Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

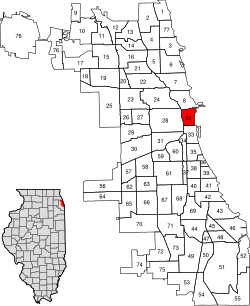

Chicago Loop

View on Wikipedia

The Loop is Chicago's central business district and one of the city's 77 municipally recognized community areas. Located at the center of downtown Chicago[3] on the shores of Lake Michigan, it is the second-largest business district in North America, after Midtown Manhattan in New York City. The world headquarters and regional offices of several global and national businesses, retail establishments, restaurants, hotels, museums, theaters, and libraries—as well as many of Chicago's most famous attractions—are located in the Loop.[4] The district also hosts Chicago's City Hall, the seat of Cook County, offices of the state of Illinois, United States federal offices, as well as several foreign consulates. The intersection of State Street and Madison Street in the Loop is the origin point for the address system on Chicago's street grid, a grid system that has been adopted by numerous cities worldwide.

Key Information

The Loop's definition and perceived boundaries have evolved over time. Since the 1920s, the area bounded by the Chicago River to the west and north, Lake Michigan to the east, and Roosevelt Road to the south has been called the Loop. It took its name from a somewhat smaller area, the 35 city blocks bounded on the north by Lake Street, on the west by Wells Street, on the south by Van Buren Street, and on the east by Wabash Avenue—the Union Loop formed by the 'L' in the late 1800s.[5] Similarly, the "South Loop" and the "West Loop" historically referred to areas within the Loop proper, but in the 21st century began to refer to the entire Near South and much of the Near West Sides of the city, respectively.[6][7]

In 1803, the United States Army built Fort Dearborn in what is now the Loop; although earlier settlement was present, this was the first settlement in the area sponsored by the United States federal government. When Chicago and Cook County were incorporated in the 1830s, the area was selected as the site of their respective seats. Originally mixed-use, the neighborhood became increasingly commercial in the 1870s. This process accelerated in the aftermath of the 1871 Great Chicago Fire, which destroyed most of the neighborhood's buildings. Some of the world's earliest skyscrapers were constructed in the Loop, giving rise to the Chicago School of architecture. By the late 19th century, cable car turnarounds and the Union Loop encircled the area, giving the neighborhood its name. Near the lake, Grant Park, known as "Chicago's front yard", is Chicago's oldest park; it was significantly expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and houses a number of features and museums. Starting in the 1920s, road improvements for highways were constructed to and into the Loop, perhaps most famously U.S. Route 66 (US 66), which was commissioned in 1926.

While dominated by offices and public buildings, its residential population boomed during the latter 20th century and first decades of the 21st, partly due to the development of former rail yards (at one time, the area had six major interurban railroad terminals and land was also needed for extensive rail cargo storage and transfer), industrial building conversions, as well as additional high-rise residences. Since 1950, the Loop's resident population has increased in percentage terms the most out of all of Chicago's community areas.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The origin of the name "the Loop" is disputed. Some sources claim it first referred to two cable car lines that used a circuit—constructed in 1882 and bounded by Van Buren Street, Wabash Avenue, Wells Street, and Lake Street—to enter and depart the downtown area.[8][9] Other research, however, has concluded that "the Loop" was not used as a proper noun until after the 1895–97 construction of the Union Loop used by 'L' trains, which shared the same route.[10]

19th century

[edit]In what is now the Loop, on the south bank of the Chicago River near today's Michigan Avenue Bridge, the United States Army erected Fort Dearborn in 1803, the first settlement in the area sponsored by the United States. When Chicago was initially platted in 1830 by the surveyor James Thompson, it included what is now the Loop north of Madison Street and west of State Street. The Sauganash Hotel, the first hotel in Chicago, was built in 1831 near Wolf Point at what is now the northwestern corner of the Loop. When Cook County was incorporated in 1831, the first meeting of its government was held at Fort Dearborn with two representatives from Chicago and one from Naperville. The entirety of what is now the Loop was part of the Town of Chicago when it was initially incorporated in 1833, except the Fort Dearborn reservation, which became part of the city in 1839, and land reclaimed from Lake Michigan.

The area was bustling by the end of the 1830s.[8] Lake Street started to become a center for retail at that time, until it was eclipsed by State Street in the 1850s.[8]

20th century

[edit]

By 1948 an estimated one million people came to and went from the Loop each day. Afterwards, suburbanization caused a decrease in the area's importance. Starting in the 1960s, however, the presence of an upscale shopping district caused the area's fortunes to increase.

21st century

[edit]The Loop's population has boomed in recent years, seeing a 158 percent population increase between 2000 and 2020.[2] Between 2010 and 2014, the number of jobs in the Loop increased by nearly 63,000, an increase of over 13%.[11]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 24,074 | — | |

| 1900 | 24,274 | 0.8% | |

| 1910 | 15,954 | −34.3% | |

| 1920 | 13,140 | −17.6% | |

| 1930 | 7,851 | −40.3% | |

| 1940 | 6,221 | −20.8% | |

| 1950 | 7,018 | 12.8% | |

| 1960 | 4,337 | −38.2% | |

| 1970 | 4,965 | 14.5% | |

| 1980 | 6,462 | 30.2% | |

| 1990 | 11,954 | 85.0% | |

| 2000 | 16,244 | 35.9% | |

| 2010 | 29,283 | 80.3% | |

| 2020 | 42,298 | 44.4% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 42,181 | −0.3% | |

| [2][12] | |||

Economy and employment

[edit]

The Loop, along with the rest of downtown Chicago, is the second-largest commercial business district in the United States, after New York City's Midtown Manhattan. Its financial district near LaSalle Street is home to United Airlines, Hyatt Hotels & Resorts, and CME Group's Chicago Board of Trade and Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

Aon Corporation maintains an office in the Aon Center.[13] Chase Tower houses the headquarters of Exelon.[14] United Airlines has its headquarters in Willis Tower, having moved its headquarters to Chicago from suburban Elk Grove Township in early 2007.[15] Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association has its headquarters in the Michigan Plaza complex.[16] Sidley Austin has an office in the Loop.[17]

The Chicago Loop Alliance is located at 55 West Monroe,[18] the Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce is located in an office in the Aon Center, the French-American Chamber of Commerce in Chicago has an office in 35 East Wacker, the Netherlands Chamber of Commerce in the United States is located in an office at 303 East Wacker Drive, and the US Mexico Chamber of Commerce Mid-America Chapter is located in an office in One Prudential Plaza.[19]

McDonald's was headquartered in the Loop until 1971, when it moved to suburban Oak Brook.[20] When Bank One Corporation existed, its headquarters were in the Bank One Plaza, which is now Chase Tower.[21] When Amoco existed, its headquarters were in the Amoco Building, which is now the Aon Center.[22]

