Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

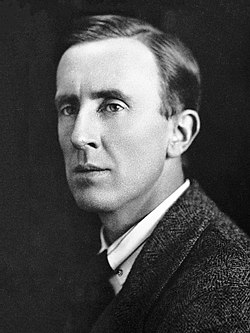

J. R. R. Tolkien

View on Wikipedia

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (/ˈruːl ˈtɒlkiːn/,[a] 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Key Information

From 1925 to 1945 Tolkien was the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon and a Fellow of Pembroke College, both at the University of Oxford. He then moved within the same university to become the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature and Fellow of Merton College, and held these positions from 1945 until his retirement in 1959. Tolkien was a close friend of C. S. Lewis, a co-member of the Inklings, an informal literary discussion group. He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II on 28 March 1972.

After Tolkien's death his son Christopher published a series of works based on his father's extensive notes and unpublished manuscripts, including The Silmarillion. These, together with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, form a connected body of tales, poems, fictional histories, invented languages, and literary essays about a fantasy world called Arda and, within it, Middle-earth. Between 1951 and 1955 Tolkien applied the term legendarium to the larger part of these writings.

While many other authors had published works of fantasy before Tolkien, the tremendous success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings ignited a profound interest in the fantasy genre and ultimately precipitated an avalanche of new fantasy books and authors. As a result he has been popularly identified as the "father" of modern fantasy literature and is widely regarded as one of the most influential authors of all time.

Biography

[edit]Ancestry

[edit]Tolkien was English, and thought of himself as such.[3][T 1] His immediate paternal ancestors were middle-class craftsmen who made and sold clocks, watches and pianos in London and Birmingham. The Tolkien family originated in the East Prussian town of Kreuzburg near Königsberg, which had been founded during the medieval German eastward expansion, where his earliest-known paternal ancestor, Michel Tolkien, was born around 1620.[4]

In 1792 John Benjamin Tolkien and William Gravell took over the Erdley Norton manufacture in London, which from then on sold clocks and watches under the name Gravell & Tolkien. John Benjamin's brother Daniel Gottlieb Tolkien obtained British citizenship in 1794, but John Benjamin Tolkien apparently never became a British citizen. Other German relatives joined the two brothers in London. Several people with the surname Tolkien or similar spelling, some of them members of the same family as J. R. R. Tolkien, live in northern Germany, but most of them are descendants of people who were evacuated from East Prussia in 1945, at the end of the Second World War.[5][4][6]

According to Ryszard Derdziński, the surname Tolkien is of Low Prussian origin and probably means "son/descendant of Tolk".[5][4] Tolkien mistakenly believed his surname derived from the German word tollkühn, meaning "foolhardy",[7] and jokingly inserted himself as a "cameo" into The Notion Club Papers under the literally translated name Rashbold.[8] However, Derdziński has demonstrated this to be a false etymology. Another suspected origin is the East Prussian village of Tołkiny.[9] While J. R. R. Tolkien was aware of his family's German origin, his knowledge of the family's history was limited because he was "early isolated from the family of his prematurely deceased father".[5][4]

Childhood

[edit]

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born on 3 January 1892 in Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State (later annexed by the British Empire; now Free State Province in the Republic of South Africa), to Arthur Reuel Tolkien, an English bank manager, and his wife Mabel, née Suffield. The couple had left England when Arthur was promoted to head the Bloemfontein office of the British bank for which he worked. Tolkien had one sibling, his younger brother, Hilary Arthur Reuel Tolkien, who was born on 17 February 1894.[10]

As a child Tolkien was bitten by a large baboon spider in the garden, an event some believe to have been later echoed in his stories, although he admitted no actual memory of the event as an adult. In an earlier incident from Tolkien's infancy, a young family servant took the baby to his homestead, returning him the next morning.[11]

When he was three, he went to England with his mother and brother on what was intended to be a lengthy family visit. His father, however, died in South Africa of rheumatic fever before he could join them.[12] This left the family without an income, so Tolkien's mother took him to live with her parents in Kings Heath,[13] Birmingham. Soon after, in 1896, they moved to Sarehole (now in Hall Green), then a Worcestershire village, later annexed to Birmingham.[14] He enjoyed exploring Sarehole Mill and Moseley Bog and the Clent, Lickey and Malvern Hills, which would later inspire scenes in his books, along with nearby towns and villages such as Bromsgrove, Alcester and Alvechurch and places such as his aunt Jane's farm Bag End, the name of which he used in his fiction.[15]

Mabel Tolkien taught her two children at home. Ronald, as he was known in the family, was a keen pupil.[16] She taught him a great deal of botany and awakened in him the enjoyment of the look and feel of plants. Young Tolkien liked to draw landscapes and trees, but his favourite lessons were those concerning languages, and his mother taught him the rudiments of Latin very early.[17]

Tolkien could read by the age of four and could write fluently soon afterwards. His mother allowed him to read many books. He disliked Treasure Island and "The Pied Piper" and thought Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll was "amusing". He liked stories about "Red Indians" (the term then used for Native Americans in adventure stories[18]) and works of fantasy by George MacDonald.[19] In addition, the "Fairy Books" of Andrew Lang were particularly important to him and their influence is apparent in some of his later writings.[20]

Mabel Tolkien was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1900 despite vehement protests by her Baptist family,[21] which stopped all financial assistance to her. In 1904, when J. R. R. Tolkien was 12, his mother died of acute diabetes at Fern Cottage in Rednal, which she was renting. She was then about 34 years of age, about as old as a person with diabetes mellitus type 1 could survive without treatment—insulin would not be discovered until 1921, two decades later. Nine years after her death, Tolkien wrote, "My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith."[21]

Before her death, Mabel Tolkien had assigned the guardianship of her sons to her close friend, Father Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, who was assigned to bring them up as good Catholics.[22] In a 1965 letter to his son Michael, Tolkien recalled the influence of the man whom he always called "Father Francis": "He was an upper-class Welsh-Spaniard Tory, and seemed to some just a pottering old gossip. He was—and he was not. I first learned charity and forgiveness from him; and in the light of it pierced even the 'liberal' darkness out of which I came, knowing more about 'Bloody Mary' than the Mother of Jesus—who was never mentioned except as an object of wicked worship by the Romanists."[T 2] After his mother's death, Tolkien grew up in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham and attended King Edward's School, Birmingham, and later St Philip's School. In 1903, he won a Foundation Scholarship and returned to King Edward's.[23]

Youth

[edit]

While in his early teens, Tolkien had his first encounter with a constructed language, Animalic, an invention of his cousins, Mary and Marjorie Incledon. At that time, he was studying Latin and Anglo-Saxon. Their interest in Animalic soon died away, but Mary and others, including Tolkien himself, invented a new and more complex language called Nevbosh. The next constructed language he came to work with, Naffarin, would be his own creation.[25][26] Tolkien learned Esperanto some time before 1909. Around 10 June 1909 he composed "The Book of the Foxrook", a sixteen-page notebook, where the "earliest example of one of his invented alphabets" appears.[27] Short texts in this notebook are written in Esperanto.[28]

In 1911, while they were at King Edward's School, Tolkien and three friends, Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Bache Smith, and Christopher Wiseman, formed a semi-secret society they called the T.C.B.S. The initials stood for Tea Club and Barrovian Society, alluding to their fondness for drinking tea in Barrow's Stores near the school and, secretly, in the school library.[29][30] After leaving school, the members stayed in touch and, in December 1914, they held a council in London at Wiseman's home. For Tolkien, the result of this meeting was a strong dedication to writing poetry.[31]

