Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multiple buffering

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In computer science, multiple buffering is the use of more than one buffer to hold a block of data, so that a "reader" will see a complete (though perhaps old) version of the data instead of a partially updated version of the data being created by a "writer". It is very commonly used for computer display images. It is also used to avoid the need to use dual-ported RAM (DPRAM) when the readers and writers are different devices.

Description

[edit]Double buffering Petri net

[edit]The Petri net in the illustration shows double buffering. Transitions W1 and W2 represent writing to buffer 1 and 2 respectively while R1 and R2 represent reading from buffer 1 and 2 respectively. At the beginning, only the transition W1 is enabled. After W1 fires, R1 and W2 are both enabled and can proceed in parallel. When they finish, R2 and W1 proceed in parallel and so on.

After the initial transient where W1 fires alone, this system is periodic and the transitions are enabled – always in pairs (R1 with W2 and R2 with W1 respectively).

Double buffering in computer graphics

[edit]In computer graphics, double buffering is a technique for drawing graphics that shows less stutter, tearing, and other artifacts.

It is difficult for a program to draw a display so that pixels do not change more than once. For instance, when updating a page of text, it is much easier to clear the entire page and then draw the letters than to somehow erase only the pixels that are used in old letters but not in new ones. However, this intermediate image is seen by the user as flickering. In addition, computer monitors constantly redraw the visible video page (traditionally at around 60 times a second), so even a perfect update may be visible momentarily as a horizontal divider between the "new" image and the un-redrawn "old" image, known as tearing.

Software double buffering

[edit]A software implementation of double buffering has all drawing operations store their results in some region of system RAM; any such region is often called a "back buffer". When all drawing operations are considered complete, the whole region (or only the changed portion) is copied into the video RAM (the "front buffer"); this copying is usually synchronized with the monitor's raster beam in order to avoid tearing. Software implementations of double buffering necessarily require more memory and CPU time than single buffering because of the system memory allocated for the back buffer, the time for the copy operation, and the time waiting for synchronization.

Compositing window managers often combine the "copying" operation with "compositing" used to position windows, transform them with scale or warping effects, and make portions transparent. Thus, the "front buffer" may contain only the composite image seen on the screen, while there is a different "back buffer" for every window containing the non-composited image of the entire window contents.

Page flipping

[edit]In the page-flip method, instead of copying the data, both buffers are capable of being displayed. At any one time, one buffer is actively being displayed by the monitor, while the other, background buffer is being drawn. When the background buffer is complete, the roles of the two are switched. The page-flip is typically accomplished by modifying a hardware register in the video display controller—the value of a pointer to the beginning of the display data in the video memory.

The page-flip is much faster than copying the data and can guarantee that tearing will not be seen as long as the pages are switched over during the monitor's vertical blanking interval—the blank period when no video data is being drawn. The currently active and visible buffer is called the front buffer, while the background page is called the back buffer.

Triple buffering

[edit]In computer graphics, triple buffering is similar to double buffering but can provide improved performance. In double buffering, the program must wait until the finished drawing is copied or swapped before starting the next drawing. This waiting period could be several milliseconds during which neither buffer can be touched.

In triple buffering, the program has two back buffers and can immediately start drawing in the one that is not involved in such copying. The third buffer, the front buffer, is read by the graphics card to display the image on the monitor. Once the image has been sent to the monitor, the front buffer is flipped with (or copied from) the back buffer holding the most recent complete image. Since one of the back buffers is always complete, the graphics card never has to wait for the software to complete. Consequently, the software and the graphics card are completely independent and can run at their own pace. Finally, the displayed image was started without waiting for synchronization and thus with minimum lag.[1]

Due to the software algorithm not polling the graphics hardware for monitor refresh events, the algorithm may continuously draw additional frames as fast as the hardware can render them. For frames that are completed much faster than interval between refreshes, it is possible to replace a back buffers' frames with newer iterations multiple times before copying. This means frames may be written to the back buffer that are never used at all before being overwritten by successive frames. Nvidia has implemented this method under the name "Fast Sync".[2]

