Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Clindamycin.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Clindamycin

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Clindamycin

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

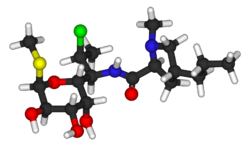

Clindamycin is a semisynthetic lincosamide antibiotic derived from the natural antibiotic lincomycin through a 7(S)-chloro-substitution of the 7(R)-hydroxyl group, belonging to the class of lincomycin antibiotics that inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit.[1][2] It is primarily bacteriostatic but can be bactericidal against certain organisms at higher concentrations, making it effective against a range of susceptible Gram-positive aerobes, anaerobes, and some protozoa.[2][3]

Clindamycin is FDA-approved for treating serious infections such as septicemia, intra-abdominal infections, lower respiratory tract infections, gynecological infections, bone and joint infections, and skin and soft tissue infections caused by susceptible bacteria, including streptococci, staphylococci, and anaerobes like Bacteroides species.[2] It serves as an alternative for patients allergic to penicillin or when less toxic antibiotics are inappropriate, and is also used off-label or topically for conditions like acne vulgaris, bacterial vaginosis, toxoplasmosis, and malaria.[2][3] Additionally, it is employed for endocarditis prophylaxis in at-risk patients undergoing dental procedures.[3]

Available in multiple formulations, clindamycin can be administered orally (as capsules or solution), intramuscularly, intravenously, topically (gels, lotions, creams), or intravaginally, with dosing adjusted based on infection severity and patient factors.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] However, its use carries significant risks, including Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) and pseudomembranous colitis, which can range from mild to fatal and may occur even months after treatment due to disruption of normal intestinal flora.[1][3] Other common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash, with contraindications for those with a history of hypersensitivity to clindamycin or lincomycin; use with caution in patients with prior pseudomembranous colitis.[2][1]