Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dan Ryan Expressway

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

Dan Ryan Expressway | |

|---|---|

| South Route Expressway | |

| Route information | |

| Maintained by IDOT | |

| Length | 11.47 mi[1] (18.46 km) |

| Existed | 1961–present |

| Component highways |

|

| Major junctions | |

| North end | |

| |

| South end | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Highway system | |

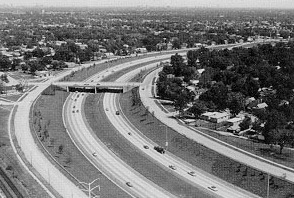

The Dan Ryan Expressway, often called "the Dan Ryan" by locals,[2] is an expressway in Chicago that runs from the Jane Byrne Interchange with Interstate 290 (I-290) near downtown Chicago through the South Side of the city. It is designated as both I-90 and I-94 south to 66th Street, a distance of 7.44 miles (11.97 km). South of 66th Street, the expressway meets the Chicago Skyway, which travels southeast; the I-90 designation transfers over to the Skyway, while the Dan Ryan Expressway retains the I-94 designation and continues south for 4.03 miles (6.49 km), ending at an interchange with I-57. This is a total distance of 11.47 miles (18.5 km).[1] The highway was named for Dan Ryan Jr., a former president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners.

Route description

[edit]On an average day, up to 307,100 vehicles use a portion of the Dan Ryan (2005 data).[1] The Dan Ryan, and its North Side counterpart the Kennedy Expressway, are the busiest roads in the entire state of Illinois. Utilizing an express-local system, the Dan Ryan has 14 lanes of traffic; seven in each direction, with four of those as express lanes and the other three providing access for exit and on-ramps. Because of its width, the Dan Ryan is very popular with commuters who live south of the Loop, making the road prone to traffic jams during weekday rush hour.

The posted directions on the Dan Ryan are different from the actual compass direction of the expressway, which may cause confusion to many travelers. The Dan Ryan for its entire 12-mile (19 km) length runs north–south. However, the Dan Ryan is a part of the larger Interstates 90 and 94, which both run east–west through the United States. Therefore, one who is traveling "west" on I-90/94 is actually driving north on the Dan Ryan as it passes through Chicago; I-90 continues northwest from the Kennedy split, while I-94 runs north–south until the Marquette Interchange in Milwaukee. Similarly, "east" on 90 and 94 on the entire system is really south through Chicago; the interstates will continue on an easterly path outside of the city. Chicagoans also typically refer to the direction of travel as either "inbound" or "outbound" from the downtown area.[citation needed]

Four miles of continuous high-rise housing projects (Stateway Gardens and the Robert Taylor Homes) formerly ran parallel to the expressway on its eastern side from Cermak Road south to Garfield Boulevard. However, nearly all of these buildings have been demolished as part of the CHA's transformation plan.[citation needed]

The Red Line runs in the median of the Dan Ryan south of 27th Street. This section of the Chicago "L" opened on September 28, 1969. Chicago pioneered the location of rapid transit line in expressway medians, a practice that has since been followed in several other cities, such as Toronto, and Pasadena.[3]

The control cities for the Dan Ryan Expressway are Indiana south, and the Chicago Loop northbound.[citation needed]

History

[edit]The first segment of the Dan Ryan, opened on December 12, 1961, and ran between US 12/US 20, 95th Street north to 71st Street in Chicago's Grand Crossing neighborhood. It was named after the recently deceased Dan Ryan, Jr., who was President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners who had worked to accelerate construction of Chicago-area expressways. A year later on December 15, 1962, the 8-mile (13 km) stretch of the Dan Ryan between 71st Street and I-90/Eisenhower Expressway (now signed as I-290) opened to the public as well as a 0.2-mile (0.32 km) stretch that connected it to the Bishop Ford Freeway (then known as the Calumet Expressway). During the planning stages it was also known as the South Route Expressway.[4]

In 1973 a elevated segment sank and was closed to traffic in May. A similar sinking occurred in 1966, according to Chicago Tribune archives.