In 1911, Tolkien went on a summer holiday in Switzerland, a trip that he recollected vividly in a 1968 letter,[T 3] noting that Bilbo's journey across the Misty Mountains ("including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods") is directly based on his adventures as their party of 12 hiked from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen and on to camp in the moraines beyond Mürren. Fifty-seven years later, Tolkien remembered his regret at leaving the view of the eternal snows of Jungfrau and Silberhorn, "the Silvertine (Celebdil) of my dreams". They went across the Kleine Scheidegg to Grindelwald and on across the Grosse Scheidegg to Meiringen. They continued across the Grimsel Pass, through the upper Valais to Brig and on to the Aletsch glacier and Zermatt.[32]

In October of the same year, Tolkien began studying at Exeter College, Oxford. He initially read classics but changed his course in 1913 to English language and literature, graduating in 1915 with first-class honours.[33] Among his tutors at Oxford was Joseph Wright, whose Primer of the Gothic Language had inspired Tolkien as a schoolboy.[34]

Courtship and marriage

[edit]At the age of 16, Tolkien met Edith Mary Bratt, who was three years his senior, when he and his brother Hilary moved into the boarding house where she lived in Duchess Road, Edgbaston. According to Humphrey Carpenter, "Edith and Ronald took to frequenting Birmingham teashops, especially one which had a balcony overlooking the pavement. There they would sit and throw sugarlumps into the hats of passers-by, moving to the next table when the sugar bowl was empty. ... With two people of their personalities and in their position, romance was bound to flourish. Both were orphans in need of affection, and they found that they could give it to each other. During the summer of 1909, they decided that they were in love."[35]

His guardian, Father Morgan, considered it "altogether unfortunate"[T 4] that his surrogate son was romantically involved with an older, Protestant woman; Tolkien wrote that the combined tensions contributed to his having "muffed [his] exams".[T 4] Morgan prohibited him from meeting, talking to, or even corresponding with Edith until he was 21. Tolkien obeyed this prohibition to the letter,[36] with one notable early exception, over which Father Morgan threatened to cut short his university career if he did not stop.[37]

On the evening of his 21st birthday Tolkien wrote to Edith, who was living with a family friend named C. H. Jessop in Cheltenham. He declared that he had never ceased to love her, and asked her to marry him. Edith replied that she had already accepted the proposal of George Field, the brother of one of her closest school friends. But Edith said she had agreed to marry Field only because she felt "on the shelf" and had begun to doubt that Tolkien still cared for her. She explained that, because of Tolkien's letter, everything had changed.[38]

On 8 January 1913 Tolkien travelled by train to Cheltenham and was met on the platform by Edith. The two took a walk into the countryside, sat under a railway viaduct, and talked. By the end of the day, Edith had agreed to accept Tolkien's proposal. She wrote to Field and returned her engagement ring. Field was "dreadfully upset at first", and the Field family was "insulted and angry".[38] Upon learning of Edith's new plans, Jessop wrote to her guardian, "I have nothing to say against Tolkien, he is a cultured gentleman, but his prospects are poor in the extreme, and when he will be in a position to marry I cannot imagine. Had he adopted a profession it would have been different."[39]

Following their engagement, Edith reluctantly announced that she was converting to Catholicism at Tolkien's insistence. Jessop, "like many others of his age and class ... strongly anti-Catholic", was infuriated, and he ordered Edith to find other lodgings.[40]

Edith Bratt and Ronald Tolkien were formally engaged at Birmingham in January 1913, and married at St Mary Immaculate Catholic Church at Warwick, on 22 March 1916.[41] In his 1941 letter to Michael, Tolkien expressed admiration for his wife's willingness to marry a man with no job, little money, and no prospects except the likelihood of being killed in the Great War.[T 4]

First World War

[edit]

In August 1914 Britain entered the First World War. Tolkien's relatives were shocked when he elected not to volunteer immediately for the British Army. In a 1941 letter to his son Michael, Tolkien recalled: "In those days chaps joined up, or were scorned publicly. It was a nasty cleft to be in for a young man with too much imagination and little physical courage."[T 4] Instead, Tolkien, "endured the obloquy",[T 4] and entered a programme by which he delayed enlistment until completing his degree. By the time he passed his finals in July 1915, Tolkien recalled that the hints were "becoming outspoken from relatives".[T 4] He was commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers on 15 July 1915.[42][43] He trained with the 13th (Reserve) Battalion on Cannock Chase, Rugeley Camp near to Rugeley, Staffordshire, for 11 months. In a letter to Edith, Tolkien complained: "Gentlemen are rare among the superiors, and even human beings rare indeed."[44] Following their wedding Lieutenant and Mrs. Tolkien took up lodgings near the training camp.[42] On 2 June 1916 Tolkien received a telegram summoning him to Folkestone for posting to France. The Tolkiens spent the night before his departure in a room at the Plough & Harrow Hotel in Edgbaston, Birmingham.[45] He later wrote: "Junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute. Parting from my wife then ... it was like a death."[46]

France

[edit]On 5 June 1916 Tolkien boarded a troop transport for an overnight voyage to Calais. Like other soldiers arriving for the first time, he was sent to the British Expeditionary Force's base depot at Étaples. On 7 June, he was informed that he had been assigned as a signals officer to the 11th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers. The battalion was part of the 74th Brigade, 25th Division. While waiting to be summoned to his unit, Tolkien sank into boredom. To pass the time, he composed a poem titled The Lonely Isle, which was inspired by his feelings during the sea crossing to Calais. To evade the British Army's postal censorship, he developed a code of dots by which Edith could track his movements.[47] He left Étaples on 27 June 1916 and joined his battalion at Rubempré, near Amiens.[48] He found himself commanding enlisted men who were drawn mainly from the mining, milling, and weaving towns of Lancashire.[49] According to John Garth, he "felt an affinity for these working class men", but military protocol prohibited friendships with "other ranks". Instead, he was required to "take charge of them, discipline them, train them, and probably censor their letters ... If possible, he was supposed to inspire their love and loyalty."[50] Tolkien later lamented, "The most improper job of any man ... is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity."[50]

Battle of the Somme

[edit]

Tolkien arrived at the Somme in early July 1916. In between terms behind the lines at Bouzincourt, he participated in the assaults on the Schwaben Redoubt and the Leipzig salient. Tolkien's time in combat was a terrible stress for Edith, who feared that every knock on the door might carry news of her husband's death. Edith could track her husband's movements on a map of the Western Front. The Reverend Mervyn S. Evers, Anglican chaplain to the Lancashire Fusiliers, recorded that Tolkien and his fellow officers were eaten by "hordes of lice" which found the Medical Officer's ointment merely "a kind of hors d'oeuvre and the little beggars went at their feast with renewed vigour."[51] On 27 October 1916, as his battalion attacked Regina Trench, Tolkien contracted trench fever, a disease carried by lice. He was invalided to England on 8 November 1916.[52]

According to his children John and Priscilla Tolkien, "In later years, he would occasionally talk of being at the front: of the horrors of the first German gas attack, of the utter exhaustion and ominous quiet after a bombardment, of the whining scream of the shells, and the endless marching, always on foot, through a devastated landscape, sometimes carrying the men's equipment as well as his own to encourage them to keep going. ... Some remarkable relics survive from that time: a trench map he drew himself; pencil-written orders to carry bombs to the 'fighting line.'"[53]

Many of his dearest school friends were killed in the war. Among their number were Rob Gilson of the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, who was killed on the first day of the Somme while leading his men in the assault on Beaumont Hamel. Fellow T.C.B.S. member Geoffrey Smith was killed during the battle, when a German artillery shell landed on a first-aid post. Tolkien's battalion was almost completely wiped out following his return to England.[54]

According to John Garth, Kitchener's Army, in which Tolkien served, at once marked existing social boundaries and counteracted the class system by throwing everyone into a desperate situation together. Tolkien was grateful, writing that it had taught him "a deep sympathy and feeling for the Tommy; especially the plain soldier from the agricultural counties".[55]