In 2019, about 40 percent of Loop residents were also employed in the Loop.[23] 26.8 percent worked outside Chicago.[23] Respectively 11.5, 8.0, and 2.8 percent worked in the Near North Side, the Near West Side, and Hyde Park.[23] Conversely, 45.5 percent of the people employed in the Loop lived outside Chicago.[23] Lake View housed 4 percent of Loop employees, the highest of any of Chicago's community areas.[23] The Near North Side, West Town, and Lincoln Park respectively housed 3.8, 2.6, and 2.5 percent of those working in the Loop.[23]

The professional sector is the largest source of employment of both Loop residents and Loop employees, at respectively 21.4 and 23.3 percent.[23] Finance was the second-most-common employment for both groups, at respectively 13.5 and 17.7 percent.[23] Health Care was the third-largest sector for residents, at 10.2 percent, while Education was the third-largest sector for Loop employees, at 13 percent.[23] Education was the fourth-largest employer of residents, at 9.4 percent, while Public Administration was the fourth-largest for Loop employees, at 13 percent. Administration was the fifth-largest sector for both groups, at respectively 6.9 and 7.3 percent.[23]

Architecture

[edit]

The area has long been a hub for architecture. The vast majority of the area was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 but rebuilt quickly. In 1885 the Home Insurance Building, generally considered the world's first skyscraper, was constructed, followed by the development of the Chicago school, best exemplified by such buildings as the Rookery Building in 1888, the Monadnock Building in 1891, and the Sullivan Center in 1899.

Loop architecture has been dominated by skyscrapers and high-rises since early in its history. Notable buildings include the Home Insurance Building, considered the world's first skyscraper (demolished in 1931); the Chicago Board of Trade Building, a National Historic Landmark; and Willis Tower, the world's tallest building for nearly 25 years. Some of the historic buildings in this district were instrumental in the development of towers.

This area abounds in shopping opportunities, including the Loop Retail Historic District, although it competes with the more upscale Magnificent Mile area to the north. It includes Chicago's former Marshall Field's department store location in the Marshall Field and Company Building; the original Sullivan Center Carson Pirie Scott store location (closed February 21, 2007). Chicago's Downtown Theatre District is also found within this area, along with numerous restaurants and hotels.

Chicago has a famous skyline that features many of the world's tallest buildings as well as the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District. Chicago's skyline is spaced out throughout the downtown area. The Willis Tower, formerly known as the Sears Tower, the third-tallest building in the Western Hemisphere (and still second-tallest by roof height), stands in the western Loop in the heart of the city's financial district, along with other buildings, such as 311 South Wacker Drive and the AT&T Corporate Center.

Chicago's fourth-tallest building, the Aon Center, is located just south of Illinois Center. The complex is at the east end of the Loop, east of Michigan Avenue. Two Prudential Plaza is also located here, just to the west of the Aon Center.

The Loop contains a wealth of outdoor sculpture, including works by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Marc Chagall, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Alexander Calder, and Jean Dubuffet. Chicago's cultural heavyweights, such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Goodman Theatre, the Chicago Theatre, the Lyric Opera at the Civic Opera House building, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, are also in the area, as is the historic Palmer House Hilton hotel, found on East Monroe Street.

Chicago's waterfront, which is almost exclusively recreational beach and park areas from north to south, features Grant Park in the downtown area. Grant Park is the home of Buckingham Fountain, the Petrillo Music Shell, the Grant Park Symphony (where free concerts can be enjoyed throughout the summer), and Chicago's annual two-week food festival, the Taste of Chicago, where more than 3 million people try foods from over 70 vendors. The area also hosts the annual music festival Lollapalooza, which features popular alternative rock, heavy metal, EDM, hip hop, and punk rock artists. Millennium Park, which is a section of Grant Park, opened in the summer of 2004 and features Frank Gehry's Jay Pritzker Pavilion, Jaume Plensa's Crown Fountain, and Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate sculpture along Lake Michigan.

The Chicago River and its accompanying Chicago Riverwalk, which delineates the area, also provides entertainment and recreational opportunities, including the annual dyeing of the river green in honor of St. Patrick's Day. Trips down the Chicago River, including architectural tours by commercial boat operators, are favorites with locals and tourists alike.

Notable landmarks

[edit]

- Agora, a group of sculptures at the south end of Grant Park.[24]

- Art Institute of Chicago[25]

- Auditorium Building[26]

- Buckingham Fountain[27]

- Carbide & Carbon Building[26][28][29]

- Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building[26]

- Chicago Board of Trade Building[26]

- Chicago Theatre[26]

- Chicago Cultural Center[26]

- Chicago City Hall[26]

- Civic Opera House[26]

- Commercial National Bank Building[30]

- Field Building[26]

- Fine Arts Building[26]

- Grant Park[31]

- Jewelers Row District[26]

- Mather Tower[26]

- Historic Michigan Boulevard District[26]

- Monadnock Building[26]

- The Palmer House Hilton[26]

- Great Northern Hotel, Chicago[32]

- Printing House Row[26]

- Reliance Building[26]

- Rookery Building[26]

- Symphony Center – home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra[33]

- Willis Tower – formerly the Sears Tower

Government

[edit]The Loop is the seat of Chicago's city government. It is also the government seat of Cook County and houses an office for the governor of Illinois. The city and county governments are situated in the same century-old building. Across the street, the Richard J. Daley Center accommodates a sculpture by Pablo Picasso and the state law courts. Given its proximity to government offices, the center's plaza serves as a kind of town square for celebrations, protests, and other events.

The Loop is in South Chicago Township within Cook County.[34] Townships in Chicago were abolished for governmental purposes in 1902[35] but are still used for property assessment.[34]

The nearby James R. Thompson Center is the city headquarters for state government, with an office for the Governor. Many state agencies have offices here, including the Illinois State Board of Education.[36]

A few blocks away is the Everett McKinley Dirksen United States Courthouse, housing federal law courts and other federal government offices. It is the seat of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. The Kluczynski Federal Building is across the street. The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago is located on LaSalle Street in the heart of the financial district. The United States Postal Service operates the Loop Station Post Office at 211 South Clark Street.[37]

Fire Department

[edit]The Chicago Fire Department operates three fire stations in the Loop District:

- Engine Company 1, Aerial Tower Company 1, Ambulance 41 – 419 S. Wells St. – South Loop

- Engine Company 5, Truck Company 2, Special Operations Battalion Chief 5-1-5, Collapse Unit 5-2-1 – 324 S. Des Plaines St. – West Loop/Near West Side

- Engine Company 13, Truck Company 6, Ambulance 74, Battalion Chief 1, Marine and Dive Operations: Training Officer 6-8-5, District Chief: Marine and Dive Operations 6-8-6, SCUBA Team 6-8-7 – 259 N. Columbus Dr. – East Loop/Near East Side