In 1988–1989, the northern three miles (4.8 km) of the Dan Ryan, known as the Elevated Bridge, were completely reconstructed.[5]

In 2006 and 2007, the Illinois Department of Transportation reconstructed the entire length of the Dan Ryan Expressway, including the addition of a travel lane from 47th Street to 95th Street. The project was the largest expressway reconstruction plan in Chicago history. The total cost of the project was $975 million, nearly twice the $550 million original estimate for the project.[6][7]

Exit list

[edit]The entire route is in Chicago, Cook County.

| mi | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuation beyond I-290 | |||||

| 51.8 | 83.4 | 51H | No exit number westbound | ||

| 51.8 | 83.4 | 51I | Ida B. Wells Drive (500 South) | Signed as 51H eastbound | |

| 52.1 | 83.8 | 52A | Taylor Street (1000 South), Roosevelt Road (1200 South) | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 52.3 | 84.2 | 52B | Roosevelt Road (1200 South), Taylor Street (1000 South) | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 52.9 | 85.1 | 52C | 18th Street | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 53.0 | 85.3 | 53A | Canalport Avenue, Cermak Road (2200 South) | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 53.3 | 85.8 | 53 | Signed as exits 53B (south) and 53C (north) westbound | ||

| Western end of express lanes | |||||

| 53.8 | 86.6 | 53C | Cermak Road (2200 South) | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 54.7 | 88.0 | 54 | 31st Street (3100 South) | ||

| 55.2 | 88.8 | 55A | 35th Street | Rate Field, Illinois Institute of Technology | |

| 55.7 | 89.6 | 55B | Pershing Road (3900 South) | ||

| 56.2 | 90.4 | 56A | 43rd Street | ||

| 56.7 | 91.2 | 56B | 47th Street (4700 South) | ||

| 57.7 | 92.9 | 57 | Garfield Boulevard (5500 South) | ||

| 58.2 | 93.7 | 58A | 59th Street | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; signed as exit 58 westbound | |

| 58.7 | 94.5 | 58B | 63rd Street (6300 South) | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; signed as exit 58 eastbound | |

| 59.0 | 95.0 | 59A | Eastern end of I-90 concurrency; eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 59.3 | 95.4 | 59B | Marquette Road, 67th Street (6700 South) | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| Eastern end of express lanes | |||||

| 59.8 | 96.2 | 59C | 71st Street (7100 South) | ||

| 60.3 | 97.0 | 60A | 75th Street | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 60.4 | 97.2 | 60B | 76th Street | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 60.8 | 97.8 | 60C | 79th Street (7900 South) | ||

| 61.3 | 98.7 | 61A | 83rd Street | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 61.8 | 99.5 | 61B | 87th Street (8700 South) | ||

| 62.8 | 101.1 | 62 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 63.17 | 101.66 | 63 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| — | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Illinois Technology Transfer Center (2006). "T2 GIS Data". Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ Jindra, Sarah (August 17, 2022). "A crash course on the names of Chicago's expressways". WGN Television. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Thomas Buck (September 28, 1969). "Ryan rail service starts today". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Daniel Ryan (obituary)". Cook County Highways. April 1961. p. 3.

- ^ Hilkevitch, John (March 26, 2006). "Buckle up, it looks like a long ride". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 26, 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Haggerty, Ryan (October 26, 2007). "All lanes will be open on the Dan Ryan". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ^ Tridgell, Guy (October 18, 2007). "Falling gas prices won't stay". Daily Southtown. Retrieved October 25, 2007.[dead link]

