Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Middle-earth

View on Wikipedia

| Middle-earth | |

|---|---|

| The Lord of the Rings location | |

| |

| Created by | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Central continent of fantasy world; also used as a short-hand for the whole legendarium |

Middle-earth is the setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the oecumene (i.e. the human-inhabited world, or the central continent of Earth) in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

Middle-earth is the main continent of Earth (Arda) in an imaginary period of the past, ending with Tolkien's Third Age, about 6,000 years ago.[T 1] Tolkien's tales of Middle-earth mostly focus on the north-west of the continent. This region is suggestive of Europe, the north-west of the Old World, with the environs of the Shire reminiscent of England, but, more specifically, the West Midlands, with the town at its centre, Hobbiton, at the same latitude as Oxford.

Tolkien's Middle-earth is peopled not only by Men, but by Elves, Dwarves, Ents, and Hobbits, and by monsters including Dragons, Trolls, and Orcs. Through the imagined history, the peoples other than Men dwindle, leave or fade, until, after the period described in the books, only Men are left on the planet.

Context: Tolkien's legendarium

[edit]

Tolkien's stories chronicle the struggle to control the world (called Arda) and the continent of Middle-earth between, on one side, the angelic Valar, the Elves and their allies among Men; and, on the other, the demonic Melkor or Morgoth (a Vala fallen into evil), his followers, and their subjects, mostly Orcs, Dragons and enslaved Men.[T 2] In later ages, after Morgoth's defeat and expulsion from Arda, his place is taken by his lieutenant Sauron, a Maia.[T 3]

The Valar withdrew from direct involvement in the affairs of Middle-earth after the defeat of Morgoth, but in later years they sent the wizards or Istari to help in the struggle against Sauron. The most important wizards were Gandalf the Grey and Saruman the White. Gandalf remained true to his mission and proved crucial in the fight against Sauron. Saruman, however, became corrupted and sought to establish himself as a rival to Sauron for absolute power in Middle-earth. Other races involved in the struggle against evil were Dwarves, Ents and most famously Hobbits. The early stages of the conflict are chronicled in The Silmarillion, while the final stages of the struggle to defeat Sauron are told in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.[T 3]

Conflict over the possession and control of precious or magical objects is a recurring theme in the stories. The First Age is dominated by the doomed quest of the elf Fëanor and most of his Noldorin clan to recover three precious jewels called the Silmarils that Morgoth stole from them (hence the title The Silmarillion). The Second and Third Age are dominated by the forging of the Rings of Power, and the fate of the One Ring forged by Sauron, which gives its wearer the power to control or influence those wearing the other Rings of Power.[T 3]

Etymology

[edit]

In ancient Germanic mythology, the world of Men is known by several names. The Old English middangeard descends from an earlier Germanic word and so has cognates such as the Old Norse Miðgarðr from Norse mythology, transliterated to modern English as Midgard. The original meaning of the second element, from proto-Germanic gardaz, was "enclosure", cognate with English "yard"; middangeard was assimilated by folk etymology to "middle earth".[T 4][2] Middle-earth was at the centre of nine worlds in Norse mythology, and of three worlds (with heaven above, hell below) in some later Christian versions.[1]

Use by Tolkien

[edit]Tolkien's first encounter with the term middangeard, as he stated in a letter, was in an Old English fragment he studied in 1913–1914:[T 5]

Éala éarendel engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum sended.

Hail Earendel, brightest of angels / above the middle-earth sent unto men.

This is from the Crist 1 poem by Cynewulf. The name Éarendel was the inspiration for Tolkien's mariner Eärendil,[T 5] who set sail from the lands of Middle-earth to ask for aid from the angelic powers, the Valar. Tolkien's earliest poem about Eärendil, from 1914, the same year he read the Crist poem, refers to "the mid-world's rim".[3] Tolkien considered middangeard to be "the abiding place of men",[T 6] the physical world in which Man lives out his life and destiny, as opposed to the unseen worlds above and below it, namely Heaven and Hell. He states that it is "my own mother-earth for place", but in an imaginary past time, not some other planet.[T 7] He began to use the term "Middle-earth" in the late 1930s, in place of the earlier terms "Great Lands", "Outer Lands", and "Hither Lands".[3] The first published appearance of the word "Middle-earth" in Tolkien's works is in the prologue to The Lord of the Rings: "Hobbits had, in fact, lived quietly in Middle-earth for many long years before other folk even became aware of them".[T 8]

