Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chlamydia trachomatis

View on Wikipedia

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

|---|---|

| |

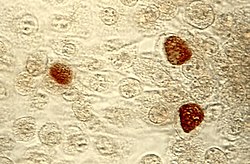

| Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions (brown) within host cells | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota |

| Class: | Chlamydiia |

| Order: | Chlamydiales |

| Family: | Chlamydiaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydia |

| Species: | C. trachomatis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chlamydia trachomatis (/kləˈmɪdiə trəˈkoʊmətɪs/) is a Gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium responsible for chlamydia and trachoma. C. trachomatis exists in two forms, an extracellular infectious elementary body (EB) and an intracellular non-infectious reticulate body (RB).[2] The EB attaches to host cells and enter the cell using effector proteins, where it transforms into the metabolically active RB. Inside the cell, RBs rapidly replicate before transitioning back to EBs, which are then released to infect new host cells.[3]

The earliest description of C. trachomatis was in 1907 by Stanislaus von Prowazek and Ludwig Halberstädter as a protozoan.[4] It was later thought to be a virus due to its small size and inability to grow in laboratories. It was not until 1966 when it was discovered as a bacterium by electron microscopy after its internal structures were visually observed.

There are currently 18 serovars of C. trachomatis, each associated with specific diseases affecting mucosal cells in genital tracts and ocular systems.[3] Infections are often asymptomatic, but can lead to severe complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease in women and epididymitis in men. The bacterium also causes urethritis, conjunctivitis, and lymphogranuloma venereum in both sexes. C. trachomatis genitourinary infections are diagnosed more frequently in women than in men, with the highest prevalence occurring in females aged 15 to 19 years of age.[5][6][7] Infants born from mothers with active chlamydia infections have a pulmonary infection rate that is less than 10%.[8] Globally, approximately 84 million people are affected by C. trachomatis eye infections, with 8 million cases resulting in blindness.[9] C. trachomatis is the leading infectious cause of blindness and the most common sexually transmitted bacterium.[3]

The impact of C. trachomatis on human health has been driving vaccine research since its discovery.[10] Currently, no vaccines are available, largely due to the complexity of the immunological pathways involved in C. trachomatis, which remain poorly understood. However, C. trachomatis infections may be treated with several antibiotics, with tetracycline being the preferred option.[11][12]

Description

[edit]Chlamydia trachomatis is a gram-negative bacterium that replicates exclusively within a host cell, making it an obligate intracellular pathogen.[3] Over the course of its life cycle, C. trachomatis takes on two distinct forms to facilitate infection and replication. Elementary bodies (EBs) are 200 to 400 nanometers across and are surrounded by a rigid cell wall that enables them to survive in an extracellular form.[3][10] When an EB encounters a susceptible host cell, it binds to the cell surface and is internalized.[3] The second form, reticulate bodies (RBs) are 600 to 1500 nanometers across, and are found only within host cells.[10] RBs have increased metabolic activity and are adapted for replication. Neither form is motile.[10]

The evolution of C. trachomatis includes a reduced genome of approximately 1.04 megabases, encoding approximately 900 genes.[3] In addition to the chromosome that contains most of the genome, nearly all C. trachomatis strains carry a 7.5 kilobase plasmid that contains 8 genes.[10] The role of this plasmid is unknown, although strains without the plasmid have been isolated, suggesting it is not essential for bacterial survival.[10] Several important metabolic functions are not encoded in the C. trachomatis genome and are instead scavenged from the host cell.[3]

Carbohydrate metabolism

[edit]C. trachomatis has a reduced metabolic capacity due to its smaller genome, which lacks genes for many biosynthetic pathways including those required for complete carbohydrate metabolism.[3][13] The bacterium is largely dependent on the host cell for metabolic intermediates and energy, particularly in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).[13] C. trachomatis lacks several enzymes necessary for independent glucose metabolism, and instead utilizes two ATP/ADP translocases (Npt1 and Npt2) to import ATP from the host cell.[14] Other metabolites including amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids are also transported from the host.[13][15]

A critical enzyme involved in glycolysis, hexokinase, is absent in C. trachomatis, preventing the production of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P). Instead, G6P from the host cell is taken up by the metabolically active reticulate bodies (RBs) through a G6P transporter (UhpC antiporter).[15][13] Although C. trachomatis lacks a complete independent glycolysis pathway, it has genes encoding for all the enzymes required for the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP), gluconeogenesis, and glycogen synthesis and degradation.[13]

