Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Matched filter

View on WikipediaIn signal processing, the output of the matched filter is given by correlating a known delayed signal, or template, with an unknown signal to detect the presence of the template in the unknown signal.[1][2] This is equivalent to convolving the unknown signal with a conjugated time-reversed version of the template. The matched filter is the optimal linear filter for maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the presence of additive stochastic noise.

Matched filters are commonly used in radar, in which a known signal is sent out, and the reflected signal is examined for common elements of the out-going signal. Pulse compression is an example of matched filtering. It is so called because the impulse response is matched to input pulse signals. Two-dimensional matched filters are commonly used in image processing, e.g., to improve the SNR of X-ray observations. Additional applications of note are in seismology and gravitational-wave astronomy.

Matched filtering is a demodulation technique with LTI (linear time invariant) filters to maximize SNR.[3] It was originally also known as a North filter.[4]

Derivation

[edit]Derivation via matrix algebra

[edit]The following section derives the matched filter for a discrete-time system. The derivation for a continuous-time system is similar, with summations replaced with integrals.

The matched filter is the linear filter, , that maximizes the output signal-to-noise ratio.

where is the input as a function of the independent variable , and is the filtered output. Though we most often express filters as the impulse response of convolution systems, as above (see LTI system theory), it is easiest to think of the matched filter in the context of the inner product, which we will see shortly.

We can derive the linear filter that maximizes output signal-to-noise ratio by invoking a geometric argument. The intuition behind the matched filter relies on correlating the received signal (a vector) with a filter (another vector) that is parallel with the signal, maximizing the inner product. This enhances the signal. When we consider the additive stochastic noise, we have the additional challenge of minimizing the output due to noise by choosing a filter that is orthogonal to the noise.

Let us formally define the problem. We seek a filter, , such that we maximize the output signal-to-noise ratio, where the output is the inner product of the filter and the observed signal .

Our observed signal consists of the desirable signal and additive noise :

Let us define the auto-correlation matrix of the noise, reminding ourselves that this matrix has Hermitian symmetry, a property that will become useful in the derivation:

where denotes the conjugate transpose of , and denotes expectation (note that in case the noise has zero-mean, its auto-correlation matrix is equal to its covariance matrix).

Let us call our output, , the inner product of our filter and the observed signal such that

We now define the signal-to-noise ratio, which is our objective function, to be the ratio of the power of the output due to the desired signal to the power of the output due to the noise:

We rewrite the above:

We wish to maximize this quantity by choosing . Expanding the denominator of our objective function, we have

Now, our becomes

We will rewrite this expression with some matrix manipulation. The reason for this seemingly counterproductive measure will become evident shortly. Exploiting the Hermitian symmetry of the auto-correlation matrix , we can write

We would like to find an upper bound on this expression. To do so, we first recognize a form of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality:

which is to say that the square of the inner product of two vectors can only be as large as the product of the individual inner products of the vectors. This concept returns to the intuition behind the matched filter: this upper bound is achieved when the two vectors and are parallel. We resume our derivation by expressing the upper bound on our in light of the geometric inequality above:

Our valiant matrix manipulation has now paid off. We see that the expression for our upper bound can be greatly simplified:

We can achieve this upper bound if we choose,

where is an arbitrary real number. To verify this, we plug into our expression for the output :

Thus, our optimal matched filter is

We often choose to normalize the expected value of the power of the filter output due to the noise to unity. That is, we constrain

This constraint implies a value of , for which we can solve:

yielding

giving us our normalized filter,

If we care to write the impulse response of the filter for the convolution system, it is simply the complex conjugate time reversal of the input .

Though we have derived the matched filter in discrete time, we can extend the concept to continuous-time systems if we replace with the continuous-time autocorrelation function of the noise, assuming a continuous signal , continuous noise , and a continuous filter .

Derivation via Lagrangian

[edit]Alternatively, we may solve for the matched filter by solving our maximization problem with a Lagrangian. Again, the matched filter endeavors to maximize the output signal-to-noise ratio () of a filtered deterministic signal in stochastic additive noise. The observed sequence, again, is

with the noise auto-correlation matrix,

The signal-to-noise ratio is

where and .

Evaluating the expression in the numerator, we have

and in the denominator,

The signal-to-noise ratio becomes

If we now constrain the denominator to be 1, the problem of maximizing is reduced to maximizing the numerator. We can then formulate the problem using a Lagrange multiplier:

which we recognize as a generalized eigenvalue problem

Since is of unit rank, it has only one nonzero eigenvalue. It can be shown that this eigenvalue equals

yielding the following optimal matched filter

This is the same result found in the previous subsection.

