Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

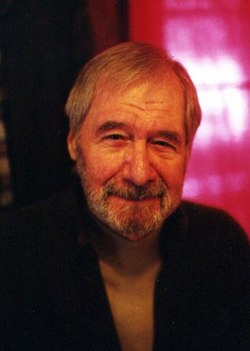

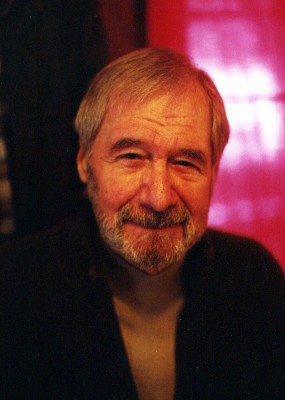

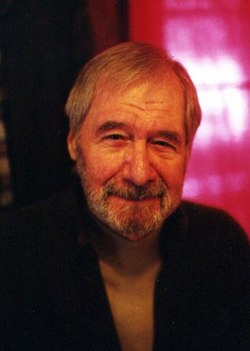

Evan Hunter

View on WikipediaEvan Hunter (born Salvatore Albert Lombino; October 15, 1926 – July 6, 2005) was an American author of crime and mystery fiction. He is best known as the author of the 87th Precinct novels, published under the pen name Ed McBain, which are considered staples of police procedural genre.

Key Information

His other notable works include The Blackboard Jungle, a semi-autobiographical novel about life in a troubled inner-city school, which was adapted into a hit 1955 film of the same name. He also wrote the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film The Birds, based on the Daphne du Maurier short story.

Hunter, who legally adopted that name in 1952, also used the pen names John Abbott, Curt Cannon, Hunt Collins, Ezra Hannon and Richard Marsten, among others.

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Salvatore Lombino was born and raised in New York City. He lived in East Harlem until age 12, when his family moved to the Bronx. He attended Olinville Junior High School (later Richard R. Green Middle School #113), then Evander Childs High School (now Evander Childs Educational Campus), before winning a New York Art Students League scholarship. Later, he was admitted as an art student at Cooper Union. Lombino served in the United States Navy during World War II and wrote several short stories while serving aboard a destroyer in the Pacific. However, none of these stories was published until after he had established himself as an author in the 1950s.

After the war, Lombino returned to New York and attended Hunter College, where he majored in English and psychology, with minors in dramatics and education, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1950.[2] He published a weekly column in the Hunter College newspaper as "S.A. Lombino". In 1981, Lombino was inducted into the Hunter College Hall of Fame, where he was honored for outstanding professional achievement.[3]

While looking to start a career as a writer, Lombino took a variety of jobs, including 17 days as a teacher at Bronx Vocational High School in September 1950. This experience would later form the basis for his novel The Blackboard Jungle (1954), written under the pen name Evan Hunter, which was adapted into the film Blackboard Jungle (1955).

In 1951, Lombino took a job as an executive editor for the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, working with authors such as Poul Anderson, Arthur C. Clarke, Lester del Rey, Richard S. Prather, and P.G. Wodehouse. He made his first professional short story sale the same year, a science-fiction tale titled "Welcome, Martians!", credited to S. A. Lombino.[4]

Name change and pen names

[edit]Soon after his initial sale, Lombino sold stories under the pen names Evan Hunter and Hunt Collins. The name Evan Hunter is generally believed to have been derived from two schools he attended, Evander Childs High School and Hunter College, although the author himself would never confirm that. (He did confirm that Hunt Collins was derived from Hunter College.) Lombino legally changed his name to Evan Hunter in May 1952, after an editor told him that a novel he wrote would sell more copies if credited to Evan Hunter than to S. A. Lombino. Thereafter, he used the name Evan Hunter both personally and professionally.

As Evan Hunter, he gained notice with his novel The Blackboard Jungle (1954) dealing with juvenile crime and the New York City public school system. The film adaptation followed in 1955.

During this era, Hunter also wrote a great deal of genre fiction. He was advised by his agents that publishing too much fiction under the Hunter byline, or publishing any crime fiction as Evan Hunter, might weaken his literary reputation. Consequently, during the 1950s Hunter used the pseudonyms Curt Cannon, Hunt Collins, and Richard Marsten for much of his crime fiction. A prolific author in several genres, Hunter also published approximately two dozen science fiction stories and four science-fiction novels between 1951 and 1956 under the names S. A. Lombino, Evan Hunter, Richard Marsten, D. A. Addams, and Ted Taine.

