Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pteridospermatophyta

View on Wikipedia

| Pteridospermatophyta | |

|---|---|

| |

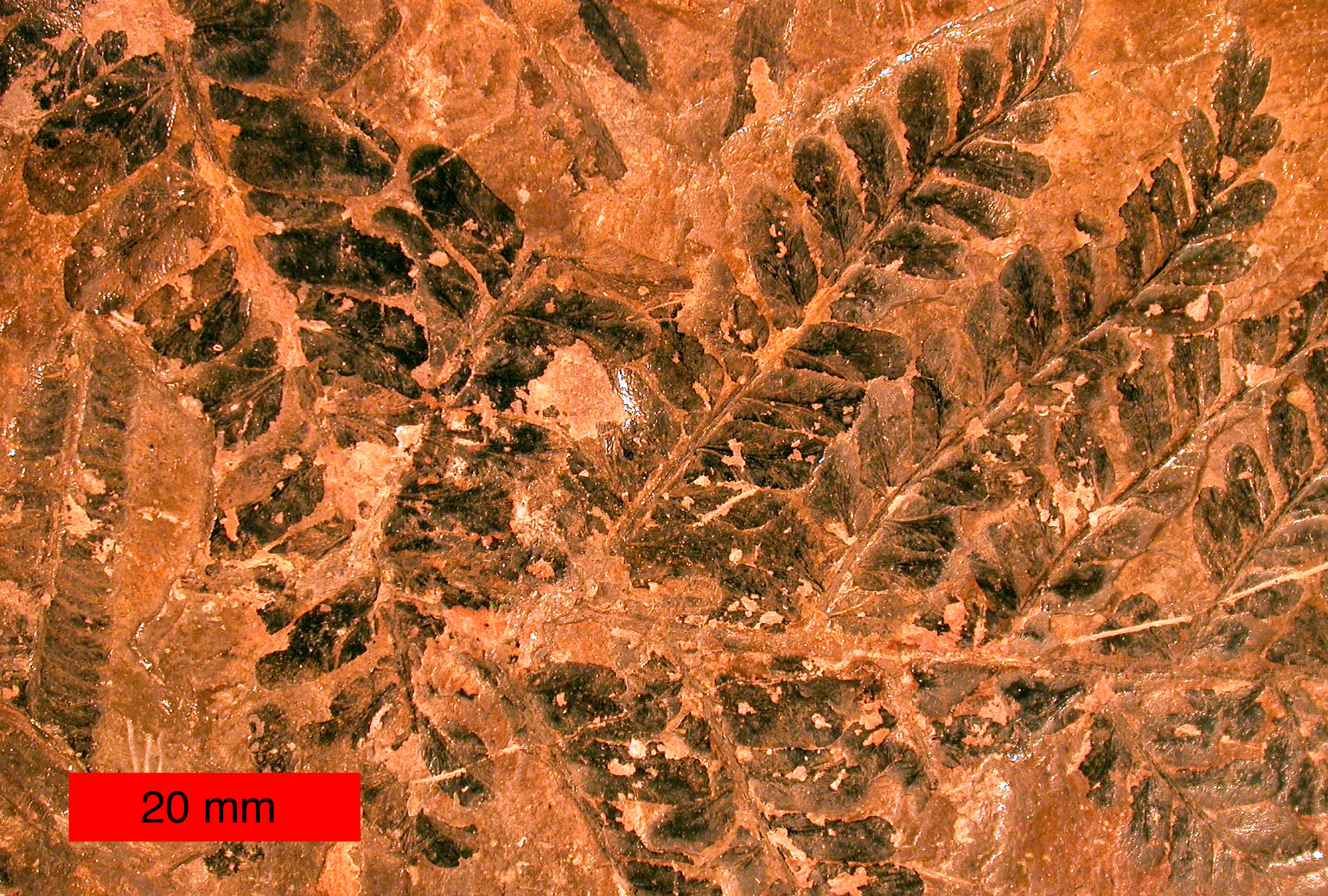

| Fossil seed fern leaves of Neuropteris (Medullosales) from the Late Carboniferous of northeastern Ohio. | |

| |

| Life restoration of Lepidopteris (Peltaspermales) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Spermatophytes |

| Division: | †Pteridospermatophyta |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Excluded | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pteridospermatopsida | |