Interpretation as a least-squares estimator

[edit]Derivation

[edit]Matched filtering can also be interpreted as a least-squares estimator for the optimal location and scaling of a given model or template. Once again, let the observed sequence be defined as

where is uncorrelated zero mean noise. The signal is assumed to be a scaled and shifted version of a known model sequence :

We want to find optimal estimates and for the unknown shift and scaling by minimizing the least-squares residual between the observed sequence and a "probing sequence" :

The appropriate will later turn out to be the matched filter, but is as yet unspecified. Expanding and the square within the sum yields

The first term in brackets is a constant (since the observed signal is given) and has no influence on the optimal solution. The last term has constant expected value because the noise is uncorrelated and has zero mean. We can therefore drop both terms from the optimization. After reversing the sign, we obtain the equivalent optimization problem

Setting the derivative w.r.t. to zero gives an analytic solution for :

Inserting this into our objective function yields a reduced maximization problem for just :

The numerator can be upper-bounded by means of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality:

The optimization problem assumes its maximum when equality holds in this expression. According to the properties of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, this is only possible when

for arbitrary non-zero constants or , and the optimal solution is obtained at as desired. Thus, our "probing sequence" must be proportional to the signal model , and the convenient choice yields the matched filter

Note that the filter is the mirrored signal model. This ensures that the operation to be applied in order to find the optimum is indeed the convolution between the observed sequence and the matched filter . The filtered sequence assumes its maximum at the position where the observed sequence best matches (in a least-squares sense) the signal model .

Implications

[edit]The matched filter may be derived in a variety of ways,[2] but as a special case of a least-squares procedure it may also be interpreted as a maximum likelihood method in the context of a (coloured) Gaussian noise model and the associated Whittle likelihood.[5] If the transmitted signal possessed no unknown parameters (like time-of-arrival, amplitude,...), then the matched filter would, according to the Neyman–Pearson lemma, minimize the error probability. However, since the exact signal generally is determined by unknown parameters that effectively are estimated (or fitted) in the filtering process, the matched filter constitutes a generalized maximum likelihood (test-) statistic.[6] The filtered time series may then be interpreted as (proportional to) the profile likelihood, the maximized conditional likelihood as a function of the ("arrival") time parameter.[7] This implies in particular that the error probability (in the sense of Neyman and Pearson, i.e., concerning maximization of the detection probability for a given false-alarm probability[8]) is not necessarily optimal. What is commonly referred to as the Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is supposed to be maximized by a matched filter, in this context corresponds to , where is the (conditionally) maximized likelihood ratio.[7] [nb 1]

The construction of the matched filter is based on a known noise spectrum. In practice, however, the noise spectrum is usually estimated from data and hence only known up to a limited precision. For the case of an uncertain spectrum, the matched filter may be generalized to a more robust iterative procedure with favourable properties also in non-Gaussian noise.[7]

Frequency-domain interpretation

[edit]When viewed in the frequency domain, it is evident that the matched filter applies the greatest weighting to spectral components exhibiting the greatest signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., large weight where noise is relatively low, and vice versa). In general this requires a non-flat frequency response, but the associated "distortion" is no cause for concern in situations such as radar and digital communications, where the original waveform is known and the objective is the detection of this signal against the background noise. On the technical side, the matched filter is a weighted least-squares method based on the (heteroscedastic) frequency-domain data (where the "weights" are determined via the noise spectrum, see also previous section), or equivalently, a least-squares method applied to the whitened data.

Examples

[edit]Radar and sonar

[edit]Matched filters are often used in signal detection.[1] As an example, suppose that we wish to judge the distance of an object by reflecting a signal off it. We may choose to transmit a pure-tone sinusoid at 1 Hz. We assume that our received signal is an attenuated and phase-shifted form of the transmitted signal with added noise.

To judge the distance of the object, we correlate the received signal with a matched filter, which, in the case of white (uncorrelated) noise, is another pure-tone 1-Hz sinusoid. When the output of the matched filter system exceeds a certain threshold, we conclude with high probability that the received signal has been reflected off the object. Using the speed of propagation and the time that we first observe the reflected signal, we can estimate the distance of the object. If we change the shape of the pulse in a specially designed way, the signal-to-noise ratio and the distance resolution can be even improved after matched filtering: this is a technique known as pulse compression.

Additionally, matched filters can be used in parameter estimation problems (see estimation theory). To return to our previous example, we may desire to estimate the speed of the object, in addition to its position. To exploit the Doppler effect, we would like to estimate the frequency of the received signal. To do so, we may correlate the received signal with several matched filters of sinusoids at varying frequencies. The matched filter with the highest output will reveal, with high probability, the frequency of the reflected signal and help us determine the radial velocity of the object, i.e. the relative speed either directly towards or away from the observer. This method is, in fact, a simple version of the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). The DFT takes an -valued complex input and correlates it with matched filters, corresponding to complex exponentials at different frequencies, to yield complex-valued numbers corresponding to the relative amplitudes and phases of the sinusoidal components (see Moving target indication).