External links

[edit]Dan Ryan Expressway

View on GrokipediaOverview

Naming and Significance

The Dan Ryan Expressway is named after Daniel B. Ryan Jr. (1894–1961), a Chicago businessman, lawyer, and politician who served as president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners from 1954 until his death in 1961, succeeding his father in that role.[7][8] As board president, Ryan Jr. was a strong advocate for infrastructure development, including the expansion of Chicago's highway system; he authored a 1955 bond issue that allocated millions of dollars toward expressway construction, accelerating projects like the Dan Ryan itself.[9] His contributions to public works, such as roads and parks, earned him recognition as a key figure in the region's post-World War II transportation growth.[10] Originally designated as the South Route during planning, the expressway was officially renamed the Dan Ryan Expressway in 1961, shortly after Ryan Jr.'s death on April 8, to honor his efforts in promoting the project.[3] This naming occurred amid the highway's opening phases, with full completion in 1962, and has since been upheld without major changes, though it faced a brief controversy in 2018 when a mayoral candidate proposed renaming it after Barack Obama, a suggestion that drew opposition from Ryan's family.[7] The expressway forms a critical segment of the Interstate Highway System, designated as both Interstate 90 (from the Jane Byrne Interchange southward) and Interstate 94 (continuing to the Indiana state line), with a total length of 11.47 miles (18.47 km).[11] It handles approximately 255,000 vehicles daily (as of 2025), establishing it as one of the busiest urban highways in the United States and the most congested corridor in the Chicago area.[12][13] Economically, the Dan Ryan facilitates essential commuter flows from Chicago's Loop to the southern suburbs while supporting freight movement along key industrial routes, bolstering regional connectivity and commerce.[3][14]Route Summary

The Dan Ryan Expressway runs north-south through Chicago's South Side as a major component of the Interstate Highway System, designated as both Interstate 90 (I-90) and Interstate 94 (I-94), with I-90 signed in an east-west direction despite the physical alignment. It originates at the Jane Byrne Interchange with I-290 (Eisenhower Expressway) near Roosevelt Road in downtown Chicago and proceeds southward for approximately 11.5 miles to its terminus at the interchange with I-57 near 95th Street.[15][11] The route divides into a northern section from the Jane Byrne Interchange to 47th Street, covering about 4 miles, and a southern section from 47th Street to I-57, spanning roughly 7.5 miles. This path generally follows a straight north-south corridor, transitioning through industrial zones near the lakefront, residential communities, and green spaces. Key landmarks along the way include the McCormick Place convention complex to the east in the early northern stretch, the Illinois Institute of Technology campus adjacent to the roadway around 33rd Street, and Washington Park to the west near 51st Street.[15][16] Southbound signage directs traffic toward Indiana Dunes as a control city, while northbound travelers see the Chicago Loop as the primary destination. The expressway employs an express-local lane configuration, with express lanes providing uninterrupted access for through traffic and local lanes serving interchanges for nearby areas.[17][18]Route and Infrastructure

Route Description

The Dan Ryan Expressway, designated as Interstate 90 and Interstate 94, commences at mile 0 at the Jane Byrne Interchange in downtown Chicago, where it connects with Interstate 290 and the Eisenhower Expressway, directing traffic southward through the densely urban South Side. From this starting point, the route initially traverses the Chinatown neighborhood near Cermak Road, characterized by high-rise developments and commercial activity, before crossing the South Branch of the Chicago River via fixed bridges with a 60-foot clearance that accommodate maritime traffic. Continuing south, it passes through Bronzeville around 31st Street, an area rich with historic architecture and revitalized residential zones, and integrates with local streets through a series of ramps allowing access to arterials like Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and State Street.[19][20] The expressway features a distinctive 14-lane configuration, with seven lanes in each direction divided into an express-local system: four express lanes for through traffic that bypass minor interchanges, and three local lanes providing direct access to exits for adjacent urban areas. The express lanes operate from south of 31st Street to north of 95th Street, providing through-traffic relief from local access points. This design facilitates efficient long-distance travel while serving neighborhood connectivity, with the roadway elevated or depressed through much of its length to weave between residential and commercial blocks. South of 51st Street, the surroundings maintain high urban density with tightly packed housing, parks like Washington Park, and institutions such as the University of Chicago nearby. The route culminates approximately 11.5 miles south at the 95th Street interchange (exit 62), where the express lanes end and it transitions to the Bishop Ford Memorial Freeway carrying I-94 southward toward the I-57 interchange near 119th Street, with the landscape shifting to more open, industrial, and suburban-like areas beyond 95th Street, including green spaces and single-family homes alongside freight rail corridors.[21][22][23] Current traffic patterns on the Dan Ryan reflect its role as a vital commuter corridor, with severe peak-hour congestion primarily northbound in the morning (7-9 a.m.) from the southern segments near 95th Street toward downtown, and southbound in the evening (4-6 p.m.) from the Jane Byrne Interchange. Post-2020 data indicates average speeds during these periods often drop to 20-30 mph in bottleneck zones around the I-55 (Stevenson Expressway) junction and 79th Street, contributing to an estimated 64 hours of annual delay for typical commuters on connected routes like the Stevenson-Dan Ryan segment. Overall, the expressway handles over 250,000 vehicles daily, with the express lanes helping to maintain through-traffic speeds around 45-55 mph outside peak times, though ongoing reconstruction efforts have intermittently exacerbated delays since 2021. The median also accommodates the Chicago Transit Authority's Red Line, briefly referenced here for its parallel integration aiding multimodal flow.[24][25][26]Interchanges and Exits