An alternative method sometimes referred to as triple buffering is a swap chain three buffers long. After the program has drawn both back buffers, it waits until the first one is placed on the screen, before drawing another back buffer (i.e. it is a 3-long first in, first out queue). Most Windows games seem to refer to this method when enabling triple buffering.[citation needed]

Quad buffering

[edit]The term quad buffering is the use of double buffering for each of the left and right eye images in stereoscopic implementations, thus four buffers total (if triple buffering was used then there would be six buffers). The command to swap or copy the buffer typically applies to both pairs at once, so at no time does one eye see an older image than the other eye.

Quad buffering requires special support in the graphics card drivers which is disabled for most consumer cards. AMD's Radeon HD 6000 Series and newer support it.[3]

3D standards like OpenGL[4] and Direct3D support quad buffering.

Double buffering for DMA

[edit]The term double buffering is used for copying data between two buffers for direct memory access (DMA) transfers, not for enhancing performance, but to meet specific addressing requirements of a device (particularly 32-bit devices on systems with wider addressing provided via Physical Address Extension).[5] Windows device drivers are a place where the term "double buffering" is likely to be used. Linux and BSD source code calls these "bounce buffers".[6]

Some programmers try to avoid this kind of double buffering with zero-copy techniques.

Other uses

[edit]Double buffering is also used as a technique to facilitate interlacing or deinterlacing of video signals.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Triple Buffering: Why We Love It". AnandTech. June 26, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Smith, Ryan. "The NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 & GTX 1070 Founders Editions Review: Kicking Off the FinFET Generation". Archived from the original on July 23, 2016. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ^ AMD Community

- ^ "OpenGL 3.0 Specification, Chapter 4" (PDF).

- ^ "Physical Address Extension - PAE Memory and Windows". Microsoft Windows Hardware Development Central. 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ Gorman, Mel. "Understanding The Linux Virtual Memory Manager, 10.4 Bounce Buffers".

External links

[edit]- Triple buffering: improve your PC gaming performance for free by Mike Doolittle (2007-05-24)

- Graphics 10 Archived 2016-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

Multiple buffering

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

Multiple buffering is a technique in computer science that employs more than one buffer to temporarily store blocks of data, enabling a reader process or component to access a complete, albeit potentially outdated, version of the data while a writer concurrently updates a separate buffer. This approach involves associating two or more input/output areas with a file or device, where data is pre-read or post-written under operating system control to facilitate seamless transitions between buffers.[4] In contrast, single buffering relies on a solitary buffer, which requires the consuming process to block and wait for the input/output operation to fully complete before proceeding with computation or display, leading to inefficiencies such as idle CPU time and potential data inconsistencies during access. This blocking nature limits overlap between data transfer and processing, particularly in scenarios involving slow peripheral devices or real-time requirements, where interruptions can degrade performance.[5] The primary purpose of multiple buffering is to mitigate these limitations by allowing parallel read and write operations, thereby reducing latency and preventing issues like data corruption or visual artifacts such as screen tearing in display systems.[4] It optimizes resource utilization in real-time environments by overlapping computation with input/output activities, minimizing waiting periods and supporting concurrent processing to enhance overall system throughput.[6] General benefits include improved efficiency in handling asynchronous data flows, which is essential across domains like graphics rendering and I/O-intensive applications, without necessitating specialized hardware like dual-ported RAM.Historical Development

