Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chips Rafferty

View on Wikipedia

John William Pilbean Goffage MBE (26 March 1909 – 27 May 1971), known professionally as Chips Rafferty, was an Australian actor. Called "the living symbol of the typical Australian",[1] Rafferty's career stretched from the late 1930s until he died in 1971, and during this time he performed regularly in major Australian feature films such as Wake in Fright, as well as appearing in British and American productions, including The Overlanders and The Sundowners. He appeared in commercials in Britain during the late 1950s, encouraging British emigration to Australia.[2][3]

Key Information

Early days

[edit]John William Pilbean Goffage was born at Billy Goat Hill, near Broken Hill, New South Wales to John Goffage, an English-born stock agent, and Australian-born Violet Maude Joyce.[4][3] Gaining the nickname "Chips" as a school boy,[4] Rafferty studied at Parramatta Commercial School. At age 16, Rafferty began an apprenticeship as an iron moulder at Clyde Engineering Works[3] before working in a variety of jobs, including opal miner, sheep shearer, drover, RAAF officer[5][6] and pearl diver.[1][7]

Film career

[edit]Rafferty was in his thirties when he made his debut at Cinesound Studios.[3] His first film role was as a fireman in Ken G. Hall's comedy Dad Rudd, M.P. (1940)[8] - Hall later recalled he was looking for an actor who was tall and skinny as a visual contrast to others and Cinesound's casting director, Ron Whelan, introduced Hall to Rafferty. Hall enjoyed Rafferty's performance and when he shot some additional scenes for the comedy Ants in His Pants he used Rafferty again, although the part was much smaller.[9] (This film was released prior to Dad Rudd MP which is why many list it first on Rafferty's filmography.)[10] At that time, he managed a wine cellar in Bond Street, Sydney.[11]

Forty Thousand Horsemen

[edit]

Rafferty leapt to international fame when cast as one of the three leads in Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), a film directed by Charles Chauvel that focused on the Battle of Beersheba in 1917. Rafferty's part was originally given to Pat Hanna but Chauvel changed his mind after being introduced to Rafferty by Ron Whelen and seeing a screen test with Rafferty.[12][7] Chauvel described him as "a cross between Slim Summerville and James Stewart, and has a variety of droll yet natural humour."[13] According to Filmink "Rafferty’s inexperience is evident, but it’s made up for by his presence."[14]

Forty Thousand Horsemen was enormously popular and was screened throughout the world, becoming one of the most-seen Australian films made to that point. Although the film's romantic leads were Grant Taylor (actor) and Betty Bryant, Rafferty's performance received much acclaim.[15]

War service

[edit]Rafferty married (1) Jean Stewart Ferguson, daughter of John Ferguson of Belmore at St. Stephen's Presbyterian Church, Sydney on 16 November 1935, divorcing in 1940 in Sydney.

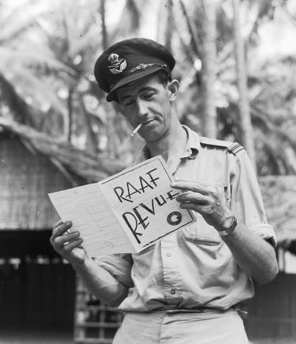

Rafferty married (2) Ellen Kathleen "Quentin" Jameson on 28 May 1941.[16] He enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force the next day[clarification needed] and entertained troops.[5]

During the war, Rafferty was allowed to make films on leave. He appeared in a short featurette, South West Pacific (1943), directed by Hall.[17] He was reunited with Chauvel and Grant Taylor in The Rats of Tobruk (1944), an attempt to repeat the success of Forty Thousand Horsemen.[18]

Rafferty was discharged on 13 February 1945, having reached the rank of Flying Officer.[19]

International fame

[edit]Ealing Studios were interested in making a feature film in Australia after the war, and assigned Harry Watt to find a subject. He came up with The Overlanders (1946), a story of a cattle drive during war time (based on a true story) and gave the lead role to Rafferty who Watt called an "Australian Gary Cooper."[20]

Rafferty's fee was £25 a week.[21] Ealing Studios were so pleased they signed Rafferty to a long-term contract even before the film was released. The film was a critical and commercial success and Rafferty was established as a film star.[citation needed]

Ealing Studios were associated with Rank Films, who cast Rafferty in the lead of Bush Christmas (1947), a children's movie where Rafferty played the villain. It was very popular.[citation needed]

Ealing Studios signed Rafferty to a long-term contract. He went to England to promote The Overlanders and Ealing put him in The Loves of Joanna Godden. While promoting the film in Hollywood he met Hedda Hopper who said Rafferty "created quite a stir. They call him the Australian Gary Cooper, but if he were cut down a bit he would be more like the late Will Rogers. I don't know how they'll get him on the screen unless they do it horizontally... He is as natural as an old shoe."[22]

Ealing and Watt wanted to make another film in Australia and decided on a spectacle, Eureka Stockade. Rafferty was cast in the lead as Peter Lalor, the head of the rebellion, despite pressures in some quarters to cast Peter Finch. The result was a box office disappointment and Rafferty's performance was much criticised.[23][24] A writer called it "one of the most spectacular pieces of miscasting in Australian cinematic history".[25]

Rafferty was meant to follow this with a comedy for Ealing co-starring Tommy Trinder. Instead, Ealing put the two actors in a drama about aboriginal land rights Bitter Springs (1950). The film was not widely popular and Ealing wound up their filmmaking operation in Australia.[23][26]

Rafferty kept busy as an actor, appearing on radio in a show Chips: Story of an Outback. He was cast by 20th Century Fox in a melodrama they shot in Australia, Kangaroo (1952). The studio liked his performance enough that they flew him (and Charles Tingwell) over to Los Angeles to play Australian soldiers in The Desert Rats (1953), a war movie.[27]

Producer

[edit]Film production in Australia had slowed to a trickle and Rafferty decided to move into movie production. He wanted to make The Green Opal, a story about immigration but could not get finance. However he then teamed up with a producer-director Lee Robinson and they decided to make movies together.[23][28]

Their first movie was The Phantom Stockman (1953), directed by Robinson and starring Rafferty, and produced by them both. The film was profitable.[29] It was followed by King of the Coral Sea, which was even more popular, and introduced Rod Taylor to cinema audiences.[30] Rafferty and Robinson attracted the interest of the French, collaborated with them on the New Guinea adventure tale, Walk Into Paradise (1956). This was their most popular movie to date.[31]

Rafferty also appeared as an actor only in a British-financed comedy set in Australia, Smiley (1956). It was successful and led to a sequel, Smiley Gets a Gun (1958), in which Rafferty reprised his role. In England he appeared in The Flaming Sword (1958).

