Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chicano

View on Wikipedia

Chicano (masculine form) or Chicana (feminine form) is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans that emerged from the Chicano Movement.[1][2][3]

In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed among Hispanics in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of Indigenous descent (with many using the Nahuatl language or names).[4][5]

Chicano was used in a sense separate from Mexican American identity.[4][6][7][8] Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into mainstream American culture and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance.[9] The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.[10][11]

The Chicano Movement faltered by the mid-1970s as a result of external and internal pressures. It was under state surveillance, infiltration, and repression by U.S. government agencies, informants, and agents provocateurs, such as through the FBI's COINTELPRO.[12][13][14][15] The Chicano Movement also had a fixation on masculine pride and machismo that fractured the community through sexism toward Chicanas and homophobia toward queer Chicanos.[16][17][18]

In the 1980s, increased assimilation and economic mobility motivated many to embrace Hispanic identity in an era of conservatism.[19] The term Hispanic emerged from consultation between the U.S. government and Mexican-American political elites in the Hispanic Caucus of Congress.[20] They used the term to identify themselves and the community with mainstream American culture, depart from Chicanismo, and distance themselves from what they perceived as the "militant" Black Caucus.[21][22]

At the grassroots level, Chicano/as continued to build the feminist, gay and lesbian, and anti-apartheid movements, which kept the identity politically relevant.[19] After a decade of Hispanic dominance, Chicano student activism in the early 1990s recession and the anti-Gulf War movement revived the identity with a demand to expand Chicano studies programs.[19][23] Chicanas were active at the forefront, despite facing critiques from "movement loyalists", as they did in the Chicano Movement. Chicana feminists addressed employment discrimination, environmental racism, healthcare, sexual violence, and exploitation in their communities and in solidarity with the Third World.[24][25][26][27] Chicanas worked to "liberate her entire people"; not to oppress men, but to be equal partners in the movement.[28] Xicanisma, coined by Ana Castillo in 1994, called for Chicana/os to "reinsert the forsaken feminine into our consciousness",[29][30] to embrace one's Indigenous roots, and support Indigenous sovereignty.[31][30]

In the 2000s, earlier traditions of anti-imperialism in the Chicano Movement were expanded.[32] Building solidarity with undocumented immigrants became more important, despite issues of legal status and economic competitiveness sometimes maintaining distance between groups.[33][34] U.S. foreign interventions abroad were connected with domestic issues concerning the rights of undocumented immigrants in the United States.[32][35] Chicano/a consciousness increasingly became transnational and transcultural, thinking beyond and bridging with communities over political borders.[35] The identity was renewed based on Indigenous and decolonial consciousness, cultural expression, resisting gentrification, defense of immigrants, and the rights of women and queer people.[36][37] Xicanx identity also emerged in the 2010s, based on the Chicana feminist intervention of Xicanisma.[38][39][40]

| Part of a series on |

| Chicanos and Mexican Americans |

|---|

|

Etymology

[edit]

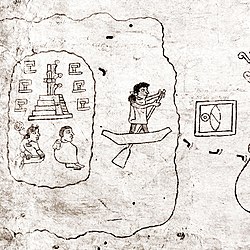

The etymology of the term Chicano is the subject of some debate by historians.[42] Some believe Chicano is a Spanish language derivative of an older Nahuatl word Mexitli ("Meh-shee-tlee"). Mexitli formed part of the expression Huitzilopochtlil Mexitli—a reference to the historic migration of the Mexica people from their homeland of Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. Mexitli is the root of the word Mexica, which refers to the Mexica people, and its singular form Mexihcatl (/meːˈʃiʔkat͡ɬ/). The x in Mexihcatl represents an /ʃ/ or sh sound in both Nahuatl and early modern Spanish, while the glottal stop in the middle of the Nahuatl word disappeared.[41]

The word Chicano may derive from the loss of the initial syllable of Mexicano (Mexican). According to Villanueva, "given that the velar (x) is a palatal phoneme (S) with the spelling (sh)," in accordance with the Indigenous phonological system of the Mexicas ("Meshicas"), it would become "Meshicano" or "Mechicano."[42] In this explanation, Chicano comes from the "xicano" in "Mexicano."[43] Some Chicanos replace the Ch with the letter X, or Xicano, to reclaim the Nahuatl sh sound. The first two syllables of Xicano are therefore in Nahuatl while the last syllable is Castilian.[41]

In Mexico's Indigenous regions, Indigenous people refer to members of the non-Indigenous majority[44] as mexicanos, referring to the modern nation of Mexico. Among themselves, the speaker identifies by their pueblo (village or tribal) identity, such as Mayan, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, or any of the other hundreds of Indigenous groups. A newly emigrated Nahuatl speaker in an urban center might have referred to his cultural relatives in this country, different from himself, as mexicanos, shortened to Chicanos or Xicanos.[41]

Usage of terms

[edit]Early recorded use

[edit]

The town of Chicana was shown on the Gutiérrez 1562 New World map near the mouth of the Colorado River, and is probably pre-Columbian in origin.[45] The town was again included on Desegno del Discoperto Della Nova Franza, a 1566 French map by Paolo Forlani. Roberto Cintli Rodríguez places the location of Chicana at the mouth of the Colorado River, near present-day Yuma, Arizona.[46] An 18th century map of the Nayarit Missions used the name Xicana for a town near the same location of Chicana, which is considered to be the oldest recorded usage of that term.[46]

A gunboat, the Chicana, was sold in 1857 to Jose Maria Carvajal to ship arms on the Rio Grande. The King and Kenedy firm submitted a voucher to the Joint Claims Commission of the United States in 1870 to cover the costs of this gunboat's conversion from a passenger steamer.[47] No explanation for the boat's name is known.

The Chicano poet and writer Tino Villanueva traced the first documented use of the term as an ethnonym to 1911, as referenced in a then-unpublished essay by University of Texas anthropologist José Limón.[48] Linguists Edward R. Simmen and Richard F. Bauerle report the use of the term in an essay by Mexican-American writer, Mario Suárez, published in the Arizona Quarterly in 1947.[49] There is ample literary evidence to substantiate that Chicano is a long-standing endonym, as a large body of Chicano literature pre-dates the 1950s.[48]

Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture.[50]

Reclaiming the term

[edit]

In the 1940s, "Chicano" was reclaimed by Pachuco youth as an expression of defiance to Anglo-American society.[50] At the time, Chicano was used among English and Spanish speakers as a classist and racist slur to refer to working class Mexican Americans in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods. In Mexico, the term was used with Pocho "to deride Mexicans living in the United States, and especially their U.S.-born children, for losing their culture, customs, and language."[51] Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio reported in 1930 that Chicamo (with an m) was used as a derogatory term by Hispanic Texans for recently arrived Mexican immigrants displaced during the Mexican Revolution in the beginning of the early 20th century.[52]

By the 1950s, Chicano referred to those who resisted total assimilation, while Pocho referred (often pejoratively) to those who strongly advocated for assimilation.[53] In his essay "Chicanismo" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures (2002), José Cuéllar, dates the transition from derisive to positive to the late 1950s, with increasing use by young Mexican-American high school students. These younger, politically aware Mexican Americans adopted the term "as an act of political defiance and ethnic pride", similar to the reclaiming of Black by African Americans.[54] The Chicano Movement during the 1960s and early 1970s played a significant role in reclaiming "Chicano," challenging those who used it as a term of derision on both sides of the Mexico-U.S. border.[51]

Demographic differences in the adoption of Chicano occurred at first. It was more likely to be used by males than females, and less likely to be used among those of higher socioeconomic status. Usage was also generational, with third-generation men more likely to use the word. This group was also younger, more political, and different from traditional Mexican cultural heritage.[55][56] Chicana was a similar classist term to refer to "[a] marginalized, brown woman who is treated as a foreigner and is expected to do menial labor and ask nothing of the society in which she lives."[57] Among Mexican Americans, Chicano and Chicana began to be viewed as a positive identity of self-determination and political solidarity.[58] In Mexico, Chicano may still be associated with a Mexican American person of low importance, class, and poor morals (similar to the terms Cholo, Chulo and Majo), indicating a difference in cultural views.[59][60][61]