The concept of buffering originated in the early days of computing during the 1960s, when mainframe systems required mechanisms to manage interactions between fast central processing units and slow peripherals such as magnetic tapes and drums. Buffers acted as temporary storage to cushion these mismatches, preventing CPU idle time during I/O operations.[7] A seminal contribution came from Jack B. Dennis and Earl C. Van Horn's 1966 paper, "Programming Semantics for Multiprogrammed Computations," which proposed segmented memory structures to enable efficient resource sharing and overlapping of computation and I/O in multiprogrammed environments, laying foundational ideas for multiple buffering techniques.[8] By the 1970s, these ideas influenced batch processing systems, where double buffering emerged to allow one buffer to be filled with input data while another was processed, reducing delays and improving throughput in operating systems handling sequential jobs.[9] A key milestone in graphics applications occurred in 1973 with the Xerox Alto computer at PARC, which featured a dedicated frame buffer using DRAM to store and refresh bitmap display data.[10] This approach pioneered buffering for interactive visuals in personal computing. In the 1980s, buffering techniques were formalized in operating system literature, notably in UNIX, where buffer caches were implemented to optimize file system I/O by caching disk blocks in memory, with significant enhancements around 1980 to support larger buffer pools and reduce physical I/O calls.[11] Concurrently, Digital Equipment Corporation's VMS (released in 1977 and evolving into OpenVMS) adopted advanced buffering in its Record Management Services (RMS), using local and global buffer caches to share I/O resources across processes efficiently.[12] The 1990s marked an evolution toward multiple buffering beyond double setups, driven by the rise of 3D graphics acceleration. Silicon Graphics Incorporated (SGI) workstations, running IRIX, integrated support for triple buffering to minimize tearing and latency in real-time rendering. This was formalized in APIs such as OpenGL 1.0 (1992), developed by SGI, which provided core support for double buffering via swap buffers and extensions for additional back buffers to handle complex 3D scenes.[13] Microsoft's DirectX, introduced in 1995, extended these concepts to Windows platforms, incorporating multiple buffering in Direct3D for smoother graphics on consumer hardware. Early Windows NT versions (from 1993) further adopted robust buffering inspired by VMS designs, with kernel-level I/O managers using multiple buffers to enhance reliability in multitasking environments.Basic Principles

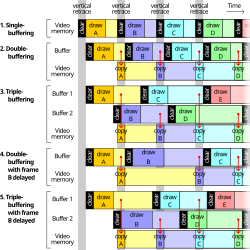

Multiple buffering operates on the principle of employing more than one buffer to manage data flow between producers and consumers, enabling concurrent read and write operations without interference. In the core mechanism, typically two buffers are designated: a front buffer, which holds the current data being read or displayed by the consumer, and a back buffer, into which the producer writes new data. Upon completion of writing to the back buffer, the buffers are swapped atomically, making the updated content available to the consumer instantaneously while the former front buffer becomes the new back buffer for the next write cycle. This alternation ensures that the consumer always accesses complete, consistent data, preventing partial updates or artifacts during the transition.[14] A formal representation of this process can be modeled using a Petri net, which captures the state transitions and resource allocation in double buffering. In this model, places represent the buffers and their states, such as Buffer 0 in an acquiring state (holding raw data) or a ready-to-acquire state, and Buffer 1 in a processing or transmission state. Transitions correspond to key operations: writing or acquiring data (e.g., firing from acquiring to processing via a buffer swap), reading or processing (e.g., executing computations on the active buffer), and swapping buffers to alternate roles. Tokens in the net symbolize data presence or availability, with one token typically indicating a buffer containing valid data ready for the next operation. The system begins in an initial transient phase, where the first buffer acquires data without overlap, establishing the initial token placement. This evolves into a periodic steady state, where the net cycles through alternating buffer usages—such as state sequences from acquisition to processing, swap, and back—ensuring continuous, non-blocking operation without deadlocks.[15] Synchronization is critical to prevent race conditions during buffer swaps, particularly in time-sensitive applications like rendering. Signals such as the vertical blanking interval (VBI)—the brief period when a display device is not actively drawing pixels—serve this purpose by providing a safe window for swapping buffers. During VBI, which occurs approximately 60 times per second in standard displays, the swap is timed to coincide with the retrace, ensuring the consumer sees only fully rendered frames and avoiding visible tearing or inconsistencies. This mechanism enforces vertical synchronization, aligning buffer updates with the display's refresh cycle to maintain smooth data presentation.[16] The double buffering model generalizes to n-buffers, where additional buffers (n > 2) allow for greater overlap between production, consumption, and transfer operations, further reducing idle wait times. In this extension, multiple buffer sets enable pipelining: while one buffer is consumed, others can be filled or processed in parallel, minimizing downtime provided the kernel execution time and transfer latencies satisfy overlap conditions (e.g., transfer and operation times fitting within (n-1) cycles). However, this comes at the cost of increased memory usage, as n full buffer sets must be allocated on both producer and consumer sides, scaling linearly with n.[17]Buffering in Computer Graphics