The Dan Ryan Expressway, as part of I-90 and I-94, utilizes milepost-based exit numbering consistent with Illinois Department of Transportation standards, beginning from the Indiana state line to maintain continuity across the interstate system.[27] Interchanges range from complex freeway-to-freeway connections to standard diamond configurations for local streets, with some featuring partial access restrictions to manage high traffic volumes. High-volume interchanges, such as those at 79th Street and 95th Street, serve as key distribution points for south side Chicago traffic, handling significant commuter and freight flows.[28] The following table lists the major interchanges from north to south, including exit numbers, primary destinations, approximate mile markers (where documented), and access notes.| Exit | Destinations | Mile Marker (approx.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51H-I | I-290 west / IL 110 (Eisenhower Expressway) / Congress Parkway | 51.0 | Full directional interchange; northern terminus at Jane Byrne Interchange; no direct access from I-290 to southbound locals in some configurations.[28] |

| 52A | Taylor Street / Roosevelt Road (IL 38) | 52.1 | Partial diamond interchange; eastbound exit and westbound entrance only for some ramps.[28] |

| 52C | 18th Street | 52.5 | Local access ramp; southbound exit and northbound entrance.[28] |

| 53 | I-55 (Stevenson Expressway) – St. Louis (south), Lake Shore Drive (north) | 53.3 | Complex wye interchange; signed as exits 53B (south) and 53C (north); major connection to southwest and lakeside routes.[28] |

| 54 | 31st Street | 54.0 | Diamond interchange; serves traffic to Chinatown and south side neighborhoods.[28] |

| 55A | 35th Street | 55.0 | Partial interchange; high local volume near University of Illinois Chicago.[28] |

| 55B | Pershing Road / 39th Street | 55.3 | Diamond interchange; connects to west side industrial areas.[28] |

| 56A | 43rd Street | 56.0 | Local ramp; northbound exit and southbound entrance.[28] |

| 56B | 47th Street | 56.2 | Partial access; serves Bronzeville district.[28] |

| 57 | Garfield Boulevard (55th Street) | 57.0 | Full diamond; major east-west connector for south side.[28] |

| 58B | 63rd Street | 58.5 | High-volume partial interchange; no southbound exit, northbound entrance only; links to Washington Park.[28] |

| 59C | 71st Street | 59.5 | Diamond interchange; access to Englewood community.[28] |

| 60A | South Lafayette Avenue / Halsted Street | 60.0 | Local access; combines with 79th Street ramps for efficiency.[28] |

| 60C | 79th Street | 60.3 | Major high-volume diamond interchange; partial restrictions on southbound to westbound; critical for Chatham and Auburn Gresham traffic distribution.[28] |

| 61A | 83rd Street | 61.0 | Partial interchange; serves Ashburn and Evergreen Park areas.[28] |

| 61B | 87th Street | 61.2 | Local ramp; connects to west side suburbs.[28] |

| 62 | 95th Street (US 12 / US 20) | 62.0 | Partial cloverleaf interchange at southern terminus; high-volume access to south suburbs; no direct southbound to eastbound in some lanes; transitions to Bishop Ford Memorial Freeway (I-94) southward.[28] |

