Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

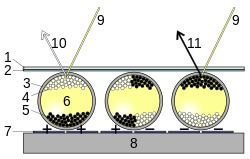

E Ink

View on Wikipedia

| Legend | Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | Upper layer |

| 2 | Transparent electrode layer |

| 3 | Transparent micro-capsules |

| 4 | Positively charged white pigments |

| 5 | Negatively charged black pigments |

| 6 | Transparent oil |

| 7 | Electrode pixel layer |

| 8 | Bottom supporting layer |

| 9 | Light |

| 10 | White |

| 11 | Black |

E Ink (electronic ink) is a brand of electronic paper (e-paper) display technology commercialized by the E Ink Corporation, which was co-founded in 1997 by MIT undergraduates JD Albert and Barrett Comiskey, MIT Media Lab professor Joseph Jacobson, Jerome Rubin and Russ Wilcox.[1]

It is available in grayscale and color[2] and is used in mobile devices such as e-readers, digital signage, smartwatches, mobile phones, electronic shelf labels and architecture panels.[3]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The notion of a low-power paper-like display had existed since the 1970s, originally conceived by researchers at Xerox PARC but had never been realized.[4] While a post-doctoral student at Stanford University, physicist Joseph Jacobson envisioned a multi-page book with content that could be changed at the push of a button and required little power to use.[5]

Neil Gershenfeld recruited Jacobson for the MIT Media Lab in 1995, after hearing Jacobson's ideas for an electronic book.[4] Jacobson, in turn, recruited MIT undergrads Barrett Comiskey, a math major, and J.D. Albert, a mechanical engineering major, to create the display technology required to realize his vision.[1]

Product development

[edit]The initial approach was to create tiny spheres which were half white and half black, and which, depending on the electric charge, would rotate such that the white side or the black side would be visible on the display. Albert and Comiskey were told this approach was impossible by most experienced chemists and materials scientists and had trouble creating these perfectly half-white, half-black spheres; during his experiments, Albert accidentally created some all-white spheres.[1]

Comiskey experimented with charging and encapsulating those all-white particles in microcapsules mixed in with a dark dye. The result was a system of microcapsules that could be applied to a surface and could then be charged independently to create black and white images.[1] A first patent was filed by MIT for the microencapsulated electrophoretic display in October 1996.[6]

The scientific paper was featured on the cover of Nature, something extremely unusual for work done by undergraduates. The advantage of the microencapsulated electrophoretic display and its potential for satisfying the practical requirements of electronic paper were summarized in the abstract of the Nature paper:

It has for many years been an ambition of researchers in display media to create a flexible low-cost system that is the electronic analogue of paper ... viewing characteristic[s] result in an "ink on paper" look. But such displays have to date suffered from short lifetimes and difficulty in manufacture. Here we report the synthesis of an electrophoretic ink based on the microencapsulation of an electrophoretic dispersion. The use of a microencapsulated electrophoretic medium solves the lifetime issues and permits the fabrication of a bistable electronic display solely by means of printing. This system may satisfy the practical requirements of electronic paper.[7]

A second patent was filed by MIT for the microencapsulated electrophoretic display in March 1997.[8]

Subsequently, Albert, Comiskey and Jacobson along with Russ Wilcox and Jerome Rubin founded the E Ink Corporation in 1997, two months prior to Albert and Comiskey's graduation from MIT.[1]

Company history

[edit]

E Ink Corporation (or simply "E Ink") is a subsidiary of E Ink Holdings (EIH), a Taiwanese Holding Company (8069.TWO) manufacturer. They are the manufacturer and distributor of electrophoretic displays, a kind of electronic paper, that they market under the name E Ink. E Ink Corporation is headquartered in Billerica, Massachusetts. The company was co-founded in 1997 by Albert and Comiskey, along with Joseph Jacobson (professor in the MIT Media Lab), Jerome Rubin (LexisNexis co-founder), and Russ Wilcox.[9] Two years later, E Ink partnered with Philips to develop and market the technology. Jacobson and Comiskey are listed as inventors on the original patent filed in 1996.[6] Albert, Comiskey, and Jacobsen were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in May 2016.[10] In 2005, Philips sold the electronic paper business as well as its related patents to one of its primary business partners, Prime View International (PVI), a Hsinchu, Taiwan-based manufacturer.