Extended usage

[edit]

The term Middle-earth has come to be applied as a short-hand for the entirety of Tolkien's legendarium, instead of the technically more appropriate, but lesser known terms "Arda" for the physical world and "Eä" for the physical reality of creation as a whole. In careful geographical terms, Middle-earth is a continent on Arda, excluding regions such as Aman and the isle of Númenor. The alternative wider use is reflected in book titles such as The Complete Guide to Middle-earth, The Road to Middle-earth, The Atlas of Middle-earth, and Christopher Tolkien's 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth.[4][5]

In other works

[edit]Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter states that Tolkien's Middle-earth is the known world, "recalling the Norse Midgard and the equivalent words in early English", noting that Tolkien made it clear that this was "our world ... in a purely imaginary ... period of antiquity".[6] Tolkien explained in a letter to his publisher that it "is just a use of Middle English middle-erde (or erthe), altered from Old English Middangeard: the name for the inhabited lands of men 'between the seas'."[T 4] There are allusions to a similarly- or identically-named world in the work of other writers both before and after him. William Morris's 1870 translation of the Volsung Saga calls the world "Midgard".[7] Margaret Widdemer's 1918 poem "The Gray Magician" contains the lines: "I was living very merrily on Middle Earth / As merry as a maid may be / Till the Gray Magician came down along the road / And flung his cobweb cloak on me..."[8] C. S. Lewis's 1938–1945 Space Trilogy calls the home planet "Middle-earth" and specifically references Tolkien's unpublished legendarium; both men were members of the Inklings literary discussion group.[9]

Geography

[edit]Within the overall context of his legendarium, Tolkien's Middle-earth was part of his created world of Arda (which includes the Undying Lands of Aman and Eressëa, removed from the rest of the physical world), which itself was part of the wider creation he called Eä. Aman and Middle-earth are separated from each other by the Great Sea Belegaer, though they make contact in the far north at the Grinding Ice or Helcaraxë. The western continent, Aman, was the home of the Valar, and the Elves called the Eldar.[T 9] On the eastern side of Middle-earth was the Eastern Sea. Most of the events in Tolkien's stories take place in the north-west of Middle-earth. In the First Age, further to the north-west was the subcontinent Beleriand; it was engulfed by the ocean at the end of the First Age.[5]

Maps

[edit]

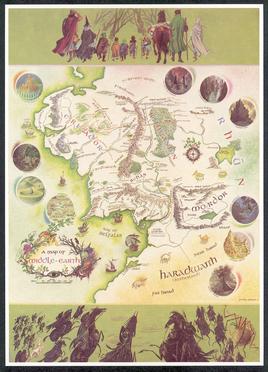

Tolkien prepared several maps of Middle-earth. Some were published in his lifetime. The main maps are those published in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and Unfinished Tales, and appear as foldouts or illustrations. Tolkien insisted that maps be included in the book for the benefit of readers, despite the expense involved.[T 10] The definitive and iconic map of Middle-earth was published in The Lord of the Rings.[T 11] It was refined with Tolkien's approval by the illustrator Pauline Baynes, using Tolkien's detailed annotations, with vignette images and larger paintings at top and bottom, into a stand-alone poster, "A Map of Middle-earth".[10]

Cosmology

[edit]

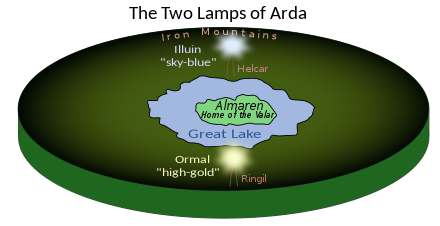

In Tolkien's conception, Arda was created specifically as "the Habitation" (Imbar or Ambar) for the Children of Ilúvatar (Elves and Men).[12] It is envisaged in a flat Earth cosmology, with the stars, and later also the sun and moon, revolving around it. Tolkien's sketches show a disc-like face for the world which looked up to the stars. However, Tolkien's legendarium addresses the spherical Earth paradigm by depicting a catastrophic transition from a flat to a spherical world, known as the Akallabêth, in which Aman became inaccessible to mortal Men.[11]