Ed McBain, his best known pseudonym, was first used with Cop Hater (1956), the first novel in the 87th Precinct crime series. Hunter revealed that he was McBain in 1958 but continued to use the pseudonym for decades, notably for the 87th Precinct series and the Matthew Hope detective series. He retired the pen names Addams, Cannon, Collins, Marsten, and Taine around 1960. From then on crime novels were generally attributed to McBain and other sorts of fiction to Hunter. Reprints of crime-oriented stories and novels written in the 1950s previously attributed to other pseudonyms were reissued under the McBain byline. Hunter stated that the division of names allowed readers to know what to expect: McBain novels had a consistent writing style, while Hunter novels were more varied.

Under the Hunter name, novels steadily appeared throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, including Come Winter (1973) and Lizzie (1984). Hunter was also successful as screenwriter for film and television. He wrote the screenplay for the Alfred Hitchcock film The Birds (1963), loosely adapted from Daphne du Maurier's eponymous 1952 novelette. Following The Birds, Hunter was again hired by Hitchcock to complete an in-progress script adapting Winston Graham's novel Marnie. However, Hunter and the director disagreed on how to treat the novel's rape scene, and the writer was sacked.[5] Hunter's other screenplays included Strangers When We Meet (1960), based on his own 1958 novel; and Fuzz (1972), based on his eponymous 1968 87th Precinct novel, which he had written as Ed McBain.

After having thirteen 87th Precinct novels published from 1956 to 1960, further 87th Precinct novels appeared at a rate of approximately one a year until his death. Additionally, NBC ran a police drama called 87th Precinct during the 1961–62 season, based on McBain's work.

From 1978 to 1998, McBain published a series about lawyer Matthew Hope; books in this series appeared every year or two, and usually had titles derived from well-known children's stories. For about a decade, from 1984 to 1994, Hunter published no fiction under his own name. In 2000, a novel called Candyland appeared that was credited to both Hunter and McBain. The two-part novel opened in Hunter's psychologically based narrative voice before switching to McBain's customary police procedural style.

Aside from McBain, Hunter used at least two other pseudonyms for his fiction after 1960: Doors (1975), which was originally attributed to Ezra Hannon before being reissued as a work by McBain, and Scimitar (1992), which was credited to John Abbott.

Hunter gave advice to other authors in his article "Dig in and get it done: no-nonsense advice from a prolific author (aka Ed McBain) on starting and finishing your novel". In it, he advised authors to "find their voice for it is the most important thing in any novel".[6]

Dean Hudson controversy

[edit]Hunter was long rumored to have written an unknown number of pornographic novels, as Dean Hudson, for William Hamling's publishing houses. Hunter adamantly and consistently denied writing any books as Hudson until he died. However, apparently his agent Scott Meredith sold books to Hamling's company as Hunter's work (for attribution as "Dean Hudson") and received payments for these books in cash. While notable, it is not definitive proof: Meredith almost certainly forwarded novels to Hamling by any number of authors, claiming these novels were by Hunter simply to make a sale. Ninety-three novels were published under the Hudson name from 1961 to 1969, and even the most avid proponents of the Hunter-as-Hudson theory do not believe Hunter is responsible for all 93.[7][8]

Personal life

[edit]He had three sons: Richard Hunter, an author, speaker, retired advisor to chief information officers on business value and risk issues, and harmonica player;[9][10] Mark Hunter, an academic, educator, investigative reporter, and author;[citation needed] and Ted Hunter, a painter, who died in 2006.[11]

Death

[edit]A heavy smoker for many decades, Hunter had three heart attacks over a number of years (his first in 1987) and needed heart surgery.[12] A precancerous lesion was found on his larynx in 1992. This was removed, but the cancer later returned. In 2005, Hunter died in Weston, Connecticut from laryngeal cancer. He was 78.[13]

Awards

[edit]- Edgar Award nomination for Best Short Story, "The Last Spin" (Manhunt, Sept. 1956)

- Edgar Award nomination Archived 2012-08-28 at the Wayback Machine for Best Motion Picture, The Birds (1964)