Diplomatic missions

[edit]Several countries maintain consulates in the Loop. They include Argentina,[38] Australia,[39] Canada,[40] Costa Rica,[41] the Czech Republic,[42] Ecuador,[43] El Salvador,[44] France,[45] Guatemala,[46] Haiti,[47] Hungary,[48] Indonesia,[49] Israel,[50] the Republic of Macedonia,[51] the Netherlands,[52] Pakistan,[53] Peru,[54] the Philippines,[55] South Africa,[56] Turkey,[57] and Venezuela.[58] In addition, the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office of the Republic of China is in the Loop.[59]

Politics

[edit]Local

[edit]The Loop is currently part of the 4th, 25th, 34th, and 42nd wards of the Chicago City Council, which are represented by aldermen Sophia King, Byron Sigcho-Lopez, Bill Conway and Brendan Reilly.[60]

From the city's incorporation and division into wards in 1837 to 1992, the Loop as currently defined was at least partially contained within the 1st ward.[61] From 1891 to 1992 it was entirely within the 1st ward and was coterminous with it between 1891 and 1901.[62] It was while part of the 1st ward that it was represented by the Gray Wolves. The area has not had a Republican alderman since Francis P. Gleason served alongside Coughlin from 1895 to 1897.[63] (Prior to 1923, each ward elected two aldermen in staggered two-year terms.)[63]

| Period | 1st Ward | 2nd Ward | 42nd Ward | 4th Ward | 25th Ward |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923–1938 | John Coughlin, Democratic | Not in ward | Not in ward | Not in ward | Not in ward |

| 1938–1939 | Vacant | ||||

| 1939–1943 | Michael Kenna, Democratic | ||||

| 1943–1951 | John Budinger, Democratic | ||||

| 1951–1963 | John D'Arco Sr., Democratic | ||||

| 1963 | Michael Fiorito, Democratic | ||||

| 1963 | Vacant | ||||

| 1963–1968 | Donald Parrillo, Democratic | ||||

| 1968–1993 | Fred Roti, Democratic | ||||

| 1993–2007 | Not in ward | Madeline Haithcock, Democratic | Burton Natarus, Democratic | ||

| 2007–2015 | Robert Fioretti, Democratic | Brendan Reilly, Democratic | |||

| 2015–2019 | Not in ward | Sophia King, Democratic | Daniel Solis, Democratic | ||

| 2019–present | Byron Sigcho-Lopez, Independent |

In the Cook County Board of Commissioners the eastern half of the area is part of the 3rd district, represented by Democrat Jerry Butler, while the western half is part of the 2nd district, represented by Democrat Dennis Deer.[68]

State

[edit]In the Illinois House of Representatives, the community area is roughly evenly split lengthwise between, from east to west, Districts 26, 5, and 6, represented respectively by Democrats Kambium Buckner, Lamont Robinson, and Sonya Harper, with a minuscule portion in District 9 represented by Democrat Lakesia Collins.[69]

In the Illinois Senate most of the community area is in District 3, represented by Democrat Mattie Hunter, while a large part in the east is part of District 13, represented by Democrat Robert Peters, and a very small part in the west is part of District 5, represented by Democrat Patricia Van Pelt.[70]

Federal

[edit]The Loop community area has supported the Democratic Party in the past two presidential elections by large margins. In the 2016 presidential election, Loop residents cast 11,141 votes for Hillary Clinton and 2,148 votes for Donald Trump (79.43% to 15.31%).[71] In the 2012 presidential election, Loop residents cast 8,134 votes for Barack Obama and 2,850 votes for Mitt Romney (72.26% to 25.32%).[72]

In the U.S. House of Representatives, the area is wholly within Illinois's 7th congressional district, which is the most Democratically leaning district in Illinois, according to the Cook Partisan Voting Index, with a score of D+38, and represented by Democrat Danny K. Davis.

List of United States representatives representing the Loop since 1903[73]

Illinois's 1st congressional district (1903 – 1963):

- Martin Emerich, Democratic (March 4, 1903 – March 3, 1905)

- Martin B. Madden, Republican (March 4, 1905 – April 27, 1928)

- Vacant (April 27, 1928 – March 3, 1929)

- Oscar Stanton De Priest, Republican (March 4, 1929 – January 3, 1935)

- Arthur W. Mitchell, Democratic (January 3, 1935 – January 3, 1943)

- William L. Dawson, Democratic (January 3, 1943 – January 3, 1963)

Illinois's 7th congressional district (1963–present):

- Roland V. Libonati, Democratic (January 3, 1963 – January 3, 1965)

- Frank Annunzio, Democratic (January 3, 1965 – January 3, 1973)

- Vacant (January 3 – June 5, 1973)

- Cardiss Collins, Democratic (June 5, 1973 – January 3, 1997)

- Danny K. Davis, Democratic (January 3, 1997 – present)

Transportation

[edit]

The Loop area derives its name from transportation networks present in it.

Public transportation

[edit]Passenger lines reached seven Loop-area stations by the 1890s, with transfers from one to the other being a major business for taxi drivers prior to the advent of Amtrak in the 1970s and the majority of trains being concentrated at Chicago Union Station across the river in the Near West Side. The construction of a streetcar loop in 1882 and the elevated railway loop in the 1890s gave the area its name and cemented its dominance in the city.

In Metra the Millennium Station, which serves as the Chicago terminal of the Metra Electric District line that goes to University Park, and LaSalle Street Station, which serves as the Chicago terminal of the Rock Island District line bound for Joliet, are in the Loop.[74] In addition to the terminals, the Van Buren Street station and Museum Campus/11th Street station on the Electric District line are also in the Loop.[74] All stations in the Loop are in Zone A for fare collection purposes.[74] The interurban South Shore Line, which goes to South Bend, Indiana, has its Chicago terminal at Millennium Station.

All lines of the Chicago "L" except the Yellow Line serve the Loop area for at least some hours. The State Street Subway and Dearborn Street Subway, respectively parts of the Red Line and Blue Line, are present in the Loop area and offer 24/7 service; the Red and Blue Lines are the only rapid transit lines in the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains to offer such service. Bus Rapid Transit has been implemented in the Loop.

Private transportation and roads

[edit]

Chicago's address system has been standardized as beginning at the intersection of State and Madison Streets since September 1, 1909.[75] Prior to that time, Chicago's street system was a hodgepodge of various systems which had resulted from the different municipalities that Chicago annexed in the late 19th century.[75] The implementation of the new street system was delayed by two years in the Loop to allow businesses more time to acclimate to their new addresses.[75]

Several streets in the Loop have multiple levels, some as many as three. The most prominent of these is Wacker Drive, which faces the Chicago River throughout the area. Illinois Center neighborhood has three-level streets.

