Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Chirp.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chirp

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Chirp

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

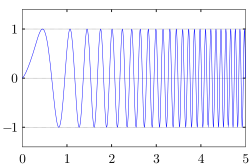

A chirp is a signal in which the instantaneous frequency varies continuously with time, typically increasing (up-chirp) or decreasing (down-chirp) in a monotonic fashion, often resembling the sound of a bird's call from which the term derives.[1][2]

Chirp signals are fundamental in signal processing and engineering applications due to their ability to achieve high time-bandwidth products, enabling better resolution in time and frequency domains compared to fixed-frequency pulses. The most prevalent form is the linear chirp, where the frequency sweeps linearly from an initial value to a final value over a defined duration, but other variants include quadratic, logarithmic, and exponential chirps that alter the frequency in nonlinear ways.[3][4]

In radar and sonar systems, chirps serve as transmitted waveforms to facilitate pulse compression, which enhances range resolution and signal-to-noise ratio without requiring high peak power, thus allowing detection of targets at greater distances or in cluttered environments. For instance, CHIRP (Compressed High-Intensity Radiated Pulse) technology in sonar transmits a sequence of frequencies to produce clearer images of underwater objects by distinguishing echoes based on their time delays. Similarly, in automotive radar, linear frequency-modulated chirps enable simultaneous estimation of range and relative velocity (Doppler shift) for advanced driver-assistance systems, supporting features like adaptive cruise control and collision avoidance.[5][6][7]

Beyond sensing technologies, chirp-based modulation finds use in communications, particularly chirp spread spectrum (CSS), a technique that spreads the signal across a wide bandwidth using up-chirps or down-chirps to improve robustness against interference, multipath fading, and low-power requirements, making it suitable for Internet of Things (IoT) devices and long-range wireless networks. In photonics and laser systems, chirped pulses—where the frequency varies across the pulse duration—are critical for chirped pulse amplification (CPA), a method that stretches, amplifies, and compresses ultrashort laser pulses to achieve high peak powers without damaging optical components, revolutionizing applications in micromachining, medical imaging, and fusion research.[8][9][10]

where is the initial frequency at , and for an up-chirp (increasing frequency) or for a down-chirp. This formulation ensures exponential growth or decay in frequency, contrasting with additive changes in other chirp types. The phase of the exponential chirp is derived by integrating the instantaneous angular frequency from 0 to :

The resulting signal form is

where is the constant amplitude and is an optional initial phase offset (often set to 0). This phase structure arises directly from the exponential frequency profile, leading to a nonlinear accumulation of oscillations that accelerates with time for up-chirps. Key properties of the exponential chirp include a linear frequency progression when plotted on a logarithmic scale versus time, which yields a constant relative bandwidth . This constant relative rate makes it ideal for applications requiring uniform coverage across multiplicative frequency ranges, such as octave-spanning signals where the sweep rate can be specified in octaves per second. For instance, the logarithmic nature ensures equal time allocation per octave, unlike linear chirps that devote more time to higher frequencies.[19] As a representative example, consider generating an exponential chirp sweeping from 100 Hz to 10 kHz over 1 second. Here, Hz, the final frequency Hz at s, so . Equivalently, with , spanning approximately 6.64 octaves at a rate of 6.64 octaves per second. This setup produces a signal with rapidly increasing perceived pitch, emphasizing the logarithmic scaling.[20]

Fundamentals

Definition

A chirp is a signal in which the frequency changes continuously with time, often increasing or decreasing monotonically.[1] Unlike constant-frequency signals such as pure tones, which maintain a fixed frequency throughout their duration, a chirp's instantaneous frequency varies over a specified range.[4] The term "chirp" derives from the short, sharp vocalization produced by birds or insects and was adopted in signal processing during the mid-20th century to describe these frequency-modulated waveforms, owing to the analogous sound generated upon demodulation to audio frequencies.[11][12] This nomenclature first appeared prominently in technical literature around 1960, associated with advancements in radar signal design at Bell Telephone Laboratories.[13] Chirps are qualitatively described by their direction of frequency sweep: an up-chirp rises from a lower to a higher frequency, while a down-chirp falls from higher to lower.[1]Mathematical Representation

