Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boustrophedon

View on Wikipedia

Boustrophedon (/ˌbuːstrəˈfiːdən/ BOO-strə-FEE-dən[1]) is a style of writing in which alternate lines of writing are reversed, with letters also written in reverse, mirror-style. This is in contrast to modern European languages, where lines always begin on the same side, usually the left.

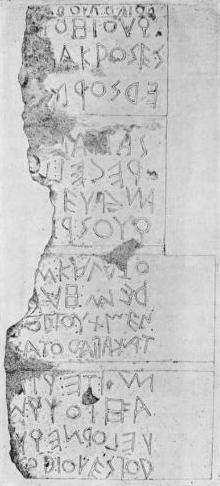

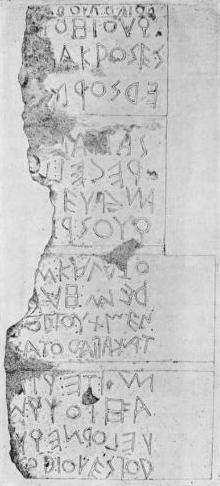

The original term comes from Ancient Greek: βουστροφηδόν boustrophēdón, a composite of βοῦς boûs, "ox"; στροφή strophḗ, "turn"; and the adverbial suffix -δόν -dón, "like, in the manner of"—that is, "like the ox turns [while plowing]".[2] It is mostly seen in ancient manuscripts and other inscriptions. It was a common way of writing on stone in ancient Greece,[3] becoming less and less popular throughout the Hellenistic period. Many ancient scripts, such as Etruscan, Safaitic, and Sabaean, were frequently or even typically written boustrophedon.

Reverse boustrophedon

[edit]

The wooden boards and other incised artefacts of Rapa Nui bear a boustrophedonic script called Rongorongo, which remains undeciphered. In Rongorongo, the text in alternate lines was rotated 180 degrees rather than mirrored; this is termed reverse boustrophedon.[4]

The reader begins at the bottom left-hand corner of a tablet, reads a line from left to right, then rotates the tablet 180 degrees to continue on the next line from left to right again. When reading one line, the lines above and below it appear upside down. The writing continues onto the second side of the tablet at the point where it finishes off the first, so if the first side has an odd number of lines, the second will start at the upper left-hand corner, and the direction of writing shifts to top to bottom. Larger tablets and staves may have been read without turning if readers could read upside-down.

The Hungarian folklorist Sebestyén Gyula writes that ancient boustrophedon writing resembles the Hungarian rovás-sticks of Old Hungarian script made by shepherds. A notcher would hold the wooden stick in their left hand, cutting the letters with their right hand from right to left. When the first side was complete, they would flip the stick over vertically and start to notch the opposite side in the same manner. When unfolded horizontally (as in the case of the stone-cut boustrophedon inscriptions), the result is writing that starts from right to left and continues from left to right in the next row, with letters turned upside down. Sebestyén suggests that the ancient boustrophedon writings were copied from such wooden sticks with cut letters, applied for epigraphic inscriptions (not recognizing the real meaning of the original wooden type).[5]

Example of Hieroglyphic Luwian

[edit]The Luwian language had a version, Hieroglyphic Luwian, that is read in boustrophedon[6] style (most of the language was written down in cuneiform).

Hieroglyphic Luwian is read boustrophedonically, with the direction of any individual line pointing into the front[ambiguous] of the animals or body parts constituting certain hieroglyphs. While Egyptian hieroglyphs' numerous ideograms and logograms show directionality, the lineal direction of the text in hieroglyphic Luwian is harder to see.

Other examples and modern use

[edit]A modern example of boustrophedonics is the numbering scheme of sections within survey townships in the United States and Canada. In both countries, survey townships are divided into a 6-by-6 grid of 36 sections. In the U.S. Public Land Survey System, Section 1 of a township is in the northeast corner, and the numbering proceeds boustrophedonically until Section 36 is reached in the southeast corner.[7] Canada's Dominion Land Survey also uses boustrophedonic numbering, but starts at the southeast corner.[8] Following a similar scheme, street numbering in the United Kingdom sometimes proceeds serially in one direction then turns back in the other (the same numbering method is used in some mainland European cities). This is in contrast to the more common method of odd and even numbers on opposite sides of the street both increasing in the same direction.

The Avoiuli script used on Pentecost Island in Vanuatu is written boustrophedonically by design.