The eastern terminus of US 66, an iconic highway in the United States first charted in 1926,[76] was located at Jackson Boulevard and Michigan Avenue.[77] When Illinois and Missouri agreed that the local signage for US 66 should be replaced with that of Interstate 55 (I-55) as the highway was predominately north–south in those states,[a] most signs of the former highway in Chicago were removed without incident but the final sign on the corner of Jackson and Michigan was removed with great fanfare on January 13, 1977, and replaced with a sign reading "END OF ROUTE 66".[78]

The first anti-parking ordinance of streets in the Loop was passed on May 1, 1918, in order to help streetcars, and had been advocated by Chicago Surface Lines.[79] This law banned the parking of any vehicle between 7 and 10 a.m. and 4 and 7 p.m. on a street used by streetcars; approximately 1,000 violators of this law were arrested in the first month of the ordinance's enforcement.[80] The La Salle Hotel's parking garage was the first high-rise parking garage in the Loop, constructed in 1917 at the corner of Washington and LaSalle Streets[81] and remaining in service until its demolition in 2005.[82] In the 1920s old buildings were purchased in the area and converted to parking structures.[81] More high-rise garages and parking lots were constructed in the 1930s, which also saw the advent of double-deck parking.[81] The first parking meters were installed in 1947 and private garages were regulated in 1957; they were banned outright in the Loop in the 1970s in response to federal air-quality standards.[81] The first underground garages were built by the city in the early 1950s.[81]

All residences and places of employment within the Loop are in highly walkable areas;[83] the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning defines such areas based on population density, the length of city blocks, tree canopy cover, fatalities or grievous injuries incurred by pedestrians and bicyclists in the area, the density of intersections, and amenities located near the area.[84] 33.3 percent of Loop residents walk or bike to work compared to 7.3 percent citywide.[85] An additional 19.4 percent of Loop residents use transit for a daily commute, while 23.4 percent of residents citywide do.[85] Just 22.2 percent of Loop residents drive to work alone or in a carpool, compared to 54.9 percent of all Chicago residents and 72.5 percent in the greater Chicago region.[85] By household, 47.2 percent of Loop residents do not have access to a personal vehicle at all, compared to 26.4 percent citywide and 12.6 percent regionally.[85]

Geography and neighborhoods

[edit]The Loop is Community Area 32.[8] In addition to the financial (West Loop–LaSalle Street Historic District), theatre, and jewelry (Jewelers Row District) districts, there are neighborhoods that are also part of the Loop community area.

New Eastside

[edit]

According to the 2010 census, 29,283 people live in the neighborhoods in or near the Loop. The median sale price for residential real estate was $710,000 in 2005 according to Forbes.[86] In addition to the government, financial, theatre and shopping districts, there are neighborhoods that are also part of the Loop community area. For much of its history this Section was used for Illinois Central rail yards, including the IC's Great Central Station, with commercial buildings along Michigan Avenue. The New Eastside is a mixed-use district bordered by Michigan Avenue to the west, the Chicago River to the north, Randolph Street to the south, and Lake Shore Drive to the east. It encompasses the entire Illinois Center and Lakeshore East[87] is the latest lead-developer of the 1969 Planned Development #70, as well as separate developments like Aon Center, Prudential Plaza, Park Millennium Condominium Building, Hyatt Regency Chicago, and the Fairmont Chicago, Millennium Park. The area has a triple-level street system and is bisected by Columbus Drive. Most of this district has been developed on land that was originally water and once used by the Illinois Central Railroad rail yards. The early buildings in this district such as the Aon Center and One Prudential Plaza used airspace rights in order to build above the railyards. The New Eastside Association of Residents (NEAR) has been the recognized community representative (Illinois non-profit corporation) since 1991 and is a 501(c)(3) IRS tax-exempt organization.

The triple-level street system allows for trucks to mainly travel and make deliveries on the lower levels, keeping traffic to a minimum on the upper levels. Through north–south traffic uses Middle Columbus and the bridge over the Chicago River. East–west through traffic uses either Middle Randolph or Upper and Middle Wacker between Michigan Avenue and Lake Shore Drive.

Printer's Row

[edit]Printer's Row, also known as Printing House Row, is a neighborhood located in the southern portion of the Loop community area of Chicago. It is centered on Dearborn Street from Ida B. Wells Drive on the north to Polk Street on the south, and includes buildings along Plymouth Court on the east and Federal Street to the west. Most of the buildings in this area were built between 1886 and 1915 for house printing, publishing, and related businesses. Today, the buildings have mainly been converted into residential lofts. Part of Printer's Row is an official landmark district, called the Printing House Row District.[88] The annual Printers Row Lit Fest is held in early June along Dearborn Street.[89]

South Loop

[edit]Most of the area south of Ida B. Wells Drive between Lake Michigan and the Chicago River, excepting Chinatown, is referred to as the South Loop. Perceptions of the southern boundary of the neighborhood have changed as development spread south, and the name is now used as far south as 26th Street.

The neighborhood includes former railyards that have been redeveloped as new-town-in-town such as Dearborn Park and Central Station. Former warehouses and factory lofts have been converted to residential buildings, while new townhouses and highrises have been developed on vacant or underused land. Dearborn Station at the south end of Printers Row, is the oldest train station still standing in Chicago; it has been converted to retail and office space. A major landowner in the South Loop is Columbia College Chicago, a private school that owns 17 buildings.

South Loop is zoned to the following Chicago Schools: South Loop School and Phillips Academy High School. Jones College Prep High School, which is a selective enrollment prep school drawing students from the entire city, is also located in the South Loop.

The South Loop was historically home to vice districts, including the brothels, bars, burlesque theaters, and arcades. Inexpensive residential hotels on Van Buren and State Street made it one of the city's Skid Rows until the 1970s. One of the largest homeless shelters in the city, the Pacific Garden Mission, was located at State and Balbo from 1923 to 2007, when it moved to 1458 S. Canal St.

Historic Michigan Boulevard District

[edit]The Loop also contains the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District, which is the section of Michigan Avenue opposite Grant Park and Millennium Park.

Historical images and current architecture of the Chicago Loop can be found in Explore Chicago Collections, a digital repository made available by Chicago Collections archives, libraries and other cultural institutions in the city.[90]

Loop Retail Historic District

[edit]The Loop Retail Historic District is a shopping district within the Chicago Loop community area in Cook County, Illinois, United States. It is bounded by Lake Street to the north, Ida B. Wells Drive to the south, State Street to the west and Wabash Avenue to the east. The district has the highest density of National Historic Landmark, National Register of Historic Places and Chicago Landmark designated buildings in Chicago. It hosts several historic buildings including former department store flagship locations Marshall Field and Company Building (now Macy's at State Street), and the Sullivan Center (formerly Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building).