History

Planning and Construction

The planning of the Dan Ryan Expressway originated as part of Chicago's 1940 city council-approved system of superhighways radiating from downtown, with the route formalized in the 1950s under Mayor Richard J. Daley's administration as a key component of the city's master plan for urban mobility.[29] The project gained momentum following the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which authorized federal funding for the Interstate Highway System and accelerated construction of urban expressways like the Dan Ryan, designated as part of I-90/I-94 to connect downtown Chicago with southern suburbs.[30] In 1956, the route was shifted eastward from the Chicago & Western Indiana Railroad alignment to follow the Rock Island Line at State Street, optimizing the path through the South Side while integrating with existing infrastructure.[29] Dan Ryan Jr., who served as Cook County Board president from 1954 to 1961, played a pivotal role in early advocacy for south-side infrastructure during the 1930s and 1940s, championing expanded roadways to address growing traffic and economic needs in the region.[29] As a longtime board member, Ryan pushed for comprehensive highway development, including the "South Route" concept that evolved into the Dan Ryan Expressway, and he directly engineered a 1955 Cook County bond issue that provided initial local funding to support planning and land acquisition efforts.[29] His efforts laid the groundwork for federal integration, ensuring the project aligned with national interstate goals under Daley's mayoralty, which began in 1955.[30] Construction began in the late 1950s, utilizing the abandoned Illinois & Michigan Canal right-of-way for much of the southern alignment to minimize urban disruption, and proceeded in phases to manage the complex build-out.[29] The initial segment opened on December 12, 1961, extending from 95th Street north to 71st Street in the Grand Crossing neighborhood, providing immediate relief to southern commuters.[29] Subsequent sections advanced northward, with the majority of the route—including connections to downtown—completed and opened to traffic by late 1962, marking the full 11.5-mile length from the Jane Byrne Interchange to 95th Street.[29] Engineering the expressway presented significant challenges due to its path through dense urban areas, requiring innovative solutions to navigate tightly packed neighborhoods, industrial zones, and extensive rail infrastructure.[29] The alignment skirted railroad embankments and yards near Union Station, necessitating elevated structures and coordinated clearances to avoid interfering with active freight and passenger rail operations while maintaining high-speed design standards.[29] These obstacles were addressed through phased earthwork and bridge construction, incorporating 34 bridges overall to span rail lines, streets, and the Chicago River.[30] The project was primarily funded through federal interstate dollars under the 1956 Act, which covered 90% of costs, supplemented by state matching funds and the 1955 county bond issue, at a total cost of approximately $180 million.[31] This financing model enabled rapid advancement, positioning the Dan Ryan as one of the largest urban interstate builds of the era and a cornerstone of Chicago's post-war transportation network.[30]Rehabilitations and Upgrades