He also participated in cinema advertisements that were part of an Australian Government campaign in 1957 called "Bring out a Briton". The campaign was launched in a bid to increase the number of British migrants settling in Australia.[citation needed]

Rafferty and Robinson raised money for three more movies with Robinson. He elected not to appear in the fourth film he produced with Robinson, Dust in the Sun (1958), their first flop together. Nor was he in The Stowaway (1959) and The Restless and the Damned (1960). All three films lost money and Rafferty found himself in financial difficulty.[32]

Later career

[edit]Rafferty returned to being an actor only. He had a small role in The Sundowners (1960), with Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr and played a coastwatcher in The Wackiest Ship in the Army (1960) with Jack Lemmon and Ricky Nelson. He guest starred in several episodes of the Australian-shot TV series Whiplash (1961).

Rafferty was cast as one of the mutineers in the 1962 remake of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Marlon Brando. The filming of Bounty in Tahiti dragged longer than six months but it restored him to financial health after the failure of his production company; it enabled him to buy a block of flats which supported him for the rest of his life.[33] Rafferty dubbed the film The Bounteous Mutiny.

In 1962, the 6 foot 5 inch actor was socialising with fellow expatriates in a London club when they were joined by an Australian who acted as doorman, and unbeknownst to Rafferty, was a professional wrestler. Claiming he was being ignored after helping them get in the doorman was so argumentative that Rafferty was provoked into accepting a challenge to 'step outside'. In the severe beating that followed he sustained deep grazing across his face and suffered a myocardial infarction (he had not been aware of having a heart condition until the incident) costing him the chance at roles in two major film productions.[34][35]

In 1963 he recorded a long play record with Festival Records (FL-31015) titled A Man and His Horse, narrating a selection of works from Australian verse composers including Banjo Paterson (1864–1941), Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833–1870) and Will H. Ogilvie (1869–1963).[36]

Rafferty appeared in some episodes of the series Adventure Unlimited shot in 1963.[37] He played the Australian Prime Minister in the Australian sci-fi TV series The Stranger (1964) then travelled to England and appeared in eight episodes of Emergency-Ward 10 (1964). While in England he was in The Winds of Green Monday (1965) on British TV.

He travelled to the US and guest starred in episodes of The Wackiest Ship in the Army (1965) (as a different character to the role that he played in the movie version). This led to further offers to work in Hollywood on television shows; he played a Union soldier in The Big Valley (1966) with a noticeably Australian accent. He was also in episodes of Gunsmoke (1966) and Daktari (1966). "What else can I do but look to America for my future when there is still no assistance or help from the government," said in April 1966.[38]

Back in Australia Rafferty had a good part in the Australian-shot comedy They're a Weird Mob (1966) a big local success.[39] He returned to Hollywood to appear in episodes of The Girl from UNCLE (1967), Tarzan (1967) and The Monkees, as well as the Elvis Presley movie Double Trouble (1967) and the adventure tale Kona Coast (1968)

Returning to Australia he guest-starred in Skippy the Bush Kangaroo, Adventures of the Seaspray (1967), Rita and Wally (1968), Woobinda, Animal Doctor (1970) and Dead Men Running (1971). He continued to make films such as Skullduggery (1970).

Rafferty's final film role was in 1971's Wake in Fright, where he played an outback policeman. (The movie was filmed mainly in and around Rafferty's home town of Broken Hill.) In a review of the film, a critic praised Rafferty's performance, writing that he "exudes an unnerving intensity with a deceptively menacing and disturbing performance that ranks among the best of his career".[40]

His final performance was in an episode of the Australian war series Spyforce (1971).

Hours before he died, Rafferty was offered a prominent role in a film The Day the Clown Cried by Jerry Lewis which was never completed or released.[1]

Death

[edit]On 27 May 1971, Rafferty collapsed and died of a heart attack at the age of 62, while walking down a Sydney street shortly after completing his role in Wake in Fright.[6][41] His wife Ellen had predeceased him in 1964 and they had no children.[16] His remains were cremated and his ashes scattered into his favourite fishing hole in Lovett Bay.

Rafferty had been married to Jean Stewart Ferguson from 1935 to 1940.[42]

Honours

[edit]In the 1971 New Years' Honours, Rafferty was made a Member of the Order of British Empire (MBE) by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to the performing arts.[43]

Australia Post issued a stamp in 1989 that depicted Rafferty in recognition of his work in Australian cinema, and in March 2006, Broken Hill City Council announced that the town's Entertainment Centre would be named in honour of Rafferty.[citation needed]

The Oxford Companion to Australian Film refers to Rafferty as "Australia's most prominent and significant actor of the 1940s–60s".[44]

Australian singer/songwriter Richard Davies wrote a song, "Chips Rafferty" for his album, There's Never Been A Crowd Like This.[citation needed]

Associations

[edit]He was also a talented artist, and as "Long John Goffage" was a leading light of the Black and White Artists' Club.[11] He was a Freemason.[45]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Come Up Smiling (aka Ants in His Pants) | Man in Crowd (uncredited) | Feature film |

| 1940 | Dad Rudd, MP | Fireman (uncredited) | Feature film |

| Forty Thousand Horsemen | Jim | Feature film | |

| 1943 | South West Pacific | RAAF Mechanic | Short film |

| 1944 | The Rats of Tobruk | Milo Trent | Feature film |

| 1946 | The Overlanders | Dan McAlpine | Feature film |

| 1947 | Bush Christmas | Long Bill | Feature film |

| The Loves of Joanna Godden | Collard | Feature film | |

| 1949 | Eureka Stockade (aka Massacre Hill) | Peter Lalor | Feature film |

| 1950 | Bitter Springs | Wally King | Feature film |

| 1952 | Kangaroo (aka The Australian Story) | Trooper 'Len' Leonard | Feature film |

| 1953 | The Desert Rats | Sergeant 'Blue' Smith | Feature film |

| The Phantom Stockman (aka Return of the Plainsman) | The Sundowner | Feature film. Also producer and co-writer. | |

| King of the Coral Sea | Ted King | Feature film. Also producer and co-writer. | |

| 1956 | Smiley | Sergeant Flaxman | Feature film |

| Walk Into Paradise (aka Walk into Hell) | Steve MacAllister | Feature film. Also producer. | |

| 1958 | Smiley Gets a Gun | Sergeant Flaxman | Feature film |

| The Flaming Sword | Long Tom | Feature film | |

| 1960 | The Sundowners | Quinlan | Feature film |

| The Wackiest Ship in the Army | Patterson | Feature film | |

| 1962 | Mutiny on the Bounty | Michael Byrne | Feature film. Feature film |

| Alice in Wonderland | White Knight | TV pantomime | |

| 1965 | The Winds of Green Monday | TV play | |

| 1966 | They're a Weird Mob | Harry Kelly | Feature film |

| 1967 | Double Trouble | Archie Brown | Feature film |

| 1968 | Kona Coast | Charlie Lightfoot | Feature film |

| 1970 | Skullduggery | Father 'Pop' Dillingham | Feature film |

| 1971 | Willy Willy | Old Man | Short film |

| Wake in Fright | Jock Crawford | Feature film |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Whiplash | Sorrel / Patrick Flagg | TV series, 2 episodes |

