Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cricket field

View on Wikipedia

|

|

|

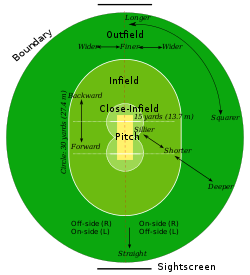

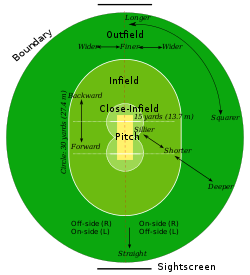

A cricket field or cricket oval is a large grass field on which the game of cricket is played. Although generally oval in shape, there is a wide variety within this: perfect circles, elongated ovals, rounded rectangles, or irregular shapes with little or no symmetry – but they will have smooth boundaries without sharp corners, almost without exception. There are no fixed dimensions for the field but its diameter usually varies between 450 and 500 feet (140 and 150 m) for men's cricket, and between 360 feet (110 m) and 420 feet (130 m) for women's cricket.

Cricket is unusual among major sports (along with golf, Australian rules football and baseball) in that there is no official rule for a fixed-shape ground for professional games. In some cases, fields are allowed to have even greater peculiarities, such as the 2.5m slope across the Lord's Cricket Ground, or the lime tree which sat inside the fence of the St Lawrence Ground.

On most grounds, a rope demarcates the perimeter of the field and is known as the boundary. Within the boundary and generally as close to the centre as possible will be the square which is an area of carefully prepared grass upon which cricket pitches can be prepared and marked for the matches. The pitch is where batsmen hit the bowled ball and run between the wickets to score runs, while the fielding team tries to return the ball to either wicket to prevent this.

Field size

[edit]The ICC Standard Playing Conditions define the minimum and maximum size of the playing surface for international matches. Law 19.1.3[1] of ICC Men's Test Match Playing Conditions as well as ICC Men's One Day International Playing Conditions states:

19.1.3 The aim shall be to maximise the size of the playing area at each venue. With respect to the size of the boundaries, no boundary shall be longer than 90 yards (82 metres), and no boundary should be shorter than 65 yards (59 metres) from the centre of the pitch to be used.

The equivalent ICC playing conditions (Law 19.1.3) for international women's cricket require the boundary to be between 60 and 70 yards (54.86 and 64.01 m) from the centre of the pitch to be used.[1]

In addition, the conditions require a minimum three-yard gap between the "rope" and the surrounding fencing or advertising boards. This allows players to dive without risk of injury.

The conditions contain a heritage clause, which exempts stadiums built before October 2007. However, most stadiums which regularly host international games easily meet the minimum dimensions.

A typical Test match stadium would be larger than these defined minimums, with over 20,000 sq yd (17,000 m2) of grass (having a straight boundary of about 80 m).[2] In contrast an association football field needs only about 9,000 sq yd (7,500 m2) of grass, and an Olympic stadium would contain 8,350 sq yd (6,980 m2) of grass within its 400m running track, making it difficult to play international cricket in stadiums not built for the purpose. Nevertheless, Stadium Australia which hosted the Sydney Olympics in 2000 had its running track turfed over with 30,000 seats removed to make it possible to play cricket there, at a cost of A$80 million.[3] This is one of the reasons cricket games generally cannot be hosted outside the traditional cricket-playing countries, and a few non-Test nations like Canada, the UAE and Kenya that have built Test standard stadiums.

Pitch

[edit]

Most of the action takes place in the centre of this ground, on a rectangular clay strip usually with short grass called the pitch. The pitch measures 22 yd (20.12 m) (1 chain) long.

At each end of the pitch three upright wooden stakes, called the stumps, are hammered into the ground. Two wooden crosspieces, known as the bails, sit in grooves atop the stumps, linking each to its neighbour. Each set of three stumps and two bails is collectively known as a wicket. One end of the pitch is designated the batting end where the batsman stands and the other is designated the bowling end where the bowler runs in to bowl. The area of the field on the side of the line joining the wickets where the batsman holds his bat (the right-hand side for a right-handed batsman, the left for a left-hander) is known as the off side, the other as the leg side or on side.

Lines drawn or painted on the pitch are known as creases. Creases are used to adjudicate the dismissals of batsmen, by indicating where the batsmen's grounds are, and to determine whether a delivery is fair.

Cricket pitches are usually oriented as close to the north–south direction as practical, because the low afternoon sun would be dangerous for a batter facing due west.[4] This means that some oval fields are oriented with their longer axes straight of the wicket, and others have their longer axes square of the wicket.

Parts of the field

[edit]For limited overs cricket matches, there are two additional field markings to define areas relating to fielding restrictions. The "circle" or "fielding circle" is an oval described by drawing a semicircle of 30 yards (27 m) radius from the centre of each wicket with respect to the breadth of the pitch and joining them with lines parallel, 30 yards (27 m) to the length of the pitch. This divides the field into an infield and outfield and can be marked by a painted line or evenly spaced discs. The close-infield is defined by a circle of radius 15 yards (14 m), centred at middle stump guard on the popping crease at the end of the wicket, and is often marked by dots.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Cricket Rules and Regulations | ICC Rules of Cricket". www.icc-cricket.com. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ "World Largest Flag: New World Record by VIP Flags (2004)". VIP Flags. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2025. A flag measuring 340 by 510 feet (110 yd × 170 yd; 100 m × 160 m) i.e. 173,400 square feet (19,270 sq yd; 16,110 m2) was unveiled at the National Stadium, Karachi. This video shows that the rectangular flag, when fully unfurled, comfortably fit within the playing area.

- ^ "CSA rules out cricket at FIFA World Cup venues | Cricket | ESPN Cricinfo". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ "Orientation of outdoor playing areas". Government of Western Australia, Department of Sport and Recreation. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.