Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

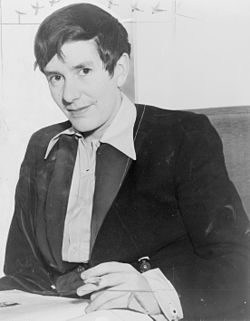

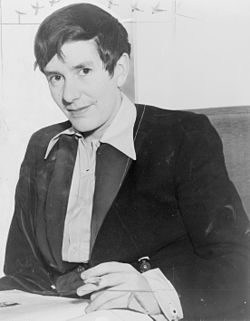

Erika Mann

View on Wikipedia

Erika Julia Hedwig Mann (9 November 1905 – 27 August 1969) was a German actress and writer, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann.

Key Information

Erika lived a bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and became a critic of National Socialism. After Hitler came to power in 1933, she moved to Switzerland, and married the poet W. H. Auden, purely to obtain a British passport and so avoid becoming stateless when the Germans cancelled her citizenship. She continued to attack Nazism, most notably with her 1938 book School for Barbarians, a critique of the Nazi education system.

During World War II, Mann worked for the BBC and became a war correspondent attached to the Allied forces after D-Day. She attended the Nuremberg trials before moving to America to support her exiled parents. Her criticisms of American foreign policy led to her being considered for deportation. After her parents moved to Switzerland in 1952, she also settled there. She wrote a biography of her father and died in Zürich in 1969.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Erika Mann was born in Munich, the first-born daughter of German writer and later Nobel Prize winner Thomas Mann and his wife, Katia (née Pringsheim), the daughter of an intellectual German family of Jewish heritage.[1][2] Due to her being the granddaughter of Júlia da Silva Bruhns, she was also of Portuguese-Indigenous Brazilian partial descent.[3] She was named after Katia Mann's brother Erik, who died early, Thomas Mann's sister Julia and her great-grandmother Hedwig Dohm. She was baptized Protestant, just as her mother had been. Thomas Mann expressed in a letter to his brother Heinrich Mann his disappointment about the birth of his first child:

It is a girl; a disappointment for me, as I want to admit between us, because I had greatly desired a son and will not stop doing so.... I feel a son is much more full of poetry [poesievoller], more than a sequel and restart for myself under new circumstances.[4]

Nevertheless, he later candidly confessed in the notes of his diary, that he "preferred, of the six, the two oldest [Erika and Klaus] and little Elisabeth with a strange decisiveness".[5]

In Erika he had a particular trust, which later showed itself when she exercised great influence on her father's important decisions.[6] Her particular role was also known by her siblings, as her brother Golo Mann remembered: "Little Erika must salt the soup".[7] This reference to the twelve-year-old Erika from the year 1917 was an often-used phrase in the Mann family.

After Erika's birth came that of her brother Klaus, with whom she was personally close her entire life. They went about "like twins" and Klaus described their closeness as follows: "our solidarity was absolute and without reservation".[8] Eventually there were four more children in total, including Golo, Monika, Elisabeth and Michael. The children grew up in Munich. On their mother's side the family belonged to the influential urban upper class and their father came from a commercial family from Lübeck and already had published the successful novel Buddenbrooks in 1901. The Mann home was a gathering-place for intellectuals and artists and Erika was hired for her first theater engagement before finishing her Abitur at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin.

Education and early theatrical work

[edit]In 1914, the Mann family obtained a villa on 1 Poschingerstraße in Bogenhausen, which in the family would come to be known as "Poschi." From 1912 to 1914, Erika Mann attended a private school with her brother, joining for a year the Bogenhausener Volksschule, and from 1915 to 1920 she attended the Höhere Mädchenschule am St. Annaplatz. In May 1921, she transferred to the Munich-based Luisengymnasium. Together with her brother Klaus, she befriended children in the neighborhood, including Bruno Walter's daughters, Gretel and Lotte Walter, as well as Ricki Hallgarten, the son of a Jewish intellectual family.

Erika Mann founded an ambitious theater troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker. While still a student at the Munich Luisengymnasium, Max Reinhardt engaged her to appear on the stage of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin for the first time. The partially mischievous pranks that she undertook in the so-called "Herzogpark-Bande" ("Herzogpark gang") with Klaus and her friends prompted her parents to send both her and Klaus to a progressive residential school, the Bergschule Hochwaldhausen, located in Vogelsberg in Oberhessen. This period in Erika Mann's schooling lasted from April to July 1922; subsequently she returned to the Luisengymnasium. In 1924 she passed the Abitur, albeit with poor marks, and began her theatrical studies in Berlin that were again interrupted, because of her numerous engagements in Hamburg, Munich, Berlin and elsewhere.