Chicano Movement

[edit]

Chicano was widely reclaimed in the 1960s and 1970s during the Chicano Movement to assert a distinct ethnic, political, and cultural identity that resisted assimilation into the mainstream American culture, systematic racism and stereotypes, colonialism, and the American nation-state.[62] Chicano identity formed around seven themes: unity, economy, education, institutions, self-defense, culture, and political liberation, in an effort to bridge regional and class divisions.[63] The notion of Aztlán, a mythical homeland claimed to be located in the southwestern United States, mobilized Mexican Americans to take social and political action. Chicano became a unifying term for mestizos.[62] Xicano was also used in the 1970s.[64][65]

In the 1970s, Chicanos developed a reverence for machismo while also maintaining the values of their original platform. For instance, Oscar Zeta Acosta defined machismo as the source of Chicano identity, claiming that this "instinctual and mystical source of manhood, honor and pride... alone justifies all behavior."[16] Armando Rendón wrote in Chicano Manifesto (1971) that machismo was "in fact an underlying drive of the gathering identification of Mexican Americans... the essence of machismo, of being macho, is as much a symbolic principle for the Chicano revolt as it is a guideline for family life."[66]

From the beginning of the Chicano Movement, some Chicanas criticized the idea that machismo must guide the people and questioned if machismo was "indeed a genuinely Mexican cultural value or a kind of distorted view of masculinity generated by the psychological need to compensate for the indignities suffered by Chicanos in a white supremacist society."[17] Angie Chabram-Dernersesian found that most of the literature on the Chicano Movement focused on men and boys, while almost none focused on Chicanas. The omission of Chicanas and the machismo of the Chicano Movement led to a shift by the 1990s.[17]

Xicanisma

[edit]

Xicanisma was coined by Ana Castillo in Massacre of the Dreamers (1994) as a recognition of a shift in consciousness since the Chicano Movement and to reinvigorate Chicana feminism.[29] The aim of Xicanisma is not to replace patriarchy with matriarchy, but to create "a nonmaterialistic and nonexploitive society in which feminine principles of nurturing and community prevail"; where the feminine is reinserted into our consciousness rather than subordinated by colonization.[67][68] The X reflects the Sh sound in Mesoamerican languages (such as Tlaxcala, which is pronounced Tlash-KAH-lah),[69] and so marked this sound with a letter X.[41] More than a letter, the X in Xicanisma is also a symbol to represent being at a literal crossroads or otherwise embodying hybridity.[67][68]

Xicanisma acknowledges Indigenous survival after hundreds of years of colonization and the need to reclaim one's Indigenous roots while also being "committed to the struggle for liberation of all oppressed people", wrote Francesca A. López.[31] Activists like Guillermo Gómez-Peña, issued "a call for a return to the Amerindian roots of most Latinos as well as a call for a strategic alliance to give agency to Native American groups."[30] This can include one's Indigenous roots from Mexico "as well as those with roots centered in Central and South America," wrote Francisco Rios.[70] Castillo argued that this shift in language was important because "language is the vehicle by which we perceive ourselves in relation to the world".[68]

Among a minority of Mexican Americans, the term Xicanx may be used to refer to gender non-conformity. Luis J. Rodriguez states that "even though most US Mexicans may not use this term," that it can be important for gender non-conforming Mexican Americans.[6] Xicanx may destabilize aspects of the coloniality of gender in Mexican American communities.[72][73][74] Artist Roy Martinez states that it is not "bound to the feminine or masculine aspects" and that it may be "inclusive to anyone who identifies with it".[75] Some prefer the -e suffix Xicane in order to be more in-line with Spanish-speaking language constructs.[76]

Distinction from other terms

[edit]Mexican American

[edit]

In the 1930s, "community leaders promoted the term Mexican American to convey an assimilationist ideology stressing white identity," as noted by legal scholar Ian Haney López.[4] Lisa Y. Ramos argues that "this phenomenon demonstrates why no Black-Brown civil rights effort emerged prior to the 1960s."[78] Chicano youth rejected the previous generation's racial aspirations to assimilate into Anglo-American society and developed a "Pachuco culture that fashioned itself neither as Mexican nor American."[4]

In the Chicano Movement, possibilities for Black–brown unity arose: "Chicanos defined themselves as proud members of a brown race, thereby rejecting, not only the previous generation's assimilationist orientation, but their racial pretensions as well."[4] Chicano leaders collaborated with Black Power movement leaders and activists.[10][11] Mexican Americans insisted that Mexicans were white, while Chicanos embraced being non-white and the development of brown pride.[4]

Mexican American continued to be used by a more assimilationist faction who wanted to define Mexican Americans "as a white ethnic group that had little in common with African Americans."[77] Carlos Muñoz argues that the desire to separate themselves from Blackness and political struggle was rooted in an attempt to minimize "the existence of racism toward their own people, [believing] they could "deflect" anti-Mexican sentiment in society" through affiliating with the mainstream American culture.[77]

Hispanic

[edit]Etymologically deriving from the Spanish word "Hispano", referring to the Latin word Hispania, which was used for the Iberian Peninsula under the Roman Republic, the term Hispanic is an Anglicized translation of the Spanish word "Hispano". Hispano is commonly used in the Spanish speaking world when referring to "Hispanohablantes" (Spanish speakers), "Hispanoamerica" (Spanish-America) and "Hispanos" when referring to the greater social imaginary held by many people across the Americas who descend from Spanish families. The term Hispano is commonly used in the U.S. states of New Mexico, Texas, and Colorado, as well as used in Mexico and other Spanish-American countries when referring to the greater Spanish-speaking world, often referred to as "Latin America".

Following the decline of the Chicano Movement, Hispanic was first defined by the U.S. Federal Office of Management and Budget's (OMB) Directive No. 15 in 1977 as "a person of Mexican, Dominican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South America or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race."[21] The term was promoted by Mexican American political elites to encourage cultural assimilation into the mainstream culture and move away from Chicanismo. The rise of Hispanic identity paralleled the emerging era of political and cultural conservatism in the United States during the 1980s.[21][22]

Key members of the Mexican American political elite, all of whom were middle-aged men, helped popularize the term Hispanic among Mexican Americans. The term was picked up by electronic and print media. Laura E. Gómez conducted a series of interviews with these elites and found that one of the main reasons Hispanic was promoted was to move away from Chicano: "The Chicano label reflected the more radical political agenda of Mexican-Americans in the 1960s and 1970s, and the politicians who call themselves Hispanic today are the harbingers of a more conservative, more accommodationist politics."[22]

Gómez found that some of these elites promoted Hispanic to appeal to white American sensibilities, particularly in regard to separating themselves from Black political consciousness. Gómez records:[22]

Another respondent agreed with this position, contrasting his white colleagues' perceptions of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus with their perception of the Congressional Black Caucus. 'We certainly haven't been militant like the Black Caucus. We're seen as a power bloc—an ethnic power bloc striving to deal with mainstream issues.'[22]

In 1980, Hispanic was first made available as a self-identification on U.S. census forms. While Chicano also appeared on the 1980 U.S. census, it was only permitted to be selected as a subcategory underneath Spanish/Hispanic descent, which erased the possibility of Afro-Chicanos, Chicanos of Indigenous descent, and other Chicanos of color. Chicano did not appear on any subsequent census forms and Hispanic has remained.[79] Since then, Hispanic has widely been used by politicians and the media. For this reason, many Chicanos reject the term Hispanic.[80][81]

Other terms

[edit]Instead of or in addition to identifying as Chicano or any of its variations, some may prefer:

- Latino/a, also anglicized as "Latin." Some US Latinos use Latin as a gender neutral alternative.

- Latin American (especially if immigrant).

- Mexican; mexicano/mexicana

- "Brown"

- Mestizo; [insert racial identity X] mestizo (e.g. blanco mestizo); pardo.

- californiano (or californio) / californiana; nuevomexicano/nuevomexicana; tejano/tejana.

- Part/member of la Raza. (Internal identifier, Spanish for "the Race")

- American, solely.