The Indus script, though still undeciphered, can be written boustrophedonically.[9]

Another example is the boustrophedon transform, known in mathematics.[10]

Sources also indicate that Linear A may have been written left-to-right, right-to-left, and in boustrophedon fashion.[11]

Permanent human teeth are numbered in a boustrophedonic sequence in the American Universal Numbering System.

Marilyn Aronberg Lavin adopted the term to describe a type of narrative direction a mural painting cycle may take:“The boustrophedon is found on the surface of single walls [linear] as well on one or more opposing walls [aerial] of a given sanctuary. The narrative reads on several tiers, first from left to right, then reversing from right to left, or vice versa.”[12]

In digital file compression for spatial data, the GRIB2 compression algorithm packs values “boustrophedonically to make ‘consecutive’ values more redundant.”[13]

Moon type, an early form of notation for the visually impaired, was sometimes written in boustrophedon so that the reader would not need to lift their finger from the reading surface after reaching the end of a line. While the reading direction changed, the orientation of the glyphs remained constant in relation to the page.[14]

In 1884 the British printer and publisher Andrew White Tuer published Are We to Read Backwards?, written by James Millington, for the Leadenhall Press, in which the principle was tested on one page of English text.[15] In 2025 the graphic and type designer Carl J. Kurtz expanded on the thoughts in Are We to Read Backwards?, developing a Latin typeface to accommodate boustrophedon and setting a book, written in English, in boustrophedon to test its feasibility for modern texts.[16]

In constructed languages

[edit]The constructed language Ithkuil uses a boustrophedon script.

The Atlantean language created by Marc Okrand for Disney's 2001 film Atlantis: The Lost Empire is written in boustrophedon to recreate the feeling of flowing water.

The code language used in The Montmaray Journals, Kernetin, is written boustrophedonically. It is a combination of Cornish and Latin and is used for secret communication.[17]

J. R. R. Tolkien wrote that many elves were ambidextrous and would write left-to-right or right-to-left as needed.[18]

In the Green Star novels by Lin Carter, the script of the Laonese people is written in boustrophedon style.[19]

Rousseau

[edit]To make it easier to read from one musical staff to another, and avoid "jumping the eye", Jean-Jacques Rousseau envisioned a "boustrophedon" notation. This requires the writer to write the second staff from right to left, then the next one from left to right, etc. The words are reversed in every other line.[20]

See also

[edit]- Ambigram

- Mirror writing

- Sator Square is read boustrophedonically in one interpretation

- Stoichedon

References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "boustrophedon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ βοῦς, στροφή, βουστροφηδόν. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Threatte, Leslie (1980). The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions. Vol. I Phonology. W. de Gruyter. pp. 54–55. ISBN 3-11-007344-7.

- ^ Smithfield, Brad (September 7, 2016). "Rongorongo-Hieroglyphs written with shark teeth from Easter Island, remain indecipherable". The Vintage News.

- ^ Sebestyén, Gyula (1915). A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei. Budapest. pp. 22, 137–138, 160. ISBN 9786155242106.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Campbell, George Frederick (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 0-415-20296-5.

- ^ Stilgoe, John R. (1982). Common Landscape of America, 1580 to 1845. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0300030464.

- ^ Taylor, W.A. (2004) [1975]. Crown Lands: A History of Survey Systems (PDF) (5th Reprint ed.). Victoria, British Columbia: Registries and Titles Department, Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management. p. 21.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2003). "The Indus Civilization: An introduction to environment, subsistence, and cultural history". In Weber, Steven A.; Belcher, William R. (eds.). Indus ethnobiology: New perspectives from the field. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (2002). CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics (Second ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. p. 273. ISBN 1-58488-347-2.

- ^ Salgarella, Ester (2022). "Linear A". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8927 (inactive 16 July 2025).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Lavin, Marilyn Aronberg (1990). The Place of Narrative. Mural Decoration in Italian Churches, 431–1600. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-226-46956-5.

- ^ Glahn, Harry R. (2002). "GRIB2 the WMO Standard for Gridded Data" (PDF). National Weather Service.

- ^ "In Regard to Moon". www.unicode.org. Retrieved 2025-12-03.

- ^ Millington, James (1884). Are we to Read Backwards. London: Field & Tuer. p. 56.

- ^ "Instagram". www.instagram.com. Retrieved 2025-12-03.