A chirp signal is generally represented in the time domain as , where is the amplitude and is the instantaneous phase function that encodes the frequency variation over time.[1] This form captures the essence of a frequency-modulated signal where the phase evolves nonlinearly, distinguishing chirps from constant-frequency sinusoids. Equivalently, the signal can be expressed using sine, , as the choice between cosine and sine is a phase shift convention.[14] The instantaneous frequency of the chirp is defined as the time derivative of the phase divided by , that is, .[14] This definition arises from the interpretation of the phase's rate of change as the local angular frequency , with . For frequency-modulated chirps, a common phase representation is the quadratic form , where is the starting frequency and is the chirp rate determining the linear frequency sweep; this serves as a foundational model that can be generalized to higher-order polynomials for more complex sweeps.[1] In ideal chirp signals, the amplitude is typically held constant to focus on frequency modulation, though amplitude modulation can be incorporated as for practical variants without altering the core chirp structure.[1] A key metric for assessing chirp signal efficiency is the time-bandwidth product , where is the signal duration and is the swept bandwidth, quantifying the signal's capacity to achieve high resolution in applications like pulse compression.[1] This product highlights the chirp's advantage over simple pulses, as larger values enable greater compression gain while maintaining low sidelobes in matched filtering.Types

Linear Chirp

A linear chirp is a signal whose instantaneous frequency increases or decreases at a constant rate over time, making it the most fundamental and commonly used form of chirp signal. The instantaneous frequency is defined as , where is the initial frequency, is the constant chirp rate, and is time, typically for with being the signal duration. The chirp rate is calculated as , where is the final frequency, determining the linear sweep across the frequency band from to .[15] The phase function of a linear chirp derives from integrating the instantaneous frequency, yielding , which introduces a quadratic term characteristic of the linear frequency progression.[16] This quadratic phase distinguishes the linear chirp from constant-frequency signals and enables its representation as a frequency-modulated waveform. The time-domain expression for the linear chirp signal is given by for , where is the amplitude, often set to 1 for normalized signals.[16] This form assumes a real-valued cosine carrier, though complex exponential variants are used in analytical contexts. The constant sweep rate of the linear chirp results in a quadratic phase profile, which simplifies processing in applications requiring predictable frequency evolution. This property makes linear chirps ideal for matched filtering, where the filter's impulse response mirrors the signal's conjugate time-reversed form to achieve pulse compression and improve signal-to-noise ratio.[17] The bandwidth occupied by the signal approximates , providing a straightforward measure of its spectral extent.[15] As an example, consider a linear chirp starting at kHz and ending at kHz over second, yielding a chirp rate of kHz/s; this configuration sweeps through 9 kHz of bandwidth in a simple, uniform manner.[18]Quadratic Chirp

A quadratic chirp is a signal whose instantaneous frequency varies quadratically with time, resulting in a nonlinear frequency sweep that accelerates or decelerates. The instantaneous frequency is defined as , where is the initial frequency and is the quadratic chirp rate, typically for with the signal duration. The chirp rate is calculated as , where is the final frequency, leading to a parabolic frequency progression.[3] The phase function derives from integrating the instantaneous frequency: , introducing a cubic phase term that reflects the quadratic frequency variation. This cubic phase distinguishes quadratic chirps from linear ones and is useful in applications requiring nonlinear frequency modulation. The time-domain expression for the quadratic chirp signal is for , where is the amplitude, often normalized to 1. This assumes a real-valued cosine carrier, with complex forms used analytically. Key properties include the accelerating (for positive ) or decelerating frequency change, which can provide more uniform energy distribution in certain nonlinear systems or enhance resolution in advanced signal processing. The bandwidth is approximately , but the nonlinear nature affects spectral properties differently from linear chirps.[3] As an example, a quadratic chirp from kHz to kHz over second has kHz/s², resulting in a frequency that starts slowly and accelerates toward the end.[3]Exponential Chirp