- Edgar Award nomination for Best Short Story, "Sardinian Incident" (Playboy, Oct. 1971)

- Grand Master, Mystery Writers of America (1986)

- Diamond Dagger, British Crime Writers Assn (first American recipient, 1998)

- Anthony Award nomination Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine for Best Series of the Century (2000)

- Edgar Award nomination for Best Novel, Money, Money, Money (2002)

Works

[edit]

Novels

[edit]| Year | Title | Credited author |

Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Find The Feathered Serpent | Evan Hunter | YA novel | |

| 1952 | The Evil Sleep! | Evan Hunter | Reprinted in 1956 as "So Nude, So Dead" under the name Richard Marsten[14] | |

| 1953 | Don't Crowd Me | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1953 | Danger: Dinosaurs! | Richard Marsten | YA novel | |

| 1953 | Rocket to Luna | Richard Marsten | YA novel | |

| 1954 | The Blackboard Jungle | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1954 | Runaway Black | Richard Marsten | Later credited as Ed McBain | |

| 1954 | Cut Me In | Hunt Collins | Later republished as The Proposition | |

| 1955 | Murder in the Navy | Richard Marsten | Later republished as Death of a Nurse by Ed McBain | |

| 1956 | Second Ending | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1956 | Cop Hater | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1956 | The Mugger | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1956 | The Pusher | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | 1960 film adaptation The Pusher |

| 1956 | Tomorrow's World | Hunt Collins | Later republished as Tomorrow And Tomorrow by Hunt Collins, and as Sphere by Ed McBain | |

| 1957 | The Con Man | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1957 | Killer's Choice | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1957 | Vanishing Ladies | Richard Marsten | Later republished as by Ed McBain | |

| 1957 | The Spiked Heel | Richard Marsten | ||

| 1958 | Strangers When We Meet | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1958 | The April Robin Murders | Craig Rice and Ed McBain | Hunter finished this novel started by Rice, using his McBain pen name. | |

| 1958 | Killer's Payoff | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1958 | Lady Killer | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1958 | Even The Wicked | Richard Marsten | Later republished as by Ed McBain | |

| 1958 | I'm Cannon—For Hire | Curt Cannon | Later revised and republished as The Gutter and the Grave by Ed McBain | |

| 1959 | A Matter of Conviction | Evan Hunter | 1961 film adaptation The Young Savages | |

| 1959 | The Remarkable Harry | Evan Hunter | Children's book | |

| 1959 | Big Man | Richard Marsten | Later republished as by Ed McBain | |

| 1959 | Killer's Wedge | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1959 | 'til Death | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1959 | King's Ransom | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1960 | Give the Boys a Great Big Hand | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1960 | The Heckler | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1960 | See Them Die | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1961 | Lady, Lady I Did It! | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1961 | Mothers And Daughters | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1961 | The Wonderful Button | Evan Hunter | Children's book | |

| 1962 | Like Love | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1963 | Ten Plus One | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1964 | Buddwing | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1964 | Ax | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1964 | He Who Hesitates | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1965 | Doll | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1965 | The Sentries | Ed McBain | ||

| 1965 | Me And Mr. Stenner | Evan Hunter | Children's book | |

| 1965 | Happy New Year, Herbie | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1966 | The Paper Dragon | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1966 | 80 Million Eyes | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1967 | A Horse's Head | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1968 | Last Summer | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1968 | Fuzz | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1969 | Sons | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1969 | Shotgun | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1970 | Jigsaw | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | This novel was adapted as the Columbo episode "Undercover" in 1994. |

| 1971 | Nobody Knew They Were There | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1971 | Hail, Hail the Gang's All Here | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1972 | Every Little Crook And Nanny | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1972 | Let's Hear It for the Deaf Man | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1972 | Seven | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1972 | Sadie When She Died | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1973 | Come Winter | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1973 | Hail to the Chief | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1974 | Streets Of Gold | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1974 | Bread | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1975 | Where There's Smoke | Ed McBain | ||

| 1975 | Blood Relatives | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1975 | Doors | Ezra Hannon | Later republished as by Ed McBain | |

| 1976 | So Long as You Both Shall Live | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | This novel was adapted as the Columbo episode "No Time to Die" in 1992. |

| 1976 | The Chisholms | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1976 | Guns | Ed McBain | ||