Digital communications

[edit]The matched filter is also used in communications. In the context of a communication system that sends binary messages from the transmitter to the receiver across a noisy channel, a matched filter can be used to detect the transmitted pulses in the noisy received signal.

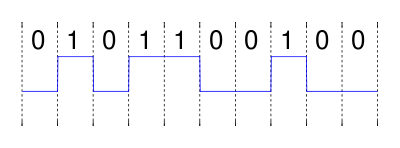

Imagine we want to send the sequence "0101100100" coded in non polar non-return-to-zero (NRZ) through a certain channel.

Mathematically, a sequence in NRZ code can be described as a sequence of unit pulses or shifted rect functions, each pulse being weighted by +1 if the bit is "1" and by -1 if the bit is "0". Formally, the scaling factor for the bit is,

We can represent our message, , as the sum of shifted unit pulses:

where is the time length of one bit and is the rectangular function.

Thus, the signal to be sent by the transmitter is

If we model our noisy channel as an AWGN channel, white Gaussian noise is added to the signal. At the receiver end, for a Signal-to-noise ratio of 3 dB, this may look like:

A first glance will not reveal the original transmitted sequence. There is a high power of noise relative to the power of the desired signal (i.e., there is a low signal-to-noise ratio). If the receiver were to sample this signal at the correct moments, the resulting binary message could be incorrect.

To increase our signal-to-noise ratio, we pass the received signal through a matched filter. In this case, the filter should be matched to an NRZ pulse (equivalent to a "1" coded in NRZ code). Precisely, the impulse response of the ideal matched filter, assuming white (uncorrelated) noise should be a time-reversed complex-conjugated scaled version of the signal that we are seeking. We choose

In this case, due to symmetry, the time-reversed complex conjugate of is in fact , allowing us to call the impulse response of our matched filter convolution system.

After convolving with the correct matched filter, the resulting signal, is,

where denotes convolution.

Which can now be safely sampled by the receiver at the correct sampling instants, and compared to an appropriate threshold, resulting in a correct interpretation of the binary message.

Gravitational-wave astronomy

[edit]Matched filters play a central role in gravitational-wave astronomy.[9] The first observation of gravitational waves was based on large-scale filtering of each detector's output for signals resembling the expected shape, followed by subsequent screening for coincident and coherent triggers between both instruments.[10] False-alarm rates, and with that, the statistical significance of the detection were then assessed using resampling methods.[11][12] Inference on the astrophysical source parameters was completed using Bayesian methods based on parameterized theoretical models for the signal waveform and (again) on the Whittle likelihood.[13][14]

Seismology

[edit]Matched filters find use in seismology to detect similar earthquake or other seismic signals, often using multicomponent and/or multichannel empirically determined templates.[15] Matched filtering applications in seismology include the generation of large event catalogues to study earthquake seismicity [16] and volcanic activity,[17][18] and in the global detection of nuclear explosions.[19]

Biology

[edit]Animals living in relatively static environments would have relatively fixed features of the environment to perceive. This allows the evolution of filters that match the expected signal with the highest signal-to-noise ratio, the matched filter.[20] Sensors that perceive the world "through such a 'matched filter' severely limits the amount of information the brain can pick up from the outside world, but it frees the brain from the need to perform more intricate computations to extract the information finally needed for fulfilling a particular task."[21]

See also

[edit]- Periodogram

- Filtered backprojection (Radon transform)

- Digital filter

- Statistical signal processing

- Whittle likelihood

- Profile likelihood

- Detection theory

- Multiple comparisons problem

- Channel capacity

- Noisy-channel coding theorem

- Spectral density estimation

- Least mean squares (LMS) filter

- Wiener filter

- MUltiple SIgnal Classification (MUSIC), a popular parametric superresolution method

- SAMV

Notes

[edit]- ^ The common reference to SNR has in fact been criticized as somewhat misleading: "The interesting feature of this approach is that theoretical perfection is attained without aiming consciously at a maximum signal/noise ratio. As the matter of quite incidental interest, it happens that the operation [...] does maximize the peak signal/noise ratio, but this fact plays no part whatsoever in the present theory. Signal/noise ratio is not a measure of information [...]." (Woodward, 1953;[1] Sec.5.1).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Woodward, P. M. (1953). Probability and information theory with applications to radar. London: Pergamon Press.

- ^ a b Turin, G. L. (1960). "An introduction to matched filters". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 6 (3): 311–329. doi:10.1109/TIT.1960.1057571. S2CID 5128742.