Home front

[edit]A weak and emaciated Tolkien spent the remainder of the war alternating between hospitals and garrison duties, being deemed medically unfit for general service.[56][57][58] During his recovery in a cottage in Little Haywood, Staffordshire, he began to work on what he called The Book of Lost Tales, beginning with The Fall of Gondolin. Lost Tales represented Tolkien's attempt to create a mythology for England, a project he would abandon without ever completing.[59] Throughout 1917 and 1918 his illness kept recurring, but he had recovered enough to do home service at various camps. It was at this time that Edith bore their first child, John Francis Reuel Tolkien. In a 1941 letter, Tolkien described his son John as "(conceived and carried during the starvation-year of 1917 and the great U-boat campaign) round about the Battle of Cambrai, when the end of the war seemed as far off as it does now".[T 4] Tolkien was promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant on 6 January 1918.[60] When he was stationed at Kingston upon Hull, he and Edith went walking in the woods at nearby Roos, and Edith began to dance for him in a clearing among the flowering hemlock. After his wife's death in 1971, Tolkien remembered:[T 5]

I never called Edith Luthien—but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks[61] at Roos in Yorkshire (where I was for a brief time in command of an outpost of the Humber Garrison in 1917, and she was able to live with me for a while). In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing—and dance. But the story has gone crooked, & I am left, and I cannot plead before the inexorable Mandos.[T 5]

On 16 July 1919, Tolkien was taken off active service, at Fovant, on Salisbury Plain, with a temporary disability pension.[62] On 3 November 1920, Tolkien was demobilized and left the army, retaining his rank of lieutenant.[63]

Academic and writing career

[edit]

After the end of the war in 1918, Tolkien's first civilian job was at the Oxford English Dictionary, where he worked mainly on the history and etymology of words of Germanic origin beginning with the letter W.[64] In mid-1919, he began to tutor Oxford undergraduates privately, most importantly those of Lady Margaret Hall and St Hugh's College, given that the women's colleges were in great need of good teachers in their early years, and Tolkien as a married academic (then still not common) was considered suitable, as a bachelor don would not have been.[65]

In 1920 he took up a post as reader in English language at the University of Leeds, becoming the youngest member of the academic staff there.[66] While at Leeds, he produced A Middle English Vocabulary and a definitive edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with E. V. Gordon; both became academic standard works for several decades. He also translated Sir Gawain, Pearl and Sir Orfeo, but the translations were not published until 1975. In 1924 he was promoted from a readership at Leeds to a professorship.[67]

In October 1925 he returned to Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, with a fellowship at Pembroke College.[68] During his time at Pembroke College Tolkien wrote The Hobbit and the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings, while living at 20 Northmoor Road in North Oxford. In 1932 he published a philological essay on the name "Nodens", following Sir Mortimer Wheeler's unearthing of a Roman Asclepeion at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, in 1928.[69]

Beowulf

[edit]In the 1920s Tolkien undertook a translation of Beowulf, which he finished in 1926, but did not publish. It was later edited by his son Christopher and published in 2014.[70]

Ten years after finishing his translation, Tolkien gave a highly acclaimed lecture on the work, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics", which had a lasting influence on Beowulf research.[71] Lewis E. Nicholson said that the article is "widely recognized as a turning point in Beowulfian criticism", noting that Tolkien established the primacy of the poetic nature of the work as opposed to its purely linguistic elements.[72] At the time, the consensus of scholarship deprecated Beowulf for dealing with childish battles with monsters rather than realistic tribal warfare; Tolkien argued that the author of Beowulf was addressing human destiny in general, not as limited by particular tribal politics, and therefore the monsters were essential to the poem.[73] Where Beowulf does deal with specific tribal struggles, as at Finnsburg, Tolkien argued firmly against reading in fantastic elements.[74] In the essay, Tolkien revealed how highly he regarded Beowulf: "Beowulf is among my most valued sources"; this influence may be seen throughout his Middle-earth legendarium.[75]

According to Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien began his series of lectures on Beowulf in a most striking way, entering the room silently, fixing the audience with a look, and suddenly declaiming in Old English the opening lines of the poem, starting "with a great cry of Hwæt!" It was a dramatic impersonation of an Anglo-Saxon bard in a mead hall, and it made the students realize that Beowulf was not just a set text but "a powerful piece of dramatic poetry".[76] Decades later, W. H. Auden wrote to his former professor, thanking him for the "unforgettable experience" of hearing him recite Beowulf, and stating: "The voice was the voice of Gandalf".[76]

Second World War

[edit]

In the run-up to the Second World War Tolkien was earmarked as a codebreaker. In January 1939 he was asked to serve in the cryptographic department of the Foreign Office in the event of national emergency. Beginning on 27 March, he took an instructional course at the London headquarters of the Government Code and Cypher School. He was informed in October that his services would not be required.[77][T 6][78]

In 1945 Tolkien moved to Merton College, Oxford, becoming the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature,[79] in which post he remained until his retirement in 1959. He served as an external examiner for University College, Galway (now the University of Galway), for many years.[80] In 1954 Tolkien received an honorary degree from the National University of Ireland (of which University College, Galway, was a constituent college).[81] Tolkien completed The Lord of the Rings in 1948, close to a decade after the first sketches.[82]

Family

[edit]The Tolkiens had four children: John Francis Reuel Tolkien (17 November 1917 – 22 January 2003), Michael Hilary Reuel Tolkien (22 October 1920 – 27 February 1984), Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (21 November 1924 – 16 January 2020) and Priscilla Mary Anne Reuel Tolkien (18 June 1929 – 28 February 2022).[83][84] Tolkien was very devoted to his children and sent them illustrated letters from Father Christmas when they were young.[85]

Retirement

[edit]

During his life in retirement, from 1959 up to his death in 1973, Tolkien received steadily increasing public attention and literary fame. In 1961 his friend C. S. Lewis even nominated him for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[86] The sales of his books were so profitable that he regretted that he had not chosen early retirement.[17] In a letter in 1972 he deplored having become a cult figure, but admitted that "even the nose of a very modest idol ... cannot remain entirely untickled by the sweet smell of incense!"[T 7]

Fan attention became so intense that Tolkien had to take his phone number out of the public directory;[T 8] eventually he and Edith moved to Bournemouth, which was then a seaside resort patronized by the British upper middle class. Tolkien's status as a best-selling author gave them easy entry into polite society, but Tolkien deeply missed the company of his fellow Inklings. Edith, however, was overjoyed to step into the role of a society hostess, which had been the reason that Tolkien selected Bournemouth in the first place. The genuine and deep affection between Ronald and Edith was demonstrated by their care about the other's health, in details like wrapping presents, in the generous way he gave up his life at Oxford so she could retire to Bournemouth, and in her pride in his becoming a famous author. They were tied together, too, by love for their children and grandchildren.[87]

In his retirement Tolkien was a consultant and translator for The Jerusalem Bible, published in 1966. He was initially assigned a larger portion to translate, but, due to other commitments, only managed to offer some criticisms of other contributors and a translation of the Book of Jonah.[T 9]

Final years

[edit]

Edith died on 29 November 1971, at the age of 82. Ronald returned to Oxford, where Merton College gave him convenient rooms near the High Street. He missed Edith, but enjoyed being back in the city.[88]

Tolkien was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1972 New Year Honours[89] and received the insignia of the Order at Buckingham Palace on 28 March 1972.[T 10] In the same year Oxford University gave him an honorary Doctorate of Letters.[33][90]

He had the name Luthien [sic] engraved on Edith's tombstone at Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. When Tolkien died 21 months later on 2 September 1973 from a bleeding ulcer and chest infection,[91] at the age of 81,[92] he was buried in the same grave, with "Beren" added to his name. Tolkien's will was proven on 20 December 1973, with his estate valued at £190,577 (equivalent to £2,454,000 in 2023).[93][94]