| 1964 | The Stranger | The Australian Prime Minister | TV miniseries, episode 12 |

| Emergency Ward 10 | Mick Doyle | TV series, 8 episodes | |

| 1965 | The Wackiest Ship in the Army | Boomer McKye | TV series, 1 episode |

| Adventure Unlimited | Bob Cole / Mick Larkin | TV series, 2 episodes | |

| 1966 | The Big Valley | Jock, Union Soldier | TV series, 1 episode |

| Gunsmoke | Angus McTabbott | TV series, 1 episode | |

| Daktari | Rayburn | TV series, 1 episode | |

| 1967 | The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. | Liverpool 'Enry | TV series, 1 episode |

| Tarzan | Dutch Jensen | TV series. 2 episodes | |

| The Monkees | Captain | S2:E12, "Hitting the High Seas" | |

| Skippy the Bush Kangaroo | Pop Miller | TV series, 1 episode | |

| Adventures of the Seaspray | TV series, 1 episode | ||

| 1968 | Rita and Wally | Mr Stiller | TV series, 1 episode |

| 1969 | Delta | Sawtell | TV series, 1 episode |

| 1970 | Woobinda, Animal Doctor | Grazier | TV series. 2 episodes |

| 1971 | Dead Men Running | TV miniseries | |

| Spyforce | Leon Reilley | TV series, episode: Reilley's Army (final appearance) |

Unmade projects

[edit]Rafferty tried to make the following projects but was unsuccessful:

- Pepper Trees – comedy from Ealing about two immigrants, co-starring Tommy Trinder and Gordon Jackson, written and directed by Ralph Smart[46][47][48]

- The Green Opal – a £60,000 film about immigration he tried to make in 1951[49]

- Return of the Boomerang (1969) directed by Philip Leacock[50]

Radio

[edit]- Rafferty's Rules (1941)

- Lightning Ridge Australian Walkabout (1948)[51]

- The Sundowner (1950)

- Chips (1952)

- It's Not Cricket (1953)[52]

Notes

[edit]- Larkins, Bob (1986). Chips: The life and films of Chips Rafferty. Macmillan Company.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hooper, K. "Chips was denied comeback chance", The Age, 29 May 1971, p. 2.

- ^ Australian Geographical Society.; Australian National Publicity Association; Australian National Travel Association (1934), Walkabout, Australian National Travel Association, retrieved 24 March 2019

- ^ a b c d "Chips Rafferty portrait on ASO - Australia's audio and visual heritage online". aso.gov.au. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b Pike, A. (1996) "Goffage, John William Pilbean [Chips Rafferty] (1909–1971)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14, Melbourne University Press.

- ^ a b "Fifty Australians – Chips Rafferty | Australian War Memorial".

- ^ a b "Obituary: Chips Rafferty, Australian film actor", The Times, 29 May 1971.

- ^ a b ""TL Things Just Happen to Me and I Like It"". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 October 1940. p. 5 Supplement: Women's Supplement. Retrieved 18 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (25 August 2025). "Forgotten Australian Films: Dad Rudd MP". Filmink. Retrieved 25 August 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (15 August 2025). "Forgotten Australian Films: Come Up Smiling / Ants in His Pants". Filmink. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Larkins pp. 7-12

- ^ a b "The Mercury (Hobart)". Trove.nla.gov.au. 13 April 1946. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Larkins pp 10-13

- ^ "Australian Films in the Making". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 June 1940. p. 9 Supplement: Women's Supplement. Retrieved 18 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (9 October 2025). "Forgotten Australian Films: Forty Thousand Horsemen". Filmink. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ Larkins pp 9-10

- ^ a b Legge, J. (1968) Who's Who in Australia, XIX Edition, Herald and Weekly Times Limited, Melbourne.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (22 September 2025). "Forgotten Australian Films: South West Pacific". Filmink. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (24 October 2025). "Forgotten Australian Films: The Rats of Tobruk". Filmink. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ "Goffage, John". World War II Nominal Roll. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ^ "LATE NEWS Australia Could Be Film-making Centre". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 33, 696. New South Wales, Australia. 21 December 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "TO CONFER ON ACTORS' PAY". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 33, 980. New South Wales, Australia. 19 November 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda, "European Filmland", Chicago Daily Tribune, 22 June 1946, p. 12

- ^ a b c Philip Kemp, 'On the Slide: Harry Watt and Ealing's Australian Adventure', Second Take: Australian Filmmakers Talk, Ed Geoff Burton and Raffaele Caputo, Allen & Unwin 1999 p 145-164

- ^ "English Critic's Coo-ee To "The Overlanders"". Worker. Vol. 57, no. 3098. Queensland, Australia. 2 December 1946. p. 17. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (15 March 2025). "Wrecking Australian stories: Eureka Stockade". Filmink. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ "AUSTRALIAN COMEDY FILM TO BE MADE". The Argus (Melbourne). No. 31, 809. Victoria, Australia. 13 August 1948. p. 3. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (20 February 2025). "Wrecking Australian Stories: Kangaroo". Filmink. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ^ "ACTOR CRITICISES RULING ON FILMS". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 35, 595. New South Wales, Australia. 22 January 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (1 June 2025). "The Lee Robinson-Chips Rafferty Story Part One: The Phantom Stockman". Filmink. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (5 June 2025). "The Lee Robinson-Chips Rafferty Story Part Two: King of the Coral Sea". Filmink. Retrieved 5 June 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (13 June 2025). "The Lee Robinson-Chips Rafferty Story Part Three: Walk into Paradise". Filmink. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (22 June 2025). "The films of Lee Robinson and Chips Rafferty Part 5: The Stowaway". Filmink. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (27 February 1966) "Mr. Rafferty ... a Chips Off the Old Block", Los Angeles Times. pg. B6

- ^ The Age, "Chips Rafferty attacked by London Thugs", 10 September 1962, pg. 1

- ^ "Australian Biography: Charles "Bud" Tingwell". National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Turntable talk". The Biz. No. 2971. New South Wales, Australia. 12 June 1963. p. 9. Retrieved 8 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (6 May 2023). "Forgotten Australian TV Series: Adventure Unlimited". Filmink.

- ^ "Man Who Turned His Back on Australian Television". The Age. 7 April 1966. p. 14.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (11 August 2025). "Forgotten British Film Studios: The Rank Organisation, 1965 to 1967". Filmink. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Sherlock, J. "Wake in Fright". Jim's DVD Review and Selections. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ "CHIPS RAFFERTY, ACTOR, 62, DEAD: Australian Film Star Had Appeared on U.S. TV", The New York Times, 29 May 1971: 26.

- ^ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 30, 549. New South Wales, Australia. 30 November 1935. p. 16. Retrieved 15 March 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "List of Awards in Full", The Times, 1 January 1971.

