Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Canadian Corps

View on Wikipedia| Canadian Corps | |

|---|---|

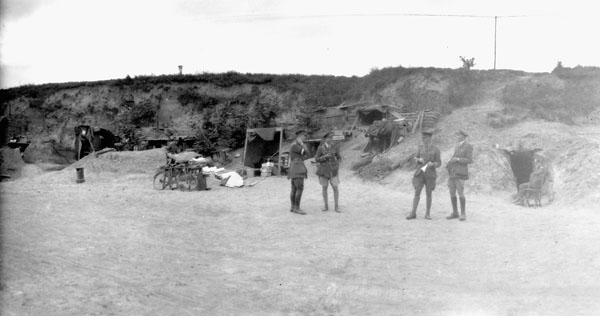

Canadian Corps Headquarters, Neuville-Vitasse, France, 1918 | |

| Active | 1915–1919 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Canadian Expeditionary Force |

| Size | 4 divisions |

| Part of | Various British field armies |

| Commanders | |

| 1915–1916 | General Sir Edwin Alderson |

| 1916–1917 | General Sir Julian Byng |

| 1917–1919 | General Sir Arthur Currie |

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December 1915 and the 4th Canadian Division in August 1916. The organization of a 5th Canadian Division began in February 1917 but it was still not fully formed when it was broken up in February 1918 and its men used to reinforce the other four divisions.

The majority of soldiers of the Canadian Corps were British-born Canadians until near the end of the war, when the number of those of Canadian birth who had enlisted rose to 51 percent.[1] They were mostly volunteers, as conscription was not implemented until the end of the war (see Conscription Crisis of 1917). Ultimately, only 24,132 conscripts made it to France before 11 November 1918. In the later stages of the war the Canadian Corps was regarded by friend and foe alike as one of the most effective Allied military formations on the Western Front.[2]

History

[edit]

Although the corps was within and under the command of the British Expeditionary Force, understandably there was considerable political pressure in Canada, especially following the Battle of the Somme, in 1916, to have the corps fight as a single unit rather than have the divisions dissipated through the whole army.[3] The corps was commanded by Lieutenant General Sir E.A.H. Alderson, until 1916. Political considerations[4] caused command to be passed to Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng. When Byng was promoted to a higher command during the summer of 1917, he was succeeded by General Sir Arthur Currie, the commander of the 1st Division, giving the corps its first Canadian commander. Currie was able to reconcile the desire for national independence with the need for Allied integration. He resisted pressure to replace all British officers in high-ranking positions, retaining those who were successful until they could be replaced by trained and experienced Canadians.[3] British staff officers made up a considerable part of the Corps – although by 1917, 7 of 12 infantry brigades were commanded by Canadians trained during the war, British regulars were the staff officers of the divisions and British officers held two-thirds of senior appointments across the infantry, artillery and Corps headquarters with only four of the most senior appointments being Canadian. Among the British officers were Alan Brooke (at the time a major of the Royal Artillery who planned the artillery barrages for Vimy Ridge and later) and William Ironside. Both eventually became Field Marshals and held the position of Chief of the Imperial General Staff.[5]

The Canadian Corps captured Vimy Ridge in April, 1917, in a daring attack that was a turning point in the war, and as Currie called it, "the grandest day the Corps ever had".[6] During the German spring offensive of the spring and summer of 1918, the Canadian Corps supported British and French soldiers while they held the Germans back.[7] Between August 8 and 11, 1918, the corps spearheaded the offensive during the Battle of Amiens. Here a significant defeat was inflicted on the Germans, causing the German commander-in-chief, General Erich Ludendorff, to call August 8 "the black day of the German army." This battle marked the start of the period of the war the French later named "Canada's Hundred Days". After Amiens, the Canadian Corps continued to help lead the vanguard of an Allied push that ultimately ended on 11 November 1918 at Mons where the British Empire had first met in conflict with Imperial German forces in 1914.[8]

At the end of war the Canadian 1st and 2nd Divisions took part in the occupation of Germany and the corps was eventually demobilized in 1919.[9] Upon their return home the veterans were greeted by large and welcoming crowds all across the country.[8] Total fatal battle casualties during the war was 56,638, 13.5% of the 418,052 sent overseas and 9.26% of the 611,711 who enlisted.[10]

