Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

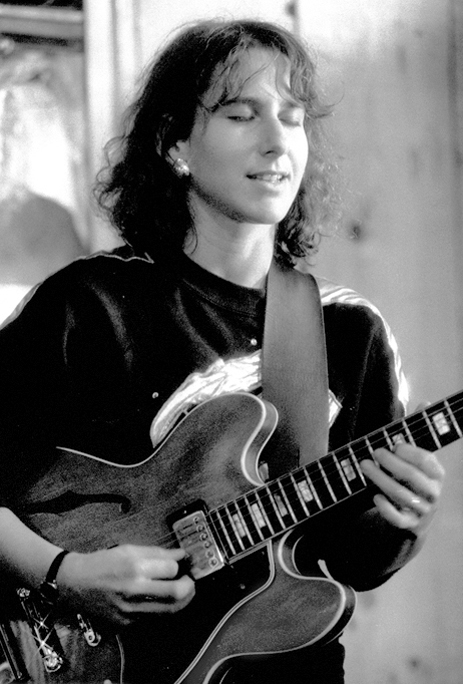

Emily Remler

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Emily Remler (September 18, 1957 – May 4, 1990)[1] was an American jazz guitarist, active from the late 1970s until her death in 1990.

Early life and influences

[edit]Born in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey,[2] Remler began playing guitar at age ten. She listened to pop and rock guitarists like Jimi Hendrix and Johnny Winter. At the Berklee College of Music in the 1970s, she listened to jazz guitarists Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery, Herb Ellis, Pat Martino, and Joe Pass.

Career

[edit]Remler settled in New Orleans, where she played in blues and jazz clubs, working with bands such as Four Play and Little Queenie and the Percolators[3] before beginning her recording career in 1981. She was praised by jazz guitarist Herb Ellis, who referred to her as "the new superstar of guitar" and introduced her at the Concord Jazz Festival in 1978.

In a 1982 interview with People magazine, she said: "I may look like a nice Jewish girl from New Jersey, but inside I'm a 50-year-old, heavy-set black man with a big thumb, like Wes Montgomery."

Her first album as a band leader, Firefly, gained positive reviews,[3] as did Take Two and Catwalk. She recorded Together with guitarist Larry Coryell. She participated in the Los Angeles version of Sophisticated Ladies from 1981 to 1982 and toured for several years with Astrud Gilberto. She also made two guitar instruction videos.

In 1985, she won Guitarist of the Year in Down Beat magazine's international poll, and performed in that year's guitar festival at Carnegie Hall.[4] In 1988, she was artist in residence at Duquesne University and the next year received the Distinguished Alumni award from Berklee. Bob Moses, the drummer on Transitions and Catwalk, said, "Emily had that loose, relaxed feel. She swung harder and simpler. She didn't have to let you know that she was a virtuoso in the first five seconds."[5]

Remler married Jamaican jazz pianist Monty Alexander in 1981; the marriage ended in 1984. Thereafter, she had a brief relationship with Coryell following her first divorce.[6]

Her first guitar was her brother's Gibson ES-330. She played a Borys[7] B120 hollow-body electric towards the end of the 1980s. Her acoustic guitars included a 1984 Collectors Series Ovation and a nylon-string Korocusci classical guitar that she used for bossa nova.

When asked how she wanted to be remembered she remarked, "Good compositions, memorable guitar playing and my contributions as a woman in music...but the music is everything, and it has nothing to do with politics or the women's liberation movement."[8]

Death

[edit]Remler bore the scars of her longstanding opioid use disorder,[5] which is believed to have contributed to her death.[9][5] In May, 1990, she died of heart failure at the age of 32 while on tour in Australia.[2]

Remler is buried in Block 4, Row 2, Grave 18 (Section 2, Field of Ephron) at New Montefiore Cemetery, New York.[10]

Tributes

[edit]The album Just Friends: A Gathering in Tribute to Emily Remler, Volume 1 (Justice Records JR 0502-2) was released in 1990, and Volume 2 (JR 0503-2) followed in 1991. Performers from these two albums included guitarists Herb Ellis, Leni Stern, Marty Ashby, and Steve Masakowski; bassists Eddie Gómez, Lincoln Goines, and Steve Bailey; drummer Marvin "Smitty" Smith; pianists Bill O'Connell and David Benoit; and saxophonist Nelson Rangell, among others.

David Benoit wrote the song "6-String Poet", from his album Inner Motion (GRP, 1990), as a tribute to Remler.[11]

The 1995 book Madame Jazz: Contemporary Women Instrumentalists by Leslie Gourse includes a posthumous chapter on Remler, based on interviews conducted while she was alive.[12]

In 2002, West Coast guitarist Skip Heller recorded with his quartet a song called "Emily Remler" in her memory,[13] released as track No. 5 on his record Homegoing (Innova Recordings).