Correspondence with the geography of Earth

[edit]Tolkien described the region in which the Hobbits lived as "the North-West of the Old World, east of the Sea",[T 8] and the north-west of the Old World is essentially Europe, especially Britain. However, as he noted in private letters, the geographies do not match, and he did not consciously make them match when he was writing:[T 12]

As for the shape of the world of the Third Age, I am afraid that was devised 'dramatically' rather than geologically, or paleontologically.[T 12]

I am historically minded. Middle-earth is not an imaginary world. ... The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary. The essentials of that abiding place are all there (at any rate for inhabitants of N.W. Europe), so naturally it feels familiar, even if a little glorified by enchantment of distance in time.[T 13]

...if it were 'history', it would be difficult to fit the lands and events (or 'cultures') into such evidence as we possess, archaeological or geological, concerning the nearer or remoter part of what is now called Europe; though the Shire, for instance, is expressly stated to have been in this region...I hope the, evidently long but undefined gap in time between the Fall of Barad-dûr and our Days is sufficient for 'literary credibility', even for readers acquainted with what is known as 'pre-history'. I have, I suppose, constructed an imaginary time, but kept my feet on my own mother-earth for place. I prefer that to the contemporary mode of seeking remote globes in 'space'.[T 7]

In another letter, Tolkien made correspondences in latitude between Europe and Middle-earth:

The action of the story takes place in the North-west of 'Middle-earth', equivalent in latitude to the coastlands of Europe and the north shores of the Mediterranean. ... If Hobbiton and Rivendell are taken (as intended) to be at about the latitude of Oxford, then Minas Tirith, 600 miles south, is at about the latitude of Florence. The Mouths of Anduin and the ancient city of Pelargir are at about the latitude of ancient Troy.[T 14]

In another letter he stated:

...Thank you very much for your letter. ... It came while I was away, in Gondor (sc. Venice), as a change from the North Kingdom, or I would have answered before.[13]

He did confirm, however, that the Shire, the land of his Hobbit heroes, was based on England, in particular the West Midlands of his childhood.[T 15] In the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien writes: "Those days, the Third Age of Middle-earth, are now long past, and the shape of all lands has been changed..."[T 16] The Appendices make several references in both history and etymology of topics "now" (in modern English languages) and "then" (ancient languages);

The year no doubt was of the same length,¹ [the footnote here reads: 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 46 seconds.] for long ago as those times are now reckoned in years and lives of men, they were not very remote according to the memory of the Earth.[T 17]

Both the Appendices and The Silmarillion mention constellations, stars and planets that correspond to those seen in the northern hemisphere of Earth, including the Sun, the Moon, Orion (and his belt),[T 18] Ursa Major[T 19][T 20] and Mars. A map annotated by Tolkien places Hobbiton on the same latitude as Oxford, and Minas Tirith at the latitude of Ravenna, Italy. He used Belgrade, Cyprus, and Jerusalem as further reference points.[14]

History

[edit]

The history of Middle-earth, as described in The Silmarillion, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe.[T 21] Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees and the Years of the Sun.[T 22] A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees (by which time the Ainur had already long inhabited Arda) and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun.[T 23]

Arda is, as critics have noted, "our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in the past."[15] As such, it has not only an immediate story but a history, and the whole thing is an "imagined prehistory" of the Earth as it is now.[17]

Peoples and their languages

[edit]Ainur

[edit]The Ainur were angelic beings created by the one god of Eä, Eru Ilúvatar. The cosmological myth called the Ainulindalë, or "Music of the Ainur", describes how the Ainur sang for Ilúvatar, who then created Eä to give material form to their music. Many of the Ainur entered Eä, and the greatest of these were called the Valar. Melkor, the chief agent of evil in Eä, and later called Morgoth, was initially one of the Valar. With the Valar came lesser spirits of the Ainur, called the Maiar. Melian, the wife of the Elven King Thingol in the First Age, was a Maia. There were also evil Maiar, including the Balrogs and the second Dark Lord, Sauron. Sauron devised the Black Speech (Burzum) for his slaves (such as Orcs) to speak. In the Third Age, five of the Maiar were embodied and sent to Middle-earth to help the free peoples to overthrow Sauron. These are the Istari or Wizards, including Gandalf, Saruman, and Radagast.[T 24]