Canadian Corps divisions

[edit]Battles

[edit]Following its formation in late 1915, the Canadian Corps readied to fight major battles as a unified entity, beginning in 1916. Additional actions were fought by one or more units of the corps (see separate listings for the divisions, above). Major battles fought by the corps were the following:

1916

[edit]- Battle of Mont Sorrel: June 2–13

- Battle of Flers–Courcelette: September 15–22

- Battle of Morval: September 25

- Battle of Thiepval Ridge: September 26–28

- Battle of Le Transloy: October 1–18

- Battle of the Ancre Heights: October 1 – November 11

1917

[edit]- Battle of Vimy Ridge: April 9–12

- Battle of Arras (1917): April 9 – May 16, 1917

- Battle of Arleux: April 28–29

- Third Battle of the Scarpe: May 3–4

- Battle of Hill 70: August 15–25

- Second Battle of Passchendaele: October 26 – November 10

1918

[edit]- Battle of Amiens: August 8–11

- Second Battle of the Somme: August 21 – September 2

- Battle of the Canal du Nord: September 27 – October 1 (including the capture of Bourlon Wood)

- Battle of Cambrai: October 8–9 (including the Capture of Cambrai)

Assessment

[edit]The military effectiveness of the corps has been extensively analyzed. The corps evolved steadily following the 1915 summer campaign. As Godefroy (2006) notes, the Canadian Expeditionary Force "worked ceaselessly to convert all of its available political and physical resources into fighting power."[2] One striking feature of the corps' evolution was its unique commitment and ability to exploit all opportunities for learning. This was a corps-wide activity, involving all levels from the commander to the private soldier. This ability to learn from allied successes and mistakes made the corps increasingly successful. Doctrine was tested in limited engagements and, if proven effectual, developed for larger scale battles. Following each engagement, lessons were recorded, analyzed and disseminated to all units. Doctrine and tactics that were ineffective or cost too many lives were discarded and new methods developed. This learning process, combined with technical innovation and competent senior leadership in theatre created one of the most effective allied fighting forces on the Western Front.[2]

Ruthlessness and Prisoner Treatment

[edit]This adaptive approach also shaped the Corps' reputation for ruthlessness, particularly in trench raids and the treatment of surrendering enemies, which enhanced its fearsome image among German forces.[12][13] German commanders reportedly reinforced sectors when facing Canadians, viewing them as "shock troops" prone to minimal quarter.[13][14] This reputation stemmed from aggressive tactics, the Corps' volunteer-heavy composition, and the brutalizing conditions of trench warfare, where similar acts occurred across all armies.[12][15]

Trench Raids and Deceptive Tactics

[edit]The Corps pioneered large-scale trench raids for intelligence and morale disruption, often resulting in no-quarter combat due to the risks of escorting prisoners during withdrawals.[16] A notable incident near Ypres (1916–1917), recounted in A Canadian Who Went, involved tossing corned beef tins to lure starving Germans before attacking with grenades and rifles, described as "gifts from hell".[17] Similar deceptions, such as exploiting Christmas truces, reinforced this image, as in the 1915 incident where Canadians responded to German greetings with machine-gun fire.[15]

Killing of Surrendering Prisoners

[edit]Executions of surrendering Germans were widespread, driven by revenge, safety concerns, and battlefield chaos.[12][18] Historian Tim Cook documented cases like Lieutenant R. C. Germain's bayoneting of prisoners ("a foot of cold steel thro them") and reprisals fueled by the debunked "Crucified Canadian" rumor of 1915.[12] While 42,000 Germans were captured overall, such killings were common in the fraught "politics of surrender".[12][15]

Context and Legacy

[edit]Motivations included fear of prisoners alerting enemies and revenge for alleged atrocities; though not unique, these acts amplified the Corps' reputation.[18] Postwar, they contributed to veterans' trauma, with historians like Cook urging a re-examination of sanitized narratives.[15]

In literature

[edit]Bartholomew Bandy, hero of The Bandy Papers series of humorous novels by Donald Jack, initially served as an infantry officer in the Canadian Corps before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps.