A suppressor of glycolysis, p53, is expressed less frequently in C. trachomatis-infected cells, increasing the rate at which glycolysis occurs, even in the presence of oxygen.[13] As a result, C. trachomatis infection is associated with increased production of pyruvate, lactate, and glutamate by the host cell due to activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2 enzyme limiting conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-coenzyme A.[13] The pyruvate is instead turned into lactate, which allows the bacterium to grow almost unobstructed by immune response due to the acidic properties of lactate.[13][failed verification][16] Excess glycolytic products are, in turn, brought into the host's PPP to create nucleotides and for biosynthesis, again feeding the growth needs of the bacterium.[13] This type of growth is very similar to the Warburg effect observed in cancer cells.[13]

Life cycle

[edit]

Like other Chlamydia species, C. trachomatis has a life cycle consisting of two morphologically distinct forms. First, C. trachomatis attaches to a new host cell as a small spore-like form called the elementary body.[17] The elementary body enters the host cell, surrounded by a host vacuole, called an inclusion.[17] Within the inclusion, C. trachomatis transforms into a larger, more metabolically active form called the reticulate body.[17] The reticulate body substantially modifies the inclusion, making it a more hospitable environment for rapid replication of the bacteria, which occurs over the following 30 to 72 hours.[17] The massive number of intracellular bacteria then transition back to resistant elementary bodies before causing the cell to rupture and being released into the environment.[17] These new elementary bodies are then shed in the semen or released from epithelial cells of the female genital tract and attach to new host cells.[18]

Classification

[edit]Chlamydia trachomatis are bacteria in the genus Chlamydia, a group of obligate intracellular parasites of eukaryotic cells.[3] Chlamydial cells cannot carry out energy metabolism and they lack biosynthetic pathways.[19]

Chlamydia trachomatis strains are generally divided into three biovars based on the type of human disease they cause. Each biovar is further subdivided into several serovars based on the surface antigens recognized by the immune system.[3] Serovars A through C cause trachoma, which is the world's leading cause of preventable infectious blindness.[20] Serovars D through K infect the genital tract, causing pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancies, and infertility. Serovars L1 through L3 cause an invasive infection of the lymph nodes near the genitals, called lymphogranuloma venereum.[3]

Chlamydia trachomatis is thought to have diverged from other Chlamydia species around 6 million years ago. This genus contains a total of nine species: C. trachomatis, C. muridarum, C. pneumoniae, C. pecorum, C. suis, C. abortus, C. felis, C. caviae, and C. psittaci. The closest relative to C. trachomatis is C. muridarum, which infects mice.[17] C. muridarum was formerly known as the "mouse pneumonitis" (MoPn) biovar of C. trachomatis.[21][22] C. trachomatis along with C. pneumoniae have been found to infect humans to a greater extent. C. trachomatis exclusively infects humans. C. pneumoniae is found to also infect horses, marsupials, and frogs. Some of the other species can have a considerable impact on human health due to their known zoonotic transmission.[3]

|

Strains that cause lymphogranuloma venereum (Serovars L1 to L3) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Role in disease

[edit]Clinical signs and symptoms of C. trachomatis infection in the genitalia present as the chlamydia infection, which may be asymptomatic or may resemble a gonorrhea infection.[11] Both are common causes of multiple other conditions including pelvic inflammatory disease and urethritis.[5]

Chlamydia trachomatis is the single most important infectious agent associated with blindness (trachoma), and it also affects the eyes in the form of inclusion conjunctivitis and is responsible for about 19% of adult cases of conjunctivitis.[6]

Chlamydia trachomatis in the lungs presents as the chlamydia pneumoniae respiratory infection and can affect all ages.[23]

Pathogenesis

[edit]Elementary bodies are generally present in the semen of infected men and vaginal secretions of infected women.[18] When they come into contact with a new host cell, the elementary bodies bind to the cell via interaction between adhesins on their surface and several host receptor proteins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans.[3] Once attached, the bacteria inject various effector proteins into the host cell using a type three secretion system.[3] These effectors trigger the host cell to take up the elementary bodies and prevent the cell from triggering apoptosis.[3] Within 6 to 8 hours after infection, the elementary bodies transition to reticulate bodies and a number of new effectors are synthesized.[3] These effectors include a number of proteins that modify the inclusion membrane (Inc proteins), as well as proteins that redirect host vesicles to the inclusion.[3] 8 to 16 hours after infection, another set of effectors are synthesized, driving acquisition of nutrients from the host cell.[3] At this stage, the reticulate bodies begin to divide, coinciding with the expansion of the inclusion.[3] If several elementary bodies have infected a single cell, their inclusions will fuse at this point to create a single large inclusion in the host cell.[3] From 24 to 72 hours after infection, reticulate bodies transition to elementary bodies which are released either by lysis of the host cell or extrusion of the entire inclusion into the host genital tract.[3]

