Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

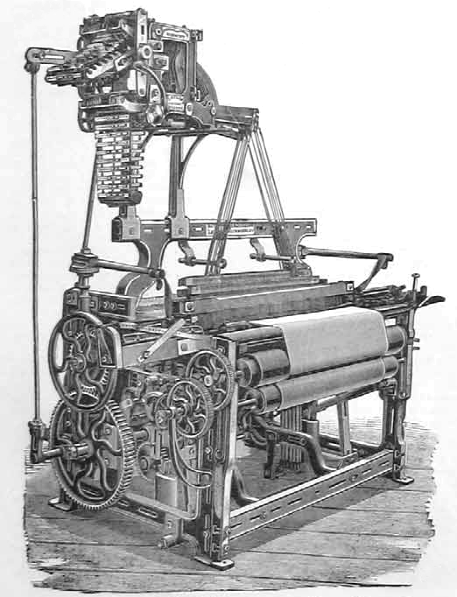

Dobby loom

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

A dobby loom, or dobbie loom,[1] is a type of floor loom that controls all the warp threads using a device called a dobby.[2]

Dobbies can produce more complex fabric designs than tappet looms[2] but are limited in comparison to Jacquard looms. Dobby looms first appeared around 1843, roughly 40 years after Joseph Marie Jacquard invented the Jacquard device that can be mounted atop a loom to lift the individual heddles and warp threads.

The word dobby is a corruption of "draw boy," which refers to the weaver's helpers who used to control the warp thread by pulling on draw threads. A dobby loom is an alternative to a treadle loom. Both are floor looms in which every warp thread on the loom is attached to a single shaft using a device called a heddle. A shaft is sometimes known as a harness. Each shaft controls a set of threads. Raising or lowering several shafts at the same time gives a huge variety of possible sheds (gaps) through which the shuttle containing the weft thread can be thrown.

Control

[edit]

A manual dobby uses a chain of bars or lags each of which has pegs inserted to select the shafts to be moved. A computer-assisted dobby loom uses a set of solenoids or other electric devices to select the shafts. Activation of these solenoids is under the control of a computer program. In either case the selected shafts are raised or lowered by either leg power on a dobby pedal or electric or other power sources.

Manual

[edit]On a treadle loom, each foot-operated treadle is connected by a linkage called a tie-up to one or more shafts. More than one treadle can operate a single shaft. The tie-up consists of cords or similar mechanical linkages tying the treadles to the lams that actually lift or lower the shaft.

On treadle operated looms, the number of sheds is limited by the number of treadles available. An eight-shaft loom can create 254 different sheds. There are actually 256 possibilities, which is 2 to the eighth power, but having all threads up or all threads down is not very useful. Most eight-shaft floor looms have only ten to twelve treadles due to space limitations. This limits the weaver to ten to twelve distinct sheds. It is possible to use both feet to get more sheds, but this is rarely done in practice. It is even possible to change tie-ups in the middle of weaving a cloth but this is a tedious process, so this too is rarely done.

With a dobby loom, all 254 possibilities are available at any time. This vastly increases the number of cloth designs available to the weaver. The advantage of a dobby loom becomes even more pronounced on looms with 12 shafts (4094 possible sheds), 16 shafts (65,534 possible sheds), or more. It reaches its peak on a Jacquard loom in which each thread is individually controlled.

Another advantage to a dobby loom is the ability to handle much longer sequences in the pattern. A weaver working on a treadle loom must remember the entire sequence of treadlings that make up the pattern, and must keep track of where they are in the sequence at all times. Getting lost or making a mistake can ruin the cloth being woven. On a manual dobby the sequence that makes up the pattern is represented by the chain of dobby bars. The length of the sequence is limited by the length of the dobby chain. This can easily be several hundred dobby bars, although an average dobby chain will have approximately fifty bars.

Computer

[edit]A computer-controlled dobby loom takes this one step further by replacing the mechanical dobby chain with computer-controlled shaft selection. In addition to being able to handle sequences that are virtually unlimited, the construction of the shaft sequences is done on the computer screen rather than by building a mechanical dobby chain. This allows the weaver to load and switch weave drafts in seconds without even getting up from the loom. In addition, the design process performed on the computer provides the weaver with a more intuitive way to design fabric; seeing the pattern on a computer screen is easier than trying to visualize it by looking at the dobby chain.

Dobby looms expand a weaver's capabilities and remove some of the tedious work involved in designing and producing fabric. Many newer cloth design techniques such as network drafting can only reach their full potential on a dobby loom.

See also

[edit]- Dobby (cloth) - the cloth made on a dobby loom.

References

[edit]- ^ Piece Goods Manual at Project Gutenberg

- ^ a b Roberts, Thomas (1920). Tappet and Dobby Looms Their Mechanism and Management. Manchester: Emmett and Co.