Views

[edit]

Religion

[edit]Tolkien's Catholicism was a significant factor in C. S. Lewis's conversion from atheism to Christianity.[95] He once wrote to Rayner Unwin's daughter Camilla, who wished to know the purpose of life, that it was "to increase according to our capacity our knowledge of God by all the means we have, and to be moved by it to praise and thanks."[96] He had a special devotion to the blessed sacrament, writing to his son Michael that in "the Blessed Sacrament ... you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that".[T 4] He accordingly encouraged frequent reception of Holy Communion, again writing to his son Michael that "the only cure for sagging of fainting faith is Communion." He believed the Catholic Church to be true most of all because of the pride of place and the honour in which it holds the Blessed Sacrament.[T 11] In the last years of his life Tolkien resisted certain liturgical changes implemented after the Second Vatican Council, his primary objection being the use of English for the liturgy.[97] Tolkien spoke Latin fluently, and he felt that the English translations were clumsy.[98] In his old age he continued to make the Mass responses in Latin.[88][99] Tolkien did not sign the Agatha Christie indult, however, and he served as a lector at Corpus Christi, a parish church in Headington, in accordance with the allowances of the Council.[100]

Government

[edit]Tolkien held deeply skeptical views of political authority, writing that "the most improper job of any man, even saints, is bossing other men".[101] He distrusted both mass democracy and centralized state power, writing that not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity".[102][101] In one of his letters, Tolkien described his political leanings as "more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs)".[T 12][102][103] He explained that he was "not a democrat, only because humility and equality are spiritual principles, not political ones".[102]

Tolkien believed small-scale, community policing was more effective than state-control.[102] He also believed that power itself, even when well-intentioned, carries a corrupting influence. This philosophical theme runs through The Lord of the Rings, where Tolkien writes that Gandalf rejects using the One Ring for good due to its ability to corrupt.[104][102] The books also portray the desire to dominate others as the original and enduring temptation of evil.

Race

[edit]Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy writings have been said to embody outmoded attitudes to race.[105] However, scholars have noted that he was influenced by Victorian attitudes to race and to a literary tradition of monsters, and that he was anti-racist both in peacetime and during the two World Wars. With the late-19th-century background of eugenics and a fear of moral decline, some critics believed that the mention of race mixing in The Lord of the Rings embodied scientific racism.[106] Critics have noted, too, that the work embodies a moral geography, with good in the West, evil in the East.[107] Against this, Tolkien strongly opposed Nazi racial theories, as seen in a 1938 letter he wrote to his publisher, while during the Second World War he vigorously opposed anti-German propaganda.[108][109] His Middle-earth has been described as definitely polycultural and polylingual, while scholars have noted that attacks on Tolkien based on The Lord of the Rings often omit relevant evidence from the text.[110][111] A spokesman for HarperCollins, publisher of the trilogy, said: "A number of academics have commented on Tolkien's work and this is the first time anybody has ever seen these issues in it. Of course, if you look hard enough at many great epics, you can extrapolate what you like, particularly if you have academic kudos behind you."[112]

Nature

[edit]During most of his own life, conservationism was not yet on the political agenda, and Tolkien himself did not directly express conservationist views—except in some private letters, in which he tells about his fondness for forests and sadness at tree-felling. In later years, a number of authors of biographies or literary analyses of Tolkien conclude that during his writing of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien gained increased interest in the value of wild and untamed nature, and in protecting what wild nature was left in the industrialized world.[113][114][115]

Writing

[edit]Influences

[edit]Tolkien's fantasy books on Middle-earth, especially The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, drew on a wide array of influences, including his philological interest in language,[116] Christianity,[117][118] medievalism,[119] mythology, archaeology,[120] ancient and modern literature and personal experience. His philological work centred on the study of Old English literature, especially Beowulf, and he acknowledged its importance to his writings.[121] He was a gifted linguist, influenced by Germanic,[122] Celtic,[123] Finnish,[124] and Greek[125][126] language and mythology. Commentators have attempted to identify many literary and topological antecedents for characters, places and events in Tolkien's writings. Some writers were important to him, including the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris,[127] and he undoubtedly made use of some real place-names, such as Bag End, the name of his aunt's home.[128] He acknowledged, too, John Buchan and H. Rider Haggard, authors of Edwardian adventure stories that he enjoyed.[129][130][131] The effects of some specific experiences have been identified. Tolkien's childhood in the English countryside, and its urbanization by the growth of Birmingham, influenced his creation of the Shire,[132] while his personal experience of fighting in the trenches of the First World War affected his depiction of Mordor.[133]

Publications

[edit]"Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics"

[edit]In addition to writing fiction, Tolkien was an author of academic literary criticism. His seminal 1936 lecture, later published as an article, revolutionized the treatment of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf by literary critics. The essay remains highly influential in the study of Old English literature to this day.[134] Beowulf is one of the most significant influences upon Tolkien's later fiction, with major details of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings being adapted from the poem.[135]

"On Fairy-Stories"

[edit]This essay discusses the fairy-story as a literary form. It was initially written as the 1939 Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. Tolkien focuses on Andrew Lang's work as a folklorist and collector of fairy tales. He disagreed with Lang's broad inclusion, in his Fairy Book collections, of traveller's tales, beast fables, and other types of stories. Tolkien held a narrower perspective, viewing fairy stories as those that took place in Faerie, an enchanted realm, with or without fairies as characters. He viewed them as the natural development of the interaction of human imagination and human language.[136]

Children's books and other short works

[edit]In addition to his mythopoeic compositions, Tolkien enjoyed inventing fantasy stories to entertain his children.[137] He wrote annual Christmas letters from Father Christmas for them, building up a series of short stories (later compiled and published as The Father Christmas Letters).[138] Other works included Mr. Bliss and Roverandom (for children), and Leaf by Niggle (part of Tree and Leaf), The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham. Roverandom and Smith of Wootton Major, like The Hobbit, borrowed ideas from his legendarium.[139]

The Hobbit

[edit]Tolkien never expected his stories to become popular, but by sheer accident a book called The Hobbit, which he had written some years before for his own children, came in 1936 to the attention of Susan Dagnall, an employee of the London publishing firm George Allen & Unwin, who persuaded Tolkien to submit it for publication.[92] When it was published a year later, the book attracted adult readers as well as children, and it became popular enough for the publishers to ask Tolkien to produce a sequel.[140]

The Lord of the Rings

[edit]The request for a sequel prompted Tolkien to begin what became his most famous work: the epic novel The Lord of the Rings (originally published in three volumes in 1954–1955). Tolkien spent more than ten years writing the primary narrative and appendices for The Lord of the Rings, during which time he received the constant support of the Inklings, in particular his closest friend C. S. Lewis, the author of The Chronicles of Narnia. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set against the background of The Silmarillion, but in a time long after it.[141]

Tolkien at first intended The Lord of the Rings to be a children's tale in the style of The Hobbit, but it quickly grew darker and more serious in the writing.[142] Though a direct sequel to The Hobbit, it addressed an older audience, drawing on the immense backstory of Beleriand that Tolkien had constructed in previous years, and which eventually saw posthumous publication in The Silmarillion and other volumes.[141] Tolkien strongly influenced the fantasy genre that grew up after the book's success.[143]

The Lord of the Rings became immensely popular in the 1960s and has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the 20th century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[144] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the UK's "Best-loved Novel".[145] Australians voted The Lord of the Rings "My Favourite Book" in a 2004 survey conducted by the Australian ABC.[146] In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium".[147] In 2002 Tolkien was voted the 92nd "greatest Briton" in a poll conducted by the BBC, and in 2004 he was voted 35th in the SABC3's Great South Africans, the only person to appear in both lists. His popularity is not limited to the English-speaking world: in a 2004 poll inspired by the UK's "Big Read" survey, about 250,000 Germans found The Lord of the Rings to be their favourite work of literature.[148]