Elves

[edit]The Elves are known as "the Firstborn" of Ilúvatar: intelligent beings created by Ilúvatar alone, with many different clans. Originally Elves all spoke the same Common Eldarin ancestral tongue, but over thousands of years it diverged into different languages. The two main Elven languages were Quenya, spoken by the Light Elves, and Sindarin, spoken by the Dark Elves. Physically the Elves resemble humans; indeed, they can marry and have children with them, as shown by the few Half-elven in the legendarium. The Elves are agile and quick footed, being able to walk a tightrope unaided. Their eyesight is keen. Elves are immortal, unless killed in battle. They are re-embodied in Valinor if killed.[18][19]

Men

[edit]Men were "the Secondborn" of the Children of Ilúvatar: they awoke in Middle-earth much later than the Elves. Men (and Hobbits) were the last humanoid race to appear in Middle-earth: Dwarves, Ents and Orcs also preceded them. The capitalized term "Man" (plural "Men") is used as a gender-neutral racial description, to distinguish humans from the other human-like races of Middle-earth. In appearance they are much like Elves, but on average less beautiful. Unlike Elves, Men are mortal, ageing and dying quickly, usually living 40–80 years. However the Númenóreans could live several centuries, and their descendants the Dúnedain also tended to live longer than regular humans. This tendency was weakened both by time and by intermingling with lesser peoples.[20]

Dwarves

[edit]The Dwarves are a race of humanoids who are shorter than Men but larger than Hobbits. The Dwarves were created by the Vala Aulë, before the Firstborn awoke due to his impatience for the arrival of the children of Ilúvatar to teach and to cherish. When confronted and shamed for his presumption by Ilúvatar, Eru took pity on Aulë and gave his creation the gift of life but under the condition that they be taken and put to sleep in widely separated locations in Middle-earth and not to awaken until after the Firstborn were upon the Earth. They are mortal like Men, but live much longer, usually several hundred years. A peculiarity of Dwarves is that both males and females are bearded, and thus appear identical to outsiders. The language spoken by Dwarves is called Khuzdul, and was kept largely as a secret language for their own use. Like Hobbits, Dwarves live exclusively in Middle-earth. They generally reside under mountains, where they are specialists in mining and metalwork.[21]

Hobbits

[edit]Tolkien identified Hobbits as an offshoot of the race of Men. Another name for Hobbit is 'Halfling', as they were generally only half the size of Men. In their lifestyle and habits they closely resemble Men, and in particular Englishmen, except for their preference for living in holes underground. By the time of The Hobbit, most of them lived in the Shire, a region of the northwest of Middle-earth, having migrated there from further east.[22]

Other humanoid peoples

[edit]The Ents were treelike shepherds of trees, their name coming from an Old English word for giant.[23] Orcs and Trolls (made of stone) were evil creatures bred by Morgoth. They were not original creations but rather "mockeries" of the Children of Ilúvatar (Elves) and Ents, respectively, since only Ilúvatar has the ability to give conscious life to things. The precise origins of Orcs and Trolls are unclear, as Tolkien considered various possibilities and sometimes changed his mind, leaving several inconsistent accounts.[24] Late in the Third Age, the Uruks or Uruk-hai appeared: a race of Orcs of great size and strength that tolerate sunlight better than ordinary Orcs.[T 25] Tolkien also mentions "Men-orcs" and "Orc-men"; or "half-orcs" or "goblin-men". They share some characteristics with Orcs (like "slanty eyes") but look more like men.[T 26] Tolkien, a Catholic, realised he had created a dilemma for himself, as, if these beings were sentient and had a sense of right and wrong, then they must have souls and could not have been created wholly evil.[25][26]

Dragons

[edit]Dragons (or "worms") appear in several varieties, distinguished by whether they have wings and whether they breathe fire (cold-drakes versus fire-drakes). The first of the fire-drakes (Urulóki in Quenya)[T 27] was Glaurung the Golden, bred by Morgoth in Angband, and called "The Great Worm", "The Worm of Morgoth", and "The Father of Dragons".[T 28]