- ^ "Demodulation". OpenStax CNX. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- ^ After D.O. North who was among the first to introduce the concept: North, D. O. (1943). "An analysis of the factors which determine signal/noise discrimination in pulsed carrier systems". Report PPR-6C, RCA Laboratories, Princeton, NJ.

Re-print: North, D. O. (1963). "An analysis of the factors which determine signal/noise discrimination in pulsed-carrier systems". Proceedings of the IEEE. 51 (7): 1016–1027. doi:10.1109/PROC.1963.2383.

See also: Jaynes, E. T. (2003). "14.6.1 The classical matched filter". Probability theory: The logic of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - ^ Choudhuri, N.; Ghosal, S.; Roy, A. (2004). "Contiguity of the Whittle measure for a Gaussian time series". Biometrika. 91 (4): 211–218. doi:10.1093/biomet/91.1.211.

- ^ Mood, A. M.; Graybill, F. A.; Boes, D. C. (1974). "IX. Tests of hypotheses". Introduction to the theory of statistics (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b c Röver, C. (2011). "Student-t based filter for robust signal detection". Physical Review D. 84 (12) 122004. arXiv:1109.0442. Bibcode:2011PhRvD..84l2004R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.84.122004.

- ^ Neyman, J.; Pearson, E. S. (1933). "On the problem of the most efficient tests of statistical hypotheses". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A. 231 (694–706): 289–337. Bibcode:1933RSPTA.231..289N. doi:10.1098/rsta.1933.0009.

- ^ Schutz, B. F. (1999). "Gravitational wave astronomy". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 16 (12A): A131 – A156. arXiv:gr-qc/9911034. Bibcode:1999CQGra..16A.131S. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/16/12A/307. S2CID 19021009.

- ^ "LIGO: How We Searched For Merging Black Holes And Found GW150914".

A technique known as matched filtering is used to see if there are any signals contained within our data. The aim of matched filtering is to see if the data contains any signals similar to a template bank member. Since our templates should describe the gravitational waveforms for the range of different merging systems that we expect to be able to see, any sufficiently loud signal should be found by this method.

- ^ Usman, Samantha A. (2016). "The PyCBC search for gravitational waves from compact binary coalescence". Class. Quantum Grav. 33 (21) 215004. arXiv:1508.02357. Bibcode:2016CQGra..33u5004U. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/33/21/215004. S2CID 53979477.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (The LIGO Scientific Collaboration, the Virgo Collaboration) (2016). "GW150914: First results from the search for binary black hole coalescence with Advanced LIGO". Physical Review D. 93 (12) 122003. arXiv:1602.03839. Bibcode:2016PhRvD..93l2003A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.93.122003. PMC 7430253. PMID 32818163.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (The LIGO Scientific Collaboration, the Virgo Collaboration) (2016). "Properties of the binary black hole merger GW150914". Physical Review Letters. 116 (24) 241102. arXiv:1602.03840. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116x1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.241102. PMID 27367378. S2CID 217406416.

- ^ Meyer, R.; Christensen, N. (2016). "Gravitational waves: A statistical autopsy of a black hole merger". Significance. 13 (2): 20–25. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2016.00896.x.

- ^ Senobari, N.; Funning, G.; Keogh, E.; Zhu, Y.; Yah, C; Zimmerman, Z.; Mueen, A. (2018). "Super-Efficient Cross-Correlation (SEC-C): A Fast Matched Filtering Code Suitable for Desktop Computers". Seismological Research Letters. 90 (1).

- ^ Shelly, D. (2017). "A 15 year catalog of more than 1 million low-frequency earthquakes: Tracking tremor and slip along the deep San Andreas Fault". Journal of Geophysical Research. 122 (5): 3739. Bibcode:2017JGRB..122.3739S. doi:10.1002/2017JB014047.

- ^ Shelly, D.; Thelen, W. (2019). "Anatomy of a Caldera Collapse: Kilauea 2018 Summit Seismicity Sequence in High Resolution". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (24): 14395–14403. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..4614395S. doi:10.1029/2019GL085636.

- ^ Knox, H.; Chaput, J.; Aster, R.; Kyle, P. (2018). "Multi-year shallow conduit changes observed with lava lake eruption seismograms at Erebus volcano, Antarctica". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 123 (4): 3178. Bibcode:2018JGRB..123.3178K. doi:10.1002/2017JB015045.

- ^ Robinson, E. (1963). "Mathematical development of discrete filters for the detection of nuclear explosions". Journal of Geophysical Research. 68 (19): 5559. Bibcode:1963JGR....68.5559R. doi:10.1029/JZ068i019p05559.

- ^ Warrant, Eric J. (October 2016). "Sensory matched filters". Current Biology. 26 (20): R976 – R980. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.R976W. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.042. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 27780072.