An exponential chirp is a time-varying signal characterized by an instantaneous frequency that increases or decreases multiplicatively over time. The instantaneous frequency is given bywhere is the initial frequency at , and for an up-chirp (increasing frequency) or for a down-chirp. This formulation ensures exponential growth or decay in frequency, contrasting with additive changes in other chirp types. The phase of the exponential chirp is derived by integrating the instantaneous angular frequency from 0 to :

The resulting signal form is

where is the constant amplitude and is an optional initial phase offset (often set to 0). This phase structure arises directly from the exponential frequency profile, leading to a nonlinear accumulation of oscillations that accelerates with time for up-chirps. Key properties of the exponential chirp include a linear frequency progression when plotted on a logarithmic scale versus time, which yields a constant relative bandwidth . This constant relative rate makes it ideal for applications requiring uniform coverage across multiplicative frequency ranges, such as octave-spanning signals where the sweep rate can be specified in octaves per second. For instance, the logarithmic nature ensures equal time allocation per octave, unlike linear chirps that devote more time to higher frequencies.[19] As a representative example, consider generating an exponential chirp sweeping from 100 Hz to 10 kHz over 1 second. Here, Hz, the final frequency Hz at s, so . Equivalently, with , spanning approximately 6.64 octaves at a rate of 6.64 octaves per second. This setup produces a signal with rapidly increasing perceived pitch, emphasizing the logarithmic scaling.[20]

Hyperbolic Chirp

A hyperbolic chirp is a frequency-modulated signal characterized by an instantaneous frequency that decreases hyperbolically with time, following an inverse relationship that results in a decaying sweep rate approaching zero. The frequency function is defined as , where is the starting frequency at , and is the chirp rate parameter with units of inverse time. This form ensures the frequency remains positive and bounded below by zero while starting at .[21] The phase of the hyperbolic chirp is derived from the integral of the instantaneous frequency: This logarithmic phase accumulation reflects the cumulative effect of the inversely varying frequency. The corresponding signal equation for a real-valued cosine-modulated hyperbolic chirp is then where is the constant amplitude, typically assuming and the signal windowed to a finite duration in practice.[21] Key properties of the hyperbolic chirp include its frequency asymptoting to zero as , which inherently bounds the spectral content from below and prevents unbounded frequency excursions. This structure makes it advantageous for modeling scenarios involving Doppler effects, as the waveform exhibits invariance to Doppler scaling, preserving matched filter performance under velocity-induced shifts. Additionally, the bounded frequency trajectory contributes to controlled spectral occupancy, aiding in applications requiring spectra confined within specific limits.[21][22] A representative example is a hyperbolic chirp starting at kHz and decreasing to 500 Hz over 0.1 seconds, requiring s to achieve the desired endpoint frequency via Hz. In limited regimes, such as small , this form can approximate aspects of an exponential chirp.[21]Generation