A large part of Robertson Davies' 1970 novel Fifth Business is devoted to the protagonist's experiences as a soldier in the Canadian Corps.

Lucy Maud Montgomery’s novel Rilla of Ingleside, (the 8th book in the “Anne of Green Gables” series), is one of the first successful commercial publications focusing on Canadian civilian and soldier World War I experiences. It is the only Canadian novel written of the First World War by a contemporary. It is also one of the first texts to mention the Gallipoli campaign as well as the ANZACs.

References

[edit]- ^ English, J. (1991). The Canadian Army and the Normandy Campaign: A Study of Failure in High Command. Praeger Publishers, p 15. ISBN 978-0-275-93019-6

- ^ a b c Godefroy, A. (April 1, 2006). "Canadian Military Effectiveness in the First World War." In The Canadian Way of War: Serving the National Interest Bernd Horn (ed.) Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-612-2

- ^ a b Weir, E. "Using the Legacy of World War I to Evaluate Canadian Military Leadership in World War II." Journal of Military and Strategic Studies. Fall 2004, 7(1) 7. Retrieved on 2010-05-24.

- ^ notably pertaining to the Ross Rifle controversy

- ^ Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment edited by Geoff Hayes, p97-99

- ^ Berton, P. (1986). Vimy. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. p. 292. ISBN 0-7710-1339-6.

- ^ "Spring Offensive". Loyal Edmonton Regiment Museum. 2001. Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ a b "Canada's Hundred Days". Veterans Affairs Canada. 2004-07-29. Archived from the original on 2009-05-26. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Library and Archives Canada (2008-11-07). Armistice. Canada and the First World War. Retrieved on: 2010-05-24.

- ^ Statistics Canada (2009-08-07). Number of casualties in the First World War, 1914 to 1918, and the Second World War, 1939 to 1945. Source: Canada Yearbook, 1948. Retrieved on: 2010-05-24.

- ^ Nicholson, Gerald W. L. (1962). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Cook, Tim (2006). "The Politics of Surrender: Canadian Soldiers and the Killing of Prisoners in the Great War". The Journal of Military History. 70 (3): 637–665. doi:10.1353/jmh.2006.0207.

- ^ a b Graves, Robert (1929). Good-Bye to All That. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 204.

- ^ Nicholson, G.W.L. (1962). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1919. Ottawa: Queen's Printer. p. 547.

- ^ a b c d Cook, Tim (2008). Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1917–1918. Toronto: Viking Canada. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-670-06666-7.

- ^ Cook, Tim (2007). At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1914–1916. Toronto: Viking Canada. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-670-06734-3.

- ^ A Canadian Who Went. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart. 1917. pp. 78–81.

- ^ a b Vance, Jonathan (1997). Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning, and the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7748-0600-8.

Bibliography

[edit]- Berton, P. (1986). Vimy. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-1339-6.

- Nicholson, G.W.L. (1964). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919, Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, Queen's Printer.

Further reading

[edit]- Christie, N. (1999). For King & Empire, The Canadians at Amiens, August 1918, CEF Books.

- Christie, N. (1997). For King & Empire, The Canadians at Arras, August – September 1918, CEF Books.

- Christie, N. (1997). For King & Empire, The Canadians at Cambrai, September – October 1918, CEF Books.

- Dancocks, D. (1987). Spearhead to Victory – Canada and the Great War, Hurtig Publishers

- Granatstein, J. (2004). Canada's Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8696-9.

- Morton, D. and Granatstein, J. (1989). Marching to Armageddon, Lester & Orpen Dennys Publishers.

- Morton, D. (1993). When Your Number's Up, Random House of Canada.

- Schreiber, S. (2004). Shock Army of the British Empire – The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War, Vanwell Publishing Limited.

External links

[edit]- Canadian Great War Project

- The C.E.F. Paper Trail

- The C.E.F. Study Group

- Library & Archives Canada Canada and the First World War Archived 2016-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Veteran Affairs Canada – History of the First World War

- CdnMilitary.ca Article on the CEF World War One Mobilization Problems

- Battle of Vimy Ridge Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine