Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cross-link

View on Wikipedia

In chemistry and biology, a cross-link is a bond or a short sequence of bonds that links one polymer chain to another. These links may take the form of covalent bonds or ionic bonds and the polymers can be either synthetic polymers or natural polymers (such as proteins).

In polymer chemistry "cross-linking" usually refers to the use of cross-links to promote a change in the polymers' physical properties.

When "crosslinking" is used in the biological field, it refers to the use of a probe to link proteins together to check for protein–protein interactions, as well as other creative cross-linking methodologies.[not verified in body]

Although the term is used to refer to the "linking of polymer chains" for both sciences, the extent of crosslinking and specificities of the crosslinking agents vary greatly.

Synthetic polymers

[edit]

Chemical reactions associated with crosslinking of drying oils, the process that produces linoleum.

Crosslinking generally involves covalent bonds that join two polymer chains. The term curing refers to the crosslinking of thermosetting resins, such as unsaturated polyester and epoxy resin, and the term vulcanization is characteristically used for rubbers.[1] When polymer chains are crosslinked, the material becomes more rigid. The mechanical properties of a polymer depend strongly on the cross-link density. Low cross-link densities increase the viscosities of polymer melts. Intermediate cross-link densities transform gummy polymers into materials that have elastomeric properties and potentially high strengths. Very high cross-link densities can cause materials to become very rigid or glassy, such as phenol-formaldehyde materials.[2]

In one implementation, unpolymerized or partially polymerized resin is treated with a crosslinking reagent. In vulcanization, sulfur is the cross-linking agent. Its introduction changes rubber to a more rigid, durable material associated with car and bike tires. This process is often called sulfur curing. In most cases, cross-linking is irreversible, and the resulting thermosetting material will degrade or burn if heated, without melting. Chemical covalent cross-links are stable mechanically and thermally. Therefore, cross-linked products like car tires cannot be recycled easily. [citation needed]

A class of polymers known as thermoplastic elastomers rely on physical cross-links in their microstructure to achieve stability, and are widely used in non-tire applications, such as snowmobile tracks, and catheters for medical use. They offer a much wider range of properties than conventional cross-linked elastomers because the domains that act as cross-links are reversible, so can be reformed by heat. The stabilizing domains may be non-crystalline (as in styrene-butadiene block copolymers) or crystalline as in thermoplastic copolyesters.

Alkyd enamels, the dominant type of commercial oil-based paint, cure by oxidative crosslinking after exposure to air.[4]

Physical cross-links

[edit]In contrast to chemical cross-links, physical cross-links are formed by weaker interactions. For example, sodium alginate gels upon exposure to calcium ions, which form ionic bonds that bridge between alginate chains.[5] Polyvinyl alcohol gels upon the addition of borax through hydrogen bonding between boric acid and the polymer's alcohol groups.[6][7] Other examples of materials which form physically cross-linked gels include gelatin, collagen, agarose, and agar agar.[citation needed]

Measuring degree of crosslinking

[edit]Crosslinking is often measured by swelling tests. The crosslinked sample is placed into a good solvent at a specific temperature, and either the change in mass or the change in volume is measured. The more crosslinking, the less swelling is attainable. Based on the degree of swelling, the Flory Interaction Parameter (which relates the solvent interaction with the sample), and the density of the solvent, the theoretical degree of crosslinking can be calculated according to Flory's Network Theory.[8]

Two ASTM standards are commonly used to describe the degree of crosslinking in thermoplastics. In ASTM D2765, the sample is weighed, then placed in a solvent for 24 hours, weighed again while swollen, then dried and weighed a final time.[9] The degree of swelling and the soluble portion can be calculated. In another ASTM standard, F2214, the sample is placed in an instrument that measures the height change in the sample, allowing the user to measure the volume change.[10] The crosslink density can then be calculated.

In biology

[edit]

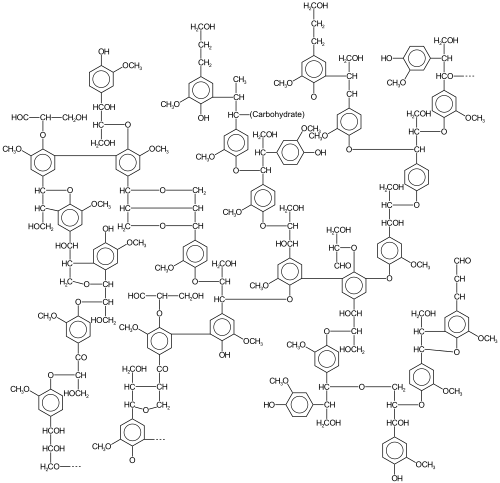

Lignin

[edit]Lignin is a highly crosslinked polymer that comprises the main structural material of higher plants. A hydrophobic material, it is derived from precursor monolignols. Heterogeneity arises from the diversity and degree of crosslinking between these lignols.[citation needed]

In DNA

[edit]

Intrastrand DNA crosslinks have strong effects on organisms because these lesions interfere with transcription and replication. These effects can be put to good use (addressing cancer) or they can be lethal to the host organism. The drug cisplatin functions by formation of intrastrand crosslinks in DNA.[11] Other crosslinking agents include mustard gas, mitomycin, and psoralen.[12]

Proteins

[edit]In proteins, crosslinks are important in generating mechanically stable structures such as hair and wool, skin, and cartilage. Disulfide bonds are common crosslinks.[13] Isopeptide bond formation is another type of protein crosslink.[citation needed]

The process of applying a permanent wave to hair involves the breaking and reformation of disulfide bonds. Typically a mercaptan such as ammonium thioglycolate is used for the breaking. Following this, the hair is curled and then "neutralized". The neutralizer is typically an acidic solution of hydrogen peroxide, which causes new disulfide bonds to form, thus permanently fixing the hair into its new configuration.[citation needed]

Compromised collagen in the cornea, a condition known as keratoconus, can be treated with clinical crosslinking.[14] In biological context crosslinking could play a role in atherosclerosis through advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which have been implicated to induce crosslinking of collagen, which may lead to vascular stiffening.[15]

Research

[edit]Proteins can also be cross-linked artificially using small-molecule crosslinkers. This approach has been used to elucidate protein–protein interactions.[16][17][18] Crosslinkers bind only surface residues in relatively close proximity in the native state. Common crosslinkers include the imidoester crosslinker dimethyl suberimidate, the N-Hydroxysuccinimide-ester crosslinker BS3 and formaldehyde. Each of these crosslinkers induces nucleophilic attack of the amino group of lysine and subsequent covalent bonding via the crosslinker. The zero-length carbodiimide crosslinker EDC functions by converting carboxyls into amine-reactive isourea intermediates that bind to lysine residues or other available primary amines. SMCC or its water-soluble analog, Sulfo-SMCC, is commonly used to prepare antibody-hapten conjugates for antibody development.[citation needed]

An in-vitro cross-linking method is PICUP (photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins).[19] Typical reagents are ammonium persulfate (APS), an electron acceptor, the photosensitizer tris-bipyridylruthenium (II) cation ([Ru(bpy)3]2+).[19] In in-vivo crosslinking of protein complexes, cells are grown with photoreactive diazirine analogs to leucine and methionine, which are incorporated into proteins. Upon exposure to ultraviolet light, the diazirines are activated and bind to interacting proteins that are within a few ångströms of the photo-reactive amino acid analog (UV cross-linking).[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hans Zweifel; Ralph D. Maier; Michael Schiller (2009). Plastics additives handbook (6th ed.). Munich: Hanser. p. 746. ISBN 978-3-446-40801-2.