The northern portion of the Dan Ryan Expressway underwent significant reconstruction between 1988 and 1989, focusing on the elevated section from the Circle Interchange southward to approximately 31st Street, with extensions addressing bridges up to 47th Street. This two-year project involved comprehensive resurfacing of the roadway and replacement of multiple bridges and piers to address deterioration from decades of heavy use, at a total cost of $210 million funded in part by a $49 million federal grant.[32][33][31] A more extensive full-length rehabilitation occurred from 2006 to 2007, encompassing the entire 11.5-mile corridor of the Dan Ryan Expressway at a cost of $975 million, marking one of the largest road construction projects in the nation's history at the time. The work included complete pavement replacement, upgrades to concrete barrier walls for enhanced safety, reconstruction of 15 flyover bridges, improvements to drainage and sewer systems, and the installation of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) such as electronic signage and traffic monitoring cameras to improve flow and incident response. During this project, several exit configurations were modified to optimize access, including adjustments to ramps near key interchanges like those at 63rd Street to better integrate with local roads and reduce congestion bottlenecks.[34][1] In the 2010s, subsequent upgrades targeted ancillary infrastructure, with investments in modernized lighting systems along the mainline and enhanced signage for better visibility and driver guidance as part of IDOT's multi-year improvement programs. These efforts, programmed at around $18.5 million for bridge, intersection, lighting, and engineering work through 2014, aimed to extend the lifespan of recent rehabilitations without major structural overhauls.[35] Into the 2020s, maintenance activities have emphasized routine preservation under the Rebuild Illinois initiative, including post-2020 pothole patching, bridge deck resurfacing, and minor drainage repairs, such as those at the Roosevelt Road interchange completed in phases through 2024. For instance, a 2024 project addressed patching and joint replacements on bridges over the Dan Ryan to mitigate wear from freeze-thaw cycles.[36] Looking ahead, as of 2025, the Illinois Department of Transportation is advancing studies for potential capacity enhancements, including feasibility assessments for widening segments to add managed lanes connecting to the I-55 Stevenson Expressway and integrating electric vehicle charging infrastructure under the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program. These efforts, outlined in IDOT's FY 2025-2030 Highway Improvement Program, also include ongoing bridge reconstructions, such as 36 structures and reversible lane access upgrades, to support future traffic demands and sustainability goals.[37][38][39]Design Features

Physical and Engineering Aspects

The Dan Ryan Expressway features a distinctive 14-lane cross-section in its northern section from 31st Street to 47th Street, comprising seven lanes in each direction, with the inner four lanes designated as express lanes for through traffic and the outer three as local lanes to facilitate entries and exits. South of 47th Street to the Chicago Skyway interchange, the configuration reduces to six lanes per direction (four express and two local), and south of the Skyway to 95th Street, it consists of four lanes per direction.[40][41] This configuration supports high-volume urban travel, with 12-foot-wide concrete lanes and 8- to 10-foot bituminous shoulders separated by a 20-foot median protected by double-faced steel guardrails.[40] The roadway employs continuously reinforced concrete pavement (CRCP) at a thickness of 13 inches, reinforced with 0.8% steel to accommodate extreme traffic loads exceeding 225,000 vehicles per day (as designed in 1988), including 14% trucks; current average annual daily traffic (AADT) exceeds 300,000 vehicles per day in peak sections as of 2023, ensuring durability under projected 20-year equivalent single axle loads of approximately 100 million in the heaviest lanes.[42][18] The express-local system optimizes traffic flow by segregating long-distance travelers on the inner express lanes from local access users on the outer lanes, with dedicated transfer roadways—typically two lanes wide—at key interchanges such as 45th Street, 49th Street, and 59th Street to shift vehicles between the two subsystems.[40] Acceleration and deceleration lanes, integrated at diamond interchanges spaced approximately every 0.5 miles, allow vehicles to merge or exit without disrupting mainline speeds, typically maintaining level tangents with minimal horizontal curvature to accommodate median and pavement transitions.[40] Steel girder bridges span local streets throughout the corridor, supporting the elevated sections and contributing to the overall structural integrity of this multi-level design.[18] Much of the expressway is constructed in a depressed profile to minimize urban disruption, though it transitions to an elevated structure at the northern end, rising approximately 60 feet above local roads, businesses, and railways.[1] This includes viaducts over the South Branch of the Chicago River, featuring a bascule bridge with a 170-foot horizontal clearance and 64.2-foot vertical clearance at low operating levels, designed to accommodate navigational needs while handling heavy vehicular loads.[43] South of 51st Street, the alignment incorporates slight grades to navigate terrain variations and integrate with adjacent infrastructure, maintaining overall flat alignment consistent with Chicago's topography.[40] Safety features include concrete Jersey barriers along the medians and edges, which were replaced during the 2007 reconstruction to enhance crash resistance and durability.[44] Overhead gantries supporting variable message signs were also installed as part of this rehabilitation, enabling real-time traffic advisories to improve operational efficiency on this high-speed corridor.[45] Engineering considerations for the expressway account for Chicago's low seismic risk, with bridge and pier designs emphasizing elastic response to minor ground motions per Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) standards, prioritizing ductility in connections to prevent brittle failure. Wind loads, influenced by the region's flat terrain and lake-effect weather patterns that amplify gusts and snow accumulation, are addressed through AASHTO-compliant specifications, including reinforced piers and girders to resist horizontal forces up to design speeds of 90-115 mph, ensuring stability across the 11.5-mile length.[46][47]Transit and Auxiliary Integration