| 1977 | Long Time No See | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1977 | Goldilocks | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1979 | Walk Proud | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1979 | Calypso | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1980 | Ghosts | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1981 | Love, Dad | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1981 | Heat | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1981 | Rumpelstiltskin | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1982 | Beauty & The Beast | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1983 | Far From The Sea | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1983 | Ice | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1984 | Lizzie | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1984 | Lightning | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1984 | Jack & The Beanstalk | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1984 | And All Through the House | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | Short-story length work, issued (with illustrations) as a limited-edition novel. Reissued in 1994. |

| 1985 | Eight Black Horses | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1985 | Snow White & Rose Red | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1986 | Another Part of the City | Ed McBain | ||

| 1986 | Cinderella | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1987 | Poison | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1987 | Tricks | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1987 | Puss in Boots | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1988 | The House that Jack Built | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1989 | Lullaby | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1990 | Vespers | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1990 | Three Blind Mice | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | Adapted as a TV Movie in 2001, starring Brian Dennehy |

| 1991 | Downtown | Ed McBain | ||

| 1991 | Widows | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1992 | Kiss | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1992 | Mary, Mary | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1992 | Scimitar | John Abbott | ||

| 1993 | Mischief | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1994 | There Was A Little Girl | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1994 | Criminal Conversation | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1995 | Romance | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1996 | Privileged Conversation | Evan Hunter | ||

| 1996 | Gladly The Cross-Eyed Bear | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1997 | Nocturne | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 1998 | The Last Best Hope | Ed McBain | Matthew Hope | |

| 1999 | The Big Bad City | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2000 | Candyland | Evan Hunter and Ed McBain | Two-part novel that was billed as a "collaboration" between Hunter and his pseudonym. | |

| 2000 | Driving Lessons | Ed McBain | ||

| 2000 | The Last Dance | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2001 | Money, Money, Money | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2002 | The Moment She Was Gone | Evan Hunter | ||

| 2002 | Fat Ollie's Book | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2003 | The Frumious Bandersnatch | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2004 | Hark! | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct | |

| 2005 | Alice in Jeopardy | Ed McBain | ||

| 2005 | Fiddlers | Ed McBain | 87th Precinct |

Collections

[edit]- 1956: The Jungle Kids (Short Stories) (short stories by Evan Hunter)

- 1957: The Merry, Merry Christmas

- 1957: On the Sidewalk Bleeding

- 1960: The Last Spin & Other Stories

- 1962: The Empty Hours (87th Precinct short stories by Ed McBain)

- 1965: Happy New Year, Herbie (short stories by Evan Hunter)

- 1972: The Easter Man (a Play) And Six Stories (by Evan Hunter)

- 1982: The McBain Brief (Short stories by Ed McBain)

- 1988: McBain's Ladies (87th Precinct short stories by Ed McBain)

- 1992: McBain's Ladies, Too (87th Precinct short stories by Ed McBain)

- 2000: Barking at Butterflies & Other Stories (by Evan Hunter)

- 2000: Running from Legs (by Evan Hunter)

- 2006: Learning to Kill (short story collection by Ed McBain, published posthumously, featuring works written 1952-57)

Autobiographical

[edit]- 1998: Me & Hitch! (by Evan Hunter)

- 2005: Let's Talk (by Evan Hunter)

Plays

[edit]- The Easter Man (1964)

- The Conjuror (1969)

Screenplays

[edit]- Strangers When We Meet (1960)

- The Birds (1963)

- Fuzz (1972)

- Walk Proud (1979)

Teleplays

[edit]- The Chisholms, CBS miniseries starring Robert Preston (1979)

- The Legend of Walks Far Woman (1980)

- Dream West (1986)

As editor

[edit]- 2000: The Best American Mystery Stories (by Evan Hunter)

- 2005: Transgressions (collection of crime novellas by various authors edited by Ed McBain)

Incomplete novels

[edit]- Becca in Jeopardy (Near completion at the time of Hunter's death. Apparently to remain unpublished.)