- ^ Gent, Alan N. (1 April 2018). Engineering with Rubber: How to Design Rubber Components. Hanser. ISBN 978-1-56990-299-8. Retrieved 1 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pham, Ha Q.; Marks, Maurice J. (2012). "Epoxy Resins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_547.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Abraham, T.W.; Höfer, R. (2012), "Lipid-Based Polymer Building Blocks and Polymers", Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference, Elsevier, pp. 15–58, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53349-4.00253-3, ISBN 978-0-08-087862-1, retrieved 2022-06-27

- ^ Hecht, Hadas; Srebnik, Simcha (2016). "Structural Characterization of Sodium Alginate and Calcium Alginate". Biomacromolecules. 17 (6): 2160–2167. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00378. PMID 27177209.

- ^ "Experiments: PVA polymer slime". Education: Inspiring your teaching and learning. Royal Society of Chemistry. 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

A solution of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) can be made into a slime by adding borax solution, which creates cross-links between polymer chains.

- ^ Casassa, E.Z; Sarquis, A.M; Van Dyke, C.H (1986). "The gelation of polyvinyl alcohol with borax: A novel class participation experiment involving the preparation and properties of a "slime"". Journal of Chemical Education. 63 (1): 57. Bibcode:1986JChEd..63...57C. doi:10.1021/ed063p57.

- ^ Flory, P.J., "Principles of Polymer Chemistry" (1953)

- ^ "ASTM D2765 - 16 Standard Test Methods for Determination of Gel Content and Swell Ratio of Crosslinked Ethylene Plastics". www.astm.org. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "ASTM F2214 - 16 Standard Test Method for In Situ Determination of Network Parameters of Crosslinked Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE)". www.astm.org. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Siddik, Zahid H. (2003). "Cisplatin: Mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance". Oncogene. 22 (47): 7265–7279. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. PMID 14576837. S2CID 4350565.

- ^ Noll, David M.; Mason, Tracey Mcgregor; Miller, Paul S. (2006). "Formation and Repair of Interstrand Cross-Links in DNA". Chemical Reviews. 106 (2): 277–301. doi:10.1021/cr040478b. PMC 2505341. PMID 16464006.

- ^ Christoe, John R.; Denning, Ron J.; Evans, David J.; Huson, Mickey G.; Jones, Leslie N.; Lamb, Peter R.; Millington, Keith R.; Phillips, David G.; Pierlot, Anthony P.; Rippon, John A.; Russell, Ian M. (2005). "Wool". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.2315151214012107.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3.

- ^ Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 May;135(5):620-7.

- ^ Prasad, Anand; Bekker, Peter; Tsimikas, Sotirios (2012-08-01). "Advanced glycation end products and diabetic cardiovascular disease". Cardiology in Review. 20 (4): 177–183. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e318244e57c. ISSN 1538-4683. PMID 22314141. S2CID 8471652.

- ^ "Pierce Protein Biology - Thermo Fisher Scientific". www.piercenet.com. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Kou Qin; Chunmin Dong; Guangyu Wu; Nevin A Lambert (August 2011). "Inactive-state preassembly of Gq-coupled receptors and Gq heterotrimers". Nature Chemical Biology. 7 (11): 740–747. doi:10.1038/nchembio.642. PMC 3177959. PMID 21873996.

- ^ Mizsei, Réka; Li, Xiaolong; Chen, Wan-Na; Szabo, Monika; Wang, Jia-huai; Wagner, Gerhard; Reinherz, Ellis L.; Mallis, Robert J. (January 2021). "A general chemical crosslinking strategy for structural analyses of weakly interacting proteins applied to preTCR-pMHC complexes". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 296 100255. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100255. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 7948749. PMID 33837736.

- ^ a b Fancy, David A.; Kodadek, Thomas (1999-05-25). "Chemistry for the analysis of protein–protein interactions: Rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wavelength light". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (11): 6020–6024. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6020F. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6020. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 26828. PMID 10339534.

- ^ Suchanek, Monika; Anna Radzikowska; Christoph Thiele (April 2005). "Photo-leucine and photo-methionine allow identification of protein–protein interactions in living cells". Nature Methods. 2 (4): 261–268. doi:10.1038/nmeth752. PMID 15782218.