The Silmarillion

[edit]Tolkien wrote a brief "Sketch of the Mythology", which included the tales of Beren and Lúthien and of Túrin; and that sketch eventually evolved into the Quenta Silmarillion, an epic history that Tolkien started three times but never published. Tolkien desperately hoped to publish it along with The Lord of the Rings, but publishers (both Allen & Unwin and Collins) declined. Moreover, printing costs were very high in 1950s Britain, requiring The Lord of the Rings to be published in three volumes.[149] The story of this continuous redrafting is told in the posthumous series The History of Middle-earth, edited by Tolkien's son, Christopher Tolkien. From around 1936, Tolkien began to extend this framework to include the tale of The Fall of Númenor, which was inspired by the legend of Atlantis.[150]

Tolkien appointed his son Christopher to be his literary executor, and he (with assistance from Guy Gavriel Kay, later a well-known fantasy author in his own right) organized some of this material into a single coherent volume, published as The Silmarillion in 1977. It received the Locus Award for Best Fantasy novel in 1978.[151]

Unfinished Tales and The History of Middle-earth

[edit]In 1980, Christopher Tolkien published a collection of more fragmentary material, under the title Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth. In subsequent years (1983–1996), he published a large amount of the remaining unpublished materials, together with notes and extensive commentary, in a series of twelve volumes called The History of Middle-earth. They contain unfinished, abandoned, alternative, and outright contradictory accounts, since they were always a work in progress for Tolkien and he only rarely settled on a definitive version for any of the stories. There is not complete consistency between The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, the two most closely related works, because Tolkien never fully integrated all their traditions into each other. He commented in 1965, while editing The Hobbit for a third edition, that he would have preferred to rewrite the book completely because of the style of its prose.[152]

Works compiled by Christopher Tolkien

[edit]| Date | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | The Children of Húrin | Tells the story of Túrin Turambar and his sister Nienor, children of Húrin Thalion.[153] |

| 2009 | The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún | Retells the legend of Sigurd and the fall of the Niflungs from Germanic mythology as a narrative poem in alliterative verse, modelled after the Old Norse poetry of the Elder Edda.[154] |

| 2013 | The Fall of Arthur | A narrative poem that Tolkien composed in the early 1930s, inspired by high medieval Arthurian fiction but set in the Post-Roman Migration Period, showing Arthur as a British warlord fighting the Saxon invasion.[155] |

| 2014 | Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary | A prose translation of Beowulf that Tolkien made in the 1920s, with commentary from Tolkien's lecture notes.[156][157] |

| 2015 | The Story of Kullervo | A retelling of a 19th-century Finnish poem that Tolkien wrote in 1915 while studying at Oxford.[158] |

| 2017 | Beren and Lúthien | One of the oldest and most often revised in Tolkien's legendarium; a version appeared in The Silmarillion.[159] |

| 2018 | The Fall of Gondolin | Tells of a beautiful, mysterious city destroyed by dark forces; Tolkien called it "the first real story" of Middle-earth.[160][161] |

Manuscript locations

[edit]Before his death, Tolkien negotiated the sale of the manuscripts, drafts, proofs and other materials related to his then-published works—including The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit and Farmer Giles of Ham—to the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Marquette University's John P. Raynor, S.J., Library in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States.[162] After his death his estate donated the papers containing Tolkien's Silmarillion mythology and his academic work to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.[163] The Bodleian Library held an exhibition of his work in 2018, including more than 60 items which had never been seen in public before.[164]

In 2009 a partial draft of Language and Human Nature, which Tolkien had begun co-writing with Lewis but had never completed, was discovered at the Bodleian Library.[165]

Languages and philology

[edit]Linguistic career

[edit]Both Tolkien's academic career and his literary production are inseparable from his love of language and philology. He specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as his special subject. He worked on the Oxford English Dictionary from 1918 and is credited with having worked on a number of words starting with the letter W, including walrus, over which he struggled mightily.[166][167] In 1920 he became Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic and Medieval Welsh. When in 1925, aged thirty-three, Tolkien applied for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford, he boasted that his students of Germanic philology in Leeds had even formed a "Viking Club".[T 13] He had a certain, if imperfect, knowledge of Finnish.[168]

Privately, Tolkien was attracted to "things of racial and linguistic significance", and in his 1955 lecture English and Welsh, which is crucial to his understanding of race and language, he entertained notions of "inherent linguistic predilections", which he termed the "native language" as opposed to the "cradle-tongue" which a person first learns to speak.[169] He considered the West Midlands dialect of Middle English to be his own "native language", and, as he wrote to W. H. Auden in 1955, "I am a West-midlander by blood (and took to early west-midland Middle English as a known tongue as soon as I set eyes on it)."[T 14]

Language construction

[edit]Parallel to Tolkien's professional work as a philologist, and sometimes overshadowing this work, to the effect that his academic output remained rather thin, was his affection for constructing languages. The most developed of these are Quenya and Sindarin, the etymological connection between which formed the core of much of Tolkien's legendarium. Language and grammar for Tolkien was a matter of aesthetics and euphony, and Quenya in particular was designed from "phonaesthetic" considerations; it was intended as an "Elven-latin", and was phonologically based on Latin, with ingredients from Finnish, Welsh, English, and Greek.[T 15]

Tolkien considered languages inseparable from the mythology associated with them, and he consequently took a dim view of auxiliary languages: in 1930 a congress of Esperantists were told as much by him, in his lecture A Secret Vice,[170] "Your language construction will breed a mythology", but by 1956 he had concluded that "Volapük, Esperanto, Ido, Novial, &c, &c, are dead, far deader than ancient unused languages, because their authors never invented any Esperanto legends".[T 16]

The popularity of Tolkien's books has had a small but lasting effect on the use of language in fantasy literature in particular, and even on mainstream dictionaries, which now commonly accept Tolkien's idiosyncratic spellings dwarves and dwarvish (alongside dwarfs and dwarfish), which had been little used since the mid-19th century and earlier. (In fact, according to Tolkien, had the Old English plural survived, it would have been dwarrows or dwerrows.) He coined the term eucatastrophe, used mainly in connection with his own work.[171]

Artwork

[edit]Tolkien learnt to paint and draw as a child and continued to do so all his adult life. From early in his writing career, the development of his stories was accompanied by drawings and paintings, especially of landscapes, and by maps of the lands in which the tales were set. He produced pictures to accompany the stories told to his own children, including those later published in Mr Bliss and Roverandom, and sent them elaborately illustrated letters purporting to come from Father Christmas. Although he regarded himself as an amateur, the publisher used the author's own cover art, his maps, and full-page illustrations for the early editions of The Hobbit. He prepared maps and illustrations for The Lord of the Rings, but the first edition contained only the maps, his calligraphy for the inscription on the One Ring, and his ink drawing of the Doors of Durin. Much of his artwork was collected and published in 1995 as a book: J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. The book discusses Tolkien's paintings, drawings, and sketches and reproduces approximately 200 examples of his work.[172] Catherine McIlwaine curated a major exhibition of Tolkien's artwork at the Bodleian Library, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, accompanied by a book of the same name that analyses Tolkien's achievement and illustrates the full range of the types of artwork that he created.[173]