Pteridospermatophyta, also called pteridosperms or seed ferns, are a polyphyletic[1] grouping of extinct seed-producing plants. The earliest fossil evidence for plants of this type are the lyginopterids of late Devonian age.[2] They flourished particularly during the Carboniferous and Permian periods. Pteridosperms declined during the Mesozoic Era and had mostly disappeared by the end of the Cretaceous Period, though Komlopteris seem to have survived into Eocene times, based on fossil finds in Tasmania.[3]

With regard to the enduring utility of this division, many palaeobotanists still use the pteridosperm grouping in an informal sense to refer to the seed plants that are not angiosperms, coniferoids (conifers or cordaites), ginkgophytes (ginkgos or czekanowskiales), cycadophytes (cycads or bennettites), or gnetophytes. This is particularly useful for extinct seed plant groups whose systematic relationships remain speculative, as they can be classified as pteridosperms with no invalid implications being made as to their systematic affinities. Also, from a purely curatorial perspective the term pteridosperms is a useful shorthand for describing the fern-like fronds that were probably produced by seed plants, which are commonly found in many Palaeozoic and Mesozoic fossil floras.

History of classification

[edit]

The concept of pteridosperms goes back to the late 19th century when palaeobotanists came to realise that many Carboniferous fossils resembling fern fronds had anatomical features more reminiscent of the modern-day seed plants, the cycads. In 1899 the German palaeobotanist Henry Potonié coined the term "Cycadofilices" ("cycad-ferns") for such fossils, suggesting that they were a group of non-seed plants intermediate between the ferns and cycads.[4] Shortly afterwards, the British palaeobotanists Frank Oliver and Dukinfield Henry Scott (with the assistance of Oliver's student at the time, Marie Stopes) made the critical discovery that some of these fronds (genus Lyginopteris) were associated with seeds (genus Lagenostoma) that had identical and very distinctive glandular hairs, and concluded that both fronds and seeds belonged to the same plant.[5] Soon, additional evidence came to light suggesting that seeds were also attached to the Carboniferous fern-like fronds Dicksonites,[6] Neuropteris[7] and Aneimites.[8] Initially it was still thought that they were "transitional fossils" intermediate between the ferns and cycads, and especially in the English-speaking world they were referred to as "seed ferns" or "pteridosperms". Today, despite being regarded by most palaeobotanists as only distantly related to ferns, these spurious names have nonetheless established themselves. Nowadays, four orders of Palaeozoic seed plants tend to be referred to as pteridosperms: Lyginopteridales, Medullosales, Callistophytales and Peltaspermales, with "Mesozoic seed ferns" including the Petriellales, Corystospermales and Caytoniales.[9]

Their discovery attracted considerable attention at the time, as the pteridosperms were the first extinct group of vascular plants to be identified solely from the fossil record. In the 19th century the Carboniferous Period was often referred to as the "Age of Ferns" but these discoveries during the first decade of the 20th century made it clear that the "Age of Pteridosperms" was perhaps a better description.[citation needed]

During the 20th century the concept of pteridosperms was expanded to include various Mesozoic groups of seed plants with fern-like fronds, such as the Corystospermaceae. Some palaeobotanists also included seed plant groups with entire leaves such as the Glossopteridales and Gigantopteridales, which was stretching the concept. In the context of modern phylogenetic models,[10] the groups often referred to as pteridosperms appear to be liberally spread across a range of clades, and many palaeobotanists today would regard pteridosperms as little more than a paraphyletic 'grade-group' with no common lineage.[clarification needed] One of the few characters that may unify the group is that the ovules were borne in a cupule, a group of enclosing branches, but this has not been confirmed for all "pteridosperm" groups.[citation needed]

It has been speculated that some seed fern groups may be close to the ancestry of flowering plants (angiosperms). A 2009 study concluded that "phylogenetic analysis techniques have surpassed the hard data needed to formulate meaningful phylogenetic hypotheses" regarding the relationships of "seed ferns" to living plant groups.[11]

Taxonomy

[edit]Major groups

[edit]- Order †Calamopityales Němejc (1963)

- Order †Corystospermales Petriella (1981) [= Umkomasiales Doweld (2001)]

- Order †Callistophytales Rothwell (1981) emend. Anderson, Anderson & Cleal (2007) [Poroxylales Němejc (1968)]

- Order †Petriellales Taylor et al. (1994)

- Order †Peltaspermales Taylor (1981) [Lepidopteridales Němejc (1968)]