Education

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]Columbia College Chicago and Roosevelt University are all located in the Loop. DePaul University also has a campus in the Loop. The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and University of Notre Dame run their EMBA programs in their Chicago Campuses in the Loop.

National-Louis University is located in the historic Peoples Gas Building on Michigan Avenue across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the nation's largest independent schools of art and design, is headquartered in Grant Park.

Harold Washington College is a City Colleges of Chicago community college located in the Loop. Adler School of Professional Psychology is a college located in the Loop. Argosy University has its head offices on the thirteenth floor of 205 North Michigan Avenue in Michigan Plaza.[91][92] Harrington College of Design is located at 200 West Madison Street after relocating from the Merchandise Mart.[93] Trinity Christian College offers an accelerated teaching certification program at 1550 S. State Street in the South Loop.

Spertus Institute, a center for Jewish learning & culture, is located at 610 S. Michigan Ave. Graduate level courses (Master and Doctorate) are offered in Jewish Studies, Jewish Professional Studies and Non-profit Management. Located at 180 North Wabash Avenue is Meadville Lombard Theological School which is affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association, a liberal, progressive seminary offering graduate-level theological and ministerial training. East-West University is located at 816 S Michigan Ave.

Primary and secondary schools

[edit]Chicago Public Schools serves residents of the Loop. Some residents are zoned to the South Loop School, while some are zoned to the Ogden International School for grades K-8.[94] Some residents are zoned to Phillips Academy High School, while others are zoned to Wells Community Academy High School.[95] Any graduate from Ogden's 8th grade program may automatically move on to the 9th grade at Ogden, but students who did not graduate from Ogden's middle school must apply to the high school.[96]

Jones College Prep High School, a public selective enrollment school, is also located here.

Muchin College Prep, a Noble Network of Charter Schools, is also located here, in the heart of Chicago on State Street.

Private schools:

Parks and recreation

[edit]The Loop has several parks.

Chicago Riverwalk

[edit]The Chicago Riverwalk spans the southern edge of the Chicago River.

Grant Park

[edit]Grant Park is located on the shores of Lake Michigan. Set aside in the late 19th century, it was originally known as "Lake Park" but was renamed for Civil War general and U.S. President Ulysses Grant. Buckingham Fountain was constructed in 1927 in Grant Park.

Maggie Daley Park

[edit]Maggie Daley Park is located to the east of Millennium Park.

Millennium Park

[edit]Millennium Park is located northwest of Grant Park. Originally intended to celebrate the new millennium, it opened in 2004.

Printer's Row Park

[edit]Officially known as Park No. 543, this park is located in the Printer's Row neighborhood.[97] It contains a community garden and an ornamental fountain.[97]

Pritzker Park

[edit]Pritzker Park is located on State Street[98] near Harold Washington Library. It occupies the site of the Rialto Hotel, which was demolished in 1990.[98] It is a green space developed by Ronald Jones and named for Cindy Pritzker.[98] Originally constructed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, the Chicago Park District assumed control of it in 2008.[98] It has a short wall with quotes from famous writers and philosophers.[98]

Theodore Roosevelt Park

[edit]Theodore Roosevelt Park is located in the South Loop.[99] Named for U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, it was constructed beginning in 1980 as an adjunct to the Dearborn Park homes.[99] It contains open space and three tennis courts.[99] It is located on Roosevelt Road, also named for Roosevelt.[99]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It is standard practice in the United States, both with U. S. Routes and Interstates, to number north-south roads with odd numbers and east-west roads with even numbers.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Chicago Loop". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. January 15, 1980.

- ^ a b c d e f "Community Data Snapshot - Loop" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ "The Loop". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ "Top Ten Largest CBDs in the USA". Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "The Loop". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Matthews, David (August 25, 2015). "Where Does The South Loop Start and End? Borders a Work in Progress". Block Club Chicago. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Harrington, Adam (June 14, 2023). "What is the Loop in Chicago?". CBS News Chicago. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Danzer, Gerald A. "The Loop". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Thompson, Joe. "Cable Car Lines in Chicago". The Cable Car Home Page. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Reardon, Patrick T. (July 26, 2004). "It all starts downtown". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "Downtown jobs hit a record high". chicagobusiness.com. Crains. November 28, 2014. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Paral, Rob. "Chicago Community Areas Historical Data". Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ "Office Location Search Results". Aon Corporation. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Contact Us". Exelon. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Illinois Gov. Rod R. Blagojevich and Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley Welcome Chicago's Hometown Airline". United Airlines. July 15, 2006. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us". Blue Cross Blue Shield. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Chicago". Sidley Austin. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Chicago Loop Alliance". Choose Chicago. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Chicago". SkyTeam. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ Cross, Robert. "Inside Hamburger Central Archived August 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine." Chicago Tribune. January 9, 1972. G18. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Information." Bank One Corporation. April 10, 2001. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "Contacts." Amoco. February 12, 1998. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j CMAP, p. 9

- ^ "City of Chicago :: Agora". www.cityofchicago.org. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Roberta Smith (May 13, 2009). "A Grand and Intimate Modern Art Trove". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Chicago Landmarks - Alphabetical List". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Noreen S. Ahmed-Ullah (July 16, 2008). "Buckingham Fountain's $25 million renovation to begin after Labor Day". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ "A toast to the skyline". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. November 16, 2007. pp. 2:3.

- ^ Wolfe, Gerard R. (1996). Chicago: In and Around the Loop. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 210. ISBN 0-07-071390-1.

- ^ Commission on Chicago Landmarks (April 7, 2016). Landmark Designation Report: Commercial National Bank Building (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

The Commercial National Bank Building is the oldest surviving example of a high-rise commercial bank building in Chicago designed by D. H. Burnham & Company, one of the most significant architectural firms in Chicago during the late 19th and early 20th century.