At the E Ink Corporation, Comiskey led the development effort for E Ink's first generation of electronic ink,[11] while Albert developed the manufacturing methods used to make electronic ink displays in high volumes.[12] Wilcox played a variety of business roles and served as CEO from 2004 to 2009.[13]

Acquisition

[edit]On June 1, 2008, E Ink Corp. announced an initial agreement to be purchased by PVI (Prime View International, as seen from Company History) for $215 million, an amount that eventually reached US$450 million following negotiations.[14][15] E Ink was officially acquired on December 24, 2009. The purchase by PVI magnified the scale of production for the E Ink e-paper display, since Prime View also owned BOE Hydis Technology Co., Ltd and maintained a strategic partner relationship with Chi Mei Optoelectronics Corp. (now Chimei InnoLux Corporation, part of the Hon Hai-Foxconn Group). Foxconn is the sole ODM partner for Prime View's Netronix Inc., the supplier of E Ink panel e-readers, but the end-use products appear in various guises, e.g., as Bookeen, COOL-ER, PocketBook, etc.

PVI renamed itself E Ink Holdings Inc. after the purchase. In December 2012, E Ink acquired SiPix, a rival electrophoretic display company.[16][17][18]

Applications

[edit]

E Ink is made into a film and then integrated into electronic displays, enabling novel applications in phones, watches, magazines, wearables and e-readers, etc.[19][20][21][22]

The Motorola F3 was the first mobile phone to employ E Ink technology in its display to take advantage of the material's ultra-low power consumption. In addition, the Samsung Alias 2 uses this technology in its keypad in order to allow varying reader orientations.[23]

The October 2008 limited edition North American issue of Esquire was the first magazine cover to integrate E Ink. This cover featured flashing text. It was manufactured in Shanghai and was shipped refrigerated to the United States for binding. The E Ink was powered by a 90-day integrated battery supply.[21][24]

In July 2015, New South Wales Road and Maritime Services installed road traffic signs using E Ink in Sydney, Australia. The installed e-paper traffic signs represent the first use of E Ink in traffic signage.[25][26] Transport for London made trials of E Ink displays at bus stops to offer timetables, route maps and real-time travel information.[27] A Whole Foods store opened in 2016 with E Ink shelf labels that can update product info remotely.[28] E Ink Prism was announced in January 2015 at International CES and is the internal name for E Ink's bistable ink technology in a film that can dynamically change colors, patterns and designs with architectural products.[29] E Ink displays can also be made flexible.[30]

Commercial display products

[edit]E Ink has since partnered with various companies, including Sony, Ledger, Motorola and Amazon. E Ink's "Vizplex" technology is used by Sony Reader, MOTOFONE F3, Barnes & Noble Nook, Kindle, txtr Beagle, and Kobo eReader. E Ink's "Pearl" technology is claimed to have a 50% better contrast ratio. It is used by 2011-2012 Kindle models, Barnes & Noble Nook Simple Touch, Kobo Touch, and Sony PRS-T1. E Ink's "Carta" technology is used by reMarkable, Kindle Paperwhite (2nd and 3rd generation), Kindle Voyage, Kobo Glo HD, Kobo Aura H2O, and Kindle Oasis.

