Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Weiyang Palace

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Weiyang Palace | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

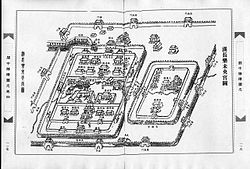

Visual recreation of Weiyang Palace. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 未央宮 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | The Endless Palace | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

The Weiyang Palace (Chinese: 未央宮) was the main imperial palace complex of the Han dynasty and numerous other Chinese dynasties, located in the city of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an). It was built in 200 BC at the request of the Emperor Gaozu of Han, under the supervision of his prime minister Xiao He. It served as the administrative centre and imperial residence of the Western Han, the Xin dynasty, the Eastern Han (during the reign of the Emperor Xian of Han), the Western Jin (during the reign of the Emperor Min of Jin), the Han-Zhao, the Former Qin, the Later Qin, the Western Wei, the Northern Zhou, and the early Sui dynasty.

The palace survived until the Tang dynasty when it was burned down by marauding invaders en route to the Tang capital Chang'an. This was the largest palace ever built on Earth,[1] covering 4.8 km2 (1,200 acres), which is 6.7 times the size of the current Forbidden City, or 11 times the size of the Vatican City.[2] Today, little remains of the former palace. The site of the palace, along with many other sites along the eastern section of the Silk Road, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014.

Name

[edit]"Weiyang" (未央) literally means "(something) hasn't reached its midpoint", "has more than a half to go", but colloquially it can be translated as "endless", which is probably what the name is actually alluding to. Together with the name of Changle Palace (長樂宮, perpetual happiness), which was built 2 years before, it can be interpreted to mean, "The perpetual happiness hasn't reached its midpoint yet."

Description

[edit]Weiyang palace was sited to the southwest of Han dynasty Chang'an and is therefore also called the Western Palace (西宫). Surrounded by walls, the palace complex was rectangular, with a length of 2,150 metres east–west and 2,250 metres north–south. Each side of the walls had a single main gate, with the eastern and northern gates (facing Chang'an city) built with gate towers.

Major architectures within the palace include:

- Front Hall (前殿)

- Xuanshi Hall (宣室殿)

- Wenshi Hall (温室殿)

- Qingliang Hall (清凉殿)

- Jinhua Hall (金华殿)

- Chengming Hall (承明殿)

- Gaomen Hall (高门殿)

- Baihu Hall (白虎殿)

- Yutang Hall (玉堂殿)

- Xuande Hall (宣德殿)

- Jiaofang Hall (椒房殿)

- Zhaoyang Hall (昭阳殿)

- Bailiang Platform (柏梁台)

- Qilin Pavilion (麒麟阁)

- Tianlu Pavilion (天禄阁)

- Shiqu Pavilion (石渠阁)

References

[edit]- ^ Spilsbury, Louise (2019). Ancient China. p. 20. ISBN 9781515725596.

- ^ "Weiyang Palace: the Largest Palace Ever Built on Earth". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-08-17.