- ^ Liza Kaufman Hogan (November 5, 2008). "Chicago's Grant Park turns into jubilation park". CNN. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ^ "Marshal Field Estate Will Demolish Great Northern Hotel". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. January 14, 1940. p. 36. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ "About". Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "What Cook County Township Am I In?". Kensington Research. Kensington Research and Recovery. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Cook County Township Government FAQ Part 1". The Civic Federation. April 14, 2010. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Home page". Illinois State Board of Education. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ "Post Office Location – LOOP". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ "Argentine Consulates in the United States". Consulate-General of Argentina in New York. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Australian Consulate-General in Chicago, United States of America". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on January 1, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us". Consulate-General of Canada in Chicago. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Consulates in the United States". Embassy of Costa Rica Washington, DC. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Czech criminal history record". Consulate-General of the Czech Republic in Chicago. Retrieved January 31, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Other Consulates in the USA". Consulate-General of Ecuador in Chicago. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Norte América". Consulate-General of El Salvador in Miami. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Address and Hours of operation". Consulate-General of France in Chicago. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Home page". Consulate-General of Guatemala in Chicago. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to the Consulate General of the Republic of Haiti in Chicago". Consulate-General of Haiti in Chicago. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Consulate General of Hungary Chicago". Consulate General of Hungary Chicago. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Home page". Consulate-General of Indonesia in Chicago. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "General info: Mission Location". Consulate-General of Israel in Chicago. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Diplomatic missions" (in Macedonian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Macedonia. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "Home page". Consulate-General of the Netherlands in Chicago. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Consulate General of The Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Chicago USA". Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Jurisdicciones Consulares en USA". Consulate-General of Peru in Chicago. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us". Consulate-General of the Philippines in Chicago. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Other Missions". Consulate-General of South Africa in New York. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Contact". Embassy of Turkey in Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Home page". Consulate-General of Venezuela in Chicago. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Home". Taipei Economic and Cultural Office Chicago. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Aldermanic Wards for the City of Chicago" (PDF). City of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ "Ward Map - 11 February 1837". Chicagology. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "1900 Chicago City Ward Map". A Look at Cook. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Centennial List of Mayors, City Clerks, City Attorneys, City Treasurers, and Aldermen, elected by the people of the city of Chicago, from the incorporation of the city on March 4, 1837 to March 4, 1937, arranged in alphabetical order, showing the years during which each official held office". Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "A LOOK AT COOK". A Look at Cook. Archived from the original on August 18, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "Some Chicago GIS Data". University of Chicago Library. University of Chicago. March 18, 2015. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ Germuska, Joe; Boyer, Brian. "The old and new ward maps, side-by-side -- Chicago Tribune". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 4, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dawson, Michael. "Chicago Democracy Project - Welcome!". Chicago Democracy Project. University of Chicago. Archived from the original on December 8, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "Cook County Commissioner District Map | Cook County Open Data". Cook County Government Open Data. Cook County. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Illinois House". Illinois Policy. April 20, 2016. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "Illinois Senate". Illinois Policy. April 20, 2016. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2016). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2016 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2012). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2012 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Congressional District Shapefiles". UCLA. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c "System Map". Metra. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Bentley, Chris (May 20, 2015). "The guy who made it easy to navigate Chicago". WBEZ Chicago. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Teague, p. 88

- ^ Teague, p. 2

- ^ Teague, pp. 2–3

- ^ Lind, p. 200

- ^ Lind, pp. 200–201

- ^ a b c d e Mabwa, Nasutsa M. "Parking". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Francisco, Jamie (April 1, 2005). "Hailed for its innovation, but razed as out-of-date". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ CMAP, p. 10

- ^ "Population and Jobs in Highly Walkable Areas". Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d CMAP, p. 8

- ^ "Elements of Urbanism: Chicago". Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ "Lakeshore East Map". Archived from the original on July 25, 2006.

- ^ "Printing House Row District". Chicago Landmarks. City of Chicago. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ "Printers Row Lit Fest". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ Long, Elizabeth. "A Single Portal to Chicago's History". The University of Chicago News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ Baeb, Eddie (November 14, 2007). "School moving Chicago campus, HQ to Michigan Avenue". Chicago Business News. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Argosy University, Chicago Campus 2nd Semester Summer Classes Start Today at New Location on Michigan Avenue". Fox Business. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "History of Our Design School". Interiordesign.edu. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Near North/West/Central Elementary Schools Archived June 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine" (Archive). Chicago Public Schools. May 17, 2013. Retrieved on May 25, 2015.

- ^ "West/Central/South High Schools" (). Chicago Public Schools. May 17, 2013. Retrieved on May 25, 2015.

- ^ "Admissions". Ogden International School. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

Graduates of 8th grade at Jenner Campus can automatically enroll in 9th grade at Ogden's West Campus. If your child graduated from a different middle school [...]

- ^ a b "Park No. 543". Chicago Park District. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Pritzker Park". Chicago Park District. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Roosevelt (Theodore) Park". Chicago Park District. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Community Data Snapshot - The Loop" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. June 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- Lind, Alan R. (1974). Chicago Surface Lines: An Illustrated History. Park Forest, Illinois: Transport History Press.

- Teague, Tom (1991). Searching for 66. Springfield, Illinois: Samizdat House. ISBN 0-940859-09-2.

External links

[edit]Chicago Loop

View on GrokipediaHistory

Etymology and naming origins

The designation "the Loop" derives from the rectangular circuit of elevated railroad tracks constructed by the Union Elevated Railroad Company, which enclosed Chicago's central business district following its incorporation in November 1894 and completion on October 3, 1897.[8] This 1.79-mile steel structure, designed by bridge engineer John Alexander Low Waddell, connected four pre-existing elevated lines at Lake Street (north), Wabash Avenue (east), Van Buren Street (south), and Wells Street (west), forming a shared terminal loop that facilitated efficient transit access to the enclosed commercial core.[9][10] The engineering rationale prioritized a closed-loop configuration to alleviate congestion from radial rail approaches, distinguishing the area physically from the wider "Central Business District" moniker used in earlier city planning documents and rail records, which lacked reference to such bounding infrastructure.[11] Contemporary accounts in rail company proceedings and local reporting tied the name directly to this track geometry, rather than prior cable car routes or informal usage, as the elevated loop's completion marked the first engineered enclosure of the district, prompting residents and operators to adopt "the Loop" for the demarcated zone.[10] Chicago Surface Lines records and early 20th-century transit maps further reinforced this association, depicting the elevated rectangle as the defining perimeter, with no equivalent looped cable infrastructure achieving similar prominence or permanence prior to 1897.[12]19th-century foundations and early infrastructure

The area that would become known as the Chicago Loop began solidifying as the city's commercial nucleus in the 1830s, fueled by anticipation of major transportation links that drew land speculators and early merchants to the swampy lakefront terrain south of the Chicago River.[13] The Illinois and Michigan Canal's completion on April 10, 1848—after delays from the Panic of 1837—linked Lake Michigan directly to the Illinois River and thus the Mississippi system, enabling efficient shipment of lumber, grain, and other goods; this 96-mile waterway immediately boosted Chicago's population from about 20,000 to over 30,000 within two years and established the central riverfront as a warehousing and trading epicenter.[14][15] Railroad development accelerated this transformation, with the first lines arriving in 1848 and converging on the Loop district by the 1850s, creating a nexus for freight transfer that handled millions of bushels of grain annually by the 1860s.[16] By 1856, ten rail companies operated terminals in the area, prioritizing commercial infrastructure like depots and sidings over housing, which shifted residential settlement outward; deed records from the era reflect this, with core parcels leased predominantly for mercantile uses rather than homes, as proximity to transfer points maximized economic rents from trade volumes exceeding those of any other U.S. city.[17] This pattern stemmed from causal incentives of low transport costs and high throughput, drawing an influx of about 100,000 settlers by 1860, mostly laborers and traders supporting the booms. The Great Chicago Fire, ignited on October 8, 1871, razed 3.3 square miles of the densest commercial zone, incinerating 17,450 structures, killing around 300 people, and inflicting $200 million in damages—equivalent to one-third of the city's assessed value.[18] Reconstruction, completed for over 80% of the core by late 1872, incorporated fire-resistant mandates from 1872 ordinances requiring brick exteriors, stone foundations, and iron interiors for new builds taller than two stories, averting total collapse in subsequent blazes like the 1874 fire.[19] These measures enabled precursors to skyscrapers, such as multi-story masonry blocks reaching six to ten floors with internal iron framing for load-bearing efficiency, tested in structures like the 1873 Newhall Building; empirical data from insurance assessments post-rebuild show a 40% reduction in fire losses per capita compared to pre-1871 levels, reinforcing the district's viability for intensive business clustering.[18][20]Late 19th to early 20th-century expansion and the Elevated Loop