Versions or models of E Ink

[edit]

| 2007 | Vizplex |

|---|---|

| 2008 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | Pearl |

| 2011 | |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | Carta |

| 2014 | Carta HD |

| 2015 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2019 | |

| 2020 | |

| 2021 | Carta 1200 |

| 2022 | |

| 2023 | Carta 1300 |

E Ink Vizplex is the first generation of the E Ink displays. Vizplex was announced in May 2007.[31]

E Ink Pearl, announced in July 2010, is the second generation of E Ink displays. The updated Amazon Kindle DX was the first device announced to use the screen.[32] Amazon used this display technology in new Kindle models until the Paperwhite 2 refresh in 2013.[33] The basic Kindle with touch continued to use Pearl until 2022 when the Kindle 11 was upgraded past 167 dpi.[34] Sony also included this technology into its 2010 models of the Sony Reader PRS series.[35] This display is also used in the Nook Simple Touch,[36] Kobo eReader Touch,[37] Kobo Glo, Onyx Boox M90,[38] X61S[39] and Pocketbook Touch.[40]

E Ink Mobius is an E Ink display using a flexible plastic backplane, so it can resist small impacts and some flexing.[41] Products using this include Sony Digital Paper DPT-S1,[42] Pocketbook CAD Reader Flex,[43] Dasung Paperlike HD and Onyx Boox MAX 3.

E Ink Triton, announced in November 2010, is a color display that is easy to read in high light. The Triton is able to display 16 shades of gray, and 4,096 colors.[44] E Ink Triton is used in commercially available products such as the Hanvon color e-reader,[45] JetBook Color made by ectaco and PocketBook Color Lux made by PocketBook.

E Ink Triton 2 is the last generation of E Ink Triton color displays. The e-readers featuring it appeared in 2013. They include Ectaco Jetbook Color 2 and Pocketbook Color Lux.[46][47]

E Ink Carta, announced in January 2013 at International CES, features 768 by 1024 resolution on 6-inch displays, with 212 ppi pixel density.[48] Named Carta, it is used in the Kindle Paperwhite 2 (2013), the Pocketbook Touch Lux 3 (2015),[49] and the Kobo Nia (2020).

E Ink Carta HD features a 1080 by 1440 resolution on a 6" screen with 300 ppi. It is used in many eReaders including all new Kindle model lines since 2014 (Voyage, Oasis, Scribe) as well as the Paperwhite 3 (2015) and newer, Tolino Vision 2 (2014), Kobo Glo HD (2015),[50] Nook Glowlight Plus[51] (2015), Cybook Muse Frontlight, PocketBook Touch HD[52] (2016), PocketBook Touch HD 2 (2017), and the Kobo Clara HD[53] (2018).

The original E Ink Carta display was renamed to Carta 1000, and refinements in Carta 1100 and Carta 1200 improved response times and display contrast.[54] A later refinement in Carta 1250 improved response times and contrast again.[55]

E Ink Carta and Carta HD displays support Regal waveform technology, which reduces the need for page refreshes.[56]

The overall contrast in a product depends on the entire panel stack, including touch sensor and front light (when provided).[57]

E Ink Spectra is a three pigment display. The display uses microcups, each of which contains three pigments.[58] It is available for retail and electronic shelf tag labels. It is currently produced with black, white and red or black, white and yellow pigments.[59]

Advanced Color ePaper (ACeP) was announced at SID Display Week in May 2016. The display contains four pigments in each microcapsule or microcup thereby eliminating the need for a color filter overlay. The pigments used are cyan, magenta, yellow and white, enabling display of a full color gamut and up to 32,000 colors.[58][59] Initially targeted at the in-store signage market, with 20-inch displays with a resolution of 1600 by 2500 pixels at 150 ppi with a two-second refresh rate,[60] it began shipping for signage purposes in late 2018.[61] It is also being commercially manufactured for e-readers under the name E Ink Gallery 3. The first readers started shipping in 2023, however some planned e-readers were later postponed due to supply issues.[62]