- Order †Gigantopteridales Li & Yao (1983) [Gigantonomiales Meyen (1987)]

- Order †Pentoxylales Pilger & Melchior (1954)

- Order †Glossopteridales Plumstead, 1956

- Order †Caytoniales Gothan (1932)

- Order †Medullosales Corsin (1960)

- Order †Lyginopteridales (Corsin (1960)) Havlena (1961) [Lagenostomatales Seward ex Long (1975); Lyginodendrales Nemejc (1968); Sphenopteridales Schimper 1869]

- Family †Angaranthaceae Naugolnykh (2012)

- Family †Heterangiaceae Němejc (1950) nom. nud.

- Family †Physostomataceae Long (1975)

- Family †Lyginopteridaceae Potonie (1900) emend. Anderson, Anderson & Cleal (2007) [Lagenostomataceae Long (1975; Pityaceae Scott (1909); Lyginodendraceae Scott (1909); Sphenopteridaceae Gopp. (1842); Pseudopecopteridaceae Lesquereux (1884); Megaloxylaceae Scott (1909), nom. rej.; Rhetinangiaceae Scott (1923), nom. rej.; Tetratmemaceae Němejc (1968)]

- Family †Moresnetiaceae Němejc (1963) emend. Anderson, Anderson & Cleal (2007) [Genomospermaceae Long (1975); Elkinsiaceae Rothwell, Scheckler & Gillespie (1989) ex Cleal; Hydraspermaceae]

Other minor groups

[edit]- Class incertae sedis

- Order incertae sedis

- Family ?†Nystroemiaceae Wang & Pfefferkorn (2009)[12]

- †Nystroemia Halle (1927)

- Family †Austrocalyxaceae Vega & Archangelsky (2001)[13]

- †Austrocalyx

- †Polycalyx

- †Rinconadia

- †Jejenia

- †Fedekurtzia (Archangelsky) emend. Coturel et Césari, 2017

- Family ?†Nystroemiaceae Wang & Pfefferkorn (2009)[12]

- Order ?†Alexiales Anderson & Anderson (2003)[14]

- Family †Alexiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- †Alexia Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- Family †Alexiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- Order †Buteoxylonales

- Family †Buteoxylonaceae Barnard & Long (1973)[15]

- †Buteoxylon Barnard & Long (1973)

- †Triradioxylon Barnard & Long (1975)[16]

- Family †Buteoxylonaceae Barnard & Long (1973)[15]

- Order †Dicranophyllales Meyen (1984) emend. Anderson, Anderson & Cleal (2007)

- Family †Dicranophyllaceae Němejc (1959) ex Archangelsky & Cúneo (1990)

- Family †Trichopityaceae Němejc (1968) [Florin emend.]

- †Polyspermophyllum? Archangelsky and Cúneo (1990) (possibly a coniferophyte)

- Order †Erdtmanithecales Friis and Pedersen (1996)

- Order †Fredlindiales Anderson & Anderson (2003)[14]

- Order †Hamshawviales Anderson & Anderson (2003)[14]

- Order †Hlatimbiales Anderson & Anderson (2003)[14]

- Family †Hlatimbiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- †Hlatimbia Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- †Batiopteris Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- Family †Hlatimbiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2003)

- Order †Matatiellales Anderson & Anderson (2003)[14]

- Order †Nilssoniales Darrah (1960) (possibly cycadopsids)

- Order †Phasmatocycadales Doweld (2001) [Taeniopteridales]

- Family †Phasmatocycadaceae Doweld (2001) [Spermopteridaceae Doweld (2001)]

- †Lesleya Lesquereux (1879–80) (otherwise placed as incetae sedis regarding family and order)

- Family †Phasmatocycadaceae Doweld (2001) [Spermopteridaceae Doweld (2001)]

- Order incertae sedis

- Class †Axelrodiopsida Anderson & Anderson (2007)[17]

- Order †Axelrodiales Anderson & Anderson (2007)

- Family †Axelrodiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2007)

- †Axelrodia Cornet (1986)

- †Sanmiguelia Brown (1956)

- †Synangispadixis Cornet (1986)

- Family †Zamiostrobacea Anderson & Anderson (2007)

- †Zamiostrobus Endlicher (1836)

- Family †Axelrodiaceae Anderson & Anderson (2007)

- Order †Axelrodiales Anderson & Anderson (2007)

- Incertae sedis to order and family:

- †Gnetopsis Renault et Zeiller (1884)

- †Pullaritheca Rothwell and Wight (1989)

- †Kegelidium Dolianiti (1954)

- †Ptilozamites

References

[edit]- ^ Elgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Cúneo, N. Rubén (July 2019). "Relictual Lepidopteris (Peltaspermales) from the Early Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation, Patagonia, Argentina". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 180 (6): 578–596. doi:10.1086/703461. ISSN 1058-5893.