The Union Elevated Railroad's loop tracks, encircling the central business district, were substantially completed by 1897 following construction that began in 1895, providing a critical infrastructure for alleviating street-level congestion caused by horse-drawn vehicles and cable cars.[8] This elevated system enabled more efficient commuter access, fostering denser commercial development by separating rail traffic from ground-level commerce and reducing bottlenecks that previously limited land use intensity in the Loop.[21] Early ridership on Chicago's elevated lines grew rapidly, reaching approximately 505.9 million passenger journeys by 1906, reflecting the system's role in supporting urban expansion amid rising population and economic activity.[22] Parallel to this transit advancement, the Loop experienced a skyscraper boom driven by structural innovations in steel framing, which allowed buildings to exceed traditional masonry height constraints imposed by load-bearing walls and post-1871 fire safety regulations mandating non-combustible materials like brick and iron.[23] The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885 and designed by William Le Baron Jenney, pioneered this approach with its iron-and-steel skeleton supporting 10 stories (later expanded to 12), marking the first instance of a tall structure relying primarily on a metal frame rather than thick perimeter walls, thus enabling vertical growth to maximize scarce downtown land amid high property values.[23] Fire codes from the era, while enforcing fire-resistant construction within designated limits, did not initially cap heights strictly but emphasized material durability, with later ordinances like the 1902 restriction to 130 feet reflecting ongoing tensions between innovation and safety concerns.[24][25] The 1893 World's Columbian Exposition further catalyzed investment in the Loop by drawing over 20 million visitors to Chicago, stimulating retail and commercial sectors through heightened tourism and infrastructure spending despite coinciding with the Panic of 1893 financial crisis.[26] This influx promoted urban beautification and architectural experimentation, indirectly boosting Loop property values and office demand as the fair showcased Chicago's capabilities, leading to sustained economic spillover in core districts even as the event itself occurred southward in Jackson Park.[27] The combination of elevated rail efficiency and skeletal construction thus causally linked technological advancements to the district's densification, prioritizing functional capacity over aesthetic precedents in shaping early high-rise proliferation.[28]Mid-20th-century transformations and urban renewal

In the 1950s, construction of the Eisenhower Expressway (I-290), completed between 1949 and 1961 at a cost of $183 million, profoundly altered the western approaches to the Chicago Loop by demolishing over 13,000 residences and 400 businesses in the adjacent Near West Side neighborhoods, primarily inhabited by Italian, Greek, and Eastern European immigrant communities.[29][30] This federally funded project, part of the broader Interstate Highway System initiated by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, aimed to alleviate congestion and enhance commuter access to the Loop's central business district, ultimately reducing travel times from suburbs and improving goods movement into the city core.[31] However, the sunken roadway and elevated sections created physical barriers that fragmented communities, scattered ethnic enclaves, and exacerbated social isolation without commensurate reinvestment in displaced populations, contributing to long-term economic disinvestment in bordering areas.[29] Amid postwar deindustrialization, the Loop experienced a surge in white-collar office employment as manufacturing jobs migrated outward, with the central business district maintaining roughly stable workforce levels around 500,000 by the late 1950s while absorbing shifts from heavy industry to finance, insurance, and professional services.[32] This transition reflected broader national trends where urban cores like the Loop prioritized high-rise office expansions to attract corporate headquarters and clerical workers, yet it coincided with suburbanization pressures that strained infrastructure and prompted aggressive highway builds to sustain Loop vitality.[33] Government-led initiatives, including expressway extensions like the Kennedy (I-90/94, opened 1960), funneled commuters but induced reliance on automobiles, undermining the Loop's historic pedestrian and rail-oriented economy without addressing underlying fiscal inefficiencies in public planning.[34] Urban renewal programs under the Housing Act of 1949, applied to Loop-adjacent zones, targeted "blight" through slum clearance but often resulted in inefficiencies, displacing tens of thousands citywide—estimated at 81,000 by the late 1970s from combined freeway and renewal efforts—while leaving cleared sites underutilized due to mismatched public subsidies and private hesitancy.[35] In surrounding districts, such top-down demolitions failed to generate equivalent replacement housing or jobs, fostering persistent vacancy and decay as relocated residents strained peripheral resources, contrasting with organic private investments that had previously sustained mixed-use vitality.[36] Critics, including affected community leaders, highlighted how these policies prioritized infrastructure over human capital, accelerating white-collar suburban migration and entrenching economic divides without empirical validation of long-term benefits, as evidenced by stalled redevelopment in cleared West Side parcels.[29]Late 20th to early 21st-century developments

In the 1970s, Chicago initiated efforts to counter retail decline in the Loop by pedestrianizing a nine-block section of State Street in 1979, barring private vehicles to emulate suburban malls and prioritize shoppers, buses, taxis, and deliveries. This $12 million project expanded sidewalks and added amenities but faltered amid falling sales, as restricted access deterred customers and failed to stem suburban competition. By 1996, amid persistent vacancies, the city reversed course, restoring two-way vehicular traffic and narrowing sidewalks, which catalyzed a revival with new anchors like Old Navy opening stores and drawing increased foot traffic. This shift aligned with broader 1990s tourism growth, where visitor numbers surged, spurring hotel expansions and restaurant booms that amplified Loop retail revenues despite earlier regulatory missteps in urban planning.[37][38][39][40] Millennium Park's development from 1997 to 2004 exemplified a public-private model to modernize underused Grant Park rail yards into a 24.5-acre venue featuring the Cloud Gate sculpture and Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Total costs reached $490 million, with public funds covering $270 million for infrastructure and private contributions—via donations and sponsorships—supplying $220 million, enabling features beyond initial budgets despite delays from permitting and litigation. Opened in 2004, the park drew 3 million visitors in 2005, escalating to 5 million by 2010, yielding returns through $1.4 billion in spurred residential development and elevated property tax bases, as private investment mitigated fiscal limits and bureaucratic obstacles.[41][42][43][44][45] The Loop's late 1990s and 2000s saw finance firms consolidate amid the tech shift, with market advantages like proximity to exchanges drawing operations despite zoning constraints slowing builds. Chicago hosted relocations such as Boeing's 2001 headquarters move, bolstering white-collar jobs near the core, while entities like Kemper Corporation and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange anchored finance in high-rises. This influx, fueled by the 1990s tech boom nationalizing industries toward central hubs, grew corporate presence without heavy reliance on subsidies, as firms prioritized talent pools and logistics over incentives.[46][47][48]Recent 21st-century changes including post-COVID recovery and 2025 initiatives