Film adaptations

[edit]- Blackboard Jungle (1955) by Richard Brooks, from Blackboard Jungle

- The Young Savages (1961) by John Frankenheimer, from A Matter of Conviction

- High and Low (1963) by Akira Kurosawa, from King's Ransom

- Mister Buddwing (1966) by Delbert Mann, from Buddwing

- Last Summer (1969) by Frank Perry, from Last Summer

- Sans mobile apparent (1971) by Philippe Labro, from Ten Plus One

- Every Little Crook and Nanny (1972) by Cy Howard, from Every Little Crook and Nanny

- Blood Relatives (1978) by Claude Chabrol, from Blood Relatives

- Lonely Heart (1981) by Kon Ichikawa, from Lady, Lady, I Did It

References

[edit]- ^ Swirski, Peter (2016-07-15). American Crime Fiction: A Cultural History of Nobrow Literature as Art. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-30108-2.

- ^ "Evan Hunter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "Alumni Finding Aid" (PDF). Hunter.cuny.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ McBain, Ed, Learning To Kill, Harvest Books, 2006, pg. xi-xii

- ^ Hunter, Evan (1997). "Me and Hitch". Sight & Sound. 7 (6). British Film Institute: 25–37. ISSN 0037-4806.

- ^ "Dig in and get it done"; Evan Hunter. The Writer. Boston: Jun 2005. Vol. 118, Issue 6

- ^ Kemp, Earl (February 2006). "The Whitewash Jungle". Earl Kemp fanzine.

- ^ MacDonald, Erin E. (2012). Ed McBain/Evan Hunter: A Literary Companion. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2014-05-04.

- ^ "Richard Hunter, Former Distinguished VP Analyst". Gartner, Inc. Retrieved 2025-02-03.

- ^ "Richard Hunter's Bio". HunterHarp. Retrieved 2025-02-03.

- ^ "Ted hunter". Omnilexica. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ^ "In the Psychiatrist's Chair". BBC Radio 4. October 1998.

- ^ "Obituary". The New York Times. July 7, 2005.

- ^ McBain, Ed (14 July 2015). So Nude, So Dead. Titan Books (US, CA). ISBN 9781783293612. Retrieved 11 September 2018 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]- Evan Hunter at IMDb

- Official Evan Hunter Archived 2024-03-01 at the Wayback Machine and Ed McBain websites

- Evan Hunter and Ed McBain on Internet Book List

- Evan Hunter at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by Evan Hunter at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1993 interview, A Discussion with... National Authors on Tour TV Series

- 1995 interview, A Discussion with... National Authors on Tour TV Series

- 2001 interview with Leonard Lopate at WNYC (archived)

- 2005 interview with David Bianculli at NPR

Evan Hunter

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early life and family background

Salvatore Albert Lombino, later known as Evan Hunter, was born on October 15, 1926, in the kitchen of his parents' apartment in East Harlem, Manhattan, New York City.[2][5] He was the only child of Italian immigrant parents Charles E. Lombino, a substitute letter carrier who earned approximately $8 per week during the Great Depression and also played drums in local bands such as the Louisiana Five, and Marie Coppola Lombino, a mail-room clerk at the Harcourt, Brace publishing house.[6][5] The Lombino family lived at 120th Street between First and Second Avenues in East Harlem until Salvatore was 12 years old, after which they relocated to the Bronx in 1938 amid ongoing economic challenges.[6] During periods of hardship in the Depression era, Lombino stayed with his maternal grandparents, where his grandfather, a tailor, crafted his clothing.[6] These early experiences in working-class Italian-American neighborhoods of New York City shaped his familiarity with urban diversity and street life, which later influenced his writing.[2]Education and early professional experiences

Lombino graduated from Evander Childs High School in the Bronx in 1943 before briefly attending Cooper Union Art School from 1943 to 1944.[7] After his Navy service ended in 1946, he enrolled at Hunter College, majoring in English and psychology with minors in dramatics and education; he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1950.[8][9] Leveraging his education minor to secure an emergency teaching license, Lombino took a short-term position as a substitute English teacher at Bronx Vocational High School in September 1950, lasting approximately 17 days.[6][10] This brief tenure exposed him to the challenges of urban vocational education, which later shaped elements of his debut novel The Blackboard Jungle.[6][11] In 1951, Lombino joined the Scott Meredith Literary Agency in New York as an executive editor, a role that immersed him in manuscript evaluation, author development, and the mechanics of short story markets.[6][8] He supplemented his income with miscellaneous jobs, including performing as a pianist in a jazz band, while continuing to submit fiction to magazines.[2] These experiences provided practical insights into publishing and storytelling craft before his full transition to professional authorship.[6]Military service