- ^ Cooper, Michelle (2008). A Brief History of Montmaray. Australia: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-0375858642.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2021). The nature of Middle-earth : late writings on the lands, inhabitants, and metaphysics of Middle-earth. Carl F. Hostetter (First U.S. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-358-45460-1. OCLC 1224246902.

- ^ Carter, Lin (1972). Under the Green Star. DAW Books. p. 47. ISBN 9780879974336.

- ^ "Rousseau, Happy at Chenonceau". Google Arts & Culture.

External links

[edit]Boustrophedon

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Definition

Boustrophedon is a bidirectional writing style employed in certain ancient scripts, in which successive lines of text are inscribed in alternating directions, typically progressing from left to right on the first line and from right to left on the second, with this pattern repeating throughout the text.[3] In this system, the characters within each line are generally oriented to face the direction of reading, meaning that letters or symbols on right-to-left lines are often mirrored or rotated relative to those on left-to-right lines to maintain visual consistency for the reader. The term derives from an analogy to the path of an ox plowing a field, where the animal moves forward in one direction across a row before turning at the end to traverse the next row in the opposite direction, thereby evoking the back-and-forth motion of the writing.[3] This method contrasts with unidirectional scripts, such as the modern Latin alphabet, which consistently flow in a single direction (left to right), and with consistently right-to-left systems like Arabic, where all lines maintain the same orientation without alternation.[4] Visually, boustrophedon text resembles a serpentine progression: the first line might read "ABCDE" from left to right with standard letter forms, while the second line reads "EDCBA" from right to left, with each letter mirrored (e.g., a standard "A" becomes its horizontal flip) to align with the reading path, ensuring that the overall inscription appears balanced and readable when viewed from the appropriate side. This technique facilitated efficient use of space on surfaces like stone or clay tablets in early writing practices.[3]Etymology

The term boustrophedon derives from the Ancient Greek adverb βουστροφηδόν (boustrophēdón), a compound word formed from βοῦς (boûs, meaning "ox") and στροφή (strophḗ, meaning "turn" or "turning"), combined with the adverbial suffix -δόν (-dón), yielding a literal translation of "ox-turning" or "as the ox turns."[5][6][7] This etymology evokes the alternating path of an ox plowing a field, turning at each end to traverse back in the opposite direction.[8] Although the adverb βουστροφηδόν appears in classical Greek texts to describe plowing or similar motions, its application as a technical term for the bidirectional writing style emerged in European scholarship during the late 18th century, initially to characterize ancient Greek inscriptions.[5][9] In contemporary linguistics and epigraphy, the term has broadened beyond its Greek origins to denote analogous bidirectional systems in other ancient scripts, including those of the Etruscans, early Romans, and certain Near Eastern traditions, facilitating cross-cultural analysis of writing directions.[8][10]Historical Usage

Origins in Ancient Writing Systems

The earliest known instances of boustrophedon writing appear in the scripts of Bronze Age Crete during the 2nd millennium BCE, particularly in the later phases of Cretan hieroglyphic and Linear A systems used by the Minoan civilization. Cretan hieroglyphic, dating to approximately 2100–1700 BCE, and Linear A, from around 1800–1450 BCE, occasionally employed this alternating direction to inscribe signs on clay tablets, seals, and other media, potentially linking back to earlier proto-writing practices that emphasized practical arrangement over strict linearity. These examples represent foundational developments in Aegean writing, where boustrophedon facilitated compact recording in administrative and ritual contexts without standardized directional norms.[1] Around the same period, boustrophedon emerged in West Semitic scripts, notably in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions from sites like Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula and Wadi el-Hol in Egypt, dated to circa 1800–1500 BCE. These early alphabetic texts, carved by Semitic-speaking workers, adapted the style possibly to enhance efficiency in stone engraving, allowing continuous inscription across surfaces by alternating line directions and mirroring signs, which minimized repositioning of the tool or body. This innovation marked a shift toward phonetic writing in the Levant and eastern Mediterranean, influencing subsequent Semitic-derived systems.[11] By the Iron Age (ca. 1200–500 BCE), boustrophedon saw broader adoption across Mediterranean cultures, particularly in early Greek alphabetic inscriptions on durable surfaces like stone and pottery. The style proved practical for engravers and scribes, enabling fluid inscription without repositioning, thus optimizing space on limited areas and adapting to diverse media from durable stone to later perishable materials, before directional uniformity became prevalent.[12]Adoption in Specific Civilizations