Identity

[edit]

Chicano and Chicana identity reflects elements of ethnic, political, cultural and Indigenous hybridity.[82] These qualities of what constitutes Chicano identity may be expressed by Chicanos differently. Armando Rendón wrote in the Chicano Manifesto (1971), "I am Chicano. What it means to me may be different than what it means to you." Benjamin Alire Sáenz wrote "There is no such thing as the Chicano voice: there are only Chicano and Chicana voices."[80] The identity can be somewhat ambiguous (e.g. in the 1991 Culture Clash play A Bowl of Beings, in response to Che Guevara's demand for a definition of "Chicano", an "armchair activist" cries out, "I still don't know!").[83]

Many Chicanos understand themselves as being "neither from here, nor from there", as neither from the United States or Mexico.[84] Juan Bruce-Novoa wrote in 1990: "A Chicano lives in the space between the hyphen in Mexican-American."[84] Being Chicano/a may represent the struggle of being institutionally acculturated to assimilate into the Anglo-dominated society of the United States, yet maintaining the cultural sense developed as a Latin-American cultured U.S.-born Mexican child.[85] Rafael Pérez-Torres wrote, "one can no longer assert the wholeness of a Chicano subject ... It is illusory to deny the nomadic quality of the Chicano community, a community in flux that yet survives and, through survival, affirms itself."[86]

Ethnic identity

[edit]

Chicano is a way for Mexican Americans to assert ethnic solidarity and Brown Pride. Boxer Rodolfo Gonzales was one of the first to reclaim the term in this way. This Brown Pride movement established itself alongside the Black is Beautiful movement.[79][87] Chicano identity emerged as a symbol of pride in having a non-white and non-European image of oneself.[1] It challenged the U.S. census designation "Whites with Spanish Surnames" that was used in the 1950s.[79] Chicanos asserted ethnic pride at a time when Mexican assimilation into American culture was being promoted by the U.S. government. Ian Haney López argues that this was to "serve Anglo self-interest", who claimed Mexicans were white to try to deny racism against them.[88]

Alfred Arteaga argues that Chicano as an ethnic identity is born out of the European colonization of the Americas. He states that Chicano arose as hybrid ethnicity or race amidst colonial violence.[89] This hybridity extends beyond a previously generalized "Aztec" ancestry, since the Indigenous peoples of Mexico are a diverse group of nations and peoples.[89] A 2011 study found that 85 to 90% of maternal mtDNA lineages in Mexican Americans are Indigenous.[90] Chicano ethnic identity may involve more than just Indigenous and Spanish ancestry. It may also include African ancestry (as a result of Spanish slavery or runaway slaves from Anglo-Americans).[89] Arteaga concluded that "the physical manifestation of the Chicano, is itself a product of hybridity."[89]

Robert Quintana Hopkins argues that Afro-Chicanos are sometimes erased from the ethnic identity "because so many people uncritically apply the 'one drop rule' in the U.S. [which] ignores the complexity of racial hybridity."[91] Black and Chicano communities have engaged in close political movements and struggles for liberation, yet there have also been tensions between Black and Chicano communities.[92] This has been attributed to racial capitalism and anti-Blackness in Chicano communities.[92][93] Afro-Chicano rapper Choosey stated "there's a stigma that Black and Mexican cultures don't get along, but I wanted to show the beauty in being a product of both."[94]

Political identity

[edit]

Chicano political identity developed from a reverence of Pachuco resistance in the 1940s. Luis Valdez wrote that "Pachuco determination and pride grew through the 1950s and gave impetus to the Chicano Movement of the 1960s ... By then the political consciousness stirred by the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots had developed into a movement that would soon issue the Chicano Manifesto—a detailed platform of political activism."[95][96] By the 1960s, the Pachuco figure "emerged as an icon of resistance in Chicano cultural production."[97] The Pachuca was not regarded with the same status.[97] Catherine Ramírez credits this to the Pachuca being interpreted as a symbol of "dissident femininity, female masculinity, and, in some instances, lesbian sexuality".[97]

The political identity was founded on the principle that the U.S. nation-state had impoverished and exploited the Chicano people and communities. Alberto Varon argued that this brand of Chicano nationalism focused on the machismo subject in its calls for political resistance.[62] Chicano machismo was both a unifying and fracturing force. Cherríe Moraga argued that it fostered homophobia and sexism, which became obstacles to the Movement.[18] As the Chicano political consciousness developed, Chicanas, including Chicana lesbians of color brought attention to "reproductive rights, especially sterilization abuse [sterilization of Latinas], battered women's shelters, rape crisis centers, [and] welfare advocacy."[18] Chicana texts like Essays on La Mujer (1977), Mexican Women in the United States (1980), and This Bridge Called My Back (1981) have been relatively ignored even in Chicano Studies.[18] Sonia Saldívar-Hull argued that even when Chicanas have challenged sexism, their identities have been invalidated.[18]

Chicano political activist groups like the Brown Berets (1967–1972; 1992–Present) gained support in their protests of educational inequalities and demanding an end to police brutality.[98] They collaborated with the Black Panthers and Young Lords, which were founded in 1966 and 1968 respectively. Membership in the Brown Berets was estimated to have reached five thousand in over 80 chapters (mostly centered in California and Texas).[98] The Brown Berets helped organize the Chicano Blowouts of 1968 and the national Chicano Moratorium, which protested the high rate of Chicano casualties in the Vietnam War.[98] Police harassment, infiltration by federal agents provocateurs via COINTELPRO, and internal disputes led to the decline and disbandment of the Berets in 1972.[98] Sánchez, then a professor at East Los Angeles College, revived the Brown Berets in 1992 prompted by the high number of Chicano homicides in Los Angeles County, hoping to replace the gang life with the Brown Berets.[98]

Reies Tijerina, who was a vocal claimant to the rights of Latin Americans and Mexican Americans and a major figure of the early Chicano Movement, wrote: "The Anglo press degradized the word 'Chicano.' They use it to divide us. We use it to unify ourselves with our people and with Latin America."[99]

Cultural identity

[edit]

Chicano represents a cultural identity that is neither fully "American" or "Mexican." Chicano culture embodies the "in-between" nature of cultural hybridity.[100] Central aspects of Chicano culture include lowriding, hip hop, rock, graffiti art, theater, muralism, visual art, literature, poetry, and more. Mexican American celebrities, artists, and actors/actresses help bring Chicano culture to light and contribute to the growing influence it has on American pop culture. In modern-day America you can now find Chicanos in all types of professions and trades.[101] Notable subcultures include the Cholo, Pachuca, Pachuco, and Pinto subcultures. Chicano culture has had international influence in the form of lowrider car clubs in Brazil and England, music and youth culture in Japan, Māori youth enhancing lowrider bicycles and taking on cholo style, and intellectuals in France "embracing the deterritorializing qualities of Chicano subjectivity."[102]

As early as the 1930s, the precursors to Chicano cultural identity were developing in Los Angeles, California and the Southwestern United States. Former zoot suiter Salvador "El Chava" reflects on how racism and poverty forged a hostile social environment for Chicanos which led to the development of gangs: "we had to protect ourselves".[103] Barrios and colonias (rural barrios) emerged throughout southern California and elsewhere in neglected districts of cities and outlying areas with little infrastructure.[104] Alienation from public institutions made some Chicano youth susceptible to gang channels, who became drawn to their rigid hierarchical structure and assigned social roles in a world of government-sanctioned disorder.[105]

Pachuco culture, which probably originated in the El Paso-Juarez area,[106] spread to the borderland areas of California and Texas as Pachuquismo, which would eventually evolve into Chicanismo. Chicano zoot suiters on the west coast were influenced by Black zoot suiters in the jazz and swing music scene on the East Coast.[107] Chicano zoot suiters developed a unique cultural identity, as noted by Charles "Chaz" Bojórquez, "with their hair done in big pompadours, and "draped" in tailor-made suits, they were swinging to their own styles. They spoke Cálo, their own language, a cool jive of half-English, half-Spanish rhythms. [...] Out of the zootsuiter experience came lowrider cars and culture, clothes, music, tag names, and, again, its own graffiti language."[103] San Antonio–based Chicano artist Adan Hernandez regarded pachucos as "the coolest thing to behold in fashion, manner, and speech."[106] As described by artist Carlos Jackson, "Pachuco culture remains a prominent theme in Chicano art because the contemporary urban cholo culture" is seen as its heir.[107]