Legacy

[edit]Influence

[edit]While many other authors had published works of fantasy before Tolkien, the great success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings led directly to a popular resurgence and the shaping of the modern fantasy genre. This has caused Tolkien to be popularly identified as the "father" of modern fantasy literature[174][175]—or, more precisely, of high fantasy,[176] as in the work of authors such as Ursula Le Guin and her Earthsea series.[177] In 2008 The Times ranked him sixth on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[178] His influence has extended to music, including the Danish group the Tolkien Ensemble's setting of all the poetry in The Lord of the Rings to their vocal music;[179] and to a broad range of games set in Middle-earth.[180] Among literary allusions to Tolkien, he appears as the elderly "Professor J. B. Timbermill" in all five novels in J. I. M. Stewart's series A Staircase in Surrey.[181][182] The scholar Tom Shippey describes Tolkien as the "author of the [20th] century",[183] and states that "I do not think any modern writer of epic fantasy has managed to escape the mark of Tolkien, no matter how hard many of them have tried".[184] John Clute, writing in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, similarly credits Tolkien with being "the twentieth-century's single most important author of fantasy".[185] His work has had a massive impact on western pop culture, and remains extremely influential.[186]

Adaptations

[edit]In a 1951 letter to the publisher Milton Waldman (1895–1976), Tolkien wrote about his intentions to create a "body of more or less connected legend", of which "[t]he cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama".[T 17] The hands and minds of many artists have indeed been inspired by Tolkien's legends. Personally known to him were Pauline Baynes (Tolkien's favourite illustrator of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Farmer Giles of Ham) and Donald Swann (who set the music to The Road Goes Ever On). Queen Margrethe II of Denmark created illustrations to The Lord of the Rings in the early 1970s. She sent them to Tolkien, who was struck by the similarity they bore in style to his own drawings.[187] Tolkien was not implacably opposed to the idea of a dramatic adaptation, however, and sold the film, stage and merchandise rights of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings to United Artists in 1968. United Artists never made a film, although the director John Boorman was planning a live-action film in the early 1970s. In 1976 the rights were sold to Tolkien Enterprises, a division of the Saul Zaentz Company, and the first film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings was released in 1978 as an animated rotoscoping film directed by Ralph Bakshi with screenplay by the fantasy writer Peter S. Beagle. It covered only the first half of the story of The Lord of the Rings.[188]

In 1977 an animated musical television film of The Hobbit was made by Rankin-Bass, and in 1980 they produced the animated musical television film The Return of the King, which covered some of the portions of The Lord of the Rings that Bakshi was unable to complete. From 2001 to 2003 New Line Cinema released The Lord of the Rings as a trilogy of live-action films that were filmed in New Zealand and directed by Peter Jackson. The series was successful, performing extremely well commercially and winning numerous Oscars.[189] From 2012 to 2014 Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema released The Hobbit, a series of three films based on The Hobbit, with Peter Jackson serving as executive producer, director, and co-writer.[190]

In 2017 Amazon acquired the global television rights to The Lord of the Rings, for a series of new stories set before The Fellowship of the Ring.[191][192] The television series was titled The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power; the first season was released in 2022 and the second in 2024. Also in 2024, New Line Cinema and others produced The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, an anime fantasy film directed by the Japanese director Kenji Kamiyama.

Possible sainthood

[edit]On 2 September 2017 the Oxford Oratory, Tolkien's parish church during his time in Oxford, offered its first Mass for the intention of Tolkien's cause for beatification to be opened.[193][194] A prayer was written for his cause.[193]

The religious experience of Tolkien was described by Holly Ordway in the book Tolkien's Faith: A Spiritual Biography (2023).

Memorials

[edit]Tolkien and the characters and places from his works have become eponyms of many real-world objects. These include geographical features on Titan (Saturn's largest moon),[195] street names such as There and Back Again Lane, inspired by The Hobbit,[196] mountains such as Mount Shadowfax, Mount Gandalf and Mount Aragorn in Canada,[197][198] companies such as Palantir Technologies[199] and species including the wasp Shireplitis tolkieni,[200] 37 new species of Elachista moths[200][201] and many fossils.[202][203][204]

Since 2003 The Tolkien Society has organized Tolkien Reading Day, which takes place on 25 March in schools around the world.[205] In 2013 Pembroke College, Oxford University, established an annual lecture on fantasy literature in Tolkien's honour.[206] In 2012 Tolkien was among the British cultural icons selected by the artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork—the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover—to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admired.[207][208] A 2019 biographical film, Tolkien, focused on Tolkien's early life and war experiences.[209] The Tolkien family and estate stated that they did not "approve of, authorise or participate in the making of" the film.[210]

Several blue plaques in England commemorate places associated with Tolkien, including for his childhood, his workplaces, and places he visited.[45][211][212]

| Address | Commemoration | Date unveiled | Issued by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarehole Mill, Hall Green, Birmingham | "Inspired" 1896–1900 (i.e. lived nearby) | 15 August 2002 | Birmingham Civic Society and The Tolkien Society[213] |

| 1 Duchess Place, Ladywood, Birmingham | Lived near here 1902–1910 | Unknown | Birmingham Civic Society[214] |

| 4 Highfield Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham | Lived here 1910–1911 | Unknown | Birmingham Civic Society and The Tolkien Society[215] |

| Plough and Harrow, Hagley Road, Birmingham | Stayed here June 1916 | June 1997 | The Tolkien Society[216] |

| 2 Darnley Road, West Park, Leeds | First academic appointment, Leeds | 1 October 2012 | The Tolkien Society and Leeds Civic Trust[217] |

| 20 Northmoor Road, North Oxford | Lived here 1930–1947 | 3 December 2002 | Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board[218] |

| Hotel Miramar, East Overcliff Drive, Bournemouth | Stayed here regularly from the 1950s until 1972 | 10 June 1992 by Priscilla Tolkien | Borough of Bournemouth[219] |

| St Mary Immaculate, 45 West Street, Warwick | Married here 22 March 1916 | 6 July 2018 | Warwick Town Council[220] |

The Royal Mint produced a commemorative £2 coin in 2023 to mark the 50th anniversary of Tolkien's death.[221]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tolkien pronounced his surname /ˈtɒlkiːn/.[1][page needed] In General American, the surname is commonly pronounced /ˈtoʊlkiːn/ ⓘ.[2]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #190 to Rayner Unwin, 3 July 1956: "After all the book is English, and by an Englishman"

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #267 to Michael Tolkien, 9–10 January 1965.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #306 to Michael Tolkien, 1967 or 1968

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carpenter 2023, Letters #43 to Michael Tolkien, 6–8 March 1941

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, Letters #340 to Christopher Tolkien, 11 July 1972.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #35 to C. A. Furth, Allen & Unwin, 2 February 1939 (see also editorial note).

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #336 to Sir Patrick Browne, 23 May 1972

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #332 to Michael Tolkien, 24 January 1972

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #294 to Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, 8 February 1967

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #334 to Rayner Unwin, 30 March 1972 (editorial note).

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #250 to Michael Tolkien, 1 November 1963

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #52 to Christopher Tolkien, 29 November 1943

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #7, to the Electors of the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, University of Oxford, 27 June 1925

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #163 to W. H. Auden, 7 June 1955.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #144 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April 1954.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #180 to 'Mr Thompson' (draft), 14 January 1956.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #131 to Milton Walden, late 1951

Secondary

[edit]- ^ Tolkien, Christopher, ed. (1988). The Return of the Shadow: The History of The Lord of the Rings, Part One. The History of Middle-earth. Vol. 6. ISBN 0-04-440162-0.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Brennan, David (21 September 2018). "The Hobbit: How Tolkien Sunk a German Anti-Semitic Inquiry Into His Race". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

My great-great-grandfather came to England in the eighteenth century from Germany: the main part of my descent is therefore purely English, and I am an English subject – which should be sufficient.

- ^ a b c d Derdziński, Ryszard (2017). "On J. R. R. Tolkien's Roots" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Derdziński, Ryszard. "Z Prus do Anglii. Saga rodziny J. R. R. Tolkiena (XIV–XIX wiek)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Absolute Verteilung des Namens 'Tolkien'". verwandt.de (in German). MyHeritage UK. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "Ash nazg gimbatul". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 35/1969. 25 August 1969. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011.