Virulence factors

[edit]The chlamydial plasmid, a DNA molecule existing separately from the genome of C. trachomatis, functions to enhance genetic diversity via the genes encoded.[24] The plasmid gene protein 3 (pgp3) has been linked to the establishment of persistent infection within the genital tract by suppressing the host immune response.[25]

Polymorphic outer membrane proteins (Pmp proteins) on the surface of C. trachomatis use tropism to bind specific host cell receptors, which in turn initiates infection.[26] Pmp proteins B, D, and H have been most associated with eliciting a pro-inflammatory response through the release of cytokines.[27]

CPAF (Chlamydia Protease-like Activity Factor) functions by preventing the host from triggering the proper immune response. C. trachomatis use of CPAF targets and cleaves proteins that restructure the Golgi apparatus and activate DNA repair so that C. trachomatis is able to use the host cell machinery and proteins to its advantage.[28]

Presentation

[edit]Most people infected with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic. However, the bacteria can present in one of three ways: genitourinary (genitals), pulmonary (lungs), and ocular (eyes).[7]

Genitourinary cases can include genital discharge, vaginal bleeding, itchiness (pruritus), painful urination (dysuria), among other symptoms.[8] Often, symptoms are similar to those of a urinary tract infection.[citation needed]

When C. trachomatis presents in the eye in the form of trachoma, it begins by gradually thickening the eyelids and eventually begins to pull the eyelashes into the eyelid.[29] In the form of inclusion conjunctivitis, the infection presents with redness, swelling, mucopurulent discharge from the eye, and most other symptoms associated with adult conjunctivitis.[6]

Chlamydia trachomatis may latently infect the chorionic villi tissues of pregnant women, thereby impacting pregnancy outcome.[30]

Prevalence

[edit]Three times as many women are diagnosed with genitourinary C. trachomatis infections as men. Women aged 15–19 have the highest prevalence, followed by women aged 20–24, although the rate of increase of diagnosis is greater for men than for women. Risk factors for genitourinary infections include unprotected sex with multiple partners, lack of condom use, and low socioeconomic status living in urban areas.[7]

Pulmonary infections can occur in infants born to women with active chlamydia infections, although the rate of infection is less than 10%.[8]

Ocular infections take the form of inclusion conjunctivitis or trachoma, both in adults and children. About 84 million worldwide develop C. trachomatis eye infections and 8 million are blinded as a result of the infection.[9] Trachoma is the primary source of infectious blindness in some parts of rural Africa and Asia and is a neglected tropical disease that has been targeted by the World Health Organization for elimination by 2020.[31] Inclusion conjunctivitis from C. trachomatis is responsible for about 19% of adult cases of conjunctivitis.[6]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment depends on the infection site, age of the patient, and whether another infection is present. Having a C. trachomatis and one or more other sexually transmitted infections at the same time is possible. Treatment is often done with both partners simultaneously to prevent reinfection. C. trachomatis may be treated with several antibiotic medications, including azithromycin, erythromycin, ofloxacin,[11] and tetracycline.

Tetracycline is the most preferred antibiotic to treat C.trachomatis and has the highest success rate. Azithromycin and doxycycline have equal efficacy to treat C. trachomatis with 97 and 98 percent success, respectively. Azithromycin is dosed as a 1 gram tablet that is taken by mouth as a single dose, primarily to help with concerns of non-adherence.[12] Treatment with generic doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days has equal success with expensive delayed-release doxycycline 200 mg once a day for 7 days.[12] Erythromycin is less preferred as it may cause gastrointestinal side effects, which can lead to non-adherence. Levofloxacin and ofloxacin are generally no better than azithromycin or doxycycline and are more expensive.[12]

If treatment is necessary during pregnancy, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tetracycline, and doxycycline are not prescribed. In the case of a patient who is pregnant, the medications typically prescribed are azithromycin, amoxicillin, and erythromycin. Azithromycin is the recommended medication and is taken as a 1 gram tablet taken by mouth as a single dose.[12] Despite amoxicillin having fewer side effects than the other medications for treating antenatal C. trachomatis infection, there have been concerns that pregnant women who take penicillin-class antibiotics can develop a chronic persistent chlamydia infection.[32] Tetracycline is not used because some children and even adults can not withstand the drug, causing harm to the mother and fetus.[12] Retesting during pregnancy can be performed three weeks after treatment. If the risk of reinfection is high, screening can be repeated throughout pregnancy.[11]