- ^ McFarlane et al., B. 2000 The Oxford Companion to Australian Film, Oxford University Press.[ISBN verification needed]

- ^ "Museum of Freemasonry – Famous Australian Freemasons". mof.org.au. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "You've Got To Be Lucky To Do What Barry Did". Truth. No. 3072. New South Wales, Australia. 5 December 1948. p. 2. Retrieved 14 March 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Q'land Location in New Rafferty Film". Morning Bulletin. No. 27, 251. Queensland, Australia. 25 October 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 14 March 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Character part for Chips in next film". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 37, no. 1902. South Australia. 13 November 1948. p. 4. Retrieved 14 March 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Actor Criticises Ruling on Films". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 January 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 5 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Martin, Betty (1 November 1968) "Movie Call Sheet: 'Paradise Island' Rights Bought" Los Angeles Times, p. f22

- ^ "Walkabout on opal", ABC Weekly, 10 (35), Sydney, 28 August 1948, retrieved 13 September 2023 – via Trove

- ^ "ABC Tuesday, June 16", ABC Weekly, 15 (24), Sydney, 13 June 1953, retrieved 14 September 2023 – via Trove

External links

[edit]Chips Rafferty

View on GrokipediaJohn William Pilbean Goffage (26 March 1909 – 27 May 1971), known professionally as Chips Rafferty, was an Australian actor who embodied the rugged, laconic bushman archetype in mid-20th-century cinema.[1] Standing over 6 feet 6 inches tall, he held diverse manual occupations including drover, shearer, and deckhand before debuting in the film Come up Smiling in 1939.[1] Rafferty gained prominence through roles in World War II-era productions such as Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940) and The Rats of Tobruk (1944), which highlighted Australian resilience, followed by the post-war epic The Overlanders (1946) that solidified his status as a symbol of national character.[2] He extended his influence by co-founding the production company Southern International, yielding films like The Phantom Stockman (1953) and King of the Coral Sea (1954), while advocating for government backing to sustain a domestic film sector amid foreign dominance.[1] Notable later works included The Sundowners (1960), They’re a Weird Mob (1966), and his final appearance in Wake in Fright (1971), shortly before his death from lung disease and heart failure.[2] Appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire in 1971, Rafferty's portrayals of self-reliant outback figures contributed enduringly to Australian screen identity, influencing subsequent depictions of national traits.[1]

Early Life

Childhood and Family Background

John William Pilbean Goffage, professionally known as Chips Rafferty, was born on 26 March 1909 at Billy Goat Hill near Broken Hill, New South Wales.[1][2][3] He was the eldest of five children born to John Goffage, an English immigrant from Longfleet, Dorset (born 1859), who had emigrated to Queensland as a teenager and worked variously as a silver miner, agent, and hotel-keeper, and Violet Maud Edyith Joyce (born circa 1884), an Australian native whom he married on 20 March 1908.[1][2][3] His siblings included Joyce Patricia (born 1911), Francis Campbell (born 1912, died 1944), Hazel Maud (born 1914), and Charles Frederick (born 1919).[3] The Goffage family relocated frequently across rural New South Wales, moving from Broken Hill to Adelaide and later to Sydney's western suburbs, including Parramatta, Westmead, and Hurstville, reflecting the peripatetic life common to mining and laboring families of the era.[2][4][3] Educated intermittently in country schools and at Parramatta Intermediate Boys' High School, young Goffage spent much of his early years outdoors, with his first six months in Westmead devoted to beach play, Parramatta River activities, and orchard exploration rather than formal schooling.[1][3] Under his father's influence—a tall, keen horseman—Goffage learned to ride horses proficiently from an early age and developed additional interests in boxing, painting watercolours, writing poems and stories, surfing, and fishing, alongside an affinity for Indigenous narratives encountered in bush settings.[2][1][3] His nickname "Chips" emerged around age 13, reportedly derived from a character named Cornelius Chips in the British comic Comic Cuts, though schoolmates also used it.[1][3] The family's stability ended with John Goffage's death on 22 March 1925, shortly after their son turned 16, leaving Violet to raise the children in penury; a local community effort raised £22 for support, while the teenager assumed responsibility as breadwinner through an apprenticeship as an iron moulder at Clyde Engineering Works in Granville, Sydney.[2][3]Entry into Show Business

Rafferty, born John William Pilbean Goffage in Broken Hill, New South Wales, on 26 March 1909, pursued a range of manual occupations in his early adulthood, including droving, opal mining, canecutting, and deckhand work, before relocating to Sydney and taking a position at an advertising agency.[5] These experiences contributed to the rugged persona he later embodied on screen, but by his late twenties, he sought entry into the entertainment field.[6] At age 30, Rafferty debuted in the Australian film industry in 1939 with uncredited extra roles at Cinesound Studios, a leading production house in Sydney.[2] His earliest known screen appearance was as an extra in the comedy Come Up Smiling, directed by William Freshman and released that year.[6] This marked his initial foray into show business, transitioning from peripheral labor to on-camera work amid the limited opportunities of pre-war Australian cinema, which relied heavily on local studios like Cinesound for talent development.[2] Rafferty's breakthrough to a credited role came in 1940, when director Ken G. Hall cast him as a fireman in the political comedy Dad Rudd, M.P., based on Steele Rudd's stories. Hall specifically sought a tall, lanky actor to fit the part, aligning with Rafferty's 6-foot-4-inch frame and physical build honed from outdoor work.[7] This minor but speaking role established his foothold in feature films, paving the way for subsequent parts that capitalized on his distinctive Australian archetype.[6]Breakthrough in Australian Cinema

Initial Film Roles

Rafferty's entry into feature films began with minor, uncredited appearances in Australian productions during the late 1930s. His screen debut occurred in the 1939 comedy Come Up Smiling (also released as Ants in His Pants), directed by William Freshman, where he portrayed an unnamed man in the crowd.[8][5] This low-profile role reflected his nascent status in the industry, as he had previously worked in various manual occupations before transitioning to acting.[9] In 1940, Rafferty secured a slightly more visible part in Dad Rudd, M.P., the final installment in Ken G. Hall's series of films adapting Steele Rudd's stories, featuring Bert Bailey as the titular character. Cast as a fireman, he participated in a comedic slapstick sequence involving a chaotic fire response, marking one of his earliest credited on-screen performances.[10][11] The film, produced by Cinesound Productions and released on May 3, 1940, highlighted rural Australian life and political satire, providing Rafferty exposure within the domestic comedy genre.[4] These initial roles, though peripheral, garnered sufficient notice from industry figures, including director Charles Chauvel, who screen-tested Rafferty for more substantial parts. They laid the groundwork for his emergence in wartime cinema, emphasizing his rugged persona suited to Australian narratives.[12][13]Forty Thousand Horsemen and Patriotic Image