Analytical Generation

Analytical generation of chirp signals relies on deriving the phase function through direct integration of the specified instantaneous frequency profile, providing closed-form expressions under ideal mathematical conditions. The instantaneous frequency defines the time-varying frequency content, and the phase is obtained via , assuming a starting time of for simplicity. The resulting chirp signal is then expressed as , where is the amplitude and is an initial phase offset, typically set to zero. This integration approach ensures the signal's frequency evolves precisely as prescribed, forming the theoretical foundation for chirp design in signal processing.[23] For standard chirp types, closed-form solutions for the phase emerge from evaluating the integral explicitly. In the case of a linear chirp, where with initial frequency and chirp rate , the phase simplifies to a quadratic form: This quadratic phase directly yields the familiar linear frequency sweep over time . For exponential and hyperbolic chirps, the instantaneous frequency follows or , respectively, leading to logarithmic phase expressions: for the hyperbolic case, which provides a frequency decrease approaching zero asymptotically. These analytical solutions facilitate precise theoretical modeling without numerical computation.[24] Asymptotic analysis of chirp envelopes and spectra often employs the stationary phase approximation (SPA), which approximates integrals of the form by identifying points where the phase derivative vanishes, i.e., stationary points. For chirp signals, SPA reveals the envelope's behavior in the frequency domain, approximating the magnitude spectrum as at the stationary time where , with the second derivative of the phase. This method is particularly useful for high-frequency or large time-bandwidth products, providing insight into sidelobe structures and resolution limits without full Fourier computation. However, SPA's accuracy diminishes for low-frequency components or near boundaries.[24] Normalization techniques ensure consistent signal properties across analyses, typically scaling for unit energy or constant amplitude. For unit energy, the signal is divided by its root-mean-square value, such that , which for a finite-duration chirp of length approximates to under constant amplitude assumptions. Constant amplitude normalization sets , preserving the envelope shape while focusing on phase modulation. These methods standardize comparisons in theoretical studies, though exact normalization factors depend on the chirp parameters.[25] Analytical forms assume ideal conditions, such as infinite precision in frequency definition and absence of noise or nonlinearities, which ignore real-world distortions like amplifier saturation or dispersion in transmission media. This idealization supports foundational derivations but requires validation against practical implementations for applied scenarios.[26]Practical Generation

Practical generation of chirp signals involves computational and physical methods to approximate the ideal analytical forms, enabling real-time implementation in various systems. Digital synthesis techniques, such as direct digital synthesizers (DDS), utilize phase accumulators to generate chirp signals by incrementally updating the phase based on a time-varying frequency profile. In a DDS architecture, the phase accumulator adds a frequency tuning word at each clock cycle, producing a phase that increases nonlinearly for chirps, which is then converted to amplitude via a sine lookup table or CORDIC algorithm before digital-to-analog conversion. This approach allows for flexible, high-resolution frequency sweeps in applications requiring precise control, such as radar systems.[27][28] Numerical methods for chirp generation rely on discrete-time approximations through sampling of the continuous waveform. A common implementation computes the signal as , where represents the instantaneous frequency at sample , and is the sampling interval, effectively discretizing the phase accumulation process. This summation mirrors the integral in analytical forms but is performed iteratively in software or hardware for finite sample lengths, ensuring the signal remains bandlimited within the Nyquist criterion. Such methods are foundational in digital signal processing for generating chirps without dedicated hardware.[27] Hardware approaches for analog chirp production often employ voltage-controlled oscillators (VCOs) driven by linear voltage ramps to sweep the frequency. A VCO's output frequency varies proportionally with the input control voltage; applying a ramp signal to this input produces a linear chirp, where the ramp's slope determines the chirp rate. This technique is prevalent in analog RF systems for its simplicity, though it requires compensation for VCO nonlinearities to maintain linearity across the sweep.[29] Software tools facilitate chirp generation in simulation and prototyping environments. In Python, the SciPy library'sscipy.signal.chirp function generates a swept-frequency signal specified by initial frequency , end time , final frequency , and method (e.g., 'linear' or 'quadratic'), returning a discrete array evaluated at given times. Similarly, MATLAB's chirp function produces samples of a linear or exponential swept cosine at specified times, with parameters for start/end frequencies and optional phase. These functions implement the discrete approximations internally, supporting rapid development and analysis.[20][3]

Implementation challenges in practical chirp generation include managing quantization noise from finite-bit phase accumulators and digital-to-analog converters in DDS systems, which introduces spurs and degrades signal purity, with signal-to-quantization-noise ratio scaling as dB for -bit resolution. Aliasing must be prevented by oversampling the chirp signal, particularly for wideband sweeps where the highest frequency approaches the sampling rate, requiring rates at least twice the maximum instantaneous frequency to avoid spectral folding. Additionally, RF systems face bandwidth limitations due to VCO tuning ranges and component parasitics, often restricting relative bandwidths to under 100% without advanced architectures like multi-stage PLLs.[27][30]