If the infection has progressed, ascending the reproductive tract and pelvic inflammatory disease develops, damage to the fallopian tubes may have already occurred. In most cases, the C. trachomatis infection is then treated on an outpatient basis with azithromycin or doxycycline. Treating the mother of an infant with C. trachomatis of the eye, which can evolve into pneumonia, is recommended.[11] The recommended treatment consists of oral erythromycin base or ethylsuccinate 50 mg/kg/day divided into four doses daily for two weeks while monitoring for symptoms of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) in infants less than 6 weeks old.[12]

There have been a few reported cases of C.trachomatis strains that were resistant to multiple antibiotic treatments. However, as of 2018, this is not a major cause of concern as antibiotic resistance is rare in C.trachomatis compared to other infectious bacteria.[33]

Laboratory tests

[edit]Chlamydia species are readily identified and distinguished from other Chlamydia species using DNA-based tests. Tests for Chlamydia can be ordered from a doctor, a lab or online.[34]

Most strains of C. trachomatis are recognized by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to epitopes in the VS4 region of MOMP.[35] However, these mAbs may also cross-react with two other Chlamydia species, C. suis and C. muridarum.[citation needed]

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) tests find the genetic material (DNA) of Chlamydia bacteria. These tests are the most sensitive tests available, meaning they are very accurate and are unlikely to have false-negative test results. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is an example of a nucleic acid amplification test. This test can also be done on a urine sample, urethral swabs in men, or cervical or vaginal swabs in women.[36]

- Nucleic acid hybridization tests (DNA probe test) also find Chlamydia DNA. A probe test is very accurate but is not as sensitive as NAATs.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, EIA) finds substances (Chlamydia antigens) that trigger the immune system to fight Chlamydia infection. Chlamydia Elementary body (EB)-ELISA could be used to stratify different stages of infection based upon Immunoglobulin-γ status of the infected individuals [37]

- Direct fluorescent antibody test also finds Chlamydia antigens.

- Chlamydia cell culture is a test in which the suspected Chlamydia sample is grown in a vial of cells. The pathogen infects the cells, and after a set incubation time (48 hours), the vials are stained and viewed on a fluorescent light microscope. Cell culture is more expensive and takes longer (two days) than the other tests. The culture must be grown in a laboratory.[38]

Research

[edit]Studies have revealed antibiotic resistance in Chlamydia trachomatis. Mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, including A2057G and A2059G, have been identified as significant contributors to resistance against azithromycin, a commonly used treatment. This resistance is linked to treatment failures and persistent infections, necessitating ongoing research into alternative antibiotics, such as moxifloxacin, as well as non-antibiotic approaches like bacteriophage therapy. These innovations aim to combat resistance while reducing the overall burden of antibiotic misuse, which has been closely associated with the rise of resistant strains in C. trachomatis populations.[39]

Additionally, diagnostic improvements have played a vital role in identifying C. trachomatis infections more efficiently. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as DNA- and RNA-based tests, have shown high sensitivity and specificity, making them the gold standard for detecting asymptomatic infections. NAATs have facilitated broader screening programs, particularly in high-risk populations, and are integral to public health initiatives aimed at controlling the spread of C. trachomatis. Research continues into point-of-care diagnostic tools, which promise faster results and greater accessibility, especially in low-resource settings.[40]

Recent studies have challenged traditional assumptions about the transmission and persistence of C. trachomatis in the human body. In a study of heterosexual women with no history of receptive anal intercourse, researchers identified highly viable C. trachomatis in deep rectal samples (using a proctoscope), suggesting that gastrointestinal colonization may occur through non-anal routes such as vaginorectal transfer or oral exposure. Notably, the rectal and cervical strains often carried distinct MLST types, indicating that rectal infections may persist independently of concurrent genital infection. These findings point to the gastrointestinal tract as a potential long-term reservoir for C. trachomatis, with implications for diagnostics, treatment strategies, and reinfection risk.[41]

In the area of vaccine development, creating an effective vaccine for C. trachomatis has proven challenging due to the complex immune responses the bacterium elicits. Subunit vaccines, which target outer membrane proteins like MOMP (Major Outer Membrane Protein) and polymorphic membrane proteins (Pmp), are being explored in both animal models and early human trials. While these vaccines show promise in inducing partial immunity in murine models, further research is needed to evaluate their efficacy in humans. The goal is to develop a vaccine that can prevent reinfection without causing harmful inflammatory responses.[42]