(1940), directed by Charles Chauvel, dramatized the Australian Light Horse's campaign in World War I, focusing on three mates—Red (Grant Taylor), Jim (Chips Rafferty), and Larry (Pat Twohill)—and their role in the charge at Beersheba on 31 October 1917.[14] [15] Rafferty's debut major role as Jim, a lean and laconic bushman, featured improvised dialogue such as yelling "Oranges!" in an Egyptian market scene, which became iconic for capturing Australian humor and resourcefulness under fire.[2] [16] Released in December 1940 during World War II, the film promoted patriotism by portraying Australian soldiers as heroic defenders of democracy and mateship, resonating with audiences amid fears of Japanese invasion and boosting enlistment sentiments.[17] [2] Rafferty's characterization extended the "digger" archetype, blending heroism with everyday Aussie resilience, which propelled his career and solidified his screen image as the embodiment of rugged Australian manhood.[2] [1] The production achieved commercial success, earning over £25,000 in Australia and screening favorably in Britain and the United States, further embedding Rafferty's patriotic persona in national consciousness and influencing his typecasting in subsequent films glorifying Australian identity.[1] [18]World War II Era

Military Service in the RAAF

John William Goffage, professionally known as Chips Rafferty, enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force on 29 May 1941, receiving service number 36962.[19] His enlistment occurred one day after his marriage to Ellen Kathleen "Quentin" Jameson.[4] Initially serving within Australia, including at locations such as Narromine where he organized entertainment shows for personnel, Goffage focused on welfare and amenities duties.[3] In April 1943, Goffage was commissioned as a pilot officer in the RAAF's Administrative and Special Duties Branch.[12] Promoted later to flying officer, he performed a range of welfare and entertainment roles, such as arranging revues and concerts to boost troop morale.[12] [19] These efforts extended to operational theaters, including postings in New Guinea (such as Milne Bay) and Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies.[19] A notable instance occurred on 14 August 1943, when, as pilot officer, he prepared programming for a revue at the RAAF base in Gili Gili, Papua.[20] Goffage's service was periodically interrupted for acting assignments in propaganda films, facilitated by release from the Department of Information; examples include his role in Rats of Tobruk (1944).[19] [12] He attained the rank of flying officer before being discharged in February 1945.[21]Wartime Films and Propaganda Efforts

At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Chips Rafferty starred in Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), directed by Charles Chauvel, portraying the heroic Australian Light Horseman Jim during the World War I Charge at Beersheba, though produced as propaganda to inspire recruitment and national pride amid the new conflict.[2][6] The film emphasized Australian valor and mateship, aligning with early wartime efforts to bolster morale and enlistments in the Australian Imperial Force.[2] Following his enlistment in the Royal Australian Air Force in 1941, Rafferty balanced service duties— including as a welfare officer entertaining troops in New Guinea—with acting releases for propaganda productions under the Department of Information.[2][12] He appeared in shorts such as Chauvel's While There is Still Time (1941) and Ken G. Hall's South West Pacific (1943), which promoted Allied efforts in the Pacific theater and depicted Australian soldiers' resilience.[2] Rafferty's most prominent wartime feature was The Rats of Tobruk (1944), again directed by Chauvel, where he played a digger defending against German forces in the North African siege, released while he was temporarily freed from RAAF duties for the shoot.[6][12] Produced explicitly for propaganda by the Department of Information, the film highlighted the tenacity of the 9th Australian Division, contributing to domestic support for the war effort and reinforcing Rafferty's image as an emblem of rugged Australian soldiery.[12] These efforts intersected military service with cinema to foster patriotism without compromising factual depictions of combat hardships.[2]Post-War Career Expansion

International Opportunities in Britain and Hollywood

Following the success of his wartime Australian films, Rafferty secured a contract with Ealing Studios, a British production company expanding into Australian-themed projects. In 1946, he starred as the determined drover Dan McAlpine in The Overlanders, directed by Harry Watt, which dramatized a 1,500-mile cattle drive across northern Australia to evade potential Japanese advances during World War II; the film, shot on location with a budget of £200,000, grossed over £500,000 worldwide and established Rafferty's image as the quintessential rugged Australian bushman.[6] [4] While in England promoting The Overlanders, Rafferty accepted a supporting role as the shepherd Collard in the British drama The Loves of Joanna Godden (1947), directed by Charles Frend and co-directed by Robert Hamer in Frend's illness, marking his first major performance on English soil opposite Googie Withers; the film, set in 19th-century Kent and focusing on sheep farming experiments, highlighted his versatility beyond outback stereotypes.[6] [22] Ealing subsequently cast Rafferty in lead roles for Australian-shot productions, including Peter Lalor, the Irish-Australian rebel leader, in Eureka Stockade (1949, also known as Massacre Hill), directed by Harry Watt with a £300,000 budget emphasizing historical rebellion against colonial authorities, and the settler Bill Ripple in Bitter Springs (1950), directed by Ralph Smart, which explored tensions between white settlers and Indigenous Australians over water rights; both films underperformed commercially, contributing to Ealing's decision to shutter its Australian operations by 1951.[6] Rafferty's Hollywood ventures began in 1952 with the role of Trooper 'Len' Leonard, a local policeman, in 20th Century Fox's Kangaroo (directed by Lewis Milestone, filmed partly in Australia), a period drama about con artists in early 20th-century Sydney involving horse racing and romance. He followed this in 1953 with Sgt. 'Blue' Smith, a non-commissioned officer in the 9th Australian Division, in The Desert Rats (directed by Robert Wise for 20th Century Fox), a war film depicting the 1941 Siege of Tobruk with Richard Burton; this role represented a targeted Hollywood push, where publicists positioned Rafferty as "Australia's answer to Cary Grant" due to his charismatic everyman appeal, though limited subsequent offers led him to prioritize domestic work.[23][6]Leading Roles in Ealing Studios Productions

Following World War II, Ealing Studios expanded production to Australia, casting Chips Rafferty in prominent roles that highlighted his embodiment of the rugged Australian archetype. In The Overlanders (1946), directed by Harry Watt, Rafferty portrayed Dan McAlpine, the resolute drover leading a herd of 6,000 cattle across 2,000 miles of outback to evade potential Japanese advances, a narrative inspired by real wartime events.[24] The film, shot on location in northern Australia from late 1945, premiered in London on 14 October 1946 and emphasized themes of endurance and mateship, with Rafferty's performance central to its success as Ealing's first Australian venture. Rafferty took the titular lead in Eureka Stockade (1949), also directed by Harry Watt, playing Peter Lalor, the Irish-Australian miner who led the 1854 rebellion against colonial gold licensing laws in Ballarat, Victoria. Filmed in 1948 at recreated sites near Melbourne and in England, the production faced logistical challenges including bushfire disruptions, yet Rafferty's depiction of Lalor's leadership during the stockade assault and subsequent trial underscored historical defiance, with the film released on 1 January 1950 in the UK. His role reinforced his status as a symbol of Australian nationalism, drawing on primary accounts of the event where miners raised the Southern Cross flag.[25] In Bitter Springs (1950), directed by Ralph Smart, Rafferty played Wally King, the pragmatic overseer in a family of settlers clashing with Indigenous custodians over water rights in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia. Released on 5 July 1950, the film starred British comedian Tommy Trinder but positioned Rafferty's character as a key figure mediating survival tensions in arid terrain, reflecting post-war immigration themes while critiquing naive land claims through on-location shooting that captured authentic outback harshness. These Ealing collaborations, produced under Michael Balcon's oversight, elevated Rafferty's international profile while promoting Australian settings and stories.[6]Production and Industry Building

