Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

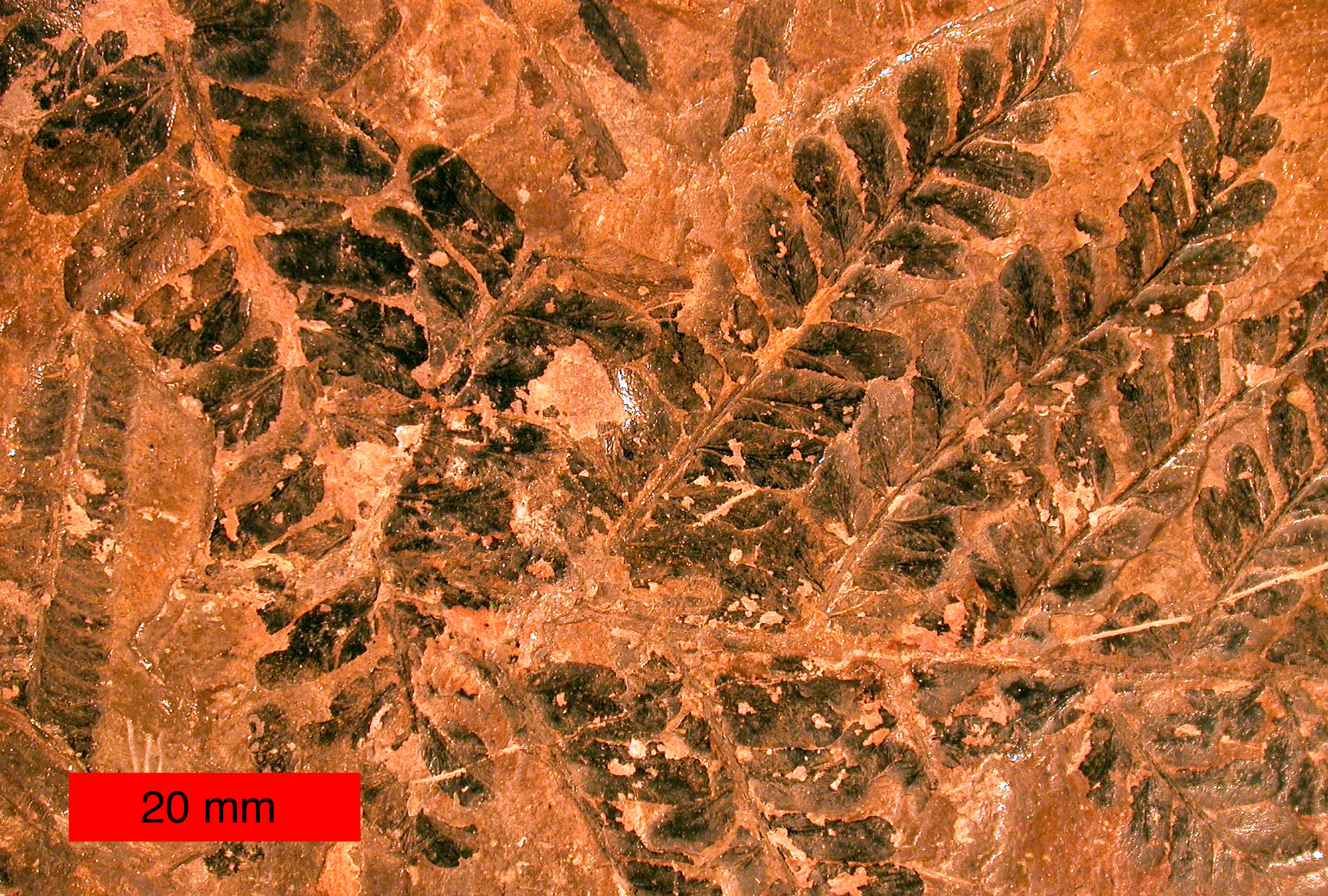

Compression fossil

View on Wikipedia

A compression fossil is a fossil preserved in sedimentary rock that has undergone physical compression. While it is uncommon to find animals preserved as good compression fossils, it is very common to find plants preserved this way. The reason for this is that physical compression of the rock often leads to distortion of the fossil.

The best fossils of leaves are found preserved in fine layers of sediment that have been compressed in a direction perpendicular to the plane of the deposited sediment.[1] Since leaves are basically flat, the resulting distortion is minimal. Plant stems and other three-dimensional plant structures do not preserve as well under compression. Typically, only the basic outline and surface features are preserved in compression fossils; internal anatomy is not preserved. These fossils may be studied while still partially entombed in the sedimentary rock matrix where they are preserved, or once lifted out of the matrix by a peel or transfer technique.[2]

Compression fossils are formed most commonly in environments where fine sediment is deposited, such as in river deltas, lagoons, along rivers, and in ponds. The best rocks in which to find these fossils preserved are clay and shale, although volcanic ash may sometimes preserve plant fossils as well.[3]

Slabs

[edit]

A slab and counter slab, more often called a part and counterpart in paleoentomology[4] and paleobotany,[5] are the matching halves of a compression fossil, a fossil-bearing matrix formed in sedimentary deposits. When excavated the matrix may be split along the natural grain or cleavage of the rock. A fossil embedded in the sediment may then also split down the middle, with fossil remains sticking to both surfaces, or the counter slab may simply show a negative impression or mould of the fossil.[6] Comparing slab and counter slab has led to the exposure of a number of fossil forgeries.