E Ink Kaleido, originally announced in December 2019[63] as "Print Color", is the first of a new generation of color displays based on one of E Ink's greyscale displays with a color filter layer. E Ink Kaleido uses a plastic color filter layer, unlike the glass filter layer used in the E Ink Triton family of displays.[64] Kaleido Plus and Kaleido 3 were released in 2021[65] and 2023[66] respectively, further improving performance and pixel density.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Klein, Alec. "A New Printing Technology Sets Off a High-Stakes Race". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ Carmody, Tim (November 9, 2010). "How E Ink's Triton Color Displays Work, In E-Readers and Beyond". Wired. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "ePaper phones". www.e-ink-info.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ a b Platt, Charles. "Digital Ink by Charles Platt". Wired. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Joseph Jacobson Spotlight | National Inventors Hall of Fame". invent.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-05. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ a b US 5930026, Jacobson, Joseph M. & Comiskey, Barrett, "Nonemissive displays and piezoelectric power supplies therefor", published 1999-07-27, assigned to Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ Comiskey, Barrett; Albert, J. D.; Yoshizawa, Hidekazu; Jacobson, Joseph (1998-07-16). "An Electrophoretic Ink for All Printed Reflective Electronic Displays". Nature. 394 (6690): 253–255. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..253C. doi:10.1038/28349. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 204998708.

- ^ US 5961804, Jacobson, Joseph; Comiskey, Barrett & Albert, Jonathan, "Microencapsulated electrophoretic display", published 1999-10-05, assigned to Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ "E Ink's wild ride". Harvard Business School Alumni Bulletin. Sep 2009. Archived from the original on 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2020-11-08.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame announces 2016 inductees". Archived from the original on 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- ^ "The World Economic Forum Designates Technology Pioneers for 2002: Barrett Comiskey, Co-Founder of E Ink Corporation, Selected. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "J.D. Albert Spotlight | National Inventors Hall of Fame". invent.org. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Russ Wilcox Steps Down at E Ink---Smart Energy Venture Next? | Xconomy". Xconomy. March 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Russ Wilcox Steps Down at E Ink—Smart Energy Venture Next? Xconomy". Xconomy. March 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ "E-Ink's Sale Clears Path for Color Kindle in 2010". Fast Company. June 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ "E Ink Holdings - About Us". www.einkgroup.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- ^ "E Ink acquires SiPix, may dominate e-paper universe". Engadget. 4 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- ^ "EIH to acquire SiPix Technology". Digitimes.com. 2012-08-06. Archived from the original on 2012-08-08. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "Watches E Ink: Customer Showcase". www.eink.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-25. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Cell Phones E Ink". www.eink.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-12. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ a b Esquire's E-Ink Cover Archived 2014-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, Esquire.com website, September 8, 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ "All-new Kindle - Now with a Built-in Front Light - Amazon Official Site". www.amazon.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-25. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ "Motofone Makes Its Global Debut Introducing Stylish Connectivity For Everyone". E Ink Corporation (Press release). Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Esquire Becomes First Magazine To Merge Digital Technology With Printed Pages | Ford Motor Company Newsroom". Media.ford.com. 2008-07-21. Archived from the original on 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ^ "Sydney launches 'world's first' e-paper traffic signs". www.digitalsignagetoday.com. 2015-07-17. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ^ Bogle, Ariel (28 July 2015). "'World first' electronic ink traffic signs trialled in Australia". Mashable. Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ^ "London bus stops embrace e-paper", BBC News, 2015-12-22, archived from the original on 2017-02-26, retrieved 2017-01-05

- ^ "Thoughtfully simple". Oregon Local News. Archived from the original on 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ^ "E Ink Launches Prism, the World's First Dynamic Architecture Product Incorporating Color Changing Electronic Ink Technology | Business Wire". www.businesswire.com. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ^ "Flexible | E-Ink-Info". Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ Miller, Paul (2007-05-10). "E Ink Corp. announces "Vizplex" tech to speed, brighten displays". Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "E Ink explains the new Pearl display used in the updated Kindle DX". Engadget. July 2010. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ "Kindle Paperwhite 2 Has Much Improved Frontlight, But Difference with Carta Screen is Marginal". 3 October 2013.