1920s and 1930s

[edit]In 1924, Erika Mann began theater studies in Berlin and acted there and in Bremen. In 1925, she played in the première of her brother Klaus's play Anja und Esther. The play, about a group of four friends who were in love with each other, opened in October 1925 to considerable publicity. In 1924 the actor Gustaf Gründgens had offered to direct the production and play one of the lead male roles, alongside Klaus, with Erika and Pamela Wedekind as the female leads. During the year they worked on the play together, Klaus was engaged to Wedekind and Erika became engaged to Gründgens. Erika and Pamela were also in a relationship together, as were, for a time, Klaus and Gustaf. For their honeymoon, in July 1926, Erika and Gründgens stayed in a hotel that Erika and Wedekind had used as a couple shortly before, with the latter checking in dressed as a man.[9] Erika's marriage to Gründgens was short-lived and they were soon living apart before divorcing in 1929.

In 1936, her brother Klaus wrote the book Mephisto, whose main character was loosely based on Gründgens, posed as a man who sold his soul to the devil, (the Nazis). The book, which drew a lawsuit from Gründgens' nephew in the 1960s, was made into a film of the same name in 1981, starring Klaus Maria Brandauer.

Erika Mann would later have relationships with Therese Giehse, Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Betty Knox, with whom she served as a war correspondent during World War II.[10]

In 1927, Erika and Klaus undertook a trip around the world,[1] which they documented in their book Rundherum; Das Abenteuer einer Weltreise. The following year, she became active in journalism and politics. She was involved as an actor in the 1931 film about lesbianism, Mädchen in Uniform, directed by Leontine Sagan, but left the production before its completion. In 1932 she published Stoffel fliegt übers Meer, the first of seven children's books.

In 1932, Erika Mann was denounced by the Brownshirts after she read a pacifist poem to an anti-war meeting. She was fired from an acting role after the theatre concerned was threatened with a boycott by the Nazis. Mann successfully sued both the theatre and also a Nazi-run newspaper.[11] Also in 1932 Mann had a role, alongside Therese Giehse, in the film Peter Voss, Thief of Millions.

In January 1933, Erika, Klaus and Therese Giehse founded a cabaret in Munich called Die Pfeffermühle, for which Erika wrote most of the material, much of which was anti-Fascist. The cabaret lasted two months before the Nazis forced it to close and Mann left Germany.[11] She was the last member of the Mann family to leave Germany after the Nazi regime was elected. She saved many of Thomas Mann's papers from their Munich home when she escaped to Zürich. In 1936, Die Pfeffermühle opened again in Zürich and became a rallying point for German exiles.

In 1935, it became apparent that the Nazis were intending to strip Mann of her German citizenship; her uncle, Heinrich Mann, was the first person to be stripped of German citizenship when the Nazis took office.[12] She asked Christopher Isherwood if he would marry her so she could become a British citizen. He declined but suggested she approach the gay poet W. H. Auden, who readily agreed to a marriage of convenience in 1935.[13] Mann and Auden never lived together but remained on good terms throughout their lives and were still married when Mann died; she left him a small bequest in her will.[14][15] In 1936, Auden introduced Therese Giehse, Mann's lover, to the writer John Hampson and they too married so that Giehse could leave Germany.[14] In 1937, Mann moved to New York, where Die Pfeffermühle (as The Peppermill) opened its doors again. There Erika Mann lived with Therese Giehse, her brother Klaus and Annemarie Schwarzenbach, amid a large group of artists in exile that included Kurt Weill, Ernst Toller and Sonia Sekula.

In 1938, Mann and Klaus reported on the Spanish Civil War, and her book School for Barbarians, a critique of Nazi Germany's educational system, was published.[13] The following year, they published Escape to Life, a book about famous German exiles.

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, Mann worked as a journalist in London, making radio broadcasts, in German, for the BBC throughout the Blitz and the Battle of Britain. After D-Day, she became a war correspondent attached to the Allied forces advancing across Europe. She reported from recent battlefields in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.[11] She entered Germany in June 1945 and was among the first Allied personnel to enter Aachen.

As soon as it was possible, she went to Munich to register a claim for the return of the Mann family home. When she arrived in Berlin on 3 July 1945, Mann was shocked at the level of destruction, describing the city as "a sea of devastation, shoreless and infinite".[11] She was equally angry at the complete lack of guilt displayed by some of the German civilians and officials that she met. During this period, as well as wearing an American uniform, Mann adopted an Anglo-American accent.