- ^ Wehner, Rüdiger (1987). "'Matched filters': neural models of the external world". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 161 (4): 511–531. doi:10.1007/bf00603659. ISSN 0340-7594. S2CID 32779686.

Further reading

[edit]- Turin, G. L. (1960). "An introduction to matched filters". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 6 (3): 311–329. doi:10.1109/TIT.1960.1057571. S2CID 5128742.

- Wainstein, L. A.; Zubakov, V. D. (1962). Extraction of signals from noise. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Melvin, W. L. (2004). "A STAP overview". IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine. 19 (1): 19–35. Bibcode:2004IAESM..19a..19M. doi:10.1109/MAES.2004.1263229. S2CID 31133715.

- Röver, C. (2011). "Student-t based filter for robust signal detection". Physical Review D. 84 (12) 122004. arXiv:1109.0442. Bibcode:2011PhRvD..84l2004R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.84.122004.

- Fish, A.; Gurevich, S.; Hadani, R.; Sayeed, A.; Schwartz, O. (December 2011). "Computing the matched filter in linear time". arXiv:1112.4883 [cs.IT].

Matched filter

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

A matched filter is a linear time-invariant filter specifically designed to maximize the output signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) when detecting a known deterministic signal embedded in additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). This optimization occurs by tailoring the filter's impulse response to the shape of the expected signal, ensuring that the filter's output peaks at the moment the signal is present, thereby facilitating reliable detection in noisy conditions.[5] The primary purpose of the matched filter is to enhance the detectability of predetermined signals, such as radar pulses or communication waveforms, within environments corrupted by noise, where direct observation might otherwise fail. By achieving the theoretical maximum SNR for linear filters under AWGN assumptions, it provides an optimal trade-off between signal amplification and noise suppression, making it indispensable for applications requiring high detection probability with minimal false alarms. This approach assumes the noise is additive, stationary, and Gaussian with a flat power spectral density, without which the optimality guarantee does not hold.[5][3] At its core, the matched filter operates on the principle of correlation: it effectively "matches" the received waveform against the known signal template, aligning and reinforcing the desired signal energy while the uncorrelated noise averages out. This intuitive matching process boosts the signal's prominence relative to the noise floor, enabling the filter to extract weak signals that would be obscured in unprocessed data.[5]Signal and Noise Model

The received signal in the context of matched filtering is modeled as , where represents a known deterministic signal of finite duration, typically from to , and denotes stationary random noise.[6] This additive model assumes the noise corrupts the signal linearly without altering its form. The noise is characterized as additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), which is zero-mean and stationary, with a constant two-sided power spectral density of .[6] Its autocorrelation function is given by , reflecting the uncorrelated nature of the noise samples at distinct times.[6] The detection problem framed by this model involves binary hypothesis testing: under the null hypothesis , only noise is present (); under the alternative , the signal is present ().[6] Alternatively, it supports parameter estimation, such as determining the signal's amplitude, delay, or phase. The key performance metric is the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) evaluated at the sampling instant , the end of the signal duration, which quantifies detection reliability.[6] In discrete-time formulations, suitable for sampled systems, the model becomes for , where is the sampled signal and are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) zero-mean Gaussian random variables with variance .[7] This analog preserves the additive structure and noise statistics, facilitating digital implementation while aligning with the continuous-time SNR maximization goal at the final sample.[7]Historical Context

Origins in Radar

The matched filter emerged during World War II as a critical advancement in radar signal processing, driven by the urgent need to enhance detection capabilities amid wartime demands for reliable anti-aircraft defense systems. At RCA Laboratories in Princeton, New Jersey, researchers focused on improving the performance of radar receivers to distinguish faint echo pulses from pervasive noise, a challenge intensified by the high-stakes requirements of tracking incoming threats. This work was part of broader U.S. efforts to bolster radar technology, where RCA contributed significantly to military electronics development during the conflict.[8] The concept was first formally introduced by D. O. North in his 1943 technical report, "An Analysis of the Factors Which Determine Signal/Noise Discrimination in Pulsed-Carrier Systems," prepared as RCA Laboratories Report PTR-6C. In this seminal document, North analyzed the effects of noise on radar pulse detection and derived the optimal filter structure for maximizing signal-to-noise ratio in additive noise environments, laying the theoretical groundwork for what would become known as the matched filter. North's analysis emphasized the filter's role in processing known radar waveforms to achieve superior discrimination, particularly for pulsed signals used in early radar systems. The report, initially classified due to its military relevance, was later reprinted in the Proceedings of the IEEE in 1963.[9] North is credited with coining the term "matched filter," reflecting its design as a filter precisely tailored—or "matched"—to the expected signal shape, initially referred to in some contexts as a "North filter." Early applications centered on radar pulse compression techniques, which compressed transmitted wide pulses into narrow received ones to improve range resolution without sacrificing detection range, a vital feature for anti-aircraft radars operating in noisy conditions. These implementations predated digital computing era, relying entirely on analog circuits such as delay lines and tuned amplifiers to realize the filter in hardware.[10]Key Developments and Contributors