History

[edit]Chlamydia trachomatis was first described in 1907 by Stanislaus von Prowazek and Ludwig Halberstädter in scrapings from trachoma cases.[43][17] Thinking they had discovered a "mantled protozoan", they named the organism "Chlamydozoa" from the Greek "Chlamys" meaning mantle.[17] Over the next several decades, "Chlamydozoa" was thought to be a virus as it was small enough to pass through bacterial filters and unable to grow on known laboratory media.[17] However, in 1966, electron microscopy studies showed C. trachomatis to be a bacterium.[17] This is essentially due to the fact that they were found to possess DNA, RNA, and ribosomes like other bacteria. It was originally believed that Chlamydia lacked peptidoglycan because researchers were unable to detect muramic acid in cell extracts.[44] Subsequent studies determined that C. trachomatis synthesizes both muramic acid and peptidoglycan, but relegates it to the microbe's division septum and does not utilize it for construction of a cell wall.[45][46] The bacterium is still classified as gram-negative.[47]

Chlamydia trachomatis agent was first cultured and isolated in the yolk sacs of eggs by Tang Fei-fan et al. in 1957.[48] This was a significant milestone because it became possible to preserve these agents, which could then be used for future genomic and phylogenetic studies. The isolation of C. trachomatis coined the term isolate to describe how C. trachomatis has been isolated from an in vivo setting into a "strain" in cell culture.[49] Only a few "isolates" have been studied in detail, limiting the information that can be found on the evolutionary history of C. trachomatis.[48][50]

Evolution

[edit]In the 1990s it was shown that there are several species of Chlamydia. Chlamydia trachomatis was first described in historical records in Ebers papyrus written between 1553 and 1550 BC.[51] In the ancient world, it was known as the blinding disease trachoma. The disease may have been closely linked with humans and likely predated civilization.[52] It is now known that C. trachomatis comprises 19 serovars which are identified by monoclonal antibodies that react to epitopes on the major outer-membrane protein (MOMP).[53] Comparison of amino acid sequences reveals that MOMP contains four variable segments: S1,2 ,3 and 4. Different variants of the gene that encodes for MOMP, differentiate the genotypes of the different serovars. The antigenic relatedness of the serovars reflects the homology levels of DNA between MOMP genes, especially within these segments.[54]

Furthermore, there have been over 220 Chlamydia vaccine trials done on mice and other non-human host species to target C. muridarum and C. trachomatis strains. However, it has been difficult to translate these results to the human species due to physiological and anatomical differences. Future trials are working with closely related species to humans.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ J.P. Euzéby. "Chlamydia". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN (September 2011). "Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (9) e1002258. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. PMC 3178582. PMID 21966270.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J (2016). "Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 14 (6): 385–400. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30. PMC 4886739. PMID 27108705.

- ^ Nunes A, Gomes JP (2014). "Evolution, Phylogeny, and molecular epidemiology of Chlamydia". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 23: 49–64. Bibcode:2014InfGE..23...49N. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.029. PMID 24509351.

- ^ a b Fredlund H, Falk L, Jurstrand M, Unemo M (2004). "Molecular genetic methods for diagnosis and characterisation of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: impact on epidemiological surveillance and interventions". APMIS. 112 (11–12): 771–84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11211-1205.x. PMID 15638837. S2CID 25249521.

- ^ a b c d Rapoza, Peter A.; Quinn, Thomas C.; Terry, Arlo C.; Gottsch, John D.; Kiessling, Lou Ann; Taylor, Hugh R. (1990-02-01). "A Systematic Approach to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Conjunctivitis". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 109 (2): 138–142. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)75977-X. ISSN 0002-9394. PMID 2154106.

- ^ a b c "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Mishori R, McClaskey EL, WinklerPrins VJ (15 December 2012). "Chlamydia Trachomatis Infections: Screening, Diagnosis, and Management". American Family Physician. 86 (12): 1127–1132. PMID 23316985.

- ^ a b "Trachoma". Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Kuo CC, Stephens RS, Bavoil PM, Kaltenboeck B (2015). "Chlamydia". In Whitman WB (ed.). Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–28. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm00364. ISBN 978-1-118-96060-8.

- ^ a b c d e Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M (September 2013). "Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update". Indian J. Med. Res. 138 (3): 303–16. PMC 3818592. PMID 24135174.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chlamydial Infections in Adolescents and Adults". Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rother, Marion; Teixeira da Costa, Ana Rita; Zietlow, Rike; Meyer, Thomas F.; Rudel, Thomas (2019). "Modulation of Host Cell Metabolism by Chlamydia trachomatis". Microbiology Spectrum. 7 (3). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.BAI-0012-2019. ISSN 2165-0497. PMC 11026074. PMID 31111817.