Many aspects of Chicano culture like lowriding cars and bicycles have been stigmatized and policed by Anglo Americans who perceive Chicanos as "juvenile delinquents or gang members" for their embrace of nonwhite style and cultures, much as they did Pachucos.[108] These negative societal perceptions of Chicanos were amplified by media outlets such as the Los Angeles Times.[108] Luis Alvarez remarks how negative portrayals in the media served as a tool to advocate for increased policing of Black and Brown male bodies in particular: "Popular discourse characterizing nonwhite youth as animal-like, hypersexual, and criminal marked their bodies as "other" and, when coming from city officials and the press, served to help construct for the public a social meaning of African Americans and Mexican American youth [as, in their minds, justifiably criminalized]."[108]

Chicano rave culture in southern California provided a space for Chicanos to partially escape criminalization in the 1990s. Artist and archivist Guadalupe Rosales states that "a lot of teenagers were being criminalized or profiled as criminals or gangsters, so the party scene gave access for people to escape that".[109] Numerous party crews, such as Aztek Nation, organized events and parties would frequently take place in neighborhood backyards, particularly in East and South Los Angeles, the surrounding valleys, and Orange County.[110] By 1995, it was estimated that over 500 party crews were in existence. They laid the foundations for "an influential but oft-overlooked Latin dance subculture that offered community for Chicano ravers, queer folk, and other marginalized youth."[110] Ravers used map points techniques to derail police raids. Rosales states that a shift occurred around the late 1990s and increasing violence affected the Chicano party scene.[109]

Indigenous identity

[edit]

Chicano identity functions as a way to reclaim one's Indigenous American, and often Indigenous Mexican, ancestry—to form an identity distinct from European identity, despite some Chicanos being of partial European descent—as a way to resist and subvert colonial domination.[86] Rather than part of European American culture, Alicia Gasper de Alba referred to Chicanismo as an "alter-Native culture, an Other American culture Indigenous to the land base now known as the West and Southwest of the United States."[111] While influenced by settler-imposed systems and structures, Alba refers to Chicano culture as "not immigrant but native, not foreign but colonized, not alien but different from the overarching hegemony of white America."[111]

The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán (1969) drew from Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth (1961). In Wretched, Fanon stated: "the past existence of an Aztec civilization does not change anything very much in the diet of the Mexican peasant today", elaborating that "this passionate search for a national culture which existed before the colonial era finds its legitimate reason in the anxiety shared by native intellectuals to shrink away from that of Western culture in which they all risk being swamped ... the native intellectuals, since they could not stand wonderstruck before the history of today's barbarity, decided to go back further and to delve deeper down; and, let us make no mistake, it was with the greatest delight that they discovered that there was nothing to be ashamed of in the past, but rather dignity, glory, and solemnity."[86]

The Chicano Movement adopted this perspective through the notion of Aztlán—a mythic Aztec homeland which Chicanos used as a way to connect themselves to a precolonial past, before the time of the "'gringo' invasion of our lands."[86] Chicano scholars have described how this functioned as a way for Chicanos to reclaim a diverse or imprecise Indigenous past; while recognizing how Aztlán promoted divisive forms of Chicano nationalism that "did little to shake the walls and bring down the structures of power as its rhetoric so firmly proclaimed".[86] As stated by Chicano historian Juan Gómez-Quiñones, the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was "stripped of what radical element it possessed by stressing its alleged romantic idealism, reducing the concept of Aztlán to a psychological ploy ... all of which became possible because of the Plan's incomplete analysis which, in turn, allowed it ... to degenerate into reformism."[86]

While acknowledging its romanticized and exclusionary foundations, Chicano scholars like Rafael Pérez-Torres state that Aztlán opened a subjectivity which stressed a connection to Indigenous peoples and cultures at a critical historical moment in which Mexican-Americans and Mexicans were "under pressure to assimilate particular standards—of beauty, of identity, of aspiration. In a Mexican context, the pressure was to urbanize and Europeanize ... "Mexican-Americans" were expected to accept anti-indigenous discourses as their own."[86] As Pérez-Torres concludes, Aztlán allowed "for another way of aligning one's interests and concerns with community and with history ... though hazy as to the precise means in which agency would emerge, Aztlán valorized a Chicanismo that rewove into the present previously devalued lines of descent."[86] Romanticized notions of Aztlán have declined among some Chicanos, who argue for a need to reconstruct the place of Indigeneity in relation to Chicano identity.[112][113]

Danza Azteca grew popular in the U.S. with the rise of the Chicano Movement, which inspired some "Latinos to embrace their ethnic heritage and question the Eurocentric norms forced upon them."[114] The use of pre-contact Aztec cultural elements has been critiqued by some Chicanos who stress a need to represent the diversity of Indigenous ancestry among Chicanos.[89][115] Patrisia Gonzales portrays Chicanos as descendants of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico who have been displaced by colonial violence, positioning them as "detribalized Indigenous peoples and communities."[116] Roberto Cintli Rodríguez describes Chicanos as "de-Indigenized," which he remarks occurred "in part due to religious indoctrination and a violent uprooting from the land", detaching millions of people from maíz-based cultures throughout the greater Mesoamerican region.[117][118] Rodríguez asks how and why "peoples who are clearly red or brown and undeniably Indigenous to this continent have allowed ourselves, historically, to be framed by bureaucrats and the courts, by politicians, scholars, and the media as alien, illegal, and less than human."[119]

Gloria E. Anzaldúa has addressed Chicano's detribalization: "In the case of Chicanos, being 'Mexican' is not a tribe. So in a sense Chicanos and Mexicans are 'detribalized'. We don't have tribal affiliations but neither do we have to carry ID cards establishing tribal affiliation."[120] Anzaldúa recognized that "Chicanos, people of color, and 'whites'" have often chosen "to ignore the struggles of Native people even when it's right in our caras (faces)," expressing disdain for this "willful ignorance".[120] She concluded that "though both "detribalized urban mixed bloods" and Chicanos are recovering and reclaiming, this society is killing off urban mixed bloods through cultural genocide, by not allowing them equal opportunities for better jobs, schooling, and health care."[120] Inés Hernández-Ávila argued that Chicanos should recognize and reconnect with their roots "respectfully and humbly" while also validating "those peoples who still maintain their identity as original peoples of this continent" in order to create radical change capable of "transforming our world, our universe, and our lives".[121]

Political aspects

[edit]Anti-imperialism and international solidarity

[edit]

During World War II, Chicano youth were targeted by white servicemen, who despised their "cool, measured indifference to the war, as well as an increasingly defiant posture toward whites in general".[123] Historian Robin Kelley states that this "annoyed white servicemen to no end".[124] During the Zoot Suit Riots (1943), white rage erupted in Los Angeles, which "became the site of racist attacks on Black and Chicano youth, during which white soldiers engaged in what amounted to a ritualized stripping of the zoot."[124][123] Zoot suits were a symbol of collective resistance among Chicano and Black youth against city segregation and fighting in the war. Many Chicano and Black zoot-suiters engaged in draft evasion because they felt it was hypocritical for them to be expected to "fight for democracy" abroad yet face racism and oppression daily in the U.S.[125]

This galvanized Chicano youth to focus on anti-war activism, "especially influenced by the Third World movements of liberation in Asia, Africa, and Latin America." Historian Mario T. García reflects that "these anti-colonial and anti-Western movements for national liberation and self-awareness touched a historical nerve among Chicanos as they began to learn that they shared some similarities with these Third World struggles."[122] Chicano poet Alurista argued that "Chicanos cannot be truly free until they recognize that the struggle in the United States is intricately bound with the anti-imperialist struggle in other countries."[126] The Cuban Revolution (1953–1959) led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara was particularly influential to Chicanos, as noted by García, who notes that Chicanos viewed the revolution as "a nationalist revolt against 'Yankee imperialism' and neo-colonialism."[122][127]