Sapient animals

[edit]Middle-earth contains sapient animals including the Eagles,[T 29] Huan the Great Hound from Valinor and the wolf-like Wargs.[27] In general the origins and nature of these animals are unclear. Giant spiders such as Shelob descended from Ungoliant, of unknown origin.[T 30] Other sapient species include the Crebain, evil crows who become spies for Saruman, and the Ravens of Erebor, who brought news to the Dwarves. The horse-line of the Mearas of Rohan, especially Gandalf's mount, Shadowfax, also appear to be intelligent and understand human speech. The bear-man Beorn had a number of animal friends about his house.[28]

Adaptations

[edit]Motion pictures

[edit]The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, both set in Middle-earth, have been the subject of a variety of film adaptations. There were many early failed attempts to bring the fictional universe to life on screen, some even rejected by the author himself, who was skeptical of the prospects of an adaptation. While animated and live-action shorts were made of Tolkien's books in 1967 and 1971, the first commercial depiction of The Hobbit onscreen was the Rankin/Bass animated TV special in 1977.[29] In 1978 the first big screen adaptation of the fictional setting was introduced in Ralph Bakshi's animated The Lord of the Rings.[30]

New Line Cinema released the first part of director Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film series in 2001 as part of a trilogy; it was followed by a prequel trilogy in The Hobbit film series with several of the same actors playing their old roles.[31] In 2003, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King received 11 Academy Award nominations and won all of them, matching the totals awarded to Ben-Hur and Titanic.[32]

Two well-made fan films of Middle-earth, The Hunt for Gollum and Born of Hope, were uploaded to YouTube on 8 May 2009 and 11 December 2009 respectively.[33][34]

Games

[edit]Numerous computer and video games have been inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien's works set in Middle-earth. Titles have been produced by studios such as Electronic Arts, Vivendi Games, Melbourne House, and Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment.[35][36] Aside from officially licensed games, many Tolkien-inspired mods, custom maps and total conversions have been made for many games, such as Warcraft III, Minecraft,[37] Rome: Total War, Medieval II: Total War, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. In addition, there are many text-based MMORPGs (known as MU*s) based on Middle-earth. The oldest of these dates back to 1991, and was known as Middle-earth MUD, run by using LPMUD.[38] After the Middle-earth MUD ended in 1992, it was followed by Elendor[39] and MUME.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Carpenter 2023, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958, last footnote

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1977, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #165 to the Houghton Mifflin Co., 30 June 1955

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #297 draft for a letter to a 'Mr Rang', August 1967

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #151 to Hugh Brogan, 18 September 1954; #183, Notes on W. H. Auden's review of The Return of the King, 1956; and #283 to Benjamin P. Indick, 7 January 1966

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954a, "Prologue"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #137 to Rayner Unwin, 11 April 1953; #139 to Rayner Unwin, 8 August 1953; #141 to Allen & Unwin, 9 October 1953; #144 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April 1954; #160 to Rayner Unwin, 6 March 1955; #161 to Rayner Unwin, 18 April 1955

- ^ Tolkien 1954, foldout map in first edition

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #169 to Hugh Brogan, 11 September 1955

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #183 notes on W. H. Auden's review of The Return of the King, 1956

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #294 to Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, 8 February 1967

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #190 to Rayner Unwin, 3 July 1956

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, "Prologue"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix D, "Calendars"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, p. 44 "Menelmacar with his shining belt"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, p. 45 "And high in the north as a challenge to Melkor she set the crown of seven mighty stars to swing, Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar..."

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 8 "Strider" "The Sickle [The Hobbits' name for the Plough or Great Bear] was swinging bright above the shoulders of Bree-hill."

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, p. 388

- ^ Tolkien 1954, Book 3, ch. 3 "The Uruk-Hai"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6 ch. 8 "The Scouring of the Shire"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, index entry Urulóki

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 24 "Of the Voyage of Eärendil"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 4, chapter 9: "Shelob's Lair."

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b Christopher, Joe R. (2012). "The Journeys To and From Purgatory Island: A Dantean Allusion at the End of C. S. Lewis's 'The Nameless Isle'". In Khoddam, Salwa; Hall, Mark R.; Fisher, Jason (eds.). C. S. Lewis and the Inklings: Discovering Hidden Truth. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4438-4431-4.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Midgard". Online Etymological Dictionary; etymonline.com. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ a b Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-19-861069-4.