Professor Tolkien, der seinen Namen vom deutschen Wort 'tollkühn' ableitet,... .

- ^ Geier, Fabian (2009). J. R. R. Tolkien (in German). Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-499-50664-2.

- ^ Cawthorne, Nigel (2012). A Brief Guide to J. R. R. Tolkien: A Comprehensive Introduction to the Author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. London: Robinson. ISBN 978-1-78033-860-6.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 14

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 13. Both the spider incident and the visit to the homestead are covered here.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 24

- ^ Carpenter 1977, Ch I, "Bloemfontein". At 9 Ashfield Road, King's Heath.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 27

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 113

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 29

- ^ a b Doughan, David (2002). "JRR Tolkien Biography". Life of Tolkien. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006.

- ^ Butts, Dennis (2004). "Shaping boyhood: British Empire builders and adventurers". In Hunt, Peter (ed.). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Vol. 1 (Second ed.). Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 340–351. ISBN 0-203-32566-4.

By the 1840s, of course, adults were already reading tales of adventure involving Red Indians

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 22

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 30

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, p. 31

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 39

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 25–38

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 24–51

- ^ "Tolkien's Not-So-Secret Vice". Archived from the original on 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Tolkien's Languages". Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- ^ Bramlett, Perry C. (2002). I Am in Fact a Hobbit: An Introduction to the Life and Works of J. R. R. Tolkien. Mercer University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-86554-894-7. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ Smith, Arden R. (2006). "Esperanto". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. p. 172, and Book of the Foxrook Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine; transcription on Tolkien i Esperanto Archived 19 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine; the text begins with "PRIVATA KODO SKAŬTA" (Private Scout Code).

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 53–54

- ^ Tolkien and the Great War, p. 6.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 82

- ^ "1911 – J. R. R. Tolkien besichtigt das Oberwallis". Valais Wallis Digital (in German). Archived from the original on 5 March 2016, citing Carpenter 2023, Letters #306 to Michael Tolkien, autumn 1968.

- ^ a b Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (26 February 2004). The Lord of the Rings JRR Tolkien Author and Illustrator. Royal Mail Group plc (commemorative postage stamp pack).

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 45, 63–64

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 40

- ^ Doughan, David (2002). "War, Lost Tales and Academia". J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 43

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, pp. 67–69

- ^ Tolkien & Tolkien 1992, p. 34

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 73

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 86

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, pp. 77–85

- ^ "No. 29232". The London Gazette. 16 July 1915. p. 6968.

- ^ Tolkien and the Great War, p. 94.

- ^ a b "Memorials". The Tolkien Society. 29 October 2016. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Garth 2003, p. 138

- ^ Garth 2003, pp. 144–145

- ^ Garth 2003, pp. 147–148

- ^ Garth 2003, pp. 148–149

- ^ a b Garth 2003, p. 149

- ^ Quoted in Garth 2003, p. 200

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 93

- ^ Tolkien & Tolkien 1992, p. 40

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 93, 103, 105

- ^ Garth 2003, pp. 94–95

- ^ Garth 2003, pp. 207 et seq.

- ^ Tolkien's Webley .455 service revolver was put on display in 2006 as part of a Battle of the Somme exhibition in the Imperial War Museum, London. (See "Second Lieutenant J R R Tolkien". Battle of the Somme. Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. and "Webley.455 Mark 6 (VI Military)". Imperial War Museum Collection Search. Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018.)

- ^ Several of his service records, mostly dealing with his health problems, can be seen at the National Archives. ("Officer's service record: J R R Tolkien". First World War. National Archives. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2007.)

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 98

- ^ "No. 30588". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 March 1918. p. 3561.

- ^ Following rural English usage, Tolkien used the name "hemlock" for various plants with white flowers in umbels, resembling hemlock (Conium maculatum); the flowers Edith danced among were more probably cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) or wild carrot (Daucus carota). See John Garth, Tolkien and the Great War (Harper Collins/Houghton Mifflin 2003, chapter 12), and Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall, & Edmund Weiner, The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary (OUP 2006).

- ^ Grotta 2002, p. 58

- ^ "No. 32110". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 November 1920. p. 10711.

- ^ Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Zettersten, A. (25 April 2011). J. R. R. Tolkien's Double Worlds and Creative Process: Language and Life. Springer. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-230-11840-9. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018.

- ^ Grotta, Daniel (28 March 2001). J. R. R. Tolkien Architect of Middle Earth. Running Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-7624-0956-3. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

- ^ Shippey, T. A. (11 April 2024). "Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1892–1973)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (revised ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31766. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Memorial to JRR Tolkien commissioned". Pembroke College Oxford. University of Oxford. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ See The Name Nodens (1932) in the bibliographical listing. For the etymology, see Nodens#Etymology.

- ^ Acocella, Joan (2 June 2014). "Slaying Monsters: Tolkien's 'Beowulf'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 143

- ^ Ramey, Bill (30 March 1998). "The Unity of Beowulf: Tolkien and the Critics". Wisdom's Children. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006.

- ^ Tolkien: Finn and Hengest. Chiefly, p.4 in the Introduction by Alan Bliss.

- ^ Tolkien: Finn and Hengest, the discussion of Eotena, passim.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2001). "Tolkien and Beowulf – Warriors of Middle-earth". Amon Hen. Archived from the original on 9 May 2006.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, p. 133

- ^ Turing, Dermot (2020). The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park. London: Arcturus Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-78950-621-1.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2006). The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Vol. 2. HarperCollins. pp. 224, 226, 232. ISBN 978-0-618-39113-4.

- ^ Grotta, Daniel (28 March 2001). J. R. R. Tolkien Architect of Middle Earth. Running Press. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-7624-0956-3. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- ^ McCoy, Felicity Hayes (11 June 2019). "When my father met Gandalf: Tolkien's time as an external examiner at UCG". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded". National University of Ireland. 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 206–208

- ^ Lee 2020, pp. 12–15

- ^ "In memory of Priscilla Tolkien". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 167

- ^ "Nomination Database". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, Part 7, Chapter 2 "Bournemouth"

- ^ a b Tolkien, Simon (2003). "My Grandfather JRR Tolkien". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ "No. 45554". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1972. p. 9.

- ^ Shropshire County Council (2002). "J. R. R. Tolkien". Literary Heritage, West Midlands. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- ^ Birzer, Bradley J. (13 May 2014). J. R. R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-4976-4891-3. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b "J. R. R. Tolkien Dead at 81; Wrote 'The Lord of the Rings'". The New York Times. 3 September 1973. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2024). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Tolkien, John Ronald Reul of Merton College Oxford". probatesearchservice.gov. UK Government. 1973. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1978). The Inklings. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-00-774869-3. Lewis was brought up in the Church of Ireland.

- ^ Ware, Jim (2006). Finding God in The Hobbit. Tyndale House Publishers. p. xxii. ISBN 978-1-4143-0596-7.

- ^ Ordway 2023, p. 328

- ^ Ordway 2023, p. 328

- ^ Ordway 2023, p. 329

- ^ Ordway 2023, pp. 332–333

- ^ a b "Quotation of the day on the most improper job..." American Enterprise Institute. 23 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Nardi, Dominic J. (2014). "Political Institutions in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying About the Lack of Democracy". Mythlore. 33 (1 (125)): 101–123.

- ^ Miltimore, Jon. "What Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter Teach Us about Power". fee.org. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ Brown, Jack (20 October 2022). "The Lord of the Rings and the corrupting influence of power". Pacific Legal Foundation. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ Yatt, John (2 December 2002). "Wraiths and Race". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Rogers, William N. II; Underwood, Michael R. (2000). "Gagool and Gollum: Exemplars of Degeneration in King Solomon's Mines and The Hobbit". In Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel (eds.). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-313-30845-1. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Magoun, John F. G. (2006). "South, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 622–623. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- ^ Rearick, Anderson (2004). "Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien's World". Modern Fiction Studies. 50 (4): 866–867. doi:10.1353/mfs.2005.0008. ISSN 0026-7724. JSTOR 26286382. S2CID 162647975.