Salvatore Albert Lombino, who later adopted the name Evan Hunter, enlisted in the United States Navy in 1944, shortly before his 18th birthday on October 15.[12] He served from 1944 to 1946 during the final years of World War II, primarily aboard a destroyer in the Pacific theater.[13] [14] During his naval service, Lombino began writing short stories, composing several while stationed at sea, though none were published at the time.[5] In June 1946, he declined a reenlistment bonus, opting instead to pursue civilian life and education upon discharge.[6] His military experience provided early discipline and material that influenced his later literary career, but no specific combat engagements or commendations are documented in primary accounts.[15]Personal life and relationships

Evan Hunter married Anita Melnick, a classmate from Hunter College, in 1949; the couple had three sons—Mark, Richard, and Ted—before divorcing.[16][17][2] His second marriage was to Mary Vann Finley (also referred to as Mary Vann Hughes) in 1973, which produced one stepdaughter and ended prior to his third marriage.[17][18] Hunter wed Dragica Dimitrijevic in September 1997; she was his wife at the time of his death on July 6, 2005, in Weston, Connecticut.[3][18]Literary Career

Adoption of pseudonyms and name change

Born Salvatore Albert Lombino on October 15, 1926, the author faced perceived barriers in the publishing industry due to his Italian heritage, prompting him to adopt a more Anglo-Saxon-sounding name to appeal to mainstream editors and readers.[19][2] In 1952, following advice from an editor that crediting a novel to "Evan Hunter" would boost sales, Lombino legally changed his name to Evan Hunter, using it for both personal and professional purposes thereafter.[8] This transition marked his shift from ethnic-associated identity to a neutral pseudonym that facilitated entry into literary markets skeptical of non-WASP authors.[2] Prior to the legal change, Lombino had already employed multiple pseudonyms for early short stories and novels across genres like science fiction, Westerns, and mysteries, including Hunt Collins, Richard Marsten, Curt Cannon, and Ezra Hannon, to maximize publication opportunities in pulp magazines and avoid oversaturating markets under one name.[20] These aliases allowed him to sell works rapidly in the competitive freelance market of the late 1940s and early 1950s, where outlets like Argosy and Manhunt demanded prolific output.[21] The most enduring pseudonym, Ed McBain, emerged in 1956 with the publication of Cop Hater, the debut of the 87th Precinct series, as Hunter sought to compartmentalize his "serious" literary fiction—written under his legal name—from the procedural crime novels he viewed as commercial genre work.[8] This separation preserved Evan Hunter's reputation for standalone novels like The Blackboard Jungle (1954), while Ed McBain became synonymous with ensemble police stories drawing from his experiences sketching courtroom scenes in Brooklyn.[22] Hunter maintained the dual identity rigorously, rarely acknowledging the connection publicly until later in his career, enabling distinct branding and readerships for each.[8]Breakthrough works and initial success

Evan Hunter achieved his literary breakthrough with the 1954 publication of The Blackboard Jungle by Simon & Schuster, a novel inspired by his brief tenure teaching English at New York City vocational high schools.[9] The work depicted the challenges of classroom discipline amid juvenile delinquency and racial tensions, resonating with postwar American concerns over youth culture and urban education.[9] It garnered immediate critical acclaim and commercial triumph as a bestseller, marking Hunter's transition from pulp fiction and short stories to mainstream recognition.[9] [8] The novel's success propelled Hunter's career, leading to its adaptation into a 1955 film directed by Richard Brooks, featuring Glenn Ford as the protagonist teacher and Sidney Poitier in a breakout role, which amplified its cultural impact through its soundtrack's inclusion of Bill Haley and His Comets' "Rock Around the Clock."[9] Building on this momentum, Hunter followed with Second Ending in 1956, a story of a fading musician's existential struggles, further solidifying his output of socially observant dramas.[9] By 1958, Strangers When We Meet reinforced his initial acclaim, chronicling suburban adultery and moral ambiguity in a narrative adapted by Hunter himself into a film starring Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak, released the following year.[9] This New York Times bestseller exemplified Hunter's skill in probing mid-century domestic tensions, contributing to his establishment as a versatile author capable of blending psychological depth with broad appeal before his deeper immersion in crime genres under pseudonyms.[9] [23]Development of the Ed McBain persona and police procedurals

