scattered photons' energy and reversing the magnetisation of the sample, two different Compton profiles are generated (one for spin up momenta and one for spin down momenta). Taking the difference between these two profiles gives the magnetic Compton profile (MCP), given by – a one-dimensional projection of the electron spin density. where is the number of spin-unpaired electrons in the system, and are the three-dimensional electron momentum distributions for the majority spin and minority spin electrons respectively.

Since this scattering process is incoherent (there is no phase relationship between the scattered photons), the MCP is representative of the bulk properties of the sample and is a probe of the ground state. This means that the MCP is ideal for comparison with theoretical techniques such as density functional theory. The area under the MCP is directly proportional to the spin moment of the system and so, when combined with total moment measurements methods (such as SQUID magnetometry), can be used to isolate both the spin and orbital contributions to the total moment of a system. The shape of the MCP also yields insight into the origin of the magnetism in the system.[11][12]

Inverse Compton scattering

[edit]Inverse Compton scattering is important in astrophysics. In X-ray astronomy, the accretion disk surrounding a black hole is presumed to produce a thermal spectrum. The lower energy photons produced from this spectrum are scattered to higher energies by relativistic electrons in the surrounding corona. This is surmised to cause the power law component in the X-ray spectra (0.2–10 keV) of accreting black holes.[13]

The effect is also observed when photons from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) move through the hot gas surrounding a galaxy cluster. The CMB photons are scattered to higher energies by the electrons in this gas, resulting in the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect. Observations of the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect provide a nearly redshift-independent means of detecting galaxy clusters.

Some synchrotron radiation facilities scatter laser light off the stored electron beam. This Compton backscattering produces high energy photons in the MeV to GeV range[14][15] subsequently used for nuclear physics experiments.

Non-linear inverse Compton scattering

[edit]Non-linear inverse Compton scattering (NICS) is the scattering of multiple low-energy photons, given by an intense electromagnetic field, in a high-energy photon (X-ray or gamma ray) during the interaction with a charged particle, such as an electron.[16] It is also called non-linear Compton scattering and multiphoton Compton scattering. It is the non-linear version of inverse Compton scattering in which the conditions for multiphoton absorption by the charged particle are reached due to a very intense electromagnetic field, for example the one produced by a laser.[17]

Non-linear inverse Compton scattering is an interesting phenomenon for all applications requiring high-energy photons since NICS is capable of producing photons with energy comparable to the charged particle rest energy and higher.[18] As a consequence NICS photons can be used to trigger other phenomena such as pair production, Compton scattering, nuclear reactions, and can be used to probe non-linear quantum effects and non-linear QED.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pattison, Philip (1975). "X-Ray and Gamma Ray Scattering" (PDF). Warwick Database. University of Warwick: 10 – via Warwick Library.

- ^ Seltzer, Stephen (2009-09-17). "XCOM: Photon Cross Sections Database". NIST. doi:10.18434/T48G6X.

- ^ P. Christillin (1986). "Nuclear Compton scattering". J. Phys. G: Nucl. Phys. 12 (9): 837–851. Bibcode:1986JPhG...12..837C. doi:10.1088/0305-4616/12/9/008. S2CID 250783416.

- ^ Griffiths, David (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. Wiley. pp. 15, 91. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- ^ C. Moore (1995). "Observation of the Transition from Thomson to Compton Scattering in Optical Multiphoton Interactions with Electrons" (PDF).

- ^ Carron, NJ (2007). An Introduction to the Passage of Energetic Particles through Matter. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4200-1237-8.

- ^ Chen, Sow-Hsin; Kotlarchyk, Michael (2007). Interactions of Photons and Neutrons with Matter (2nd ed.). Singapore: World Scientific. p. 271. ISBN 978-981-02-4214-5.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, J.R.; Zafiratos, C.D.; Dubson, M.A. (2004). Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 136–9. ISBN 0-13-805715-X.

- ^ Camphausen KA, Lawrence RC. "Principles of Radiation Therapy" Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- ^ Ridwan, S. M., El-Tayyeb, F., Hainfeld, J. F., & Smilowitz, H. M. (2020). Distributions of intravenous injected iodine nanoparticles in orthotopic U87 human glioma xenografts over time and tumor therapy. Nanomedicine, 15(24), 2369–2383. https://doi.org/10.2217/nnm-2020-0178

- ^ Malcolm Cooper (14 October 2004). X-Ray Compton Scattering. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-850168-8. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Barbiellini, B., Bansil, A. (2020). Scattering Techniques, Compton. Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90800-9.00107-4

- ^ Dr. Tortosa, Alessia. "Comptonization mechanisms in hot coronae in AGN. The NuSTAR view" (PDF). DIPARTIMENTO DI MATEMATICA E FISICA.

- ^ "GRAAL home page". Lnf.infn.it. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Duke University TUNL HIGS Facility". Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- ^ a b Di Piazza, A.; Müller, C.; Hatsagortsyan, K. Z.; Keitel, C. H. (2012-08-16). "Extremely high-intensity laser interactions with fundamental quantum systems". Reviews of Modern Physics. 84 (3): 1177–1228. arXiv:1111.3886. Bibcode:2012RvMP...84.1177D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1177. ISSN 0034-6861. S2CID 118536606.

- ^ Meyerhofer, D.D. (1997). "High-intensity-laser-electron scattering". IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics. 33 (11): 1935–1941. Bibcode:1997IJQE...33.1935M. doi:10.1109/3.641308.

- ^ Ritus, V. I. (1985). "Quantum effects of the interaction of elementary particles with an intense electromagnetic field". Journal of Soviet Laser Research. 6 (5): 497–617. doi:10.1007/BF01120220. ISSN 0270-2010. S2CID 121183948.

Further reading

[edit]- S. Chen; H. Avakian; V. Burkert; L. Vandenaweele; P. Eugenio; the CLAS collaboration; Ambrozewicz; Anghinolfi; Asryan; Bagdasaryan; Baillie; Ball; Baltzell; Barrow; Batourine; Battaglieri; Beard; Bedlinskiy; Bektasoglu; Bellis; Benmouna; Berman; Biselli; Bonner; Bouchigny; Boiarinov; Bosted; Bradford; Branford; et al. (2006). "Measurement of Deeply Virtual Compton Scattering with a Polarized Proton Target". Physical Review Letters. 97 (7) 072002. arXiv:hep-ex/0605012. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..97g2002C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.072002. PMID 17026221. S2CID 15326395.

- Compton, Arthur H. (May 1923). "A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-Rays by Light Elements". Physical Review. 21 (5): 483–502. Bibcode:1923PhRv...21..483C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.21.483. (the original 1923 paper on the APS website)

- Stuewer, Roger H. (1975), The Compton Effect: Turning Point in Physics (New York: Science History Publications)

External links

[edit]- Compton Scattering – Georgia State University

- Compton Scattering Data – Georgia State University

- Derivation of Compton shift equation