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the Chicago Loop's office-centric economy, with office vacancy rates surging from approximately 11% in early 2020 to over 20% by mid-2021 amid widespread remote work adoption and business retrenchment.[49] Foot traffic plummeted by up to 80% in 2020 compared to 2019 baselines, exacerbating retail and transit declines as lockdowns and hybrid work policies reduced daily commuter volumes.[50] By 2022, persistent remote work—facilitated by firms retaining leased space without full occupancy—locked in elevated vacancies around 25%, challenging causal assumptions that temporary disruptions would swiftly reverse without policy interventions addressing underlying incentives like tax burdens.[51] Recovery efforts from 2023 onward showed mixed empirical progress, with office vacancy stabilizing but climbing to a record 28% in the central business district by Q3 2025, driven by sublease additions and subdued leasing amid ongoing hybrid models.[51] Pedestrian counts rebounded unevenly, surpassing 2019 levels in Q3 2025 due to targeted arts, culture, and event programming, with weekend traffic up to 55% higher than pre-pandemic figures in key corridors like State Street.[52][53] However, weekday office visits lagged, rising only 12.5% year-over-year in mid-2025 while remaining below 2019 peaks, underscoring remote work's enduring causal impact on core district vitality rather than transient pandemic effects.[54] In 2025, the city unveiled the Central Area Plan 2045, a framework promoting office-to-residential conversions to repurpose vacant space and target 300,000 downtown residents by mid-century—more than doubling the Loop's current population—through mixed-use developments and streamlined incentives for moderate-income housing.[55][56] Complementary initiatives included the LaSalle Street public realm improvements, launched in January 2025, aiming to enhance pedestrian connectivity between Wacker Drive and Jackson Boulevard via community-led redesigns.[57] The Chicago Loop Alliance expanded event programming to sustain foot traffic gains, though these measures face headwinds from Illinois' accelerated business outflows—218 firms relocated out-of-state in 2023 alone, tripling pre-pandemic rates—attributed to high property and income taxes eroding investment appeal and questioning the plans' long-term sustainability absent fiscal reforms.[58][59]Geography and Demographics

Defined boundaries and physical layout

The Chicago Loop district is delineated by the Chicago River along its northern and western edges, Ida B. Wells Drive (formerly Congress Parkway) to the south, and Lake Michigan to the east, encompassing the central business core of downtown Chicago.[2] This configuration aligns with municipal community area mappings, covering approximately 1.66 square miles.[60] The designation "Loop" specifically derives from the enclosed rectangular path of the Chicago Transit Authority's elevated 'L' rail tracks, which circumscribe the historic core bounded roughly by Lake Street to the north, Wacker Drive to the west (paralleling the river), Van Buren Street to the south, and Wabash Avenue to the east, forming a compact 35-block area central to commercial activity.[61] The physical layout occupies flat glacial plain terrain, characteristic of the former lakebed of ancestral Lake Chicago, with average elevations around 600 feet above sea level—marginally higher than Lake Michigan's surface due to 19th-century engineering efforts to elevate streets above flood-prone levels.[62] [63] The Chicago River's branching confluence at Wolf Point historically dictated the irregular western boundary, integrating waterways into the urban grid while facilitating early industrial and transport development.[64] The area exhibits high urban density, dominated by high-rise structures exceeding 20 stories on average, contributing to a vertical skyline profile.[65]Key neighborhoods and districts

The Chicago Loop features several specialized districts shaped by historical land uses and evolving economic functions, with zoning patterns reflecting concentrations of finance, retail, and mixed-use development. The northeastern quadrant, encompassing areas around LaSalle Street and the Chicago Board of Trade, functions primarily as a finance and trading hub, where high-density office zoning supports commodity exchanges and banking operations established since the 19th century. The core retail corridor along State Street and adjacent blocks operates under commercial zoning that prioritizes shopping and entertainment, hosting historic department stores and theaters that draw pedestrian traffic for consumer-oriented activities.[66] The Historic Michigan Boulevard District, a designated landmark along Michigan Avenue from Roosevelt Road to Randolph Street, maintains a commercial streetwall of early skyscrapers zoned for office and retail, preserving a cohesive facade that underscores the area's role in corporate headquarters and professional services.[67] In the eastern sector, the New Eastside—encompassing Lakeshore East—has transitioned via mixed-use zoning to emphasize residential high-rises amid office and park spaces, with developments on former rail yards adding over 5,000 condominium units since 2000 to support downtown living proximate to financial centers.[68] Printer's Row, at the district's southern periphery near Dearborn and Polk streets, originated as a printing industry cluster in the 1880s under industrial zoning that facilitated bookbinding and publishing operations, though buildings have since adapted to loft-style commercial and event uses following the sector's decline post-1950s.[69]Population trends and demographic composition

The Chicago Loop's resident population has grown steadily since 2010, reflecting conversions of commercial space to housing amid broader downtown revitalization efforts, yet it remains dwarfed by daytime influxes from commuters, underscoring the area's persistent orientation as a business hub rather than a residential core. The 2010 Census recorded approximately 29,270 residents, increasing to 42,298 by 2020—a 44.5% rise, the fastest among Chicago's community areas—driven by high-rise apartment and condominium developments.[70] By 2022, estimates placed the nighttime population at 46,000, continuing modest expansion even during the COVID-19 pandemic as remote work trends temporarily reduced commuting but did not halt inbound migration to urban amenities.[71] Projections for 2025 suggest stabilization around 48,000–50,000 residents, tempered by citywide factors such as elevated living costs and perceptions of crime, though Loop-specific data indicate lower violent and property crime shares relative to Chicago overall (less than 1% of citywide violent crime increases from 2019–2022).[72] This growth trajectory challenges assumptions of a seamless live-work equilibrium, as resident numbers constitute only a fraction of peak daily occupancy, with historical daytime populations exceeding 500,000 pre-pandemic due to an estimated 300,000–400,000 jobs in finance, law, and professional services drawing workers from suburbs and exurbs.[73]| Year | Resident Population Estimate |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 29,270 |

| 2020 | 42,298 |

| 2022 | 46,000 |