- ^ a b Bratman, David (2013) [2007]. "History of Middle-earth: Overview". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ a b Harvey, Greg (2011). The Origins of Tolkien's Middle-earth For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. Chapter 1: The Worlds of Middle-earth. ISBN 978-1-118-06898-4.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 98.

- ^ Morris, William (2015). Delphi Complete Works of William Morris (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 5104. ISBN 978-1-910630-92-1.

- ^ "The Old Road to Paradise by Margaret Widdemer".

- ^ Ford, G. L. (17 January 2020). "Christopher Tolkien, 1924-2020 Keeper of Middle-earth's Legacy". Book and Film Globe. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

Lewis's Space Trilogy drew on Tolkien's Middle-earth lore at several points, where he used it to deepen the mythology underlying his action.

- ^ a b Hammond, Wayne G.; Anderson, Douglas A. (1993). J.R.R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. St. Paul's Bibliographies. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-873040-11-9.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ Bolintineanu, Alexandra (2013). "Arda". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #168 to Richard Jeffery, 7 September 1966

- ^ Flood, Alison (23 October 2015). "Tolkien's annotated map of Middle-earth discovered inside copy of Lord of the Rings". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 8–11. ISBN 0140038779.

- ^ Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-1403946713.

- ^ West, Richard C. (2006). "'And All the Days of Her Life Are Forgotten': 'The Lord of the Rings' as Mythic Prehistory". In Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). The Lord of the Rings, 1954-2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder. Marquette University Press. pp. 67–100. ISBN 978-0-87462-018-4. OCLC 298788493.

- ^ Eden, Bradford Lee (2013) [2007]. "Elves". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Dickerson, Matthew (2013) [2007]. "Elves: Kindreds and Migrations". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2013) [2007]. "Men, Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 414–417. ISBN 978-1-135-88034-7.

- ^ Evans, Jonathan (2013) [2007]. "Dwarves". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Stanton, Michael N. (2013) [2007]. "Hobbits". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 280–282. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 159.

- ^ Tally, Robert T. Jr. (2010). "Let Us Now Praise Famous Orcs: Simple Humanity in Tolkien's Inhuman Creatures". Mythlore. 29 (1). article 3.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 362, 438 (chapter 5, note 14).

- ^ Evans, Jonathan. "Monsters". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. p. 433.

- ^ Burns, Marjorie (2013) [2007]. "Old Norse Literature". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 473–474. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

Echoes of these Norse battle animals appear throughout Tolkien's literature; in one way or another, all are associated with Gandalf or his cause. ... raven ... Eagles ... wolves ... horses ... Saruman is the one most closely associated with Odin's ravaging wolves and carrion birds

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (25 November 1977). "TV Weekend: "The Hobbit"". The New York Times.

- ^ Gaslin, Glenn (21 November 2001). "Ralph Bakshi's unfairly maligned Lord of the Rings". Slate. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Timmons, Daniel (2013) [2007]. "Jackson, Peter". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 303–310. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ "Here Are The Biggest Academy Award Milestones In Oscars History". Hollywood.Com. 3 February 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Sydell, Laura (30 April 2009). "High-Def 'Hunt For Gollum' New Lord of the Fanvids". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ Martin, Nicole (27 October 2008). "Orcs are back in Lord of the Rings-inspired Born of Hope". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (15 June 2017). "Warner Bros. games are coming out of the shadow of its movies". GamesBeat. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (3 July 2017). "Warner Bros., Tolkien Estate Settle $80 Million 'Hobbit' Lawsuit". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Bauer, Manuel (10 September 2015). "Minecraft: Spieler haben das komplette Auenland nachgebaut". Computer Bild. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Groups.google.com, rec.games.mud.lp Newsgroup, 1 June 1994

- ^ Davis, Erik (1 October 2001). "The Fellowship of the Ring". Wired.

- ^ For a (rather long) list of all the Tolkien inspired MU*s go to The Mud Connector Archived 26 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine and run a search for 'tolkien'.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. G. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3. OCLC 3046822.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-earth (3nd ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1981). The Atlas of Middle-earth (1st ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-28665-4.

- Garth, John (2020). The Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. London: Frances Lincoln Publishers. ISBN 978-0-71124-127-5.

- Foster, Robert (2001) [1978]. The Complete Guide to Middle-earth. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-44976-2.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2004) [1995]. J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-261-10322-9.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion (1st ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-720907-X.