- ^ Liang, Pingdong; Rosas-Lemus, Mónica; Patel, Dhwani; Fang, Xuan; Tuz, Karina; Juárez, Oscar (2017-11-09). "Dynamic energy dependency of Chlamydia trachomatis on host cell metabolism during intracellular growth: Role of sodium-based energetics in chlamydial ATP generation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 293 (2): 510–522. doi:10.1074/jbc.M117.797209. PMC 5767857. PMID 29123027.

- ^ a b N'Gadjaga, Maimouna D.; Perrinet, Stéphanie; Connor, Michael G.; Bertolin, Giulia; Millot, Gaël A.; Subtil, Agathe (2022-08-02). "Chlamydia trachomatis development requires both host glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation but has only minor effects on these pathways". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 298 (9) 102338. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102338. PMC 9449673. PMID 35931114.

- ^ Tymoczko, John L.; Berg, Jeremy M.; Stryer, Lubert (2015). Biochemistry, a short course (3rd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman & Company, a Macmillan Education imprint. ISBN 978-1-4641-2613-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nunes A, Gomes JP (2014). "Evolution, Phylogeny, and molecular epidemiology of Chlamydia". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 23: 49–64. Bibcode:2014InfGE..23...49N. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.029. PMID 24509351.

- ^ a b Witkin SS, Minis E, Athanasiou A, Leizer J, Linhares IM (2017). "Chlamydia trachomatis:the persistent pathogen". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 24 (10): e00203–17. doi:10.1128/CVI.00203-17. PMC 5629669. PMID 28835360.

- ^ Becker, Y. (1996). Molecular evolution of viruses: Past and present (4th ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8091/.

- ^ Burton, Matthew J.; Trachoma: an overview, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 84, Issue 1, 1 December 2007, Pages 99–116, https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm034

- ^ Read, TD; Brunham, RC; Shen, C; Gill, SR; Heidelberg, JF; White, O; Hickey, EK; Peterson, J; Utterback, T; Berry, K; Bass, S; Linher, K; Weidman, J; Khouri, H; Craven, B; Bowman, C; Dodson, R; Gwinn, M; Nelson, W; DeBoy, R; Kolonay, J; McClarty, G; Salzberg, SL; Eisen, J; Fraser, CM (15 March 2000). "Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39". Nucleic Acids Research. 28 (6): 1397–406. doi:10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. PMC 111046. PMID 10684935.

- ^ Carlson, John H.; Whitmire, William M.; Crane, Deborah D.; Wicke, Luke; Virtaneva, Kimmo; Sturdevant, Daniel E.; Kupko, John J.; Porcella, Stephen F.; Martinez-Orengo, Neysha; Heinzen, Robert A.; Kari, Laszlo; Caldwell, Harlan D. (June 2008). "The Chlamydia trachomatis Plasmid Is a Transcriptional Regulator of Chromosomal Genes and a Virulence Factor". Infection and Immunity. 76 (6): 2273–2283. doi:10.1128/iai.00102-08. PMC 2423098. PMID 18347045.

- ^ Gautam, Jeevan; Krawiec, Conrad (2022), "Chlamydia Pneumonia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32809709, retrieved 2022-06-26

- ^ Rockey, Daniel D. (2011-10-24). "Unraveling the basic biology and clinical significance of the chlamydial plasmid". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 208 (11): 2159–2162. doi:10.1084/jem.20112088. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC 3201210. PMID 22025500.

- ^ Yang, Chunfu; Kari, Laszlo; Lei, Lei; Carlson, John H.; Ma, Li; Couch, Claire E.; Whitmire, William M.; Bock, Kevin; Moore, Ian; Bonner, Christine; McClarty, Grant; Caldwell, Harlan D. (2020-08-25). Ouellette, Scot P. (ed.). "Chlamydia trachomatis Plasmid Gene Protein 3 Is Essential for the Establishment of Persistent Infection and Associated Immunopathology". mBio. 11 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.01902-20. ISSN 2161-2129. PMC 7439461. PMID 32817110.

- ^ Debrine, Abigail M.; Karplus, P. Andrew; Rockey, Daniel D. (2023-12-12). Shen, Li (ed.). "A structural foundation for studying chlamydial polymorphic membrane proteins". Microbiology Spectrum. 11 (6): e0324223. doi:10.1128/spectrum.03242-23. ISSN 2165-0497. PMC 10715098. PMID 37882824.