Double Buffering Techniques

In computer graphics, double buffering employs two distinct frame buffers: a front buffer, which holds the currently displayed image, and a back buffer, to which new frames are rendered off-screen. This separation allows the rendering process to occur without interfering with the display scan-out, thereby preventing visual artifacts such as screen tearing—where parts of two different frames appear simultaneously due to mismatched rendering and display timings—and flicker from incremental updates. Upon completion of rendering to the back buffer, the buffers are swapped, making the newly rendered content visible while the previous front buffer becomes the new back buffer for the next frame.[18][19] Software double buffering involves rendering graphics primitives to an off-screen memory buffer in system RAM, followed by a bitwise copy (blit) operation to transfer the completed frame to the video RAM for display. To minimize partial updates and tearing, this copy is typically synchronized with the vertical blanking interval (VBI), the period when the display hardware is not scanning pixels, ensuring atomic swaps. This approach, common in early graphics systems and software libraries like Swing in Java, reduces CPU overhead compared to direct screen writes but incurs performance costs from the memory transfer, particularly on systems with limited bandwidth.[18][16] Page flipping represents a hardware-accelerated variant of double buffering, where both buffers reside in video memory, and swapping occurs by updating GPU registers to redirect the display controller's pointer from the front buffer to the back buffer, without copying pixel data. This technique, supported in modern GPUs through mechanisms like Direct3D swap chains or OpenGL contexts, achieves near-instantaneous swaps during VBI, significantly reducing CPU involvement and memory bandwidth usage compared to software methods—often by orders of magnitude in transfer time. For instance, in full-screen exclusive modes, page flipping enables efficient animation by leveraging hardware capabilities to alternate between buffers seamlessly.[18][19] Despite these benefits, double buffering techniques face challenges including dependency on vertical synchronization (VSync) to align swaps with display refresh rates, which can introduce latency if rendering exceeds frame intervals, and constraints from memory bandwidth in software implementations or GPU register access in page flipping. In contemporary APIs, such as OpenGL'sglSwapBuffers() function, which initiates the buffer exchange and often implies page flipping on compatible hardware, developers must manage these issues to balance smoothness and responsiveness, particularly in variable-rate rendering scenarios.[20][16]

Triple Buffering

Triple buffering extends the double buffering technique by employing three frame buffers: one front buffer for display and two back buffers for rendering. In this setup, the graphics processing unit (GPU) renders the next frame into the unused back buffer while the display controller reads from the front buffer and the other back buffer awaits swapping. This allows the GPU to continue rendering without stalling for vertical synchronization (vsync) intervals, decoupling the rendering rate from the display refresh rate.[21][22] The primary benefits of triple buffering include achieving higher frame rates in GPU-bound scenarios compared to double buffering with vsync enabled, as the GPU avoids idle time during buffer swaps. It also reduces visual stutter and eliminates screen tearing by ensuring a ready frame is always available for presentation, enhancing smoothness in real-time graphics applications like games. In modern graphics APIs, this is facilitated through swap chains, where a buffer count of three enables the queuing of rendered frames for deferred presentation. For instance, in DirectX 11 and 12, swap chains support multiple back buffers to implement this behavior, while Vulkan uses image counts greater than two in swapchains for similar effects.[22][23][24] Despite these advantages, triple buffering requires 1.5 times the memory of double buffering due to the additional back buffer, which can strain systems with limited video RAM. Additionally, it may introduce up to one frame of increased input latency, as frames are queued ahead, potentially delaying user interactions in latency-sensitive applications. Poor management can also lead to the presentation of outdated frames if the rendering pipeline overruns. Implementation often involves driver-level options, such as the triple buffering toggle in the NVIDIA Control Panel, available since the early 2000s for OpenGL and DirectX applications, allowing developers and users to enable it per game or globally.[25][26][27]Quad Buffering