In the 1960s, the Chicano Movement brought "attention and commitment to local struggles with an analysis and understanding of international struggles".[128] Chicano youth organized with Black, Latin American, and Filipino activists to form the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), which fought for the creation of a Third World college.[129] During the Third World Liberation Front strikes of 1968, Chicano artists created posters to express solidarity.[129] Chicano poster artist Rupert García referred to the place of artists in the movement: "I was critical of the police, of capitalist exploitation. I did posters of Che, of Zapata, of other Third World leaders. As artists, we climbed down from the ivory tower."[130] Learning from Cuban poster makers of the post-revolutionary period, Chicano artists "incorporated international struggles for freedom and self-determination, such as those of Angola, Chile, and South Africa", while also promoting the struggles of Indigenous people and other civil rights movements through Black-brown unity.[129] Chicanas organized with women of color activists to create the Third World Women's Alliance (1968–1980), representing "visions of liberation in third world solidarity that inspired political projects among racially and economically marginalized communities" against U.S. capitalism and imperialism.[24]

The Chicano Moratorium (1969–1971) against the Vietnam War was one of the largest demonstrations of Mexican-Americans in history,[131] drawing over 30,000 supporters in East L.A. Draft evasion was a form of resistance for Chicano anti-war activists such as Rosalio Muñoz, Ernesto Vigil, and Salomon Baldengro. They faced a felony charge—a minimum of five years prison time, $10,000, or both.[132] In response, Munoz wrote "I declare my independence of the Selective Service System. I accuse the government of the United States of America of genocide against the Mexican people. Specifically, I accuse the draft, the entire social, political, and economic system of the United States of America, of creating a funnel which shoots Mexican youth into Vietnam to be killed and to kill innocent men, women, and children...."[133] Rodolfo Corky Gonzales expressed a similar stance: "My feelings and emotions are aroused by the complete disregard of our present society for the rights, dignity, and lives of not only people of other nations but of our own unfortunate young men who die for an abstract cause in a war that cannot be honestly justified by any of our present leaders."[134]

Anthologies such as This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) were produced in the late 1970s and early 80s by writers who identified as lesbians of color, including Cherríe Moraga, Pat Parker, Toni Cade Bambara, Chrystos (self-identified claim of Menominee ancestry), Audre Lorde, Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Cheryl Clarke, Jewelle Gomez, Kitty Tsui, and Hattie Gossett, who developed a poetics of liberation. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press and Third Woman Press, founded in 1979 by Chicana feminist Norma Alarcón, provided sites for the production of women of color and Chicana literatures and critical essays. While first world feminists focused "on the liberal agenda of political rights", Third World feminists "linked their agenda for women's rights with economic and cultural rights" and unified together "under the banner of Third World solidarity".[24] Maylei Blackwell identifies that this internationalist critique of capitalism and imperialism forged by women of color has yet to be fully historicized and is "usually dropped out of the false historical narrative".[24]

In the 1980s and 90s, Central American activists influenced Chicano leaders. The Mexican American Legislative Caucus (MALC) supported the Esquipulas Peace Agreement in 1987, standing in opposition to Contra aid. Al Luna criticized Reagan and American involvement while defending Nicaragua's Sandinista-led government: "President Reagan cannot credibly make public speeches for peace in Central America while at the same time advocating for a three-fold increase in funding to the Contras."[135] The Southwest Voter Research Initiative (SVRI), launched by Chicano leader Willie Velásquez, intended to educate Chicano youth about Central and Latin American political issues. In 1988, "there was no significant urban center in the Southwest where Chicano leaders and activists had not become involved in lobbying or organizing to change U.S. policy in Nicaragua."[135] In the early 1990s, Cherríe Moraga urged Chicano activists to recognize that "the Anglo invasion of Latin America [had] extended well beyond the Mexican/American border" while Gloria E. Anzaldúa positioned Central America as the primary target of a U.S. interventionism that had murdered and displaced thousands. However, Chicano solidarity narratives of Central Americans in the 1990s tended to center themselves, stereotype Central Americans, and filter their struggles "through Chicana/o struggles, histories, and imaginaries."[136]

Chicano activists organized against the Gulf War (1990–91). Raul Ruiz of the Chicano Mexican Committee against the Gulf War stated that U.S. intervention was "to support U.S. oil interests in the region."[137] Ruiz expressed, "we were the only Chicano group against the war. We did a lot of protesting in L.A. even though it was difficult because of the strong support for the war and the anti-Arab reaction that followed ... we experienced racist attacks [but] we held our ground."[137] The end of the Gulf War, along with the Rodney King Riots, were crucial in inspiring a new wave of Chicano political activism.[138] In 1994, one of the largest demonstrations of Mexican Americans in the history of the United States occurred when 70,000 people, largely Chicanos and Latinos, marched in Los Angeles and other cities to protest Proposition 187, which aimed to cut educational and welfare benefits for undocumented immigrants.[139][140][141]

In 2004, Mujeres against Militarism and the Raza Unida Coalition sponsored a Day of the Dead vigil against militarism within the Latino community, addressing the War in Afghanistan (2001–) and the Iraq War (2003–2011) They held photos of the dead and chanted "no blood for oil." The procession ended with a five-hour vigil at Tia Chucha's Centro Cultural. They condemned "the Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (JROTC) and other military recruitment programs that concentrate heavily in Latino and African American communities, noting that JROTC is rarely found in upper-income Anglo communities."[142] Rubén Funkahuatl Guevara organized a benefit concert for Latin@s Against the War in Iraq and Mexamérica por la Paz at Self-Help Graphics against the Iraq War. Although the events were well-attended, Guevara stated that "the Feds know how to manipulate fear to reach their ends: world military dominance and maintaining a foothold in an oil-rich region were their real goals."[143]

Labor organizing against capitalist exploitation

[edit]

Chicano and Mexican labor organizers played an active role in notable labor strikes since the early 20th century including the 1903 Oxnard strike, Pacific Electric Railway strike of 1903, 1919 Streetcar Strike of Los Angeles, Cantaloupe strike of 1928, California agricultural strikes (1931–1941), and the Ventura County agricultural strike of 1941,[145] endured mass deportations as a form of strikebreaking in the Bisbee Deportation of 1917 and Mexican Repatriation (1929–1936), and experienced tensions with one another during the Bracero program (1942–1964).[144] Although organizing laborers were harassed, sabotaged, and repressed, sometimes through warlike tactics from capitalist owners[146][147] who engaged in coervice labor relations and collaborated with and received support from local police and community organizations, Chicano and Mexican workers, particularly in agriculture, have been engaged in widespread unionization activities since the 1930s.[148][149]

Prior to unionization, agricultural workers, many of whom were undocumented aliens, worked in dismal conditions. Historian F. Arturo Rosales recorded a Federal Project Writer of the period, who stated: "It is sad, yet true, commentary that to the average landowner and grower in California the Mexican was to be placed in much the same category with ranch cattle, with this exception–the cattle were for the most part provided with comparatively better food and water and immeasurably better living accommodations."[148] Growers used cheap Mexican labor to reap bigger profits and, until the 1930s, perceived Mexicans as docile and compliant with their subjugated status because they "did not organize troublesome labor unions, and it was held that he was not educated to the level of unionism".[148] As one grower described, "We want the Mexican because we can treat them as we cannot treat any other living man ... We can control them by keeping them at night behind bolted gates, within a stockade eight feet high, surrounded by barbed wire ... We can make them work under armed guards in the fields."[148]

Unionization efforts were initiated by the Confederación de Uniones Obreras (Federation of Labor Unions) in Los Angeles, with twenty-one chapters quickly extending throughout southern California, and La Unión de Trabajadores del Valle Imperial (Imperial Valley Workers' Union). The latter organized the Cantaloupe strike of 1928, in which workers demanded better working conditions and higher wages, but "the growers refused to budge and, as became a pattern, local authorities sided with the farmers and through harassment broke the strike".[148] Communist-led organizations such as the Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union (CAWIU) supported Mexican workers, renting spaces for cotton pickers during the cotton strikes of 1933 after they were thrown out of company housing by growers.[149] Capitalist owners used "red-baiting" techniques to discredit the strikes through associating them with communists. Chicana and Mexican working women showed the greatest tendency to organize, particularly in the Los Angeles garment industry with the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, led by anarchist Rose Pesotta.[148]