- ^ Byrne, Gerald I. (2010-06-15). "Chlamydia trachomatis Strains and Virulence: Rethinking Links to Infection Prevalence and Disease Severity". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 201 (S2): 126–133. doi:10.1086/652398. ISSN 0022-1899. PMC 2878587. PMID 20470049.

- ^ A. Conrad, Turner; Yang, Zhangsheng; Ojcius, David; Zhong, Guangming (2013-12-01). "A path forward for the chlamydial virulence factor CPAF". Microbes and Infection. Special issue on pathogenesis and cell corruption by intracellular bacteria. 15 (14): 1026–1032. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2013.09.008. ISSN 1286-4579. PMC 4320975. PMID 24141088.

- ^ Wolle, Meraf A.; West, Sheila K. (2019-03-04). "Ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection: elimination with mass drug administration". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 17 (3): 189–200. doi:10.1080/14787210.2019.1577136. ISSN 1478-7210. PMC 7155971. PMID 30698042.

- ^ Contini C, Rotondo JC, Magagnoli F, Maritati M, Seraceni S, Graziano A, Poggi A, Capucci R, Vesce F, Tognon M, Martini F (2018). "Investigation on silent bacterial infections in specimens from pregnant women affected by spontaneous miscarriage". J Cell Physiol. 234 (1): 100–9107. doi:10.1002/jcp.26952. hdl:11392/2393176. PMID 30078192.

- ^ Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Trachoma interactive fact sheet. http://old.globalnetwork.org/sites/all/modules/globalnetwork/factsheetxml/disease.php?id=9 Accessed February 6, 2011,

- ^ Welsh, L E; Gaydos, C A; Quinn, T C (1992). "In vitro evaluation of activities of azithromycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline against Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 36 (2): 291–294. doi:10.1128/aac.36.2.291. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 188358. PMID 1318677.

- ^ Mestrovic, T (2018). "Molecular Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis resistance to antimicrobial drugs" (PDF). Frontiers in Bioscience. 23 (2): 656–670. doi:10.2741/4611. PMID 28930567. S2CID 11631854.

- ^ "Oral Chlamydia Home Testing, Symptoms and Treatment | myLAB Box™". 2019-04-03.

- ^ Ortiz L, Angevine M, Kim SK, Watkins D, DeMars R (2000). "T-Cell Epitopes in Variable Segments of Chlamydia trachomatis Major Outer Membrane Protein Elicit Serovar-Specific Immune Responses in Infected Humans". Infect. Immun. 68 (3): 1719–23. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.3.1719-1723.2000. PMC 97337. PMID 10678996.

- ^ Price, Malcolm J; Ades, AE; Soldan, Kate; Welton, Nicky J; Macleod, John; Simms, Ian; DeAngelis, Daniela; Turner, Katherine ME; Horner, Paddy J (2016). "The natural history of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: a multi-parameter evidence synthesis". Health Technology Assessment. 20 (22): 1–250. doi:10.3310/hta20220. ISSN 1366-5278. PMC 4819202. PMID 27007215.

- ^ Bakshi, Rakesh; Gupta, Kanupriya; Jordan, Stephen J.; Brown, LaDraka' T.; Press, Christen G.; Gorwitz, Rachel J.; Papp, John R.; Morrison, Sandra G.; Lee, Jeannette Y. (2017-04-21). "Immunoglobulin-Based Investigation of Spontaneous Resolution of Chlamydia trachomatis Infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 215 (11): 1653–1656. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix194. ISSN 1537-6613. PMC 5853778. PMID 28444306.

- ^ "Chlamydia Tests". Sexual Conditions Health Center. WebMD. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ^ Stamm, Walter E. (March 1999). "Chlamydia trachomatis Infections: Progress and Problems". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 179 (s2): S380 – S383. doi:10.1086/513844. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 10081511.

- ^ "Recommendations for the Laboratory-Based Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ Karlsson, Philip A.; Wänn, Mimmi; Wang, Helen; Falk, Lars; Herrmann, Björn (2025-01-10). "Highly viable gastrointestinal Chlamydia trachomatis in women abstaining from receptive anal intercourse". Scientific Reports. 15 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-025-85297-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 11724036. PMID 39794438.

- ^ Yu, Hong; Geisler, William M.; Dai, Chuanbin; Gupta, Kanupriya; Cutter, Gary; Brunham, Robert C. (2024-02-02). "Antibody responses to Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine candidate antigens in Chlamydia-infected women and correlation with antibody-mediated phagocytosis of elementary bodies". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 14. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1342621. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 10869445. PMID 38371301.