Differences between the impressions on slab and counterslab led astronomer Fred Hoyle and applied physicist Lee Spetner in 1985 to declare that some Archaeopteryx fossils had been forged, a claim dismissed by most palaeontologists.[7]

In its November 1999 edition, National Geographic magazine announced the discovery of Archaeoraptor, a link between dinosaurs and birds, from a 125 million-year-old fossil that had come from Liaoning Province of China. Chinese palaeontologist Xu Xing came into possession of the counter slab through a fossil hunter. On comparing his fossil with images of Archaeoraptor it became evident that it was a composite fake. His note to National Geographic led to consternation and embarrassment. Lewis Simons investigated the matter on behalf of National Geographic. In October 2000, he reported what he termed:

a tale of misguided secrecy and misplaced confidence, of rampant egos clashing, self-aggrandizement, wishful thinking, naïve assumptions, human error, stubbornness, manipulation, backbiting, lying, corruption, and, most of all, abysmal communication.

It was eventually determined that Archaeoraptor had been constructed from parts of an Early Cretaceous bird Yanornis martini and a small dinosaur Microraptor zhaoianus.[8]

In order to increase their profit, fossil hunters and dealers occasionally sell slab and counter slab separately. A reptile fossil also found in Liaoning was described and named Sinohydrosaurus in 1999 by the Beijing Natural History Museum. In the same year the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing described and named Hyphalosaurus lingyuanensis, unaware they were working with the counter slab of the same specimen. Hyphalosaurus is now the accepted name.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Arnold, Chester A. (1947). An Introduction to Paleobotany (1st ed.). New York & London: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 14–40.

- ^ Stewart, Wilson N.; Rothwell, Gar W. (1993). Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–22. ISBN 0-521-38294-7.

- ^ Taylor, Thomas N.; Taylor, Edith L. (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 7–12. ISBN 0-13-651589-4.

- ^ Jepson, J.E.; Ansorge, J.; Jarzembowski, E.A. (2011). "New snakeflies (Insecta: Raphidioptera) from the Lower Cretaceous of the UK, Spain and Brazil". Palaeontology. 54 (2): 385–395. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..385J. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01038.x.

- ^ Channing, A.; Zamuner, A.; Edwards, D.; Guido, D. (2011). "Equisetum thermale sp. nov. (Equisetales) from the Jurassic San Agustin hot spring deposit, Patagonia: Anatomy, paleoecology, and inferred paleoecophysiology". American Journal of Botany. 98 (4): 680–697. Bibcode:2011AmJB...98..680C. doi:10.3732/ajb.1000211. hdl:11336/95234. PMID 21613167.

- ^ ProZ

- ^ New Scientist 14 March 1985

- ^ The Interpretive Mind Archived 1 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Two Guys Fossils Archived 14 September 2012 at archive.today

Compression fossil

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A compression fossil is formed by the physical compression of organic remains into fine-grained sedimentary rock, resulting in a flattened impression where some original organic material may be preserved, often chemically altered into a thin carbon film.[1] This process creates a two-dimensional representation of the organism, with the side retaining more organic residue termed the "part" and the corresponding mold on the opposing rock surface called the "counterpart."[2] Compression fossils are particularly common among plant remains due to the inherently flat and soft nature of plant structures, such as leaves and stems, which compress readily under sediment overburden without significant resistance.[2] In contrast, they are rarer in animals, as the distortion of three-dimensional body forms, especially those with hard parts like shells or bones, typically prevents clear preservation through this mechanism unless the organisms are small or soft-bodied.[2] The term "compression" specifically denotes pressure-induced flattening of the actual organic material, distinguishing it from mere casting, where a mold is filled by minerals to replicate the shape without retaining the original remains.[5]Distinction from Other Fossils

Compression fossils differ from impression fossils primarily in the retention of organic material. While both types result from the flattening of organisms under sedimentary pressure, impressions form as mere external molds or prints on rock surfaces without any preserved organic residue, capturing only the shape and texture of the organism's exterior. In contrast, compression fossils preserve a thin film of carbonized organic matter, often derived from the distillation or carbonization of the original tissues, which provides additional chemical and structural information beyond mere morphology.[6][2][7] Unlike permineralized fossils, which involve the infiltration of minerals such as silica or calcite into the organism's pores and tissues, filling them to create a three-dimensional preservation of the original structure and internal details, compression fossils undergo external flattening without significant mineralization of internals. This process preserves the overall outline and some surface details but results in a two-dimensional representation, as the original volume is lost to compaction. Permineralization, by preserving both external form and internal anatomy in 3D, allows for detailed study of cellular structures, whereas compression emphasizes flattened external features.[8][9][7] Compression fossils also contrast with those preserved in amber or as casts. Amber entrapment encases organisms in hardened resin, maintaining three-dimensional integrity and often soft tissues without flattening or compression, primarily seen in insects, and occasionally in small vertebrates such as lizards and frogs. Cast fossils, formed when sediment fills a mold left by a decayed organism and hardens into a replica, replicate the external shape in 3D but lack original material entirely. Compression, occurring in sedimentary contexts without encasement or molding, focuses on the partial degradation and flattening of organic remains in fine-grained sediments.[10][2][8]| Fossil Type | Preservation Method | Retained Structures | Common Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression | Flattening under sediment with carbonization | 2D outline, carbon film, some surface details | Plants (e.g., leaves, ferns) |

| Impression | External molding without organics | 2D shape and texture only | Plants, invertebrates |

| Permineralized | Mineral infiltration into tissues | 3D form, internal anatomy | Plants (wood), some animals |

| Amber | Encase in resin | 3D unaltered, soft tissues | Insects, occasionally small vertebrates |

| Cast | Sediment filling of mold | 3D external replica | Shells, vertebrates, tracks |