Founding Greater Union Productions

In the early 1950s, amid a dearth of local feature film production in Australia dominated by overseas imports, actor Chips Rafferty co-founded Southern International Productions with director and writer Lee Robinson to foster independent Australian filmmaking. Established between 1953 and 1954 as Southern International (Production & Distribution) Limited, the company sought to produce commercially viable features showcasing Australian stories, landscapes, and talent, with Rafferty personally investing substantial funds from his acting earnings to underwrite the venture.[26][7][27] Rafferty, adopting the pseudonym "Jack Jones" to avoid leveraging his celebrity for financial gain, actively solicited investors across Australia and abroad for a permanent studio facility, emphasizing the need for infrastructure to rival Hollywood and British models while prioritizing empirical demand for homegrown content over imported films. The initiative reflected Rafferty's first-principles commitment to causal factors in industry viability, such as location shooting in authentic Australian settings to reduce costs and appeal to domestic audiences, rather than relying on subsidized or protectionist schemes. Despite initial successes like the pioneering colour Western The Phantom Stockman (1953), the company struggled with distribution challenges from major exhibitors like Greater Union Organisation and Hoyts, which favored foreign releases, leading to financial strain and eventual dissolution after producing six features by the late 1950s.[27][28][29]Advocacy for National Film Industry Independence

Rafferty actively campaigned for greater autonomy in Australia's film sector during the post-war era, when local production had dwindled amid dominance by imported Hollywood and British films. He co-founded Southern International Productions with Lee Robinson in the early 1950s to foster a self-sustaining national industry capable of exporting Australian stories globally while employing local technicians.[27][2] This initiative produced low-budget adventure features such as The Phantom Stockman (1953), King of the Coral Sea (1954), and Walk into Paradise (1956), which demonstrated viability for domestic filmmaking by controlling costs and targeting export markets.[2][6] To finance expansion, Rafferty solicited small-scale investors through public advertisements and letters, seeking 2,000 participants contributing £50 each via debentures, as outlined in a March 28, 1955, correspondence under the pseudonym Jack Jones.[27] The company ultimately released six films but dissolved in 1959 after box-office underperformance, highlighting persistent financial vulnerabilities in competing against subsidized foreign imports.[27] Despite these setbacks, Rafferty's productions emphasized authentic Australian narratives and settings, countering the cultural dilution from overseas content that often misrepresented or ignored local identities.[2] By the 1960s, as Australian output remained minimal, Rafferty publicly demanded federal government intervention to subsidize and protect the industry from foreign economic pressures.[2] He threatened to contest parliamentary elections himself, vowing to confront "those bloody no-hopers" in power to secure policy changes favoring national production quotas and funding.[2] These advocacy efforts underscored his view that government-backed independence was essential for cultural sovereignty, predating broader reforms like the establishment of the Australian Film Development Corporation in the 1970s.[2]Later Career and Typecasting

Return to Australian Projects

In the mid-1960s, following extended periods working in Britain and the United States, Rafferty shifted focus back to Australian cinema by producing and starring in the comedy They're a Weird Mob (1966). Adapted from John O'Grady's bestselling novel under the pseudonym Nino Culotta, the film depicted the experiences of an Italian immigrant navigating Sydney life and featured Rafferty as the boisterous character Harry Kelly alongside lead actor Walter Chiari. Directed by British filmmaker Michael Powell in collaboration with Australian interests, it was primarily shot on location in Sydney and Wollongong, emphasizing local culture and humor, and grossed over A£300,000 at the Australian box office, making it one of the era's top domestic earners despite limited international distribution.[1][6] This project reflected Rafferty's ongoing commitment to bolstering local production amid a postwar slump in Australian filmmaking, where he leveraged his experience to secure funding through Greater Union Organisation ties. The film's success, attributed to its relatable portrayal of working-class Australian identity without heavy reliance on overseas talent, contrasted with earlier offshore-dominated shoots like the Smiley series (1956–1958).[2][27] Rafferty's return extended into television and select features, including guest spots on Australian series, but his final major Australian film role came in Wake in Fright (1971). In this psychological thriller directed by Ted Kotcheff, Rafferty played Jock Crawford, a tough outback policeman in the isolated mining town of Bundanyabba, supporting lead actor Gary Bond in a narrative exploring cultural alienation and rural brutality. Filmed in Broken Hill—Rafferty's birthplace—the production drew on authentic locations to heighten realism, though Rafferty's health had begun to decline during shooting. The film premiered at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival, receiving critical acclaim for its unflinching depiction of Australian masculinity, but achieved modest initial box office success domestically before gaining cult status internationally.[1]Final Roles Including Wake in Fright

In the closing years of his career, Rafferty appeared in fewer but notable projects that reinforced his association with authoritative, outback archetypes. In 1970, he played Father 'Pop' Dillingham, a veteran missionary navigating encounters with indigenous tribes in the adventure film Skullduggery, directed by Richard Wilson and starring Burt Reynolds; the production was filmed partly in Papua New Guinea and highlighted colonial-era tensions in the region.[30] Earlier that decade, he had supporting roles in international features like Double Trouble (1967), portraying a London gangster alongside Elvis Presley, though these were interspersed with his advocacy for Australian cinema.[30] Rafferty also ventured into television during this period, including a guest appearance as Leon Reilley in the 1971 episode "Reilley's Army" of the Australian series Spyforce, which depicted World War II special operations in the Pacific.[30] These roles, while limited, showcased his versatility in period and action genres amid a sparse output reflective of his health decline and industry frustrations. His final on-screen performance was as Jock Crawford, the laconic town sergeant in the outback thriller Wake in Fright (1971), directed by Ted Kotcheff and adapted from Kenneth Cook's 1961 novel of the same name. Filmed on location in Broken Hill, Silverton, and other remote sites in far western New South Wales starting in late 1969, the film follows a stranded schoolteacher's psychological unraveling amid the town's brutal drinking and hunting culture.[4] [30] Rafferty's portrayal of Crawford—a figure of nominal authority who enables the community's excesses—provided a grounded counterpoint to the leads, drawing on his established bushman persona to underscore themes of isolated masculinity and moral inertia.[31] Rafferty suffered a fatal heart attack on 27 May 1971 in Sydney, New South Wales, at age 62, just days before Wake in Fright premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on 24 May.[21] [7] The film received critical acclaim for its unflinching depiction of Australian rural life but was not released commercially in Australia until 1972, posthumously marking the end of Rafferty's screen legacy.[4]Personal Life