Boustrophedon writing was prominently adopted in ancient Greek inscriptions starting from the 8th century BCE, as seen in the Dipylon Oinochoe from Athens (ca. 740 BCE), particularly in archaic Attic and Ionic dialects, where it appeared frequently on stone monuments such as dedications and decrees.[13] This practice facilitated efficient use of space on durable surfaces, with examples including sacral inscriptions from the Athenian Agora dated to the late 6th or early 5th century BCE, reflecting its role in public and religious epigraphy.[13] In these dialects, the alternating direction mirrored the influence of earlier Semitic scripts while adapting to Greek phonetic needs, often employing early alphabetic forms.[14] The technique also found adoption in Etruscan script from the 8th to 1st century BCE, where it appeared in various inscriptions on artifacts like vases and tombstones, demonstrating regional adaptation of alphabetic writing derived from Greek influences.[15] Early Etruscan texts occasionally employed boustrophedon to optimize inscription on irregular surfaces, contributing to the script's evolution before standardization. This usage influenced subsequent developments in Italic writing systems. In early Latin scripts prior to the 3rd century BCE, boustrophedon was employed in key epigraphic examples, such as the Forum inscription from Rome around 600–550 BCE, which alternated directions irregularly across lines, marking one of the oldest Latin texts and highlighting its transitional role in Roman epigraphy.[16] This practice, inherited via Etruscan intermediaries, persisted in monumental inscriptions before the shift to uniform left-to-right writing solidified Roman conventions. Among Anatolian languages, boustrophedon appeared in Lydian inscriptions during the archaic period (circa 7th–6th century BCE), with one documented example alternating directions on a stele, contrasting the script's predominant right-to-left orientation and illustrating experimental adaptations in western Anatolia.[17] Similarly, Phrygian texts from the 8th to 6th century BCE, such as those from Gordion, frequently used boustrophedon on rock facades and pottery, with at least 18 known instances reflecting variable directions that accommodated the language's Indo-European phonology on diverse media.[18] These applications underscore regional flexibility in Anatolian epigraphy. Presence of boustrophedon in Semitic scripts was rare after early proto-alphabetic stages, with debated examples in transitional Phoenician texts like the Nora stone (late 9th century BCE). In Old Aramaic, bidirectional shifts occasionally appear in multicultural contexts, such as inscriptions from Zincirli, influenced by interactions but not as a standard convention. By the Hellenistic period (from the 4th century BCE onward), boustrophedon declined sharply across these civilizations, largely replaced by consistent left-to-right conventions driven by the standardization of writing on papyrus rolls, which favored unidirectional flow for easier unrolling and reading in literary and administrative contexts.[19] This shift, accelerated by the spread of the Alexandrian scholarly tradition, rendered the alternating style obsolete for most practical uses, confining it to archaic monumental remnants.[12]Variations

Standard Boustrophedon

One form of boustrophedon, often described in modern contexts, follows a serpentine writing pattern in which odd-numbered lines are inscribed from left to right, while even-numbered lines proceed from right to left, mimicking the turning path of an ox plowing a field.[20] In this form, characters on the right-to-left lines are typically reversed—horizontally mirrored—such that they continue to face the direction of writing, ensuring legibility without requiring the reader to mentally flip the forms.[21] This mirroring distinguishes it from variants like reverse boustrophedon, where entire lines are rotated 180 degrees without mirroring, as seen in the undeciphered Rongorongo script of Easter Island.[6] For non-alphabetic scripts, such as logographic systems, the rules adapt to maintain orientation toward the reading flow; symbols, including those depicting figures or animals, are adjusted to face the start of each line's direction, preserving visual consistency across the alternating paths.[22] This approach ensures that iconic elements align with the script's bidirectional progression, avoiding disorientation in complex sign systems. In modern digital implementations, boustrophedon lacks dedicated Unicode support for automatic line alternation, but bidirectional text mechanisms can approximate it using control characters like the Right-to-Left Mark (U+200F), which overrides directionality for segments of text to simulate the serpentine effect in rendering engines.[23] These tools, part of the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm, facilitate mixed left-to-right and right-to-left layouts but require manual application per line for full boustrophedon emulation.[20] A key practical advantage in ancient contexts was enabling continuous writing without lifting the stylus or repositioning the writing surface, such as a wax tablet or clay medium, thereby streamlining the inscription process and reducing interruptions during extended composition.[21]Right-to-Left Starting and Unmirrored Forms