Quad buffering, also known as quad-buffered stereo, is a rendering technique in computer graphics designed specifically for stereoscopic 3D applications. It utilizes four separate buffers: a front buffer and a back buffer for the left-eye view, and corresponding front and back buffers for the right-eye view. This configuration effectively provides double buffering for each eye independently, allowing the graphics pipeline to render and swap left and right frames alternately, typically synchronized to the display's vertical refresh rate to alternate views per frame.[28][29] The core purpose of quad buffering is to enable tear-free, high-fidelity stereoscopic rendering in real-time 3D environments, where separate eye views must be presented sequentially without visual artifacts. By isolating the buffering process for each eye, it supports frame-sequential stereo output to hardware like active shutter glasses, 120 Hz LCD panels, or specialized projection systems, ensuring smooth depth perception in immersive scenes. This approach requires explicit hardware and driver support, achieved in OpenGL by requesting a stereo-enabled context through extensions such as WGL_STEREO_EXT for Windows (via WGL) or GLX_STEREO for Linux/X11 (via GLX), which configures the framebuffer to allocate the additional buffers. Quad buffering has been supported in professional graphics hardware since the early 1990s, such as in Silicon Graphics (SGI) workstations with OpenGL.[30][29][31][32] Quad buffering gained broader implementation in the 2010s, notably with the AMD Radeon HD 6000 series GPUs, which integrated quad buffer support through AMD's HD3D technology and the accompanying Quad Buffer SDK. This enabled native stereo rendering in OpenGL and DirectX applications for professional visualization, such as molecular modeling in tools like VMD or CAD workflows, as well as precursors to VR/AR systems requiring precise binocular disparity. NVIDIA's Quadro series similarly provided dedicated quad buffer modes for these domains, often paired with stereo emitters to drive synchronized displays.[33][29] Key limitations of quad buffering include its substantial video memory requirements, which are roughly double those of monoscopic double buffering since full framebuffers are duplicated per eye, potentially straining resources in high-resolution scenarios. Compatibility is further restricted to professional-grade GPUs with specialized drivers and circuitry for stereo synchronization, excluding most consumer hardware and leading to setup complexities in mixed environments. As a result, its adoption has waned with the rise of modern single-buffer stereo techniques that render both eyes in a unified pass, alongside VR headsets and alternative formats like side-by-side compositing, which offer greater efficiency and broader accessibility without dedicated quad buffer hardware.[29][30]Buffering in Data Processing