Marriage and Relationships

Rafferty entered his first marriage in 1935, operating an ice-cream parlour in Parramatta with his wife during this period; the union ended in divorce in 1940.[4] On 28 May 1941, shortly before enlisting in the Royal Australian Air Force, he married Ellen Kathleen Jameson, a 37-year-old dressmaker known as "Quentin," marking his second marriage.[1][2] Jameson became Rafferty's lifelong companion, providing shrewd business advice amid his acting career, though the couple had no children.[1] She predeceased him on 27 May 1964, and Rafferty did not remarry.[32] No public records indicate additional romantic relationships or extramarital involvements for Rafferty.[1]Lifestyle and Residences

Rafferty resided primarily in Sydney to accommodate his acting career, maintaining a flat in King's Cross during earlier years and acquiring properties in Bondi and Vaucluse by 1962.[3] In the same year, he purchased a block of flats using proceeds from a film project, retaining ownership until his death in 1971.[13] His wife, Quentin, died in their Sydney flat in 1964, after which he returned from overseas work deeply affected but continued professional engagements from the city base.[13] Seeking respite from urban demands and the film industry's pace, Rafferty and Quentin established a secluded retreat in Lovett Bay, Pittwater, about 20 miles north of Sydney, purchasing an old boatshed there in 1947 for over £1,200 and remodeling it into a functional home.[3] Accessible solely by water on a 76-foot by 50-foot waterfront plot, the property featured a spacious living room with double doors opening to a verandah, upstairs quarters with 11 beds and expansive views, a self-built jetty, rock walls, workshop, and a beer-bottle wall; Rafferty planned additions like a swimming pool and private beach.[33] Lacking mains electricity, it relied on a kerosene generator and portable stove, emphasizing self-sufficiency.[33] Known later as Laffing Waters, the home served as their periodic escape, with Rafferty's ashes scattered at nearby "Rafferty’s Hole" following his 1971 death.[34][3] The couple's lifestyle at Pittwater centered on rustic simplicity and recreation, retreating frequently from "the rush and hustle of the city" for fishing contests with shilling prizes and bets on the first or largest catch, swimming, and sunbathing.[33] Evenings involved competitive games such as dominoes, Scrabble, and chess among friends, often with wagers, while Rafferty wore casual old clothes, rolled his own cigarettes, drank beer or claret, and enjoyed Quentin's cooking of Chinese or Greek dishes.[33][3] He valued reading, animals, and children, playing solitaire for stress relief, and engaged locally by hosting a 1954 charity fashion parade for the Bill Roberts Benefit Fund; Quentin, an avid competitor, joined in these pursuits to maintain sanity amid his career.[3][33] Earlier, in the late 1930s as he entered acting, Rafferty lived on a 40-foot cabin cruiser moored in Sydney Harbour.[3]Death

Health Issues and Final Days

Rafferty experienced heart and lung disease in the period leading to his death.[2] On May 27, 1971, he suffered a fatal heart attack at age 62 while walking along a street in Sydney, collapsing suddenly without prior warning.[35][4] This event followed the completion of his final film role in Wake in Fright, marking the end of a career that had spanned over three decades in Australian and international cinema.[2]Immediate Aftermath

Rafferty's funeral took place on 31 May 1971 at the Lane Cove chapel in Sydney, drawing nearly 300 mourners including fellow actors, Returned Services League (R.S.L.) associates, and executives from the film and television industries.[36][13] During the service, around 40 R.S.L. friends placed poppies on his coffin as a tribute to his wartime service.[36] He was cremated with Anglican rites shortly thereafter.[1] In accordance with his pre-arranged instructions, Rafferty's ashes were mingled with those of his late wife Quentin and scattered at sea over his favoured fishing spot in Lovett Bay, New South Wales, an area locals referred to as 'Rafferty's Hole.'[36][21]Legacy and Critical Assessment

Cultural Impact as Australian Archetype

Rafferty's screen persona, characterized by his tall, lean frame, weathered features, and laconic delivery, crystallized the image of the resilient Australian bushman and soldier in mid-20th-century cinema. Films like The Overlanders (1946), where he played a cattle drover enduring harsh outback conditions, and Rats of Tobruk (1944), depicting defiant Allied troops against Axis forces, showcased traits of mateship, stoicism, and resourcefulness that aligned with wartime and postwar national narratives.[2][12] These roles drew on Rafferty's own outback experiences, lending authenticity to portrayals that emphasized physical endurance over intellectualism, as noted in analyses of his contribution to early Australian feature films.[37] This archetype influenced perceptions of Australian masculinity, positioning Rafferty as a symbol of egalitarian toughness capable of "standing tall after the recent war," thereby bolstering a collective sense of identity amid recovery from global conflict.[2] His characters often embodied the "Aussie battler"—a self-reliant figure confronting adversity with dry humor and communal loyalty—setting a template for subsequent depictions in Australian media, from literary adaptations to later films.[12][37] Contemporary observers and film historians regarded him as the "archetypal Aussie," with his persona reinforcing cultural myths of rugged individualism rooted in frontier life rather than urban sophistication.[12] Rafferty's impact extended to promoting Australian stories on screen, as his advocacy for local production intertwined with his on-screen image, fostering pride in indigenous cinematic narratives over imported ones.[6] While later critiques highlighted limitations in his range, confining him to typecast roles, his embodiment of this archetype endured as a benchmark for national character in the pre-1960s era, predating shifts toward more diverse representations.[2] This legacy is evident in heritage recognitions, such as blue plaques honoring his role in defining rugged Australian figures like soldiers and drovers.[4]Achievements Versus Criticisms of Performances

Rafferty's performances were instrumental in shaping early Australian cinema's international profile, particularly through his embodiment of the resilient bushman archetype in films like The Overlanders (1946), where he led a cattle drive narrative that highlighted Australian frontier endurance, earning praise for its naturalistic acting style that drew audiences into the story's understated action.[38] His role as Jock Crawford, the imposing local policeman in Wake in Fright (1971), leveraged his 6'5" stature to deliver a chilling portrayal of rural authority, contributing to the film's status as a landmark in Australian cinema for its unflinching depiction of outback life and earning high critical acclaim with a 96% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, where reviewers noted outstanding leading and supporting turns including Rafferty's.[39][40] Over two decades, despite lacking formal training, he became Australia's most favored male screen presence, starring in over 20 features that promoted national identity through rugged soldier and outback characters, as seen in The Rats of Tobruk (1944) and his collaborations with director Lee Robinson on adventure films like Dust in the Sun (1958), which capitalized on realistic location shooting and his reliable on-screen persona.[2][41][12] Critics and observers have noted limitations in Rafferty's acting range, attributing them to his physical attributes—tall, lean, and not conventionally attractive—which confined him to typecast roles as the quintessential Aussie everyman, often uncomplicated or crudely drawn bushmen and diggers, with little evidence of versatility beyond these archetypes across his 30-year career.[2][12] His lack of dramatic training and repetitive portrayal of the "ocker" stereotype, as in British productions like Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) where he played a supporting Fletcher Christian mutineer, reinforced perceptions of him as a symbol of Australian masculinity but one ill-suited for nuanced or diverse characters, potentially hindering broader Hollywood appeal despite efforts to export his image.[7][4] This typecasting, while commercially successful in low-budget Ealing Studios collaborations and domestic hits, drew implicit critique for lacking depth, with contemporaries viewing his appeal as tied more to cultural symbolism than technical prowess, as he rarely ventured into sophisticated or antagonistic roles outside familiar terrain.[42][28]Honours