The matched filter theory advanced significantly in the post-World War II era through its integration with emerging information theory. Claude Shannon's work on communication in the presence of noise (1949) provided theoretical foundations in information theory that reinforced the optimality of structures like the matched filter for detection in Gaussian noise, linking it to the sampling theorem for bandlimited signals and setting foundational limits on reliable communication. This work bridged radar detection principles with broader communication systems, influencing subsequent theoretical developments in the 1950s. Key contributors at the MIT Radiation Laboratory during the late 1940s and early 1950s, including researchers like John L. Hancock, refined practical aspects of matched filter design for radar receivers, as documented in the laboratory's comprehensive technical series.[11] Peter M. Woodward further formalized the matched filter's role in SNR maximization for radar applications in his 1953 monograph, drawing on Shannon's ideas to emphasize its optimality in probabilistic detection scenarios. In 1960, G. L. Turin published a seminal tutorial on matched filters, emphasizing their role in correlation and signal coding techniques, particularly for radar applications.[12] Milestones in the 1960s included the formulation of discrete-time matched filters, enabling implementation in early digital signal processing systems for sampled data.[13] These advancements were consolidated in textbooks by the 1970s, marking the last major theoretical refinements, while practical implementations evolved rapidly with digital signal processors, improving real-time applications in radar and communications.Derivation

Time-Domain Derivation

The received signal is modeled as , where is the known deterministic signal of finite duration and is zero-mean additive white Gaussian noise with two-sided power spectral density . The output of a linear time-invariant filter with impulse response is the convolution . The filter output is sampled at , giving .[14] The expected value of the output is , since . The variance, under the white noise assumption, is . The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at the sampling instant is thus To maximize the SNR, it suffices to maximize the squared correlation term in the numerator subject to a unit energy constraint on the filter, . Make the change of integration variable in the numerator to obtain . The optimization problem is therefore to maximize the functional subject to .[14] This is an isoperimetric problem in the calculus of variations. Form the augmented functional where is the Lagrange multiplier enforcing the constraint. Since the integrand does not depend on derivatives of , the Euler-Lagrange equation reduces to the algebraic condition obtained by setting the functional derivative with respect to to zero: .[15] Solving for yields , or equivalently , where the scaling constant is chosen to satisfy the unit energy constraint. Assuming for , the impulse response of the matched filter is This result demonstrates that maximum SNR is achieved when the filter impulse response is a scaled, time-reversed version of the known signal, centered at the sampling time .Matrix Algebra Formulation

In the discrete-time formulation, the received signal is represented as a vector , where and are -dimensional vectors, is an unknown scalar amplitude (often normalized to 1 for derivation purposes), and is a zero-mean Gaussian noise vector with covariance matrix .[16] The output of a linear filter with weight vector is . To derive the optimal filter, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at the output is maximized, defined as .[16] Since is a constant scalar, the maximization reduces to extremizing the Rayleigh quotient . The solution to this optimization problem, obtained via the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality or the generalized eigenvalue equation , yields .[16] For normalization such that the filter has unit gain or the denominator is 1, the weights are given by , where denotes the Euclidean norm.[16] In the special case of white noise, where and is the noise variance, the expression simplifies to , so the vector form computes the correlation . For causal FIR filter implementation on streaming data, the coefficients are the time-reversed , i.e., (real signals), corresponding to the discrete convolution evaluated at , which equals when the signal aligns from index 0 to .[16] This matrix formulation reveals that the matched filter weights form the principal eigenvector of , where is the rank-one outer product matrix representing the deterministic signal.[16] This perspective extends naturally to colored noise scenarios by pre-whitening the signal and noise through , reducing the problem to the white-noise case.[16]Interpretations

Least-Squares Estimator

The matched filter can be interpreted as the optimal linear estimator for the amplitude of a known signal embedded in additive white Gaussian noise , where the received signal is modeled as . In this framework, the filter output serves as an estimate of , with the filter coefficients selected to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) . This approach yields the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) under the Gauss-Markov theorem for uncorrelated noise, providing both unbiasedness and minimum variance among linear estimators. To derive this, consider the MSE expression: . Differentiating with respect to and setting the result to zero gives the normal equations: . For white noise with covariance , and given , the solution simplifies to . This weight vector corresponds to the time-reversed signal in continuous time, normalized appropriately, ensuring the estimator aligns the received signal with the known waveform to minimize estimation error. In continuous-time form, the estimator is , where is the signal energy. This correlation-based output, sampled at the appropriate time, directly estimates . The estimator is unbiased, as , since the noise term averages to zero under the integral. Furthermore, the variance is minimized among all linear unbiased estimators, highlighting the matched filter's efficiency in amplitude recovery.Frequency-Domain Perspective