Mann attended the Nuremberg trial each day from the opening session, on 20 November 1945, until the court adjourned a month later for Christmas. She was present on 26 November when the first film evidence from an extermination camp was shown in the court room.[11] She interviewed the defense lawyers and ridiculed their arguments in her reports and made clear that she thought the court was indulging the behaviour of the defendants, in particular Hermann Göring.[10]

When the court adjourned for Christmas, Mann went to Zürich to spend time with her brother, Betty Knox and Therese Giehse. Mann's health was poor and on 1 January 1946, she collapsed and was hospitalised. Eventually, she was diagnosed with pleurisy. After a spell recovering at a spa in Arosa, Mann returned to Nuremberg in March 1946 to continue covering the war crimes trial.[11] In May 1946, Mann left Germany for California to help look after her father who was being treated for lung cancer.[13]

Later life

[edit]

From America, Mann continued to comment on and write about the situation in Germany. She considered it a scandal that Göring had managed to commit suicide and was furious at the slow pace of the denazification process. In particular, Mann objected to what she considered the lenient treatment of cultural figures, such as the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had stayed in Germany throughout the Nazi period.[16]

Her views on Russia and on the Berlin Airlift led to her being branded a Communist in America.[11] Both Klaus and Erika came under an FBI investigation into their political views and rumored homosexuality. In 1949, becoming increasingly depressed and disillusioned over postwar Germany's occupation, Klaus Mann died by suicide. This event devastated and enraged Erika Mann.[10] In 1952, due to the anti-communist red scare and the numerous accusations from the House Committee on Un-American Activities, the Mann family left the US and she moved back to Switzerland with her parents. She had begun to help her father with his writing and had become one of his closest confidantes. After the deaths of her father and her brother Klaus, Erika Mann became responsible for their works.

Mann died in Zürich on 27 August 1969 from a brain tumour[1] and is buried at Friedhof Kilchberg in Zürich, also the site of her parents' graves.[17][18] She was 63.

Biographical films

[edit]- Escape to Life: The Erika & Klaus Mann Story (2000)

Published works

[edit]- All the Way Round: A Light-hearted Travel Book (with Klaus Mann, 1929)

- The Book of the Riviera: Things You Won't Find in Baedekers (with Klaus Mann, 1931)

- School for Barbarians: Education Under the Nazis (1938)

- Escape to Life (1939)

- The Lights go Down (1940)

- The Other Germany (with Klaus Mann, 1940)

- A Gang of Ten (1942)

- The Last Year of Thomas Mann. A Revealing Memoir by His Daughter, Erika Mann (1958)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Erika Mann". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Frisch, Shelley (2000). "Mann, Erika Julia Hedwig : American National Biography Online - oi". oxfordindex.oup.com. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1601049. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Kontje, Todd (2015), Castle, Gregory (ed.), "Mann's Modernism", A History of the Modernist Novel, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 311–326, ISBN 978-1-107-03495-2, retrieved 25 August 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Thomas Mann/Heinrich Mann: Briefwechsel 1900–1949, S. 109

- ^ Thomas Mann: Tagebücher 1918–1921, Eintrag vom 10. März 1920

- ^ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Thomas Mann und die Seinen, S. 184

- ^ Golo Mann: Meine Schwester Erika. In Erika Mann, Briefe II, S. 241

- ^ Klaus Mann: Der Wendepunkt, S. 102

- ^ Colm Tóibín (6 November 2008). "I Could Sleep with All of Them". London Review of Books. 30 (21). Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Ruth M. Pettis (2005). "Mann, Erika (1905-1969)" (PDF). glbtq Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lara Feigel (2017). The Bitter Taste of Victory, Life, Love and Art in the Ruins of the Reich. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-4513-4.

- ^ Adam Lebor & Roger Boyles (2000). Surviving Hitler, Choices, Corruption and Compromise in the Third Reich. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-85811-8.

- ^ a b c Louis L Snyder (1976). Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. Marlowe & Co. ISBN 1569249172.

- ^ a b David Martin & Edward Mendelson (24 April 2014). "Why Auden Married". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ "WH Auden (1907-1973)". BBC History. 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Giles MacDonogh (2007). After the Reich - From the Liberation of Vienna to the Berlin Airlift. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6770-4.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 29738). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Craig R. Whitney (18 July 1993). "Thomas Mann's Daughter an Informer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Martin Mauthner: German Writers in French Exile, 1933-1940, Vallentine Mitchell, London, 2007, (ISBN 978 0 85303 540 4).

External links

[edit] Media related to Erika Mann at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Erika Mann at Wikimedia Commons