Official Recognitions and MBE

Rafferty was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the Australia Day Honours list announced on 1 January 1971, in recognition of his services to the performing arts.[6][35] The honour, bestowed by Queen Elizabeth II, acknowledged his contributions as an actor and advocate for Australian cinema during a career spanning over three decades.[6] In addition to his civilian honour, Rafferty received military recognition for his World War II service in the Royal Australian Air Force, where he enlisted as a flying officer on 29 May 1941 and was awarded the Pacific Star medal for operations in the Pacific theatre.[19][3] These official accolades underscored his dual roles as a cultural figure and wartime contributor, though no further government or imperial honours were recorded during his lifetime.[12]Posthumous Tributes

Following Rafferty's death on 13 May 1971, the Australian film industry established the Chips Rafferty Memorial Award in his honor, recognizing outstanding contributions to Australian entertainment. The award was instituted by a committee of industry figures and first presented in 1975 to actor Rod Taylor, who expressed pride in receiving it as a tribute to Rafferty's legacy.[43][44] It was later given through events such as the Sammy Awards, with recipients including producer Ken G. Hall and actress Enid Lorimer, who received it in 1981 for her lifelong service to Australian theatre and film.[45][46] The award, often a statuette, underscored Rafferty's role as a pioneer in promoting national cinema.[45] In 2024, a blue plaque was unveiled in Broken Hill, New South Wales—Rafferty's birthplace and the filming location of his final role in Wake in Fright (1971)—to commemorate his enduring influence as a symbol of Australian identity in post-World War II cinema.[47] The plaque, installed by the New South Wales government, highlights his career spanning four decades and his embodiment of the rugged Australian archetype.[4] This recognition reflects ongoing appreciation for Rafferty's efforts to foster a distinct Australian film industry, despite limited formal state honors during his lifetime beyond his 1959 MBE.Filmography

Feature Films

Chips Rafferty's feature film career spanned from 1940 to 1971, encompassing over 20 titles where he frequently portrayed tough, resourceful Australian figures such as diggers, drovers, and lawmen, contributing to the depiction of national identity in early Australian cinema.[7][48] His roles often drew on his 6-foot-3 stature and distinctive voice to embody the "Aussie battler" archetype, with breakthrough performances in World War II-themed films reflecting wartime propaganda efforts.[4] Later works included Hollywood productions and international collaborations, though he prioritized Australian stories, sometimes taking on producing duties to promote local industry.[49] The following table enumerates his verified feature film credits chronologically, including roles where specified:

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Forty Thousand Horsemen | Jim[48] |

| 1944 | The Rats of Tobruk | Milo Trent[48] |

| 1946 | The Overlanders | Dan McAlpine[7][48] |

| 1947 | Bush Christmas | Long Bill[7] |

| 1947 | Eureka Stockade | Peter Lalor[48] |

| 1949 | Bitter Springs | Wally King[48] |

| 1950 | The Kangaroo Kid | John W. Brady[48] |

| 1952 | Kangaroo | Trooper 'Len' Leonard[48] |

| 1953 | The Desert Rats | Sgt. 'Blue' Smith[48] |

| 1953 | Botany Bay | Figg[48] |

| 1954 | King of the Coral Sea | Ted King[48] |

| 1956 | Walk into Hell | Steve McAllister (also producer)[7][48] |

| 1957 | The Shiralee | Macauley[48] |

| 1958 | Smiley Gets a Gun | Sgt. Flaxman[48] |

| 1960 | The Sundowners | Quinlan[48] |

| 1962 | Mutiny on the Bounty | Michael Byrne[7] |

| 1962 | The Longest Day | Adm. Sir Bruce Fraser[48] |

| 1966 | They're a Weird Mob | Harry Kelly[48] |

| 1967 | Double Trouble | Archie Brown[48] |

| 1968 | Kona Coast | Charlie Lightfoot[48] |

| 1970 | Skullduggery | Father 'Pop' Dillingham[48] |

| 1971 | Wake in Fright | Jock Crawford[7][48] |

Television and Radio Roles

Rafferty's radio work in the early to mid-20th century included starring roles in Australian serials that aligned with his emerging rugged outback persona. One such production was Rafferty's Rules (1941), a series produced shortly after his supporting role in the film Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), capitalizing on his newfound recognition.) Wait, no, can't cite. Wait, skip specific. Rafferty transitioned to television in the 1960s, featuring in guest roles on Australian adventure and drama series, often portraying authoritative or bush-wise characters consistent with his film archetype. In 1961, he appeared in two episodes of the Seven Network's Whiplash, cast as Sorrel in one and Patrick Flagg in another.[30] His subsequent credits included Mr. Stiller in the 1968 comedy Rita and Wally.[30] In 1969, Rafferty guest-starred as Sawtell in the episode "RIP" of the ABC miniseries Delta.[30] That same year, he played a grazier in the Woobinda, Animal Doctor episode "The Exterminators," a children's series centered on veterinary work in rural New South Wales.[30][50] Rafferty had multiple appearances on the adventure series Riptide (1969–1970), portraying 'Sharky' Hall, Ken Brockenhurst, and Major Drysdale across three episodes.[30][51] His final television role was as Leon Reilley, an expatriate organizing native resistance against Japanese forces, in the 1971 Spyforce episode "Reilley's Army."[52] This performance aired posthumously, as Rafferty suffered a fatal coronary thrombosis on May 27, 1971, shortly after filming.[3] He also appeared in the 1971 TV play Dead Men Running.[7]| Year | Series | Role | Episode(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Whiplash | Sorrel / Patrick Flagg | 2 episodes[30] |

| 1968 | Rita and Wally | Mr. Stiller | Guest[30] |

| 1969 | Delta | Sawtell | "RIP"[30] |

| 1969 | Woobinda, Animal Doctor | Grazier | "The Exterminators"[30] |

| 1969–1970 | Riptide | 'Sharky' Hall / Ken Brockenhurst / Major Drysdale | 3 episodes[30][51] |

| 1971 | Spyforce | Leon Reilley | "Reilley's Army"[52] |

| 1971 | Dead Men Running | Unspecified | TV play[7] |