Early boustrophedon, particularly in Greek inscriptions, often began with the first line proceeding from right to left, with subsequent lines alternating to left to right, aligning with the right-to-left orientation prevalent in Semitic scripts that influenced its adoption. This configuration, sometimes termed retrograde boustrophedon due to the initial right-to-left (retrograde) direction, was common in early Greek writing, as noted by linguist Barry B. Powell in his analysis of alphabetic origins.[2] A variant maintains alternating line directions but does not mirror the letters on right-to-left lines, requiring readers to interpret those lines backward without visual adjustment to the characters. Such unmirrored forms coexisted with standard boustrophedon in certain ancient Greek inscriptions before the standardization to consistent left-to-right (orthograde) writing around the 7th to 6th centuries BCE.[24][14] Hybrid forms of these variants emerge in transitional scripts, blending directional alternations with partial reversals. For example, early Ogham inscriptions in Ireland occasionally employ boustrophedon arrangements along stone edges, combining vertical strokes with mixed reading directions. Similarly, Runic inscriptions, such as the Tune stone from Norway (circa 400 CE), utilize boustrophedon layouts, while others like the Kylver stone (5th century CE) incorporate reverse runes—mirrored individual characters—alongside standard forms, creating irregular orientations.[25][26] These variations likely stemmed from cultural and scribal preferences, particularly the entrenched right-to-left convention in Semitic writing traditions, which encouraged starting lines from the right to facilitate continuity in multicultural or borrowed script environments.[2]Notable Examples

Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions

Hieroglyphic Luwian, used from the 14th to the 7th century BCE, represents an indigenous Anatolian hieroglyphic script primarily employed for monumental inscriptions on stone, such as stelae, rock faces, and orthostats, to record the Luwian language in public and commemorative contexts.[27] This script adopted a boustrophedon writing direction, alternating between right-to-left and left-to-right lines, with non-symmetrical signs oriented to face the direction of reading within each line, facilitating a continuous flow that mimicked the turning of an ox plowing a field.[28] Words were typically formed by vertically stacked signs arranged along horizontal lines, blending syllabograms for phonetic values and logograms for semantic content, which distinguished it from alphabetic systems.[29] A prominent example is the Yalburt inscription, dated to approximately 1250 BCE during the reign of the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV (ca. 1239–1209 BCE), discovered in 1970 near Konya, Turkey, at a spring monument surrounded by a rectangular enclosure of limestone blocks.[30] This lengthy text, one of the longest known Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions, spans multiple lines in boustrophedon style, with the first line reading right-to-left and subsequent lines alternating directions, while individual hieroglyphs—depicting animals, body parts, or abstract forms—consistently face forward into the reading path to maintain visual coherence.[31] The inscription commemorates military campaigns and dedications, providing insight into Late Bronze Age Anatolian administration and religious practices. The script's inscriptions hold significant value in Indo-European linguistics, as Luwian belongs to the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family, offering some of the earliest attested evidence of this linguistic group alongside Hittite, with features like verbal conjugations and nominal declensions that illuminate proto-Indo-European reconstructions.[32] By preserving phonetic and morphological data from the 2nd millennium BCE, these texts contribute to understanding the divergence of Anatolian languages from other Indo-European branches. Transcription of Hieroglyphic Luwian poses challenges due to its boustrophedon arrangement, which requires careful tracking of directional shifts and sign orientations to avoid misaligning vertical sign groups across lines, compounded by the script's non-alphabetic nature that mixes over 500 signs in syllabic, logographic, and determinative functions, often without clear phonetic complements.[28] This variability leads to ambiguities in interpreting word boundaries and semantic intent, necessitating cross-referencing with cuneiform Luwian parallels for verification.[33]Other Ancient and Classical Examples