Evan Hunter adopted the pseudonym Ed McBain in 1956 specifically for his police procedural novels, separating them from his literary fiction published under his legal name, which had gained prominence with The Blackboard Jungle (1954).[19] This distinction allowed Hunter to maintain distinct authorial voices: Evan Hunter for character-driven, socially conscious narratives, and McBain for terse, ensemble-focused crime stories emphasizing institutional routines over individual heroics.[8] Publishers at the time often restricted authors to one book per year per name to avoid market saturation, prompting the use of pseudonyms for prolific output.[24] The Ed McBain persona debuted with Cop Hater, the first 87th Precinct novel, published by Pocket Books in September 1956 following a 1955 contract for three such works.[25] Hunter developed the persona through meticulous research into New York Police Department operations, including visits to precincts and consultations with officers to capture authentic procedures, jargon, and bureaucratic dynamics—elements he contrasted with the lone-detective tropes of earlier American detective fiction.[26] This approach innovated the police procedural subgenre, pioneered in the U.S. by McBain's shift toward depicting an urban precinct as a collective entity, with rotating ensembles of detectives like Steve Carella and Meyer Meyer handling diverse crimes amid personal interruptions, administrative hurdles, and the city's multicultural grit.[27] McBain's style evolved rapidly in subsequent novels, such as The Mugger (November 1956) and The Pusher (December 1956), establishing a formula of short chapters, clipped dialogue, and procedural realism that prioritized causal chains of investigation over psychological introspection.[28] Hunter revealed his identity as McBain in 1958, yet continued the pseudonym exclusively for the series, which spanned 55 volumes until 2005, influencing later procedurals by grounding narratives in empirical depictions of law enforcement teamwork rather than stylized vigilantism.[14] The persona's enduring appeal lay in its causal fidelity to real-world policing, avoiding romanticization while acknowledging systemic flaws like interdepartmental rivalries and resource constraints.[29]Later career, screenplays, and collaborations

In the decades following his early successes, Evan Hunter sustained a high level of productivity, particularly through the ongoing 87th Precinct series under the Ed McBain pseudonym, releasing one or two installments annually from 1958 until his death in 2005, resulting in over 50 novels in the police procedural genre.[14] He also authored standalone works under his own name, including Criminal Conversation (1994), which examined ethnic tensions and infidelity in New York City, and The Moment She Was Gone (2004), a psychological thriller centered on sibling disappearance.[2] These later novels under Hunter often delved into social issues like immigration and family dynamics, diverging from the procedural focus of his McBain output while maintaining his emphasis on realistic character portrayals.[6] Hunter extended his influence into screenwriting, adapting material for prominent directors. He penned the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963), transforming Daphne du Maurier's short story into a narrative of avian terror in a coastal California town, earning an Oscar nomination for his contributions despite tensions with Hitchcock over script revisions.[30] Earlier, he scripted Strangers When We Meet (1960), directed by Richard Quine and starring Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak, based on his 1958 novel about suburban adultery.[3] Other credits include Fuzz (1972), a comedic crime film adaptation of his 1968 McBain novel featuring detectives battling a serial arsonist, and Walk Proud (1979), which he wrote and produced, depicting Chicano gang life in Los Angeles with a focus on redemption through music.[30] His work King's Ransom (1959, as Ed McBain) was adapted by Akira Kurosawa into High and Low (1963), a Japanese film exploring kidnapping and class disparity, though Hunter had no direct scripting role.[3] Notable among Hunter's collaborative efforts was Candyland (2001), presented as a joint novel by Evan Hunter and Ed McBain—pseudonyms of the same author—to contrast a protagonist's internal fantasies (Hunter's voice) with external realities (McBain's procedural style) in a tale of sexual compulsion and murder.[31] This structural innovation highlighted his versatility without involving external co-authors. Hunter also contributed to television, including episodes for the short-lived 87th Precinct series (1961–1962) based on his novels, though his later involvement shifted primarily to literary output.[30]Major Works