Jazz guitarist Sheryl Bailey's 2010 album A New Promise was a tribute to Emily Remler. Aged 18, Bailey first saw Remler perform, at the University of Pittsburgh Jazz Festival in 1984 - she was inspired to take her own guitar studies. Bailey said "She paved the way for me. ... I really wanted to hear Emily's person in me when I played. It meant a lot to me to do this tribute and pay homage to her and to say thank you."[14] On the album, Bailey collaborated with Pittsburgh's Three Rivers Jazz Orchestra and producer Marty Ashby on eight tracks, including three composed by Remler ("East to Wes", "Mocha Spice", and "Carenia").

Discography

[edit]As leader/co-leader

[edit]| Year released | Title | Label | Personnel/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Firefly | Concord | With Hank Jones (piano), Bob Maize (bass) and Jake Hanna (drums) |

| 1982 | Take Two | Concord | With James Williams (piano), Don Thomson (bass) and Terry Clarke (drums). |

| 1983 | Transitions | Concord | With John D'earth (trumpet), Eddie Gomez (bass) and Bob Moses (drums). |

| 1985 | Catwalk | Concord | With John D'earth (trumpet), Eddie Gomez (bass) and Bob Moses (percussion). |

| 1985 | Together | Concord | With Larry Coryell. |

| 1988 | East to Wes | Concord | With Hank Jones (piano), Buster Williams (bass) and Marvin "Smitty" Smith (drums). |

| 1990 | This Is Me | Justice | With David Benoit (keyboards), Jimmy Johnson and Lincoln Goines (bass), Luis Conte, Edson Aparecido da Silva "Café" and Jeffrey Weber (percussion), Jay Ashby (percussion and trombone), Jeff Porcaro, Ricky Sebastian and Duduka Da Fonseca (drums), Romero Lubambo (acoustic guitar), Maúcha Adnet (vocals). |

| 2024 | Cookin' at the Queens: Live in Las Vegas 1984 & 1988 | Resonance | With Cocho Arbe (piano), Carson Smith (bass), Tom Montgomery and John Pisci (drums). |

As guest

[edit]| Year recorded |

Leader | Title | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | The Clayton Brothers | It's All In The Family | Concord |

| 1985 | Ray Brown | Soular Energy | Concord |

| 1986 | John Colianni | John Colianni | Concord |

| 1986 | Rosemary Clooney | Rosemary Clooney Sings the Music of Jimmy Van Heusen | Concord |

| 1989 | David Benoit | Waiting for Spring | GRP |

| 1989 | Susannah McCorkle | No More Blues | Concord |

| 1990 | Susannah McCorkle | Sabia | Concord |

| 1990 | Richie Cole | Bossa International | Milestone |

Videos

[edit]- 1990: Bebop and Swing Guitar (VHS, reissued on DVD in 2008)

- 1990: Advanced Jazz and Latin Improvisation (VHS, reissued on DVD in 2008)

- 2005: Sal Salvador, Joe Pass, Mundell Lowe, Charlie Byrd, Emily Remler, Tal Farlow – Learn Jazz Guitar Chords With 6 Great Masters! (DVD, DVD-Video)

- 2005: Emily Remler, Joe Pass, Tuck Andress, Brian Setzer, Joe Beck, Duke Robillard – Learn Jazz Guitar With 6 Great Masters! (DVD, DVD-Video)

References

[edit]- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. pp. 332–333. ISBN 0-85112-580-8.

- ^ a b "Emily Remler Dies On Australia Tour; Guitarist Was 32". The New York Times. May 8, 1990. Retrieved February 25, 2025.

- ^ a b Uhl, Don (December 11, 1981). "Remler plays good guitar, and not because she's a girl". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. p. 6D. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, John S. (May 15, 1985). "Concert: Guitar Festival". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Gluckin, Tzvi (July 29, 2014). "Forgotten Heroes: Emily Remler". Premier Guitar. Retrieved February 25, 2025.

- ^ West, Michael J. "The Rise and Decline of Guitarist Emily Remler". Jazztimes.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Jazz Solid". Borysguitars.com. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Reddan, James; Herzig, Monika; Kahr, Michael, eds. (2022). The Routledge Companion to Jazz and Gender. New York: Routledge. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-00-308187-6.

- ^ Scott Yanow. "Emily Remler | Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ "New Montefiore Cemetery - Queens, NY". Newmontefiorecemetery.org. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "David Benoit Biography". Oldies.com. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Gourse, Leslie (1995). Madame Jazz: Contemporary Women Instrumentalists. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 1-4237-4126-9. OCLC 62338157.

- ^ Skip Heller Quartet: Homegoing, by C. Michael Bailey Archived August 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Allaboutjazz.com, November 25, 2002. Retrieved 17 August 2019 ]

- ^ Guitarist Sheryl Bailey's "A New Promise" CD to Be Released February 2 by MCG Jazz. January 8, 2010. By Terry Hinte Archived October 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Prweb.com. Retrieved 31 December 2019.]

External links

[edit]- Emily Remler discography at Discogs

- Emily Remler at Find a Grave

- Emily Remler (in Dutch)

- Emily Remler Guitar Tabs

- Emily Remler: a musical remembrance