In ancient Greece, boustrophedon writing appeared in early coin legends from the fifth century BCE, including examples from cities such as Kyme in Aeolis, Metapontion in Magna Graecia, Rhegion in Sicily, Acragas in Sicily, and various Thessalian mints like Pharsalos and Trikka.[34] These inscriptions reflect the transitional use of the script in numismatic contexts before standardization to left-to-right directionality. Among Etruscan texts, boustrophedon was employed in archaic inscriptions, notably the Tabula Capuana, a ritual calendar tablet from the fifth century BCE discovered near Capua, which features a quasi-boustrophedon arrangement influenced by southern Etruscan traditions.[35] This style, sometimes described as "false boustrophedon," alternates directions but maintains consistent letter orientation, distinguishing it from strict forms seen in neighboring scripts.[36] Early Latin inscriptions also utilized boustrophedon, as evidenced by the Lapis Niger (Forum inscription) from the sixth century BCE, one of the oldest known Latin texts, where lines alternate directions irregularly across the monument's panels.[37] Similar patterns occur in other Republican-era artifacts, such as the Duenos inscription on a vase from the late seventh or early sixth century BCE, illustrating the script's adaptation from Etruscan influences before shifting to uniform left-to-right writing by the fourth century BCE.[38] In the ancient Near East and Arabia, Safaitic inscriptions—graffiti from nomadic tribes in the Syrian and Jordanian deserts dating from the first century BCE to the fourth century CE—frequently adopted boustrophedon, alongside vertical, circular, or spiral arrangements, as seen in examples from Wadi Sham and the northeastern Jordanian Badia. These texts, often personal or commemorative, demonstrate the script's flexibility in informal rock carvings.[39] By the Hellenistic and later classical periods, boustrophedon declined across these scripts, giving way to consistent left-to-right or right-to-left conventions for greater readability and standardization, though remnants persisted in marginalia, unofficial graffiti, and peripheral traditions into the early centuries CE.[40] This shift aligned writing more closely with spoken rhythms and facilitated the spread of alphabetic systems.[2]Modern and Constructed Applications

Use in Constructed Languages

In constructed languages, boustrophedon writing has been incorporated experimentally to evoke ancient aesthetics, enhance visual flow, and support non-linear or artistic text layouts. This approach draws inspiration from historical precedents in ancient scripts, allowing creators to blend tradition with innovation in language design.[41] A prominent example is Ithkuil, a philosophical constructed language developed by John Quijada starting in the 1970s. Its native script, Içtaîl, employs horizontal boustrophedon, with odd-numbered lines written left-to-right and even-numbered lines right-to-left; characters retain normal orientation, with even lines marked by a left-pointing arrow. This design facilitates dense morphological encoding while mimicking archaic writing systems, aiding readability in complex, idea-dense texts.[41] Similarly, the Atlantean language, invented by linguist Marc Okrand for Disney's 2001 film Atlantis: The Lost Empire, uses boustrophedon in its alphabet to convey an ancient, lost civilization's script. Lines alternate direction—left-to-right for odd lines and right-to-left for even ones—emphasizing stylistic authenticity over practical modern use.[42] In conscript communities, boustrophedon appears in projects like the Tapissary script, created by Steven Travis. This hieroglyphic conscript, inspired by American Sign Language, Chinese, Ancient Egyptian, and Mayan scripts, writes in boustrophedon to support over 7,000 cellographs and hundreds of syllabic glyphs, promoting a fluid, plow-like progression that enhances artistic expression in non-linear formats such as collages or circular compositions. Such applications highlight boustrophedon's benefits in conlang design, including reduced eye fatigue during reading and greater flexibility for visual or poetic experimentation.[43]Rousseau's Philosophical Application

Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed the use of boustrophedon in musical notation as a means to align reading with the natural movement of the eye, thereby reducing fatigue during performance or study. In his Dictionnaire de musique (1768), Rousseau described a system where alternate musical staffs would be written in opposite directions—the second from right to left, the third from left to right, and so on—to avoid the disruptive "jump" of the eye back to the beginning of the next line after completing one.[44] This innovation reflected his philosophical commitment to natural processes in the arts, drawing on observations of how the eye scans landscapes in a zigzag pattern, much like an ox plowing a field.[45] Rousseau's rationale extended his broader educational philosophy, as articulated in Emile, or On Education (1762), where he emphasized training the senses and mind through intuitive, fatigue-free methods to foster genuine learning rather than imposing rigid conventions. By applying boustrophedon to music, he sought to reform notation as a tool for more organic engagement, countering the artificiality of traditional left-to-right linearity that he viewed as contrary to human physiology.[46] Though the proposal saw limited practical adoption in musical pedagogy,[44]References

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Conlang/Intermediate/Writing

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Boustrophedon