Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

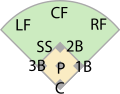

Center fielder

View on Wikipedia

A center fielder, abbreviated CF, is the outfielder in baseball who plays defense in center field – the baseball and softball fielding position between left field and right field. In the numbering system used to record defensive plays, the center fielder is assigned the number 8.[1]

Position description

[edit]Outfielders must cover large distances, so speed, instincts and quickness to react to the ball are key. They must be able to catch fly balls above their heads and on the run. They must be able to throw the ball accurately over a long distance to be effective.

As well as the requirements above, the center fielder must be the outfielder who has the best combination of speed and throwing distance. The center fielder "covers more 'grass' than any other player" (see photo) and, most likely, will catch the most fly balls. The position also has the greatest responsibility among the three outfielders for coordinating their play to prevent collisions when converging on a fly ball, and on plays where the center fielder does not make the catch, he must position himself behind the corner outfielder as backup. The center outfielder is the captain of the outfield and has the authority to call off the corner fielders when he has a better chance to catch the ball. Aside from requiring more speed and range, the center field position is slightly easier to field because balls tend to fly on a straight path, rather than curving as they do for the other outfield positions. A center fielder's vision and depth perception is a coveted skill and must be above average. Because the position requires a good arm and fast legs, center field is generally where the team puts its best all-around athletes; as a result, center fielders are often fine hitters as well. Many center fielders are renowned as excellent batters and base runners.

When a base runner is trying to steal second base the center fielder must back up second base on throws from the catcher to second base in case the second baseman misses the catch or it is a bad throw.

Hall of Fame center fielders

[edit]- Richie Ashburn

- Earl Averill

- Cool Papa Bell

- Willard Brown

- Max Carey

- Oscar Charleston

- Ty Cobb

- Earle Combs

- Joe DiMaggio

- Larry Doby

- Hugh Duffy

- Ken Griffey Jr.

- Billy Hamilton

- Pete Hill

- Mickey Mantle

- Willie Mays

- Kirby Puckett

- Edd Roush

- Duke Snider

- Tris Speaker

- Turkey Stearnes

- Cristóbal Torriente

- Lloyd Waner

- Zack Wheat

- Hack Wilson

- Robin Yount (played over half his games at shortstop)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nelson, Steve (December 4, 2020). "Understanding Every Baseball Position and Their Role". BaseballTrainingWorld.com.