- ^ Power, Ed (27 November 2018). "JRR Tolkien's orcs are no more racist than George Lucas's Stormtroopers". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2004). "Myth, Late Roman History, and Multiculturalism in Tolkien's Middle-Earth". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: a Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 101–117. ISBN 978-0-8131-2301-1.

- ^ Lobdell, Jared (2004). The World of the Rings. Open Court. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-87548-303-0.

- ^ Bhatia, Shyam (8 January 2003). "The Lord of the Rings rooted in racism". Rediff India Abroad. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel, eds. (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Greenwood Publishing Group.[pages needed]

- ^ Saguaro, Shelley; Thacker, Deborah Cogan (2013). "Tolkien and Trees" (PDF). In Hunt, Peter (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien: New Casebook. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-26399-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2016.

- ^ Dickerson, Matthew; Evans, Jonathan (2006). Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of J. R. R. Tolkien. University of Kentucky Press. ISBN 978-0-8131-2418-6.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 48–49 and throughout

- ^ Bofetti, Jason (November 2001). "Tolkien's Catholic Imagination". Crisis Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006.

- ^ Caldecott, Stratford (January–February 2002). "The Lord & Lady of the Rings". Touchstone Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011.

- ^ Yolen, Jane (1992). "Introduction". In Greenberg, Martin H. (ed.). After the King: Stories in Honor of J. R. R. Tolkien. Macmillan. pp. vii–viii. ISBN 0-312-85175-8.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 40–41

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 104, 190–197, 217 and throughout

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 66–74 and throughout

- ^ Fimi, Dimitra (2006). "'Mad' Elves and 'elusive beauty': some Celtic strands of Tolkien's mythology". Folklore. 117 (2): 156–170. doi:10.1080/00155870600707847. ISSN 1547-3155. JSTOR 30035484. S2CID 162292626.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (1 March 2004). "Lord of the Rings Inspired by an Ancient Epic". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 16 March 2006.

- ^ Purtill, Richard L. (2003). J. R. R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion. San Francisco: Harper & Row. pp. 52, 131. ISBN 0-89870-948-2.

- ^ Flieger, Verlyn (2001). "Strange Powers of the Mind". A Question of Time: J. R. R. Tolkien's Road to Faërie. Kent State University Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-87338-699-9. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 77

- ^ Morton, Andrew (2009). Tolkien's Bag End. Studley, Warwickshire: Brewin Books. ISBN 978-1-85858-455-3. OCLC 551485018. Morton wrote an account of his findings. Archived 5 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine for the Tolkien Library.

- ^ Resnick, Henry (1967). "An Interview with Tolkien". Niekas. pp. 37–47.

- ^ Lobdell, Jared C. (2004). The World of the Rings: Language, Religion, and Adventure in Tolkien. Open Court. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-8126-9569-4.

- ^ Rogers, William N. II; Underwood, Michael R. (2000). "Gagool and Gollum: Exemplars of Degeneration in King Solomon's Mines and The Hobbit". In Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel (eds.). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Greenwood Press. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-313-30845-1.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 180

- ^ Ciabattari, Jane (20 November 2014). "Hobbits and hippies: Tolkien and the counterculture". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Niles, John D. (1998). "Beowulf, Truth, and Meaning". In Bjork, Robert E.; Niles, John D. (eds.). A Beowulf Handbook. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-8032-6150-0.

Bypassing earlier scholarship, critics of the past fifty years have generally traced the current era of Beowulf studies back to 1936 [and Tolkien's essay].

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 66–74

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 56–57

- ^ Phillip, Norman (2005). "The Prevalence of Hobbits". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ "Grand Tours: Who Travels the World in a Single Night?". The Independent on Sunday. 22 December 2002. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Artamonova, Maria (15 April 2014). "'Minor' Works". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. Wiley. Chapter 13. doi:10.1002/9781118517468. ISBN 978-0-470-65982-3. S2CID 160570361.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Anderson, Douglas A. (1993). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Books. ISBN 0-938768-42-5.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, pp. 187–208

- ^ "Oxford Calling". The New York Times. 5 June 1955. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ Fimi, Dimitra (2020) [2014]. "Later Fantasy Fiction: Tolkien's Legacy". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 335–349. ISBN 978-1-119-65602-9.

- ^ Seiler, Andy (16 December 2003). "'Rings' comes full circle". USA Today. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Cooper, Callista (5 December 2005). "Epic trilogy tops favorite film poll". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006.

- ^ O'Hehir, Andrew (4 June 2001). "The book of the century". Salon. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006.

- ^ Diver, Krysia (5 October 2004). "A lord for Germany". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 17 August 2007.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G. (1993). J.R.R. Tolkien: a descriptive bibliography. Douglas A. Anderson. Winchester: Oak Knoll Books. ISBN 1-873040-11-3. OCLC 27013976.

- ^ Nagy, Gergely (2020) [2014]. "'The Silmarillion': Tolkien's Theory of Myth, Text, and Culture". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 107–118. ISBN 978-1-119-65602-9.

- ^ "1978 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009.

- ^ Martinez, Michael (27 July 2002). "Middle-earth Revised, Again". Michael Martinez Tolkien Essays. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008.

- ^ Grovier, Kelly (27 April 2007). "In the name of the father". The Observer. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Allen, Katie (6 January 2009). "New Tolkien for HarperCollins". The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Flood, Alison (9 October 2012). "New JRR Tolkien epic due out next year". guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ "JRR Tolkien's Beowulf translation to be published". BBC News. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary". Publishers Weekly. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014.

- ^ Flood, Alison (12 August 2015). "JRR Tolkien's first fantasy story to be published this month". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ Flood, Alison (19 October 2016). "JRR Tolkien's Middle-earth love story to be published next year". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016.

- ^ Helen, Daniel (30 August 2018). "The Fall of Gondolin published". Tolkien Society. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019.

- ^ Flood, Alison (10 April 2018). "The Fall of Gondolin, 'new' JRR Tolkien book, to be published in 2018". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018.

- ^ "J. R. R. Tolkien Collection". Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University. 4 March 2003. Archived from the original on 12 January 1998.

- ^ McDowell, Edwin (4 September 1983). "Middle-earth Revisited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ Turley, Katherine (2 June 2018). "Inside a Very Great Story...". The Tablet. pp. 20–21.

- ^ "Beebe discovers unpublished C. S. Lewis manuscript". txstate.edu, University News Service. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (2003). The meaning of everything: the story of the Oxford English dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860702-4. OCLC 52830480.

- ^ Gilliver, Peter (2006). The ring of words: Tolkien and the Oxford English dictionary. Jeremy Marshall, E. S. C. Weiner. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861069-4. OCLC 65197968.

- ^ Grotta, Daniel (1976). J.R.R. Tolkien: architect of Middle Earth. Frank Wilson. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 0-914294-29-6. OCLC 1991974.

- ^ Scull, Christina (2006). The J.R.R. Tolkien companion & guide. Wayne G. Hammond. Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 249. ISBN 0-261-10381-4. OCLC 82367707.

- ^ Corsetti, Renato (31 January 2018). "Tolkien's 'Secret Vice'". British Library. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018.

- ^ Fisher, Richard (2022). "Eucatastrophe: Tolkien's word for the "anti-doomsday"". BBC. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 7, 9, and whole book. ISBN 978-0-395-74816-9. OCLC 33450124.

- ^ McIlwaine, Catherine (2018). Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth. Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-1-85124-485-0.

- ^ Mitchell, Christopher. "J. R. R. Tolkien: Father of Modern Fantasy Literature". Veritas Forum. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009.