- ^ Rothwell G. W.; Scheckler S. E.; Gillespie W. H. (1989). "Elkinsia gen. nov., a Late Devonian gymnosperm with cupulate ovules". Botanical Gazette. 150 (2): 170–189. doi:10.1086/337763. S2CID 84303226.

- ^ McLoughlin S.; Carpenter R.J.; Jordan G.J.; Hill R.S. (2008). "Seed ferns survived the end-Cretaceous mass extinction in Tasmania". American Journal of Botany. 95 (4): 465–471. doi:10.3732/ajb.95.4.465. PMID 21632371.

- ^ Potonié, H. (1899). Lehrbuch der Pflanzenpaläontologie (in German). Berlin, DE.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Oliver, F.W.; Scott, D.H. (1904). "On the structure of the Palaeozoic seed Lagenostoma Lomaxi, with a statement of the evidence upon which it is referred to Lyginodendron". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. 197 (225–238): 193–247. doi:10.1098/rstb.1905.0008.

- ^ Grand'Eury C (1904). "Sur les graines Neuropteridées". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. 140: 782–786.

- ^ Kidston R (1904). "On the fructification of Neuropteris heterophylla, Brongniart". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 197 (225–238): 1–5. doi:10.1098/rstb.1905.0001.

- ^ White D (1904). "The seeds of Aneimites". Smithsonian Institution, Miscellaneous Collection. 47: 322–331.

- ^ Taylor, Edith L., et al. "Mesozoic Seed Ferns: Old Paradigms, New Discoveries." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, vol. 133, no. 1, 2006, pp. 62–82. JSTOR, JSTOR 20063823. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- ^ Hilton, J. & Bateman, R. M. (2006), "Pteridosperms are the backbone of seed-plant phylogeny", Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 33: 119–168, doi:10.3159/1095-5674(2006)133[119:PATBOS]2.0.CO;2, S2CID 86395036

- ^ Taylor, Edith L.; Taylor, Thomas N. (January 2009). "Seed ferns from the late Paleozoic and Mesozoic: Any angiosperm ancestors lurking there?". American Journal of Botany. 96 (1): 237–251. doi:10.3732/ajb.0800202. ISSN 0002-9122. PMID 21628187.

- ^ Wang, Jun; Pfefferkorn, Hermann W. (2010-01-22). "Nystroemiaceae, a new family of Permian gymnosperms from China with an unusual combination of features". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1679): 301–309. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0913. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2842674. PMID 19656793.

- ^ Vega, Juan Carlos; Archangelsky, Sergio (2001-04-25). "Austrocalyxaeae, a new pteridoserm family from Gondwana". Palaeontographica Abteilung B. 257 (1–6): 1–16. Bibcode:2001PalAB.257....1V. doi:10.1127/palb/257/2001/1. S2CID 248282839.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, John M.; Anderson, Heidi M. (2003). "Heyday of the gymnosperms: systematics and biodiversity of the Late Triassic Molteno fructifications". Strelitzia. 15: 1–308.

- ^ Barnard, P. D. W.; Long, A. G. (1973). "4.—On the Structure of a Petrified Stem and some Associated Seeds from the Lower Carboniferous Rocks of East Lothian, Scotland". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 69 (4): 91–108. doi:10.1017/S008045680001499X. ISSN 0080-4568. S2CID 129792299.

- ^ Barnard, P. D. W.; Long, A. G. (1975). "10.—Triradioxylon—a New Genus of Lower Carboniferous Petrified Stems and Petioles together with a Review of the Classification of Early Pterophytina". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 69 (10): 231–249. doi:10.1017/S0080456800015179. ISSN 0080-4568.

- ^ Anderson, John M.; Anderson, Heidi M.; Cleal, Chris J. (2007). "Brief history of the gymnosperms: classification, biodiversity, phytogeography and ecology" (PDF). Strelitzia. 20: 1–280.