Novels under Evan Hunter

Evan Hunter, the legal name adopted by Salvatore Albert Lombino in 1952, published a diverse array of standalone novels distinct from his police procedurals under the Ed McBain pseudonym. These works often explored themes of urban alienation, adolescence, family dynamics, and social realism, drawing on Hunter's experiences as a teacher and New Yorker. Notable early successes include The Blackboard Jungle (1954), a semi-autobiographical depiction of high school teaching amid juvenile delinquency, which sold millions and was adapted into a 1955 film starring Glenn Ford and Sidney Poitier.[32][33] Similarly, Strangers When We Meet (1958) examined suburban infidelity and ambition, later adapted into a 1960 film with Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak.[32][33] Later novels shifted toward suspense and psychological drama, such as Last Summer (1968), which provoked controversy for its portrayal of teenage sexuality and was adapted into a 1969 film, and Mothers and Daughters (1961), a multi-generational saga spanning over 700 pages that became a bestseller.[32][33] Hunter's output under this name totaled over 20 novels, with many receiving film or TV adaptations, reflecting his versatility beyond genre fiction.[32] The following table lists key novels published under Evan Hunter, ordered by publication year:| Title | Year | Publisher (First Edition) |

|---|---|---|

| Don't Crowd Me | 1953 | Popular Library |

| The Blackboard Jungle | 1954 | Simon & Schuster |

| Second Ending | 1956 | Simon & Schuster |

| Strangers When We Meet | 1958 | Simon & Schuster |

| A Matter of Conviction | 1959 | Simon & Schuster |

| Mothers and Daughters | 1961 | Simon & Schuster |

| Happy New Year, Herbie | 1963 | Simon & Schuster |

| The Paper Dragon | 1966 | Delacorte Press |

| A Horse's Head | 1967 | Delacorte |

| Last Summer | 1968 | Doubleday |

| Sons | 1969 | Doubleday |

| Nobody Knew They Were There | 1971 | Doubleday |

| Every Little Crook and Nanny | 1972 | Doubleday |

| Come Winter | 1973 | Little Brown |

| Streets of Gold | 1974 | Harper & Row |

| The Chisholms | 1976 | Harper & Row |

| Love, Dad | 1981 | Crown Publishers |

| Far From the Sea | 1983 | Atheneum |

| Lizzie | 1984 | Arbor House |

| Criminal Conversation | 1994 | Warner Books |

| Privileged Conversation | 1996 | Warner Books |

| Candyland | 2001 | Simon & Schuster |

| The Moment She Was Gone | 2002 | Simon & Schuster |

87th Precinct series under Ed McBain

The 87th Precinct series comprises 55 police procedural novels authored by Evan Hunter under the pseudonym Ed McBain, spanning from Cop Hater in 1956 to Fiddlers in 2005.[26][34] The books depict the routine and high-stakes investigations of detectives in the fictional 87th Precinct of Isola, a stand-in for New York City divided into districts like Calm's Point and Riverhead, emphasizing ensemble teamwork over a single hero.[35][28] Central to the series is Detective Steve Carella, a dedicated family man and the precinct's lead investigator, whose deaf-mute wife Teddy appears recurrently, adding personal stakes to cases.[36] Supporting characters include Meyer Meyer, Carella's observant Jewish partner known for his bald pate and dry wit; the red-haired Cotton Hawes, distinguished by a white forelock from a past injury; rookie-turned-veteran Bert Kling, often entangled in romantic subplots; and others like Hal Willis and Arthur Brown, contributing to a rotating cast that reflects precinct diversity and dynamics.[37][36] The novels prioritize procedural realism, detailing authentic police methods such as squad room banter, forensic processes, and inter-departmental coordination, informed by McBain's consultations with law enforcement.[38] Early entries like The Mugger (1956) and The Pusher (1956) rapidly followed the debut, establishing a pattern of annual or near-annual releases that built a loyal readership through gritty urban crimes ranging from murders and heists to kidnappings.[28] Later volumes, such as Money, Money, Money (2001) and The Frumious Bandersnatch (2004), incorporated evolving societal issues like terrorism while maintaining the core focus on precinct operations.[39]| Key Novels | Publication Year |

|---|---|

| Cop Hater | 1956[40] |

| Killer's Wedge | 1959[28] |

| Hail, Hail, the Gang's All Here! | 1971[40] |

| Bread | 1974[40] |

| Fiddlers | 2005[37] |