The frequency-domain perspective on the matched filter emphasizes its role in aligning the filter's response with the signal's spectrum while accounting for the noise power spectral density (PSD). In this view, the matched filter operates by multiplying the received signal's Fourier transform with the filter's transfer function, effectively weighting frequency components to maximize the output signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at a specified time . For additive noise with PSD , the transfer function is given by where denotes the Fourier transform of the known signal , and the asterisk indicates complex conjugation.[17] This form ensures that the filter's magnitude is proportional to , boosting signal-dominant frequencies while suppressing those dominated by noise. For white noise, where is constant (with the single-sided noise PSD), the transfer function simplifies to , directly matching the signal's spectrum in magnitude and compensating for phase.[18] The optimality of this transfer function arises from maximizing the SNR in the frequency domain. The output signal amplitude at time is , while the noise variance is . The instantaneous SNR is then Applying the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality yields the maximum SNR when , resulting in For white noise, this reduces to , where is the signal energy.[19] This derivation highlights the filter's spectral matching property: it shapes the response to emphasize frequencies where the signal-to-noise ratio is high, effectively whitening the noise before correlation.[20] Parseval's theorem provides a bridge between this frequency-domain formulation and the time-domain correlation interpretation, equating the energy of the filter output to the integral of the product of the signal and filter power spectra. Specifically, the squared magnitude of the output at the peak equals (up to scaling), which aligns with the time-domain inner product .[21] The linear phase term in ensures causality and shifts the output peak to exactly , aligning the maximum response with the expected signal arrival without distorting the waveform shape.[22] This phase alignment is crucial for applications requiring precise timing, such as pulse detection in radar systems.Properties and Optimality

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Maximization

The matched filter achieves the theoretical maximum signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for detecting a known deterministic signal in additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), a result first established in the context of radar signal processing. For a signal with finite energy , corrupted by AWGN with two-sided power spectral density , the maximum achievable output SNR at the optimal sampling instant is .[18] This bound represents the fundamental limit for linear time-invariant filters under these conditions, quantifying the filter's performance in terms of the signal's total energy relative to the noise density.[23] The proof of this optimality relies on the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality applied to the inner product defined by the signal and filter responses. Specifically, the output signal power is maximized when the filter impulse response is proportional to the time-reversed signal, yielding an output SNR of , where and are the Fourier transforms of the signal and filter, respectively; equality holds only for the matched case , simplifying to .[18] Any other linear filter produces a strictly lower SNR, as deviations from the matched form reduce the numerator relative to the denominator in the inequality.[23] This result extends to colored Gaussian noise, where the noise power spectral density is non-flat, by first applying a pre-whitening filter to transform the noise into white form before matched filtering; the maximum SNR then follows the same bound, with adjusted for the whitened noise variance.[24]Response Characteristics

When the matched filter receives its matched input signal , assuming the filter impulse response is for some delay , the signal component of the output is . This expression represents the signal's autocorrelation function , where .[3] The autocorrelation peaks sharply at with amplitude equal to the signal energy , concentrating the signal power at the expected arrival time.[3] For additive white Gaussian noise at the input with two-sided power spectral density (PSD) , the noise at the matched filter output becomes colored, with PSD given by , where is the Fourier transform of .[25] This shaping of the noise spectrum mirrors the signal's frequency content, resulting in correlated noise samples across time that reflect the filter's bandwidth limitations.[25] The sidelobe structure in the signal response arises from the shape of the autocorrelation function and varies with the input signal design; for instance, linear frequency-modulated (chirp) signals produce outputs with notably low sidelobe levels relative to the main peak, enhancing detectability in cluttered environments.[26] In scenarios involving Doppler shifts, the matched filter's response extends to the ambiguity function, a two-dimensional surface that quantifies resolution in both time delay and frequency offset.[27] Detection using the matched filter typically involves evaluating the output against a predefined threshold calibrated to the output noise variance, where exceedance indicates signal presence with controlled false alarm rates.[3]Implementations