During World War II, the government-funded Bracero program (1942–1964) hindered unionization efforts.[148] In response to the California agricultural strikes and the 1941 Ventura County strike of Chicano and Mexican, as well as Filipino, lemon pickers/packers, growers organized the Ventura County Citrus Growers Committee (VCCGC) and launched a lobbying campaign to pressure the U.S. government to pass laws to prohibit labor organizing. VCCGC joined with other grower associations, forming a powerful lobbying bloc in Congress, and worked to legislate for (1) a Mexican guest workers program, which would become the Bracero program, (2) laws prohibiting strike activity, and (3) military deferments for pickers. Their lobbying efforts were successful: unionization among farmworkers was made illegal, farmworkers were excluded from minimum wage laws, and the usage of child labor by growers was ignored. In formerly active areas, such as Santa Paula, union activity stopped for over thirty years as a result.[145]

When World War II ended, the Bracero program continued. Legal anthropologist Martha Menchaca states that this was "regardless of the fact that massive quantities of crops were no longer needed for the war effort ... after the war, the braceros were used for the benefit of the large-scale growers and not for the nation's interest." The program was extended for an indefinite period in 1951.[145] In the mid-1940s, labor organizer Ernesto Galarza founded the National Farm Workers Union (NFWU) in opposition to the Bracero Program, organizing a large-scale 1947 strike against the Di Giorgio Fruit Company in Arvin, California. Hundreds of Mexican, Filipino, and white workers walked out and demanded higher wages. The strike was broken by the usual tactics, with law enforcement on the side of the owners, evicting strikers and bringing in undocumented workers as strikebreakers. The NFWU folded, but served as a precursor to the United Farm Workers Union led by César Chávez.[148] By the 1950s, opposition to the Bracero program had grown considerably, as unions, churches, and Mexican-American political activists raised awareness about the effects it had on American labor standards. On December 31, 1964, the U.S. government conceded and terminated the program.[145]

Following the closure of the Bracero program, domestic farmworkers began to organize again because "growers could not longer maintain the peonage system" with the end of imported laborers from Mexico.[145] Labor organizing formed part of the Chicano Movement via the struggle of farmworkers against depressed wages and working conditions. César Chávez began organizing Chicano farmworkers in the early 1960s, first through the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) and then merging the association with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), an organization of mainly Filipino workers, to form the United Farm Workers. The labor organizing of Chávez was central to the expansion of unionization throughout the United States and inspired the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), under the leadership of Baldemar Velásquez, which continues today.[150] Farmworkers collaborated with local Chicano organizations, such as in Santa Paula, California, where farmworkers attended Brown Berets meetings in the 1970s and Chicano youth organized to improve working conditions and initiate an urban renewal project on the eastside of the city.[151]

Although Mexican and Chicano workers, organizers, and activists organized for decades to improve working conditions and increase wages, some scholars characterize these gains as minimal. As described by Ronald Mize and Alicia Swords, "piecemeal gains in the interests of workers have had very little impact on the capitalist agricultural labor process, so picking grapes, strawberries, and oranges in 1948 is not so different from picking those same crops in 2008."[146] U.S. agriculture today remains totally reliant on Mexican labor, with Mexican-born individuals now constituting about 90% of the labor force.[152]

Struggles in the education system

[edit]

Chicanos often endure struggles in the U.S. education system, such as being erased in curriculums and devalued as students.[154][155] Some Chicanos identify schools as colonial institutions that exercise control over colonized students by teaching Chicanos to idolize the American culture and develop a negative self-image of themselves and their worldviews.[154][155] School segregation between Mexican and white students was not legally ended until the late 1940s.[156] In Orange County, California, 80% of Mexican students could only attend schools that taught Mexican children manual education, or gardening, bootmaking, blacksmithing, and carpentry for Mexican boys and sewing and homemaking for Mexican girls.[156] White schools taught academic preparation.[156] When Sylvia Mendez was told to attend a Mexican school, her parents brought suit against the court in Mendez vs. Westminster (1947) and won.[156]

Although legal segregation had been successfully challenged, de facto or segregation-in-practice continued in many areas.[156] Schools with primarily Mexican American enrollment were still treated as "Mexican schools" much as before the legal overturning of segregation.[156] Mexican American students were still treated poorly in schools.[156] Continued bias in the education system motivated Chicanos to protest and use direct action, such as walkouts, in the 1960s.[154][155] On March 5, 1968, the Chicano Blowouts at East Los Angeles High School occurred as a response to the racist treatment of Chicano students, an unresponsive school board, and a high dropout rate. It became known as "the first major mass protest against racism undertaken by Mexican-Americans in the history of the United States."[15]

Sal Castro, a Chicano social science teacher at the school was arrested and fired for inspiring the walkouts. It was led by Harry Gamboa Jr. who was named "one of the hundred most dangerous and violent subversives in the United States" for organizing the student walkouts. The day prior, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sent out a memo to law enforcement to place top priority on "political intelligence work to prevent the development of nationalist movements in minority communities".[15] Chicana activist Alicia Escalante protested Castro's dismissal: "We in the Movement will at least be able to hold our heads up and say that we haven't submitted to the gringo or to the pressures of the system. We are brown and we are proud. I am at least raising my children to be proud of their heritage, to demand their rights, and as they become parents they too will pass this on until justice is done."[157]

In 1969, Plan de Santa Bárbara was drafted as a 155-page document that outlined the foundation of Chicano Studies programs in higher education. It called for students, faculty, employees and the community to come together as "central and decisive designers and administrators of these programs".[158] Chicano students and activists asserted that universities should exist to serve the community.[130] However, by the mid-1970s, much of the radicalism of earlier Chicano studies became deflated by the education system, aimed to alter Chicano Studies programs from within.[159] Mario García argued that one "encountered a deradicalization of the radicals".[159] Some opportunistic faculty avoided their political responsibilities to the community. University administrators co-opted oppositional forces within Chicano Studies programs and encouraged tendencies that led "to the loss of autonomy of Chicano Studies programs."[159] At the same time, "a domesticated Chicano Studies provided the university with the facade of being tolerant, liberal, and progressive."[159]

Some Chicanos argued that the solution was to create "publishing outlets that would challenge Anglo control of academic print culture with its rules on peer review and thereby publish alternative research," arguing that a Chicano space in the colonial academy could "avoid colonization in higher education".[159] In an attempt to establish educational autonomy, they worked with institutions like the Ford Foundation, but found that "these organizations presented a paradox".[159] Rodolfo Acuña argued that such institutions "quickly became content to only acquire funding for research and thereby determine the success or failure of faculty".[159] Chicano Studies became "much closer [to] the mainstream than its practitioners wanted to acknowledge."[159] Others argued that Chicano Studies at UCLA shifted from its earlier interests in serving the Chicano community to gaining status within the colonial institution through a focus on academic publishing, which alienated it from the community.[159]

In 2012, the Mexican American Studies Department Programs (MAS) in Tucson Unified School District were banned after a campaign led by Anglo-American politician Tom Horne accused it of working to "promote the overthrow of the U.S. government, promote resentment toward a race or class of people, are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group or advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals."[160] Classes on Latino literature, American history/Mexican-American perspectives, Chicano art, and an American government/social justice education project course were banned. Readings of In Lak'ech from Luis Valdez's poem Pensamiento Serpentino were also banned.[160]

Seven books, including Paulo Friere's Pedagogy of the Oppressed and works covering Chicano history and critical race theory, were banned, taken from students, and stored away.[161] The ban was overturned in 2017 by Judge A. Wallace Tashima, who ruled that it was unconstitutional and motivated by racism by depriving Chicano students of knowledge, thereby violating their Fourteenth Amendment right.[162] The Xicanx Institute for Teaching & Organizing (XITO) emerged to carry on the legacy of the MAS programs.[163] Chicanos continue to support the institution of Chicano studies programs. In 2021, students at Southwestern College, the closest college to the Mexico-United States Border urged for the creation of a Chicanx Studies Program to service the predominately Latino student body.[164]