- ^ "The new entry-level Kindle is the one to buy". 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Reader Touch Edition". Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ Noble, Barnes &. "NOOK eReader and Tablets". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Store, Rakuten Kobo eReader. "Rakuten Kobo eReader Store". Rakuten Kobo eReader Store. Archived from the original on 2018-07-30. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ "Domena onyx-boox.com jest utrzymywana na serwerach nazwa.pl". www.onyx-boox.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ "Onyx Boox X61S review (in Polish)". Archived from the original on 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ "The PocketBook Touch model is a device for reading which combines all the best and most important characteristics of a modern reader". pocketbook-int.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-05. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ^ "Types of displays of e-book readers". Archived from the original on 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ^ "Sony's found the perfect use for its $1,100 Digital Paper: HR forms". 22 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ "$574 Pocketbook CAD Reader Delayed Until Next Year, Will Have a 13.3" Mobius E-ink Screen". 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- ^ Triton (PDF) (press release), E Ink, archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-12, retrieved 2020-04-23

- ^ Taub, Eric A (November 7, 2010). "Color Comes to E Ink Screens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ Kozlowski, Michael (2013), Hands on with E-Ink Triton 2 and Prototype Front Lite Technology, good ereader, archived from the original on 2013-12-25, retrieved 2013-12-24

- ^ Kozlowski, Michael (2013), Review of the Pocketbook Color Lux eReader, Good ereader, archived from the original on 2013-12-25, retrieved 2013-12-24

- ^ "E Ink's future foretold at CES: Next-gen will be high-res, support color", PC world (video), archived from the original on 2017-01-19, retrieved 2020-04-23

- ^ "PocketBook Touch Lux 3 retains all flagship e-reader's traits, and has achieved an important enhancement – the latest E Ink Carta display with HD resolution (1024x758 pixels)". Pocketbook. Archived from the original on 2015-05-29.

- ^ "Amazon unveils high-res e-ink Kindle Voyage, new Fire tablet for Kids, updated HDX". ExtremeTech. September 18, 2014. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Noble, Barnes &. "NOOK Gowlight vs Kindle Paperwhite". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "Pocketbook Touch HD Review". goodereader.com. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Store, Rakuten Kobo eReader. "Kobo Clara HD". Rakuten Kobo eReader Store. Archived from the original on 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ "Electronic Ink Film". E Ink. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "E Ink, Wacom and Linfiny Announce Next-Generation Digital eNote Solutions With Android OS, Wacom's EMR Technology and the Latest E Ink Carta™ 1250". E Ink. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Nate Hoffelder (September 4, 2013) E-ink Announces New (4th-Gen) Screen Tech – Carta Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Groezinger, Nathan (26 June 2021). "Is Kobo Elipsa's New E Ink Carta 1200 Screen Just a Marketing Gimmick?". the-ebook-reader.com. Nathan Groezinger as sole proprietor. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Technology, Electronic Ink". E Ink. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Technology, Color". E Ink. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Diaz, Jon (2016-05-24). "E Ink Announces Advanced Color ePaper, a Breakthrough Technology for Color EPD Applications". BusinessWire. Archived from the original on 2016-05-25. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ "Colored E Ink is now shipping, but it still has a long way before it hits e-readers". The Verge. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-11-18. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ "Bunte Aussichten für 2023: PocketBook Viva mit neuester Farbtechnologie". PocketBook.de (in German). 2022-12-17.

- ^ "E Ink Releasing New "Print-Color" Screens for eReaders and Notebooks | The eBook Reader Blog". Blog.the-ebook-reader.com. 18 December 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- ^ "E Ink │ Color". www.eink.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "E Ink Releases Latest Generation Print Color Display: E Ink Kaleido™ Plus". www.eink.com. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "E Ink Launches E Ink Kaleido™ 3 Outdoor ePaper Technology". www.eink.com. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

External links

[edit]- Howstuffworks review on Electronic Ink

- Interview with Russ Wilcox, E Ink co-founder, vice-president and (from 2003 to 2010) CEO. 89 minutes.

_in_svg.svg/250px-Electronic_paper_(Side_view_of_Electrophoretic_display)_in_svg.svg.png)

_in_svg.svg/2000px-Electronic_paper_(Side_view_of_Electrophoretic_display)_in_svg.svg.png)