Continuous-Time Realization

In continuous-time systems, matched filters are realized using analog hardware to process signals in real time without sampling, implementing an impulse response , where is the known signal waveform, is a suitable delay to ensure causality, and * denotes complex conjugation.[28] Common analog methods include delay lines, surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices, and lumped-element circuits, which replicate this time-reversed and conjugated signal shape through physical propagation or reactive components.[29][30] A prevalent design approach employs transversal filters, consisting of a delay line with multiple taps whose outputs are weighted by coefficients proportional to and summed, effectively convolving the input with the matched response. For a rectangular pulse of duration and amplitude , the transversal filter uses uniform weights across taps spaced by the line's delay per section, yielding a simple integrator-like output that peaks sharply upon signal match.[28] These structures, often built on SAW substrates for high-frequency operation up to hundreds of MHz, enable compact, programmable filtering by adjusting tap weights via external resistors or diodes.[29] Despite their efficacy, analog matched filters face limitations such as bandwidth constraints from material propagation speeds and temperature sensitivity, which can shift delay characteristics in SAW devices by several parts per million per degree Celsius, degrading performance in varying environments. They found extensive use in legacy radar systems for pulse compression and detection prior to widespread digital adoption.[29][31][10] In ideal conditions, these realizations attain the theoretical maximum signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by fully correlating the signal energy against white noise, but they remain highly sensitive to mismatches like waveform distortion or imprecise weighting, which can reduce output peak amplitude by factors exceeding 3 dB.[30][32]Discrete-Time Approximation

In discrete-time systems, the matched filter approximates the continuous-time filter by processing sampled versions of the received signal and the known signal , where the continuous impulse response is discretized accordingly.[33] The discrete-time matched filter is implemented as a finite impulse response (FIR) filter with coefficients for , where are the samples of the known signal of length and * denotes complex conjugation.[33] The filter output is the convolution of the received signal samples with : This operation peaks at the time index corresponding to signal presence, maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for white noise.[33] Equivalently, the matched filter computes the cross-correlation between and , given by , where denotes convolution.[34] For computation, the direct form evaluates the convolution sum explicitly, requiring operations for signals of length .[34] For longer signals, fast Fourier transform (FFT)-based methods are preferred, leveraging the convolution theorem to achieve complexity by transforming to the frequency domain, multiplying, and inverse transforming.[34] Finite-precision arithmetic in digital implementations introduces quantization noise, which degrades the output SNR by adding errors in coefficient storage and arithmetic operations.[35] This effect is particularly pronounced in low-bit-depth systems, where round-off errors accumulate, reducing detection performance.[35] Oversampling the input signal—sampling at a rate higher than the Nyquist rate—mitigates this by spreading the quantization noise over a wider bandwidth, allowing subsequent low-pass filtering to suppress out-of-band noise and effectively increase SNR by up to 3 dB per doubling of the sampling rate.[36] Practical realizations occur in digital signal processing (DSP) chips, which execute the FIR convolution or FFT algorithms in real time.[37] Software libraries facilitate prototyping; for instance, MATLAB'sxcorr function computes the cross-correlation directly, enabling matched filter simulation via xcorr(r, s).[38]

![{\displaystyle \ y[n]=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }h[n-k]x[k],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/70eeb69f981b478fdccd8fed054f8728c91227aa)

![{\displaystyle x[k]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/19b6396a35db17413c0052c56544ed76ac0f3b30)

![{\displaystyle y[n]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/305428e6d1fb59cd0163a7a96ace52292a262afa)

![{\displaystyle \ y=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }h^{*}[k]x[k]=h^{\mathrm {H} }x=h^{\mathrm {H} }s+h^{\mathrm {H} }v=y_{s}+y_{v}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aad4d727dc211aea3da1ad28d52ae175f2a26155)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {SNR} ={\frac {|{(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}^{\mathrm {H} }(R_{v}^{-1/2}s)|^{2}}{{(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}^{\mathrm {H} }(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}}\leq {\frac {\left[{(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}^{\mathrm {H} }(R_{v}^{1/2}h)\right]\left[{(R_{v}^{-1/2}s)}^{\mathrm {H} }(R_{v}^{-1/2}s)\right]}{{(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}^{\mathrm {H} }(R_{v}^{1/2}h)}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f268f11037b29e4567a27b87e25079d128d0a65b)

![{\displaystyle \ j^{*},\mu ^{*}=\arg \min _{j,\mu }\left[\sum _{k}(s_{k}+v_{k})^{2}+\mu ^{2}\sum _{k}h_{j-k}^{2}-2\mu \sum _{k}s_{k}h_{j-k}-2\mu \sum _{k}v_{k}h_{j-k}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/181ae999bd0cd1c27f320758f55078a262bb9c4c)

![{\displaystyle \ j^{*},\mu ^{*}=\arg \max _{j,\mu }\left[2\mu \sum _{k}s_{k}h_{j-k}-\mu ^{2}\sum _{k}h_{j-k}^{2}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/61c23186891cef0462083a2263e9127219e99212)