Rejection of borders

[edit]

The Chicano concept of sin fronteras rejects the idea of borders.[166] Some argued that the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transformed the Rio Grande region from a rich cultural center to a rigid border poorly enforced by the United States government.[167] At the end of the Mexican-American War, 80,000 Spanish-Mexican-Indian people were forced into sudden U.S. habitation.[167] Some Chicanos identified with the idea of Aztlán as a result, which celebrated a time preceding land division and rejected the "immigrant/foreigner" categorization by Anglo society.[168] Chicano activists have called for unionism between both Mexicans and Chicanos on both sides of the border.[169]

In the early 20th century, the border crossing had become a site of dehumanization for Mexicans.[165] Protests in 1910 arose along the Santa Fe Bridge from abuses committed against Mexican workers while crossing the border.[165] The 1917 Bath riots erupted after Mexicans crossing the border were required to strip naked and be disinfected with chemical agents like gasoline, kerosene, sulfuric acid, and Zyklon B, the latter of which was the fumigation of choice and would later notoriously be used in the gas chambers of Nazi Germany.[165] Chemical dousing continued into the 1950s.[165] During the early 20th century, Chicanos used corridos "to counter Anglocentric hegemony."[170] Ramón Saldivar stated that "corridos served the symbolic function of empirical events and for creating counterfactual worlds of lived experience (functioning as a substitute for fiction writing)."[170]

Newspaper Sin Fronteras (1976–1979) openly rejected the Mexico-United States border. The newspaper considered it "to be only an artificial creation that in time would be destroyed by the struggles of Mexicans on both sides of the border" and recognized that "Yankee political, economic, and cultural colonialism victimized all Mexicans, whether in the U.S. or in Mexico." Similarly, the General Brotherhood of Workers (CASA), important to the development of young Chicano intellectuals and activists, identified that, as "victims of oppression, Mexicanos could achieve liberation and self-determination only by engaging in a borderless struggle to defeat American international capitalism."[171]

Chicana theorist Gloria E. Anzaldúa notably emphasized the border as a "1,950 mile-long wound that does not heal". In referring to the border as a wound, writer Catherine Leen suggests that Anzaldúa recognizes "the trauma and indeed physical violence very often associated with crossing the border from Mexico to the US, but also underlies the fact that the cyclical nature of this immigration means that this process will continue and find little resolution."[172][173] Anzaldúa writes that la frontera signals "the coming together of two self-consistent but habitually incompatible frames of reference [which] cause un choque, a cultural collision" because "the U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds."[174] Chicano and Mexican artists and filmmakers continue to address "the contentious issues of exploitation, exclusion, and conflict at the border and attempt to overturn border stereotypes" through their work.[172] Luis Alberto Urrea writes "the border runs down the middle of me. I have a barbed wire fence neatly bisecting my heart."[173]

Sociological aspects

[edit]Criminalization

[edit]

The 19th-century and early-20th-century image of the Mexican in the U.S. was "that of the greasy Mexican bandit or bandito," who was perceived as criminal because of Mestizo ancestry and "Indian blood."[176] This rhetoric fueled anti-Mexican sentiment among whites, which led to many lynchings of Mexicans in the period as an act of racist violence.[176] One of the largest massacres of Mexicans was known as La Matanza in Texas, where hundreds of Mexicans were lynched by white mobs.[177] Many whites viewed Mexicans as inherently criminal, which they connected to their Indigenous ancestry.[176] White historian Walter P. Webb wrote in 1935, "there is a cruel streak in the Mexican nature ... this cruelty may be a heritage from the Spanish and of the Inquisition; it may, and doubtless should be, attributed partly to Indian blood."[176]

The "greasy bandito" stereotype of the old West evolved into images of "crazed Zoot-Suiters and pachuco killers in the 1940s, to contemporary cholos, gangsters, and gang members."[176] Pachucos were portrayed as violent criminals in American mainstream media, which fueled the Zoot Suit Riots; initiated by off-duty policemen conducting a vigilante-hunt, the riots targeted Chicano youth who wore the zoot suit as a symbol of empowerment.[178] On-duty police supported the violence against Chicano zoot suiters; they "escorted the servicemen to safety and arrested their Chicano victims."[178] Arrest rates of Chicano youth rose during these decades, fueled by the "criminal" image portrayed in the media, by politicians, and by the police.[178] Not aspiring to assimilate in Anglo-American society, Chicano youth were criminalized for their defiance to cultural assimilation: "When many of the same youth began wearing what the larger society considered outlandish clothing, sporting distinctive hairstyles, speaking in their own language (Caló), and dripping with attitude, law enforcement redoubled their efforts to rid [them from] the streets."[179]

In the 1970s and subsequent decades, there was a wave of police killings of Chicanos. One of the most prominent cases was Luis "Tato" Rivera, who was a 20-year-old Chicano shot in the back by officer Craig Short in 1975. 2,000 Chicano demonstrators showed up to the city hall of National City, California in protest. Short was indicted for manslaughter by district attorney Ed Miller and was acquitted of all charges. Short was later appointed acting chief of police of National City in 2003.[176] Another high-profile case was the murder of Ricardo Falcón, a student at the University of Colorado and leader of the United Latin American Students (UMAS), by Perry Brunson, a member of the far-right American Independent Party, at a gas station. Bruson was tried for manslaughter and was "acquitted by an all-White jury".[176] Falcón became a martyr for the Chicano Movement as police violence increased in the subsequent decades.[176] Similar cases led sociologist Alfredo Mirandé to refer to the U.S. criminal justice system as gringo justice, because "it reflected one standard for Anglos and another for Chicanos."[180]

The criminalization of Chicano youth in the barrio remains omnipresent. Chicano youth who adopt a cholo or chola identity endure hyper-criminalization in what has been described by Victor Rios as the youth control complex.[182] While older residents initially "embraced the idea of a chola or cholo as a larger subculture not necessarily associated with crime and violence (but rather with a youthful temporary identity), law enforcement agents, ignorant or disdainful of barrio life, labeled youth who wore clean white tennis shoes, shaved their heads, or long socks, as deviant."[181] Community members were convinced by the police of cholo criminality, which led to criminalization and surveillance "reminiscent of the criminalization of Chicana and Chicano youth during the Zoot-Suit era in the 1940s."[181]

Sociologist José S. Plascencia-Castillo refers to the barrio as a panopticon that leads to intense self-regulation, as Cholo youth are both scrutinized by law enforcement to "stay in their side of town" and by the community who in some cases "call the police to have the youngsters removed from the premises".[181] The intense governance of Chicano youth, especially of cholo identity, has deep implications on youth experience, affecting their physical and mental health as well as their outlook on the future. Some youth feel they "can either comply with the demands of authority figures, and become obedient and compliant, and suffer the accompanying loss of identity and self-esteem, or, adopt a resistant stance and contest social invisibility to command respect in the public sphere."[181]

Gender and sexuality

[edit]Chicanas

[edit]

Chicanas often confront objectification in Anglo society, being perceived as "exotic", "lascivious", and "hot" at a very young age while also facing denigration as "barefoot", "pregnant", "dark", and "low-class".[183] These perceptions in society create numerous negative sociological and psychological effects, such as excessive dieting and eating disorders. Social media may enhance these stereotypes of Chicana women and girls.[183] Numerous studies have found that Chicanas experience elevated levels of stress as a result of sexual expectations by society, as well as their parents and families.[184]

Although many Chicana youth desire open conversation of these gender roles and sexuality, as well as mental health, these issues are often not discussed openly in Chicano families, which perpetuates unsafe and destructive practices.[184] While young Chicanas are objectified, middle-aged Chicanas discuss feelings of being invisible, saying they feel trapped in balancing family obligations to their parents and children while attempting to create a space for their own sexual desires.[184] The expectation that Chicanas should be "protected" by Chicanos may also constrict the agency and mobility of Chicanas.[184]