The Dan Ryan Expressway integrates public transit through the Chicago Transit Authority's (CTA) Red Line, which features elevated tracks constructed in the highway's median from Cermak-Chinatown station near 18th Street to the 95th Street terminal.[48] This 9.4-mile branch opened for service in September 1969, providing parallel rapid transit access for south-side commuters and reducing reliance on single-occupancy vehicles.[48] Key stations embedded in the median, such as Sox-35th at 142 West 35th Street and 47th at 220 West 47th Street, offer elevated platforms with direct highway adjacency, facilitating seamless transfers for riders.[49][50] Auxiliary infrastructure supports bus and high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) access, particularly at southern interchanges. The 95th/Dan Ryan terminal functions as a primary connection point for Pace Suburban Bus routes, including the limited-stop 353 to Riverdale and Homewood, and the 395 to UPS Hodgkins via Interstate 294, enabling efficient suburban extensions from the expressway's end.[51][52] Park-and-ride facilities, such as the Homewood lot equipped with electric vehicle chargers and bus shelters, provide free parking for commuters accessing these Pace services that link back to the Dan Ryan corridor.[53] Shoulder lanes along segments of the expressway allow for bus priority operations, enhancing multimodal flow without dedicated HOV lanes.[54] Coordination with Metra commuter rail occurs at nearby stations, exemplified by the Sox-35th Red Line stop, which supports transfers to Metra Electric District services for regional connectivity.[55] The 59th Street Metra station on the Electric line, located adjacent to the expressway in Hyde Park, complements this integration by serving university and residential areas parallel to the Dan Ryan's path.[56] Emergency and maintenance facilities ensure operational reliability, with the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) maintaining a central response hub off the Dan Ryan Expressway in Chicago for incident management.[57] The IDOT Emergency Traffic Patrol covers the expressway 24/7, providing rapid assistance for breakdowns, including towing in designated zones to clear disruptions and restore traffic flow.[58] Future multimodal enhancements build on this framework through the CTA's Red Line Extension project, planned to add 5.5 miles of track from 95th Street to 130th Street, incorporating bike and pedestrian connections, bus interfaces, and expanded park-and-ride facilities at four new stations; however, as of November 2025, $2.1 billion in federal funding has been paused by the U.S. Department of Transportation, creating uncertainty for the project's timeline.[59][60] The Illinois FY 2025-2030 Highway and Multimodal Improvement Program allocates resources for regional transit upgrades, including potential electric vehicle charging infrastructure and bike/pedestrian paths near the Dan Ryan corridor to promote sustainable access.[39]Impact and Legacy