Double Buffering for DMA

Double buffering in the context of direct memory access (DMA) employs two separate buffers that alternate roles during data transfers between peripheral devices and system memory. While one buffer is actively involved in the DMA transfer—being filled by the device or emptied to it—the other buffer can be simultaneously processed by the CPU or software, enabling overlap between transfer and computation phases to maintain continuous operation without stalling the system. This mechanism is particularly valuable in scenarios where device speeds and memory access rates differ, allowing the overall pipeline to sustain higher effective throughput by hiding latency.[34] A primary use case for double buffering arises in ensuring compatibility for legacy or limited-capability hardware on modern systems. For instance, in Linux and BSD operating systems, bounce buffers implement this technique to handle DMA operations from 32-bit devices on 64-bit architectures, where the device cannot directly address high memory regions above 4 GB. The kernel allocates temporary low-memory buffers; data destined for high memory is first transferred via DMA to these bounce buffers, then copied by the CPU to the final destination, and vice versa for writes. Similarly, in the Windows driver model, double buffering is automatically applied for peripheral I/O when devices lack 64-bit addressing support, routing transfers through intermediate buffers to bridge the addressing gap.[34] The advantages of double buffering in DMA include reduced CPU intervention and the potential for zero-copy data handling in optimized configurations. By offloading transfers to the DMA controller and using interrupts to signal buffer swaps, the CPU avoids polling or direct involvement in each data movement, freeing it for other tasks. In setups employing coherent memory allocation, such as with DMA-mapped buffers shared between kernel and user space, this can eliminate unnecessary copies, achieving zero-copy efficiency. Examples include SCSI host adapters, where double buffering facilitates reliable block transfers without host processor bottlenecks, and network adapters, where it overlaps packet reception with protocol processing to sustain line-rate performance even under load. Technically, buffers for DMA double buffering are allocated in kernel space to ensure physical contiguity and proper alignment, often using APIs likedma_alloc_coherent() in Linux for cache-coherent mappings or equivalent bus_dma functions in BSD. Swaps between buffers are typically interrupt-driven: upon completion of a transfer to one buffer, a DMA interrupt handler updates the controller's descriptors to point to the alternate buffer and notifies the system to process the completed one. This interrupt-based coordination minimizes overhead compared to polling. In terms of performance, double buffering enables throughput that approximates the minimum of the device's transfer speed and the system's memory bandwidth, as the overlap prevents blocking delays that would otherwise limit the effective rate to the slower component.

Multiple Buffering in I/O Operations

Multiple buffering in input/output (I/O) operations refers to the use of more than two buffers to facilitate prefetching of data blocks or postwriting in file systems and data streams, enabling greater overlap between I/O activities and computational processing. This technique extends beyond basic double buffering by allocating a pool of buffers—typically ranging from 4 to 255 depending on the system—to anticipate sequential access patterns, thereby minimizing idle time for the CPU or application. In operating systems, multiple buffering is particularly effective for handling large sequential reads or writes, where data is loaded into unused buffers asynchronously while the current buffer is being processed.[35] One prominent implementation is found in IBM z/OS, where multiple buffering supports asynchronous I/O for data sets by pre-reading blocks into a specified number of buffers before they are required, thus eliminating delays from synchronous waits. The number of buffers is controlled via theBUFNO= parameter in the Data Control Block (DCB), allowing values from 2 to 255 for QSAM access methods, with defaults often set to higher counts for sequential processing to optimize throughput. Similarly, in UNIX-like systems such as Linux, the readahead mechanism employs multiple page-sized buffers (typically up to 32 pages, or 128 KB) in the page cache to prefetch sequential data blocks asynchronously, triggered by access patterns and scaled dynamically based on historical reads. This prefetching uses functions like page_cache_async_ra() to issue non-blocking I/O requests for anticipated pages, enhancing file system performance without explicit application intervention.[35][36][37]

The primary benefits of multiple buffering in I/O operations include significant reductions in latency for sequential access workloads, as prefetching amortizes the cost of disk seeks across multiple blocks and allows continuous data flow. For instance, in sequential file reads, it overlaps I/O completion with processing, while adaptive sizing—where buffer counts adjust based on workload detection, such as doubling readahead windows after consistent sequential hits—prevents over-allocation of memory in mixed access scenarios. These gains are workload-dependent, with the highest impact in streaming or batch processing where access predictability is high.[35][37][38]

Practical examples illustrate these concepts in specialized contexts. In database systems, transaction logs often utilize ring buffers—a circular form of multiple buffering with a fixed capacity, such as 256 entries in SQL Server's diagnostic ring buffers—to continuously capture log entries without unbounded memory growth, overwriting oldest data upon overflow to maintain low-latency writes during high-volume transactions. For modern storage, NVMe SSDs since their 2011 specification leverage up to 65,536 queues per device, each functioning as an independent buffer channel for parallel I/O submissions, enabling optimizations like asynchronous prefetch across multiple threads and reducing contention in multi-core environments for sequential workloads.[39][40][41]