Chicanas are often relegated to a secondary and subordinate status in families.[185] Cherrie Moraga argues that this issue of patriarchal ideology in Chicano and Latino communities runs deep, as the great majority of Chicano and Latino men believe in and uphold male supremacy.[185] Moraga argues that this ideology is not only upheld by men in Chicano families, but also by mothers in their relationship to their children: "the daughter must constantly earn the mother's love, prove her fidelity to her. The son—he gets her love for free."[185]

Chicanos

[edit]Chicanos develop their manhood within a context of marginalization in white society.[186] Some argue that "Mexican men and their Chicano brothers suffer from an inferiority complex due to the conquest and genocide inflicted upon their Indigenous ancestors," which leaves Chicano men feeling trapped between identifying with the so-called "superior" European and the so-called "inferior" Indigenous sense of self.[186] This conflict may manifest itself in the form of hypermasculinity or machismo, in which a "quest for power and control over others in order to feel better" about oneself is undertaken.[186] This may result in men developing abusive behaviors, the development of an impenetrable "cold" persona, alcohol abuse, and other destructive and self-isolating behaviors.[186]

The lack of discussion of what it means to be a Chicano man between Chicano male youth and their fathers or their mothers creates a search for identity that often leads to self-destructive behaviors.[187] Chicano male youth tend to learn about sex from their peers as well as older male family members who perpetuate the idea that as men they have "a right to engage in sexual activity without commitment".[187] The looming threat of being labeled a joto (gay) for not engaging in sexual activity also conditions many Chicanos to "use" women for their own sexual desires.[187] Gabriel S. Estrada argues that the criminalization of Chicanos proliferates further homophobia among Chicano boys and men who may adopt hypermasculine personas to escape such association.[188]

Heteronormativity

[edit]Heteronormative gender roles are typically enforced in Chicano families.[185] Any deviation from gender and sexual conformity, such as effeminacy in Chicanos or lesbianism in Chicanas, is commonly perceived as a weakening or attack of la familia.[185] However, Chicano men who retain a masculine or machismo performance are afforded some mobility to discreetly engage in homosexual behaviors, as long as it remains on the fringes.[185]

Queer Chicana/os may seek refuge in their families, if possible, because it is difficult for them to find spaces where they feel safe in the dominant and hostile white gay culture.[189] Chicano machismo, religious traditionalism, and homophobia creates challenges for them to feel accepted by their families.[189] Gabriel S. Estrada argues that upholding "Judeo-Christian mandates against homosexuality that are not native to [Indigenous Mexico]," exiles queer Chicana/o youth.[188]

Mental health

[edit]

Chicanos may seek out both Western biomedical healthcare and Indigenous health practices when dealing with trauma or illness. The effects of colonization are proven to produce psychological distress among Indigenous communities. Intergenerational trauma, along with racism and institutionalized systems of oppression, have been shown to adversely impact the mental health of Chicanos and Latinos. Mexican Americans are three times more likely than European Americans to live in poverty.[190] Chicano adolescent youth experience high rates of depression and anxiety. Chicana adolescents have higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation than their European-American and African-American peers. Chicano adolescents experience high rates of homicide, and suicide. Chicanos ages ten to seventeen are at a greater risk for mood and anxiety disorders than their European-American and African-American peers. Scholars have determined that the reasons for this are unclear due to the scarcity of studies on Chicano youth, but that intergenerational trauma, acculturative stress, and family factors are believed to contribute.[191]

Among Mexican immigrants who have lived in the United States for less than thirteen years, lower rates of mental health disorders were found in comparison to Mexican-Americans and Chicanos born in the United States. Scholar Yvette G. Flores concludes that these studies demonstrate that "factors associated with living in the United States are related to an increased risk of mental disorders." Risk factors for negative mental health include historical and contemporary trauma stemming from colonization, marginalization, discrimination, and devaluation. The disconnection of Chicanos from their Indigeneity has been cited as a cause of trauma and negative mental health:[190]

Loss of language, cultural rituals, and spiritual practices creates shame and despair. The loss of culture and language often goes unmourned, because it is silenced and denied by those who occupy, conquer, or dominate. Such losses and their psychological and spiritual impact are passed down across generations, resulting in depression, disconnection, and spiritual distress in subsequent generations, which are manifestations of historical or intergenerational trauma.[192]

Psychological distress may emerge from Chicanos being "othered" in society since childhood and is linked to psychiatric disorders and symptoms which are culturally bound—susto (fright), nervios (nerves), mal de ojo (evil eye), and ataque de nervios (an attack of nerves resembling a panic attack).[192] Manuel X. Zamarripa discusses how mental health and spirituality are often seen as disconnected subjects in Western perspectives. Zamarripa states "in our community, spirituality is key for many of us in our overall wellbeing and in restoring and giving balance to our lives". For Chicanos, Zamarripa recognizes that identity, community, and spirituality are three core aspects which are essential to maintaining good mental health.[193]

Spirituality

[edit]

Chicano spirituality has been described as a process of engaging in a journey to unite one's consciousness for the purposes of cultural unity and social justice. It brings together many elements and is therefore hybrid in nature. Scholar Regina M Marchi states that Chicano spirituality "emphasizes elements of struggle, process, and politics, with the goal of creating a unity of consciousness to aid social development and political action".[195] Lara Medina and Martha R. Gonzales explain that "reclaiming and reconstructing our spirituality based on non-Western epistemologies is central to our process of decolonization, particularly in these most troubling times of incessant Eurocentric, heteronormative patriarchy, misogyny, racial injustice, global capitalist greed, and disastrous global climate change."[196] As a result, some scholars state that Chicano spirituality must involve a study of Indigenous Ways of Knowing (IWOK).[197] The Circulo de Hombres group in San Diego, California spiritually heals Chicano, Latino, and Indigenous men "by exposing them to Indigenous-based frameworks, men of this cultural group heal and rehumanize themselves through Maya-Nahua Indigenous-based concepts and teachings", helping them process intergenerational trauma and dehumanization that has resulted from colonization. A study on the group reported that reconnecting with Indigenous worldviews was overwhelmingly successful in helping Chicano, Latino, and Indigenous men heal.[198][199] As stated by Jesus Mendoza, "our bodies remember our indigenous roots and demand that we open our mind, hearts, and souls to our reality".[200]

Chicano spirituality is a way for Chicanos to listen, reclaim, and survive while disrupting coloniality. While historically Catholicism was the primary way for Chicanos to express their spirituality, this is changing rapidly. According to a Pew Research Center report in 2015, "the primary role of Catholicism as a conduit to spirituality has declined and some Chicanos have changed their affiliation to other Christian religions and many more have stopped attending church altogether." Increasingly, Chicanos are considering themselves spiritual rather than religious or part of an organized religion. A study on spirituality and Chicano men in 2020 found that many Chicanos indicated the benefits of spirituality through connecting with Indigenous spiritual beliefs and worldviews instead of Christian or Catholic organized religion in their lives.[198] Dr. Lara Medina defines spirituality as (1) Knowledge of oneself—one's gifts and one's challenges, (2) Co-creation or a relationship with communities (others), and (3) A relationship with sacred sources of life and death 'the Great Mystery' or Creator. Jesus Mendoza writes that, for Chicanos, "spirituality is our connection to the earth, our pre-Hispanic history, our ancestors, the mixture of pre-Hispanic religion with Christianity ... a return to a non-Western worldview that understands all life as sacred."[200] In her writing on Gloria Anzaldua's idea of spiritual activism, AnaLouise Keating states that spirituality is distinct from organized religion and New Age thinking. Leela Fernandes defines spirituality as follows:

When I speak of spirituality, at the most basic level I am referring to an understanding of the self as encompassing body and mind, as well as spirit. I am also referring to a transcendent sense of interconnection that moves beyond the knowable, visible material world. This sense of interconnection has been described variously as divinity, the sacred, spirit, or simply the universe. My understanding is also grounded in a form of lived spirituality, which is directly accessible to all and which does not need to be mediated by religious experts, institutions or theological texts; this is what is often referred to as the mystical side of spirituality... Spirituality can be as much about practices of compassion, love, ethics, and truth defined in nonreligious terms as it can be related to the mystical reinterpretations of existing religious traditions.[201]