Social and Urban Effects

The construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway in the 1950s and 1960s displaced thousands of residents, more than half of whom were Black, primarily from low-income communities in neighborhoods such as Bronzeville and Woodlawn, as part of broader urban renewal efforts that disproportionately affected communities of color.[61][62] This displacement exacerbated existing inequities, with Black residents comprising 64% of those affected by expressway construction citywide despite representing only 23% of Chicago's population at the time.[62] The expressway's routing reinforced racial segregation by deliberately avoiding white-majority areas like Bridgeport—Mayor Richard J. Daley's home neighborhood—while carving through Black communities to the east, effectively creating a physical barrier between Bronzeville and white enclaves.[63] Urban planning analyses have critiqued this design as a tool to entrench racial divides, with the highway's path shifted eastward during planning to protect white residential zones while isolating Black neighborhoods.[64][20] Adjacent to the Dan Ryan, the Robert Taylor Homes public housing project—built in 1962 and housing over 27,000 low-income residents at its peak, mostly Black—was demolished between 1998 and 2007 as part of the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation.[65][66] This initiative replaced the high-rises with mixed-income developments, such as Legends South and Oakwood Shores, aiming to integrate affordable, market-rate, and public housing while promoting economic diversity, though it displaced thousands more and sparked debates over community disruption.[67][68] Over the long term, the expressway contributed to the economic isolation of Chicago's South Side by severing community ties, limiting pedestrian access to jobs and services north of the barrier, and fostering conditions that led to food deserts in affected areas.[69] These effects persisted, with South Side neighborhoods experiencing reduced opportunities for employment and healthy food access due to the highway's role in suburban commuter patterns that bypassed local economies.[70] Culturally, the Dan Ryan has been depicted as a stark divider in Chicago's urban narrative, often termed the "Dan Ryan Wall" in media and photography for its imposing concrete barriers that symbolize racial and socioeconomic separation; notable examples include Jay Wolke's 2005 photobook Along the Divide, which captures its isolating impact on the South Side landscape.[71]Safety, Environment, and Recent Developments

The Dan Ryan Expressway has a notable safety record marked by elevated crash rates, particularly in its urban segments, including the interchange at 79th Street. Contributing factors include heavy congestion, speeding, and recurrent wrong-way driving incidents, such as a 2021 head-on crash near 63rd Street that resulted in two fatalities and a 2023 wrong-way incident at 26th Street that killed one driver. The Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) addresses these risks through data-driven countermeasures, including expanded automated enforcement via cameras on expressways authorized under 2022 legislation to detect violations like red-light running at ramps and speed excesses. Overall crash data from IDOT indicates the Dan Ryan's involvement in a disproportionate share of urban interstate incidents pre-2020, with statewide reports underscoring the need for ongoing interventions. Environmentally, the expressway contributes to concentrated air pollution in adjacent South Side neighborhoods, where traffic emissions exacerbate respiratory issues like asthma through elevated levels of ultrafine particles and nitrogen oxides. Studies of near-roadway sampling sites confirm higher pollutant exposure for residents within 500 meters of the corridor, particularly affecting low-income communities. To mitigate noise impacts, IDOT installed noise barriers during the 2007-2012 reconstruction phase, covering segments from the Jane Byrne Interchange southward as part of a $111.4 million safety and environmental package. Stormwater management features, including improved drainage culverts and viaduct retrofits, have been integrated into recent projects to handle runoff and reduce flooding risks under the elevated structure, as seen in CREATE program enhancements along the 75th Street Corridor. Recent developments underscore persistent operational challenges amid rising post-pandemic traffic volumes, which averaged over 300,000 vehicles per day in 2024, approaching pre-COVID levels but straining the express-local system. A triple-fatal crash on November 2, 2025, at the I-57 split near 95th Street claimed the lives of a 12-year-old boy and two adults when their vehicle collided with another, closing southbound lanes for hours. Earlier, on September 29, 2025, gunfire near 63rd Street prompted a shutdown of outbound express lanes, disrupting morning commutes as Illinois State Police investigated bullet damage to a vehicle. IDOT's ongoing rehabilitation efforts, including 2025 bridge reconstructions at key overpasses like Ogden Avenue and pavement resurfacing, incorporate climate resilience measures such as elevated drainage to withstand extreme weather events projected under regional adaptation plans. Sustainability initiatives include LED lighting upgrades completed in 2022 along I-90/94 segments, reducing energy consumption and supporting broader carbon emission goals through efficient traffic management. Studies on managed lanes, like those extending from I-55 to the Dan Ryan, explore dynamic pricing to cut congestion-related emissions by up to 20% in high-volume scenarios as of 2025. Express lane usage has trended upward with post-reconstruction improvements, aiding flow during peak hours but requiring continued monitoring for equity in access.References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dan_Ryan_Expressway,_Chicago,_Illinois_(11045710854).jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dan_Ryan_Expressway_Near_Junction_with_Interstate_55_%2811051949284%29.jpg