- ^ Christensen, Signe; Halili, Maria A.; Strange, Natalie; Petit, Guillaume A.; Huston, Wilhelmina M.; Martin, Jennifer L.; McMahon, Róisín M. (2019). "Oxidoreductase disulfide bond proteins DsbA and DsbB form an active redox pair in Chlamydia trachomatis, a bacterium with disulfide dependent infection and development". PLOS ONE. 14 (9) e0222595. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1422595C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222595. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6752827. PMID 31536549.

- ^ Fox, A., Rogers, J. C., Gilbart, J., Morgan, S., Davis, C. H., Knight, S., & Wyrick, P. B. (1990). Muramic acid is not detectable in Chlamydia psittaci or Chlamydia trachomatis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Infection and immunity, 58(3), 835–7.

- ^ Packiam, Mathanraj; Weinrick, Brian; Jacobs, William R.; Maurelli, Anthony T. (2015-09-15). "Structural characterization of muropeptides from Chlamydia trachomatis peptidoglycan by mass spectrometry resolves "chlamydial anomaly"". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (37): 11660–11665. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11211660P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514026112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4577195. PMID 26290580.

- ^ Liechti, G. W.; Kuru, E.; Hall, E.; Kalinda, A.; Brun, Y. V.; VanNieuwenhze, M.; Maurelli, A. T. (February 2014). "A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis". Nature. 506 (7489): 507–510. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..507L. doi:10.1038/nature12892. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 3997218. PMID 24336210.

- ^ "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b Darougar S, Jones BR, Kinnison JR, Vaughan-Jackson JD, Dunlop EM (1972). "Chlamydial infection. Advances in the diagnostic isolation of Chlamydia, including TRIC agent, from the eye, genital tract, and rectum". Br J Vener Dis. 48 (6): 416–20. doi:10.1136/sti.48.6.416. PMC 1048360. PMID 4651177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clarke, Ian (2011). "Evolution of Chlamydia Trachomatis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1230 (1): E11–8. Bibcode:2011NYASA1230E..11C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06194.x. PMID 22239534. S2CID 5388815.

- ^ Tang FF, Huang YT, Chang HL, Wong KC (1958). "Further studies on the isolation of the trachoma virus". Acta Virol. 2 (3): 164–70. PMID 13594716.

Tang FF, Chang HL, Huang YT, Wang KC (June 1957). "Studies on the etiology of trachoma with special reference to isolation of the virus in chick embryo". Chin Med J. 75 (6): 429–47. PMID 13461224.

Tang FF, Huang YT, Chang HL, Wong KC (1957). "Isolation of trachoma virus in chick embryo". J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1 (2): 109–20. PMID 13502539. - ^ Clarke, Ian N. (2011). "Evolution of Chlamydia trachomatis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1230 (1): E11 – E18. Bibcode:2011NYASA1230E..11C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06194.x. PMID 22239534. S2CID 5388815.

- ^ Weir, E.; Haider, S.; Telio, D. (2004). "Trachoma: Leading cause of infectious blindness". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (8): 1225. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040286. PMC 385350. PMID 15078842.

- ^ Somboonna, Naraporn; Mead, Sally; Liu, Jessica; Dean, Deborah (2008). "Discovering and Differentiating New and Emerging Clonal Populations of Chlamydia trachomatiswith a Novel Shotgun Cell Culture Harvest Assay". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (3): 445–453. doi:10.3201/eid1403.071071. PMC 2570839. PMID 18325260.

- ^ Hayes, L. J.; Pickett, M. A.; Conlan, J. W.; Ferris, S.; Everson, J. S.; Ward, M. E.; Clarke, I. N. (1990). "The major outer-membrane proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars a and B: Intra-serovar amino acid changes do not alter specificities of serovar- and C subspecies-reactive antibody-binding domains". Journal of General Microbiology. 136 (8): 1559–1566. doi:10.1099/00221287-136-8-1559. PMID 1702141.

- ^ Phillips, Samuel; Quigley, Bonnie L.; Timms, Peter (2019). "Seventy Years of Chlamydia Vaccine Research – Limitations of the Past and Directions for the Future". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 70. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00070. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 6365973. PMID 30766521.

Further reading

[edit]- Bellaminutti, Serena; Seracini, Silva; De Seta, Francesco; Gheit, Tarik; Tommasino, Massimo; Comar, Manola (November 2014). "HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis Co-Detection in Young Asymptomatic Women from High Incidence Area for Cervical Cancer". Journal of Medical Virology. 86 (11): 1920–1925. doi:10.1002/jmv.24041. PMID 25132162. S2CID 29787203.